Oh I get it, it’s a sci-fi novel!

Alex Abramovich

The Strand Bookstore, which opened on Fourth Avenue in 1927, now takes up 55,000 square feet on Broadway and 12th and has ’18 miles of New, Used, Rare and Out of Print Books’ in stock. The novelist David Markson, who was born in Albany in 1927 and died in his West Village apartment last month, spent more than a few of his intervening hours at the Strand. (Here’s a short clip of him speaking there.) Still, it was a shock to walk into the Strand last week and find the contents of his personal library scattered among the stacks.

A shock, in part, because Markson’s work relied so heavily on other books: Schonberg’s Lives of the Great Composers (I paid $7. 50 for Markson’s copy), Wittgenstein’s correspondence (Paul Engelmann’s Letters from Wittgenstein with a Memoir, $12.50), Robert Graves’s edition of the Greek myths ($30 for the two-volume Penguin hardback). There are too many inscribed books for any one civilian to buy; most have notes, check marks, underlined passages. I’d guess that a few of them – especially the more heavily annotated ones – belong in a proper archive. And yet, here they are: hundreds of hardbacks (the only paperback I could find was a copy of Walter Abish’s How German is It?, sent to Markson with the author’s compliments), some of them with price tags covering Markson’s name, as if the buyers were afraid that his signature would somehow diminish their value.

I’d heard about the haul from Jeff Severs, who teaches at the University of British Columbia. He’d heard about it from a student who’d stumbled on Markson’s copy of Don DeLillo’s White Noise. ‘my copy of white noise apparently used to belong to david markson (who i had to look up),’ the student had written.

he wrote some notes in the margin: a check mark by some passages, ‘no’ by other, ‘bullshit’ or ‘ugh get to the point’ by others. i wanted to call him up and tell him his notes are funny, but then i realized he DIED A MONTH AGO. bummer.

‘That’s amazing,’ Jeff had replied. ‘Did he write his name in the front or something? Did you buy it secondhand recently – as in, his family sold off his library?’

yeah he wrote his name inside the front cover and the cashiers at the strand said they have his whole collection. favorite comments: ‘oh god the pomposity, the bullshit!’, ‘oh i get it, it’s a sci-fi novel!’ and ‘big deal’.

That night, I put $262.81 on the credit card and brought three shopping bags home to my fourth-floor walk-up: Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood($7.50), Yeats’s Essays and Introductions ($15), Leslie Fiedler’s Life and Death in the American Novel ($10), Tristram Shandy ($5); 27 books in all. My new collection includes old Modern Library editions (Joyce, Kafka, Balzac, Pater, Lao-tse and Tacitus), undergraduate philosophy texts (the future novelist paid more attention to Kant and Hume than to Erasmus, Descartes and Hegel) and Joyce’s Selected Letters (with brackets around the dirty bits). Thanks to Markson, I now own Stephen Joyce’sModern Library edition of Gogol’s Dead Souls. A gift? Did Markson borrow the book and fail return it? Or did he run across it himself on a visit to the Strand and wonder how it had ended up there?

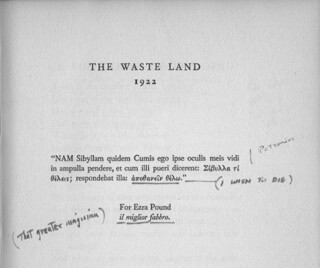

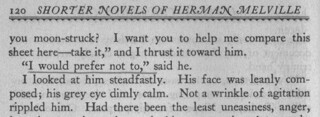

My friend Ethan paid not enough money for a heavily annotated edition of Hart Crane’s poetry, an even more heavily annotated T.S. Eliot, and a beautiful volume of Melville’s shorter works, with every one of Bartleby the Scrivener’s ‘I would prefer not to’s underlined. (‘Melville, late along, possessed no copies of his own books,’ Markson wrote in Vanishing Point.)

