In 1993 the soothsayer John Major advised that fifty years hence Britain ‘will still be the country of long shadows on county grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs, dog lovers and pools fillers’. Still? That suggests these properties were extant in 1993. And maybe they were, somewhere. The optimist premier equated country with county, with his native patch, Surrey, where the past is never dead but constantly honoured in reproductions of varying degrees of happy bogusness. Surrey comes from a different time. It is, to appropriate Surreyspeak, forever a wholly unconvincing approximation of yore (1450-1600). It comes from a different place, too: so lavishly heathered, gorsed, pined, silver-birched and golf-coursed it might be North Britain. Yet despite this bonfire of the unities it is distinct, a monument to douce fakery, indeed the monument. It’s at its best when it is all dressed up, most real when it’s at its most sham self.

The architect and pamphleteer Thomas ‘Victorian’ Harris fretted about the 19th century’s inability to create an architecture peculiar to itself, its age, its engineering, its steam power and its myriad inventions, all the while failing to see that the architecture he craved was being made right in front of him. He couldn’t see it for its ubiquity. Here was the distinctive architecture of its time, derived from countless precedents, with cavalier inaccuracy and with unselfconscious abandon: Surrey’s domestic architecture. Furzy hills and sandy trails, which had earlier in the century been regarded with distaste by Cobbett (‘villainously ugly’), came to be embellished by ‘a crop of country houses … largely on new sites’. This was not, Ian Nairn insisted, ‘at all typical of the pattern in the rest of England’. You can, to quote his near double Tony Hancock, say that again, Mush.

Fifty years after Harris and a few years after the heyday of the Arts and Crafts movement, the battle of the styles was being refought, sort of. The protagonists were united in one bias: they loathed everything high-Victorian. The few who didn’t – the usual crew of Betjeman, Waugh, Lancaster, a Mitford or two and even Kenneth Clark – were regarded as frivolous self-advertisers playing at perversity. What had been a far from straightforward face-off between propagandists for diverse forms of classicism and, on the other side, god’s own warrior-goths, was exhumed as a multipartite squabble between bitching infants of all ages. There existed no stylistic hegemony.

Adherents of the many schools and schisms of modernism each believed their own school to be the one true faith. They weren’t alone in disparaging revivalism. The Architecture of the Modern Age would come from the past, but not the fusty old gothic past with its reek of incense. The Architecture of the Modern Age would come from simplifying Georgian precedents. That, apparently, didn’t count as revivalism. Nor did an appreciation of those precedents suppress an appetite for demolishing them. England lagged behind Europe and was slow to protect buildings made after 1714. Hence the loss, among many others, of Waterloo Bridge and the Adelphi. The destruction of the Adelphi was deemed ‘inevitable’ by the William Morris scholar John Drinkwater, as though to oppose it would be derisive of the common mood. Robert Byron, less precious than usual, regretted that ‘according to official and ecclesiastical standards … a bit of the old Roman wall is of more importance than Nash’s Regent Street, and one ruined pointed arch than all Wren’s churches put together.’ Little has changed. Antiquarian prejudice and ecclesiastical philistinism are in good shape, self-righteous as ever.

Gavin Stamp was not of the flock. He was a propagandist, a preservationist, a stern critic and fierce journalist. He was a great historian – evident in his Memorial to the Missing of the Somme (2006) – as well as a great architectural historian. No one else could have written Interwar. Unlike most historians, he has few scores to settle: he was the least small-minded of men. This last, huge, posthumously published work is a deflected portrait of the architecture of two decades when there was peace; unfinished at his death in 2017, it has been seamlessly completed by his widow, Rosemary Hill. In Interwar, Stamp is scrupulously equitable and veers towards a sort of stylistic indifferentism: everything engages him, even junk neo-Georgian buildings that are beyond meretricious. He celebrates variety, eccentricity and figures from oblivion who have seldom before been part of the cast of architectural-historical studies: he discovered, for instance, the fine perspectivist and occasional architect Raymond Myerscough Walker living in a vagabond caravan in a wood near Chichester, his archive stored in his car, a near sunken Rover. Such persons are much more than also-rans. They are the substance of a parallel history of Stamp’s creation that abjures inflated reputations, vapid self-promoters and the slimy gibberish of PRs and journalists who pump them up to this day. No names, no pack drill.