The next day, another friend emailed to say he’d spent $93 on Ellmann’s biography of Joyce, Pound’s letters to Joyce, Hardy’s poems, Spenser’s Poetical Works and A.J. Ayer’s Wittgenstein. ‘I found some Lowry,’ he wrote. ‘The letters and poems, but left those for someone who cares more about him than I do.’ Pound’s Cantos, Jan Kott’s Shakespeare Our Contemporary and Balzac’s Lost Illusions are all still in the stacks, at reasonable prices.

Comments

-

27 July 2010

at

12:47am

Justin RM

says:

I'm jealous, man. I think at this point the burden is on you to compile some of the more worthwhile marginal notes—horrifyingly lame pun intended—and share them with people like me. E-mail me some if you ever get the chance. I'd appreciate it. Seriously, it'd make my day.

-

27 July 2010

at

5:02am

Alex Abramovich

says:

Went back tonight, on my way to the local gigaplex, & got: Montaigne ($7.50), Camus' 'Rebel' ($7.50), a beautiful edition of Kierkegaard's 'Philosophical Fragments' (20 bucks), and Stephen Joyce's 'Don Quixote' ($7.50). The Balzac's gone, didn't check on the Pound, & Kott's still there (great book, btw). Also, lots of Bertrand Russel, Markson's 2-volume 'Don Quixote' ($25 bucks and worth it), and lots of other stuff.

-

27 July 2010

at

5:15am

Alex Abramovich

says:

As promised, 'White Noise' marginalia, continued:

-

27 July 2010

at

5:50am

Phil Connors

says:

Great piece, Alex: love his contrarian reading of White Noise! I once had the good fortune of meeting Markson in the basement of the Strand. When I recognized him and introduced myself, we had a good chuckle about a review of "This Is Not a Novel" I'd recently written for a New York paper, in which I'd attempted to mimic the style of the novel itself throughout. For a while thereafter we exchanged postcards, in one of which he admitted to "a leaky fissure in my cranium" that prevented him from writing anything overtly autobiographical. (I'd asked him for a contribution to a magazine I was editing. He politely demurred.) Were I within a hundred miles of the Strand, I'd be on my way to comb the stacks; as it is I'll content myself with the knowledge that a number of his books have fallen into good hands.

-

27 July 2010

at

9:01am

Jon Day

says:

I'll take the Jan Kott if it's still there!

-

27 July 2010

at

2:54pm

squattercity

says:

My own small Markson haul: http://grandhotelabyss.blogspot.com/2010/07/ex-libris.html

-

27 July 2010

at

3:51pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

Thanks, Squattercity. And thank you, Phil. Jon: What I'm thinking now is that the right thing to do is put Markson's library back together. A friend suggests that we start a Facebook group; that might be the way to go. Still, I'll drop by later and see if the Kott's there!

-

27 July 2010

at

3:57pm

adriana

says:

I'd really like to get that Montaigne off your hands.. Please let me know if we can arrange something.

-

27 July 2010

at

5:02pm

adriana

says:

@

adriana

I wrote my undergrad thesis on Montaigne. Reading Markson's marginalia would be a dream come true and I would treasure it always.

-

27 July 2010

at

6:34pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

@

adriana

Hi, Adriana. You'll find me on Facebook; give a shout....

-

27 July 2010

at

4:42pm

squattercity

says:

A noble proposal.

-

27 July 2010

at

10:34pm

A.J.P. Crown

says:

@

squattercity

Yes. Well done!

-

27 July 2010

at

5:22pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

First step: A Facebook group that you (and if you happen to have any of these books: you, especially!) are heartily encouraged to join:

-

27 July 2010

at

5:33pm

Jon Day

says:

Great idea, I wish you luck.

-

27 July 2010

at

8:04pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

Kevin Lincoln buys Markson's Gaddis, Roth:

-

27 July 2010

at

8:11pm

requiemapache

says:

The Strand's marginalia isn't always so satisfying, a Joseph Heller edition I bought there with $7.50 on the front cover also had the previous second hand store's price on the inside jacket - $5. Bastards.

-

27 July 2010

at

11:05pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

Indeed.

-

28 July 2010

at

9:47am

A.J.P. Crown

says:

Can't you call, say, the English dept up at Columbia, and get them to front you a couple of hundred dollars to pick up the rest? I'm sure they'd love to have them.

-

28 July 2010

at

10:11pm

squattercity

says:

@

A.J.P. Crown

According to one of the staffers at the Strand, our man bequeathed his books to the august booksellers row institution. And so reconstituting his library, particularly at an academic institution, would not be in tune with his chosen legacy.

-

29 July 2010

at

12:28pm

A.J.P. Crown

says:

@

squattercity

Thanks, that's exactly what we were wondering about. You guys need a Markson magnet.

-

29 July 2010

at

3:02am

Carland

says:

I had a chance to buy Markson's copy of Gaddis's JR a week or two ago, but I let it go. I knew someone else would want it more. But I did take home Markson's paperback copy of James Merrill's The Country of a Thousand Years of Peace. There are other poetry titles, including more Merrill, from Markson's library still on the shelves.

-

29 July 2010

at

12:48pm

Carland

says:

For man with such a strong relationship to the Strand, I bet Markson actually requested his library to end up there, and for it to be sold and scattered throughout the city and beyond. It wouldn't surprise me.

-

29 July 2010

at

6:42pm

Alex Abramovich

says:

Dear Carland,

-

30 July 2010

at

1:09am

Carland

says:

If Markson did bequeath his books to the Strand, he knew they would be divided and sold. He gave readings at the Strand and people have stories of seeing him wandering among the stacks; clearly, he loved the store. (It’d be interesting to find out whether or not the Strand paid the Markson estate for the books or if they were just donated to the store.) I think he meant for books to have a second (or third, or fourth) life, to be pulled off the shelves, taken home, and read again, and not to sit in a vault somewhere in the middle of Texas.

-

30 July 2010

at

2:03am

Carland

says:

Markson’s last four novels were, I think, his best. One of the veins that ran through those discontinuous and fragmentary books was the fear of death and the difficulties of relying on art for answers. It is almost as if sending his books to Strand was one last attempt by Markson to kick and rage against this fear. Like every entry or line from his later novels, each book from his personal collection is a fragment of his reading life. Dividing and selling his books is a sort of reverse-collage as each book finds new life in the hands or home of someone else.

-

30 July 2010

at

1:10pm

squattercity

says:

@

Carland

Dissolving his library in the pseudo-democracy of the Strand's shelves can be seen as Markson's final work.

-

30 July 2010

at

2:45am

Alex Abramovich

says:

Lord, the typos in that comment - apologies! I hope I got my meaning across.

-

30 July 2010

at

3:59pm

CSorrentino

says:

The conjuring of a vision of Markson’s library languishing “in a vault somewhere in the middle of Texas,” because (as Fred Bass put it) “what are they going to do with them?” is kind of breathtakingly hostile towards scholarship generally, and ultimately toward Markson’s reputation, because those dusty old scholars are going to have a lot to do with securing that (despite Carland’s belief that Markson’s work doesn’t lend itself to criticism). Now they’ve lost a tool. I don’t know what Markson’s wishes were, or, for that matter, what the wishes of his heirs were. Sure, they should be respected, but I don’t think “respect,” as a concept, is without bounds, and in any case a literary executor has a duty to preserve the author’s Nachlass. If what Markson felt toward his marginalia and interlinear remarks was indeed “indifference,” I don’t think that presents the strongest case for scattering them, certainly not one that trumps the historical, literary, and scholarly interest in them. Carland clearly intends the phrase in a pejorative sense, but it doesn’t seem like there’s anything inherently wrong with characterizing scholarship -- amateur or otherwise -- as “a treasure hunt through ephemera.” The problem obtains in the piecemeal way in which these remarks are trickling out. Take Markson’s comments on White Noise, repeatedly reproduced online. Are these the extent of his thinking on the book? Do they represent his attitude toward DeLillo generally? Is there another DeLillo novel in Markson’s collection -- The Names, for example, which might have held interest for the expatriate author of Going Down -- in which Markson revises or refines his opinion? Isn’t it of some inherent literary interest to know what one important post-war author thought of another?