Modernism was coloured by collectivism, a thoroughly bourgeois collectivism that swiftly became conventional. The elision of architecture and Surrealism achieved by artists such as Carlo Mollino and Pancho Guedes was as suspect as Quality Street Regency, which wasn’t merely favoured by aristocratic fans of Rex Whistler but designed by them too: one of the most appealingly unusual houses mentioned in Interwar is the over-urned Templewood in Norfolk, ‘a grand Classical bungalow that was theatrical in character, not to say camp’. Pevsner agreed: ‘very pretty’. It was the work of Paul Paget and John Seely, Lord Mottistone. In spirit, if not detail, it is heir to Colen Campbell’s Ebberston Hall near Scarborough: sprightly and miles away from Office of Works Georgian, RAF Neo-Georgian, War Office Georgian.

Perhaps the Architecture of the Modern Age had already arrived. It was there for all to see in the Germany of the Weimar republic: glass and streamlining and, in the north, in Pomerania, along the Baltic shore, a mighty sculptural brick architecture derived from the cathedrals and warehouses of the Hansa. It was found in the Netherlands in the compelling futurism of Michel de Klerk. Had de Klerk not died in 1923 at the age of 39, architecture would have taken a different road. In England there were thefts from Viennese social housing in Liverpool and Leeds. There were excitingly sullen churches by Nugent Cachemaille-Day, a de Klerk without the gift for fantasy, who decided that his take on the great medieval cinema called Albi Cathedral needed northern grit and sleet. It was there in the less aggressive churches of F.X. Velarde and in Herbert Rowse’s ventilation shafts for the Mersey Tunnel, which could be the outward signs of a nocturnal scouse cult; and on the Isle of Wight, where the French Benedictine Dom Paul Bellot designed Quarr Abbey, rising above the Solent like a displaced Malian mosque; and at Battersea: Giles Gilbert Scott’s immense power station, fought over for decades, not least by Stamp, was one of the great tokens of its age. Its twin, downriver at Bankside, was, of course, also saved. The Guinness Brewery at Park Royal was vandalised by Diageo with the sanction of the late Tessa Jowell, a worthy precursor to the oikish Nadine Dorries.

These works were not of the Modern Movement. Yet they were modern and that was quite enough for a fulminating xenophobe with a heavy hand – Reginald Blomfield, destroyer of Regent Street. He railed against ‘modernismus … a vicious movement … I am prejudiced enough to detest cosmopolitanism.’ Blomfield wasn’t alone. If there was some enthusiasm for German buildings there was less for the people who designed those buildings and who would seek refuge in Britain. Siegfried Sassoon abhorred the organised social lie of Blomfield’s Menin Gate at Ypres:

‘Their name liveth for ever’ the Gateway claims

Was ever an immolation so belied

As these intolerably nameless names?

Well might the Dead who struggled in the slime

Rise and deride this sepulchre of crime.

When war is claimed as a mother of invention (A.J.P. Taylor, Paul Virilio), that invention is hardly intended to signify the memorials that constitute a quintessential building type of the 1920s, albeit not much of one. Although medals were fashioned of different metals according to the status of the award, men were buried alongside each other irrespective of rank and religion, which was something of an achievement in class-pocked Britain. Gerald Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, wrote in 1925: ‘It is melancholy to think that any village community should have rated the sacrifice of ardent young lives so low that it was held that their adequate commemoration was achieved by a cross of Cornish design and granite sold in various sizes by large department stores.’

There was no English or imperial tradition of monumental memorials, no exemplars such as von Klenze’s Walhalla high above the Danube. There was no Arc de Triomphe, no Lincoln Memorial. Calton Hill possesses a hallucinatory grandeur, but Scotland was not a model for the War Graves Commission; indeed, the Scottish National War Memorial is by Robert Lorimer and stubbornly eschews classicism in favour of a rough, craggy structure that suggests both the ecclesiastical and the bellicose. It might be taken for a folly. The conditions to be fulfilled by a memorial are not clear. How were the slaughtered to be described. The Glorious Dead? As Stamp puts it: ‘It was not necessarily glorious to be machine-gunned or bayoneted or blown to pieces or drowned in mud or burned alive or choked to death by poison gas.’ And G.K. Chesterton, unusually unimaginative: ‘A club, or hospital ward, or anything having its own practical purpose, policy and future, would not really be a war memorial at all; it would not be in practice a memory of the war.’ The Arts and Crafts architect William Lethaby disagreed: ‘The people asked for houses; we have given them stones.’ That, of course, is the way of the world. The Motherland Calls, the mighty sword-wielding figure on Mamayev Kurgan commemorating the heroes of Stalingrad, is magnificent. The surrounding bidonvilles for the unfortunate living and the thickly particulated Lada air they breathe are not. The planner Patrick Abercrombie wrote confidently that ‘modernist design sprang into being after the gap of the war.’