-

31 July 2010

at

5:26am

Carland

says:

It appears that Markson or his estate wanted his library to be end up at the Strand. It’s not our place to question why. It’s none of our business. These books weren’t stolen and sold off to the highest bidder. In the last day or so, I’m reminded of one Markson’s narrators expressing disgust at the people who think they have some right to remove the last name on the tombstone of Sylvia Plath Hughes. Reuniting this library seems like a violation of one of Markson’s final personal, private wish.

-

31 July 2010

at

5:39am

Carland

says:

Several of Markson’s books appeared to be out of print and hard to find (like his edition Joyce letters with all those passages about dirty bloomers.) At the Strand, Markson’s out of print hardcover copy of The Recognitions sold for 9 dollars. Currently, a new Penguin paperback copy has a cover price of 25 dollars. Now, if you like hardcover books, and want to save money, Markson’s copy of The Recognitions (with or without marginalia) appears to have been a good deal.

-

31 July 2010

at

11:24pm

Annecy

says:

Hello everyone,

-

1 August 2010

at

5:29pm

squattercity

says:

Let's be honest: the fact that we're all talking about the books that were on Markson's shelves is fetishism, whether we're in the camp that wants to recreate the library or, by contrast, herald the individual sale of these volumes as a kind of after-death cloud-seeding of the dry lunar literary landscape. This over-involvement with the texts we presume he read (I admit, I bought six from the dollar carts) is romanticism in the extreme.

-

2 August 2010

at

9:24am

Phil Edwards

says:

@

squattercity

The first point isn't that odd. There's clearly room for debate about whether marking up [one's] books and scribbling in the margins is a destructive or creative act (see: this entire discussion). To fold back the pages so far that [one] would break the binding of a book is destructive; it damages the book as a physical object.

-

3 August 2010

at

2:07am

Carland

says:

@

Phil Edwards

Maybe his elementary school teacher didn't want the school library to be destroyed by 8 year olds.

-

4 August 2010

at

12:23am

squattercity

says:

@

Carland

Carsten: you're probably right.

-

4 August 2010

at

12:41am

squattercity

says:

@

squattercity

apologies for the typo, Carland

-

4 August 2010

at

12:23pm

Phil Edwards

says:

@

squattercity

Just making the point that there are two ways of looking at it. Personally I'm with you - particularly with regard to underlining (and especially wrt highlighter).

-

2 August 2010

at

11:38am

CSorrentino

says:

Setting aside -- forever, I hope -- any question of right and wrong regarding the disposal of Markson’s library; and not going anywhere near the enchantingly sentimental idea of his books flowing in a steady stream from the shelves of the Strand and through all the nooks and crannies of the city, directly into the hands of those who, congnoscenti and benighted alike, are united only by a pure and heartwarming love of reading (except to observe that it’s hard to imagine that many of the bibliophiles who’ve been combing the Strand for Markson’s books over the past week or so will not now turn around and sell those books as collectibles), that still leaves the academic question of the value of Markson’s library as a resource for studying his work, his life, his thinking. I don’t know if it’s a matter of “siding” with scholars; I don’t believe that scholarly interest exists in necessary opposition to the interests of artists, and I certainly don’t see how Markson (who, in addition to being a novelist and poet was also one of the first serious scholars of the work of Malcolm Lowry) would agree with this formulation. It seems beyond question that literary criticism will indeed play a role in consolidating Markson’s reputation, and it takes nothing from his achievement to acknowledge that. We read Herman Melville because of his books, but we were made aware of their importance through the efforts of Raymond Weaver, among others. Yes, Markson’s marginal notes and underlinings are certainly less significant than letters, diaries, drafts, etc. But that doesn’t mean that they are inherently insignificant, and I can't embrace the belief that there’s a kind of clearly-defined border beyond which there exist research materials suitable for “serious” scholarship and critical study, and before which everything is a mere “treasure hunt” for “fans.”