This improbable leap – architecture is a slow business – was countered by the sounder opinion of Paul Fussell: ‘It is a mistake to think that the Great War marked a caesura between traditional forms of expression and modernism.’ There was, rather, a continuum of architecture and sculpture. In 1931 Charles Reilly, sometime head of the Liverpool School of Architecture, published Representative British Architects of the Present Day, which, Stamp notes, ‘is representative of the period by being so very unrepresentative’. He ascribes the conspicuous absence of the proto-modernist Charles Holden to professional jealousy and observes that his cemetery at Passchendaele has an austere, military character similar to that of the contemporary South London Underground stations Holden designed for the Northern Line extension to Morden. Holden and Edwin Lutyens, who couldn’t be omitted, are the only specimens whose reputations have endured or been successfully exhumed. There was no aesthetic agreement among the other exhibits save a vague taste for forms of stodgy classicism, which, for all their literality, were approximate. Reilly’s subjects were uniformly hostile to modernism, while being hardly familiar with it. All that was known was that it was dangerously Bolshevik.

Dotard artists brought with them the tired idioms of long ago. They were Victorians encumbered with all the baggage of that era. They had done their best work before the first war and were no doubt grateful to be granted a further chance. Among them were, as well as Blomfield, H.V. Lanchester and Herbert Baker, remembered, if at all, as the subject of Lutyens’s gaunt jest ‘I met my Bakerloo.’ Despite their insularity and quasi-xenophobia some were adepts of Parisian Beaux-Arts. More usually their idioms were elephantine neo-baroque and ‘Wrennaissance’: it was in the 1910s and 1920s that the cult of Wren, ‘the greatest English architect’, now taken for granted, was fledged. The architect Harry Goodhart-Rendel was right: ‘Practically all Englishmen and practically no foreigners’ believe that Wren was a great architect. As if to prove it, the English dotards and their epigones would, amazingly, still be at it, all red brick and stone quoins, in the years after the second war. ‘Retardataire’ was a word Pevsner relished.

Reilly’s galère left out a number of artists of whose existence he may have been unaware, just as they may have been unaware of each other. Patrick Abercrombie mentioned some of them in the introduction to his Book of the Modern House (1939): ‘Mackintosh with his unrestrained fantasy in Glasgow; Edgar Wood with his flat roofs in Lancashire; Baillie Scott with his more determined return to folk art; Voysey with his own special originality – these men were outside the general trend; they were anathema in the Schools; but they set fire to Continental thought.’ They were a winterbourne which became a stream which swelled into a river.

Architects of a generation younger than those portrayed by the over-companiable, ultra-clubbable Reilly were responsible for new civic centres at Southampton, Swansea and Newport, Monmouthshire. They vaguely allude to Wren. They belong to the 1930s but give no sign that they were creations of the first aircraft age. Nor that they are public buildings for civvies. Rather they look back to some era of frugal militaristic functionalism that probably never existed. This Wrenish idiom reaches its apogee in the vast, ill-proportioned Royal Hospital School on the Shotley peninsula in Suffolk. Together with Nottingham’s Guildhall these works form a distinct group, generically ‘stripped classical’. They demonstrate that architecture is politically blind. The same forms are adopted by antithetical regimes.

Architecturally, the Arts Council’s eclectic Thirties exhibition at the Hayward in the winter of 1979-80 was a sort of lie, at best unthinkingly misleading. Nine pages of the catalogue are devoted to the Modern Movement, five are devoted to the rest, swept under the carpet and called a ‘spectrum of styles’. The atypical is misrepresented as the typical – an architectural-historical norm. The Modern Movement is invariably illustrated by the same few exquisite buildings because that’s all there were. There were no other examples. Choice was limited, it was a specialised taste shared by wealthy socialists and penguins and mocked by the gammon, not yet so called.

Gavin Stamp’s reaction was to rectify this silly deceit by editing an issue of Architectural Design that more accurately portrayed the 1930s. That issue contained the germ of Interwar. Stamp was correct: the Modern Movement was a fashion, just as the Greek Revival, neo-vernacular and neo-Georgianism, rogue gothic and all of Osbert Lancaster’s jokey taxonomies were fashions. Architecture is as pervious to fashion as hairdos, colours, gastronomy and drugs. The special pleading which claimed that the Modern Movement was more than just another style was spurious, though it didn’t appear so until that fashion gave way to the next: when its fairly brief span was unequivocally settled and its ‘sociological pretensions’ laid bare. It is an almost invariable tic of architects to pretend that their designs are determined by demands such as energy use, sustainability, wetland roofs, ‘friendliness’, permeability and warmth, when they are of course determined by aesthetic preference and profit. Architects imitate what they see, they are led by their eyes. This is demonstrated by the career of the versatile naturist Oliver Hill, a devotee of Lutyens whose work was notably varied. Hill would leap onto any passing caravan: Tudorish, streamlined, neo-Georgian, Vogue Regency, ‘pseudish’ (the last two are Lancaster’s whims). His leap was sure. Unlike filmmakers or playwrights, architects are often happy to stick to the same style indefinitely. Hill was unquestionably among the finest architects of the period yet he was treated with disdain by all camps because he neglected to belong to any of them. His clients thought otherwise. This tribalism coloured the writing of the time too. Apostates to modernism such as P. Morton Shand – sometime champion of German cinemas and grandfather of Queen Camilla the First – and J.M. Richards were, so to speak, blackballed by an increasingly polarised architectural press. Decades later Stamp would himself be on the receiving end of the same petty-minded antagonism. The notion of freedom of expression is never quite grasped in architectural circles.