-

3 August 2010

at

4:32am

Carland

says:

I should have not said what I did about his books spreading throughout the city --that was just distracting: It appeared that the last wishes of a writer I admire were being ignored for the sake of a uncertain quantity of marginalia. I still see it as an attempt to close the barn door after the chimerical horses have bolted. People appeared to be bemoaning what they imagined they lost more than the actual man.

Read moreJeff Severs' student was kind enough to send some more 'White Noise' marginalia; pending her ok, I'll put it up in the comments tomorrow....

"This book may have set the all-time record for boredom. At 1/3 of the length, it might have worked."

"Awful awful awful"

"We got the point of this stuff a long time ago. A long time ago. It's now BORING! And has been."

"Are we supposed to believe this?"

"If this were not my first Delillo, I probably would have quit 100 pages ago."

"This 'ordinariness' is just that -- ordinary, i.e., a bore. Presumably it is meant as satire. Except, dammit, satire should be amusing!"

"Boring boring boring"

(and twice on one page) "Oh God"

http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=138148862885737

The dream, of course, is the get the physical books back together in one place, and make them available to everyone.

http://htmlgiant.com/author-spotlight/alas-david-finding-marksons-library-by-kevin-lincoln/

One last, sad trip to the Strand: Kott's gone. Ditto, Cervantes. Basically everything mentioned in print/comments, here & elsewhere, is gone. Still in the stacks: Lots of books on Joyce (including one by my old thesis adviser, Stanley Sultan), a few on Whitman, the four-volume Chicago UP edition of Greek tragedies (80 bucks!), Eliot's 'Cocktail Party.' Poetry anthologies. Etc. Nothing left on the $1 tables outside. I picked up an annotated edition of Eliot's essays. Twenty bucks. No inscription, but clearly his handwriting, w/heavy annotations to the essay on Baudelaire....

Apparently there are boxes of Marksoniana yet to be unpacked. Still on the shelves in philosophy, Josiah Royce, Karl Popper, G.E. Moore, and Benedetto Croce. On the dollar carts, I saw Vico's Autobiography and a commentary on Plato's Republic.

The word is out, though, and the faithful are trawling. Marksonism is alive in the stacks of the Strand.

I noticed that Markson rarely saved his dust jackets.

On a related note, a year ago I found Allen Ginsberg's paperback copy (inscribed with his P.O. address) of James Schuyler's Crystal Lithium. Also found at the Strand.

It is like scattering someone's ashes.

I hope more than a few of these books, like a book of poems, a novel by Balzac, or the letters of Van Gogh end up in the hands of honest readers, people who don't know who David Markson is, who bought one of Markson's books simply to read it. That excites me more than this effort to try and reunite the library.

From what I'm reading online, it seems that you're right - 50 boxes, w/50 books in each box. (And, contrary to what clerks at the Strand told me, some boxes haven't yet been unpacked.)

And yes - who can guess at motivation (let's say that you ARE right; maybe it was a romantic gesture; maybe it was born of bitterness, a sense of futility, etc.) - but Ethan and I wondered if that this might have been the case (though we didn't put it as nicely as you have). Still, I'm of two minds: on the one hand, it's pretty; scattered like ashes is just right. On the other, I wonder if it's the sort of bequest that (pace Max Brod) shouldn't have been ignored, or partially ignored, esp. given how important some of these books were to Markson's own. Some of the marginalia's funny. Some of it seems, to me, to be fairly important, if you happen to care about such things. Lots of it doesn't belong in an archive. But now we'll never know how much of it does, and how much literary scholars / critics / students / etc. have lost. I'm as romantic as the next guy, but this case, I'll take pedantry over the poetic gesture....

The parallels to Max Brod don't seem appropriate here. Brod was saving works of art. Markson's marginalia, if it's worth anything, is for the scholars, or, most likely, for his fans. Markson’s indifference to his own notes and sending his books away to be sold is not the same as Kafka’s anxieties about his own highly autobiographical writing.

Would what we learn by reuniting the library mean more than honoring the wishes of this writer we admire, love, or respect? As grateful as I am for Markson's work, and the dark comfort it provides, I don’t think it lends itself to scholarship. I'm paraphrasing, but he once said his approach to writing was "to see how little I can get away with." At best, combing through Markson’s notes looks to be a treasure hunt through ephemera, and only for the fans of Markson's writing. So Markson underlined Bartleby's every "I would prefer not to", and references to Gaddis shows up in other books, and he didn’t like White Noise --but what of it? How does this aid us in reading Markson’s books, a majority of which defy criticism? Owning a particular book that inspired a particular paragraph in another book is exciting, but its only value is as memorabilia, and limited to the current owner.

It seems to me the wish to somehow reunite these books --a labor of love, no doubt-- is more sentimental or romantic than my desire to honor a dead man's last will and testament. Many of us have a desire to be the next Max Brod or Malcolm Cowley, saving genius from oblivion, but the cultural responsibility here seems to be outweighed by respect.

I don’t know. When I imagine of all different people buying and reading a book from Markson’s library, I have the same haunting but bracing feeling I got after I finished one of his novels. It makes me shiver but smile.

I know you won’t do this, Alex, but take the Markson books that you already own and don’t plan on reading and sell them to other used bookstores in the city, like Mercer Books, East Village Books, or the new used bookstore at 66 Avenue A, or Atlantic Bookshop in Brooklyn.

And it’s crossed my mind that all the happy horseshit about Markson’s books “recirculating,” and enjoying “a second (or third, or fourth) life” is itself romantic and reifies the books as fetish objects to a far greater extent than the idea of preserving the library as a whole. Why do these books need to circulate? There isn’t any shortage of copies of the works of Herman Melville in the world. If the books have no worth as anything other than the content that was printed and bound within them, they might as well have been burnt, the ashes literally scattered.

So when it comes to scholars and artists, yes, most often I’ll side with the artists and art. I think Markson would too. Markson’s reputation is going to stand or fall on the merits of Markson’s work, not the work of scholars –especially if that reputation rests on marginalia.

This attempt to reunite his library isn’t like an attempt to save an author’s letters, diaries, rough drafts, or unpublished fiction or essays. This is mere marginalia --little notes, scribbled in passing, incomplete or passing thoughts of author and whatever mood possessed him when he was alone. Yes, it is exciting to see one author engaged with another author’s book, and to see how the writer’s mind works, but marginalia has to be one of the least reliable forms of writing a scholar could quote from with good faith. And so I can’t follow the belief “If only we had all his marginalia we’d know how Markson’s feelings about Don DeLillo have changed and evolved.” What if one day, back in 1997, a friend of Markson stole his copy of Mao II, which just happened to be full notes praising DeLillo and calling him a genius? What if there was a copy of Pafko at the Wall where on the last page Markson scrawled “I forgive Don everything”?

I’ll admit that Fred Blass and his Strand don’t feel like the best place for the books to end up --or even the best used bookstore in NYC --but Markson had a relationship with the store and it appears his wish was (to say nothing about his desire, perhaps, to help the Strand make a view thousand bucks) to see these novels, volumes of poetry and philosophy back in the hands of readers who’ll read them and treat them as books

I'm Annecy. I'm the proud new owner of Markson's copy of White Noise. I'm also not a very careful reader and rely too much on my memory.

Instead of "Oh I get it, it's a sci-fi novel!" it actually says, "I've finally solved this book, it's sci-fi!"

I'm very sorry! I hope this doesn't make people say, "See? Told you those books should've been at the Ransom Center."

So here are a couple of thoughts that are unrelated to the binary dilemma that seems to have gotten its grip on this thread:

--For a guy who told the audience at a 2007 reading at the 92nd St. Y that he had been taught in 3rd grade not to fold back the pages so far that he would break the binding of a book, it's odd that he seemed to have thought nothing of marking up his books and scribbling in the margins.

--For a writer who produced non-traditional novels, I'm amazed at how conservative his collection seems to have been. And also how exclusively focused on European art and thought it was.

--For a guy who clearly read widely and glanced around the room a lot, he seems not to have written--or at least not to have published--any criticism or essays (though perhaps he was following Wittgenstein from the Tractatus: Of what we cannot speak we must remain silent.)

Phil: I find marginal notes and underlining destructive but not creative. I have a hard time re-reading my old paperback of the 'Great Short Works' of Tolstoy and a messload of my philosophy books. They seem diminished by my haphazard use of the old Eberhard Faber No. 2. And I had to breathe through the pain when my girlfriend went through a paperback first-edition of 'Against Interpretation' (chipped, brittle and delicate, and purchased for $1 at the Strand) with a yellow hi-lighter.

A friend at college got heavily into mediaeval religious literature and bought his own copy of Julian of Norwich's Revelation of Divine Love. In those pre-Amazon days this was quite a big deal; it was only available as an academic hardback, which he had to order through a bookshop. I went round to his room once and found him reading it - "Oh, this is wonderful. Listen to this bit!" And he read out a paragraph to me, while simultaneously underlining it line by line in wiggly blue biro. I tried not to stare.

I’d like, though, to clarify the point I was trying to make about the marginal comments within Markson’s copy of White Noise, although I think Carland inadvertently makes the point for me when he(?) says that marginalia is “one of the least reliable forms of writing a scholar could quote from with good faith.” Yeah, well, I think if by “good faith” Carland means scholarly due diligence, which would consist of the scholarly endeavor of combing through Markson’s other DeLillo titles for marginalia, checking that against things he might have said about DeLillo in more guarded and public moments, etc., etc., that’s certainly true. Unfortunately, what’s sad is that those things didn’t happen. This doesn’t seem fair or right somehow. To atomize that library, and the remarks within it, is, in effect, to impose upon them the condition Carland describes, i.e., “little notes, scribbled in passing, incomplete or passing thoughts.” Yes, in their dispersed state I think that’s true. I don’t think it valorizes scholarship or enshrines the idea of gatekeeping to suggest that Markson’s remarks, archived, preserved, catalogued, and put in context, would serve both him and us better than the piecemeal release of “interesting” snippets to the world*. Since even within the genteel confines of the literary blogosphere the sensationalistic impulse prevails, the takeaway for people around the world, absent any illuminating context, has been the factoid “Markson hated DeLillo.” Carland doesn’t seem to think that the library united could have any effect on Markson’s reputation, and that may be -- but the library divided already has had an effect on it. Markson’s the snarky guy who hated DeLillo.

*especially, as Annecy makes plain in her very considerate clarification, when they are incorrectly transcribed.

WH Auden says, "The critical opinions of a writer should always be taken with a large grain of salt. For the most part, they are manifestations of his debate with himself as to what he should do next and what he should avoid."

And he was talking about written criticism or reviews, not notes made in the margins by someone halfway through a book.

While they appear to be the most sensational, those (mis-transcribed, though still playful) comments on DeLillo still might have surfaced in some article somewhere when the library had been saved. And that's the most many people would've heard of the marginalia, then the comments would've been forgotten in a few weeks. One wonders if the funny way in which Markson criticized Delillo actually brought him more readers than it did turn people off. But we're talking about a handful of people here. Either way,someone reading and enjoying his or her first Markson book a year from now isn't going to be affected by these quotes (ruined or not by atomization), especially since so many other snarky comments about other artists appear in works he actually had published.

It appears one argument for preserving his notes is that Markson is a lesser-known, or cult writer and his reputation apparently needs to be protected. For an experimental writer, he is pretty well-known, isn't he? His books are in print, his obituary was much larger than Melville's, he's discussed on the LRB blog, etc. More people should read Marson, certainly. But I don't think Markson's reputation is at a level where he needs a Raymond Weaver to save him. Maybe, someday it'll reach its nadir. (Unless it's already happened) Also, Markson's under-celebrated gifts aren't too out of proportion to the level of his renown to be considered scandalous. It seems more and more scholars and PhD students are looking to be someone's Raymond Weaver or Malcolm Cowley, regardless of their subject's talent or relevance --a sort of sycophancy mixed with the desire to be recognized as someone who understands and saves genius. I prefer people who just read books.