‘Today we have got our Modern Architecture and very soon it will be absolutely inescapable,’ John Summerson could announce in 1941. ‘It has the loyalty of the young; it is established, with different degrees of firmness, in every school of architecture in the country. Soon it will not be Modern Architecture any longer. It will just be Architecture.’ For a man of such impeccable, if sometimes biddable, convictions he could not have been more wrong. Had he qualified his assertion with ‘in fifty years’ he might have been nearer the mark. He was also mistaken when he wrote four years earlier of the ‘fading influence’ of Stockholm City Hall, the most scrutinised building of the period. Summerson’s predictions proved to be no more than wishfulness founded in the conviction that the true source of architecture was Georgian. The 1951 Festival of Britain was to be hugely indebted to Scandinavia and Finland.

Optimism, always rash, could not have been more misplaced. The public proved to be obstinately reluctant. It became a commonplace that houses ‘looked like factories’. The avant-garde always has long years of derision and mockery to suffer before it is accepted, and even today, a century after modernism invaded, a dullard politician can still get a round of applause by sneering the words ‘modern architecture’ or ‘concrete monstrosity’. Those sneers are not directed at the popular amalgam born out of a collision between borrowings from Egypt, pre-Colombian America, the Ballets Russes, futurism, the trashier end of Cubism and the 1925 Paris Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs. The coinage ‘Art Deco’, possibly by the antiques dealer John Jesse (he couldn’t remember), wasn’t made until the 1960s. It was previously known as the Jazz Style and the Daily Mail style: the newspaper’s Ideal Home exhibition introduced the horizontally-banded Crittall window. It was gaudy, brash and carnivalesque and an offence against timid ‘good taste’, so it affronted both the Modern Movement’s propagandists and traditionalists, little Englanders and terminal Englanders (Lancaster again, and Betjeman and Pevsner, whose antipathies were more convergent than is claimed). Dazzling white walls, streamlining, vitrolite, green window frames, green pantiles (often blue in Bournemouth). Among its most satisfying examples – i.e. the gaudiest – were apartment blocks at Pinner, Muswell Hill, Smithfield, Highgate. They are the décor of film noir, of bias-cut dresses, co-respondent shoes, guns in pockets, Tatras and Bugattis and ‘fast’ lives, though not as fast as in America.

Here, too, piers excepted, was the first British architecture since the Regency to make accommodation with the sea (Brighton, Frinton) and with the pursuit of pleasure, one form of which was the cinema. Gaumont, Odeon, Regal: their names, Ian Jack wrote, ‘seemed independent of any history. They may have been intended to suggest luxury, romance, good birth and breeding.’ Cinemas and the arterial road factories of Hoover, Coty, Firestone were all façade, big sheds with a decorative face to the world. They were objects of puritanical bien pensant contempt. They were also among the earliest English buildings to show the influence of American billboard brashness, an autochthonous mode far distant from the European derived grandeur and pomposity of America’s 19th century and one which would choke the globe despite the proportionate efforts of amenity groups which loutish legislators have not listened to and never will.

Nairn might have amended ‘This was not at all typical of the pattern in the rest of England’ to include the rest of Europe. With the extension of railways into the wild, excursions in pursuit of the picturesque had become ever more popular. So had Claude glasses, a vital prop for framing a landscape. Stamp is clear that ‘neither the Picturesque tradition nor the romantic, nostalgic impulse in British architecture could easily be eradicated.’ Clough Williams-Ellis’s Portmeirion, which somehow escaped being tarred as kitsch, linked architects and writers of opposing tastes in delighted admiration, provided they didn’t look too closely.

As Andrew Saint has observed, among the first colonisers of the no longer distant Surrey hills were the painters Myles Birket Foster and James Hook. They were in the van of an easeled army. Charles O’Brien, the latest editor of the Surrey volume of The Buildings of England and an admirable successor to Nairn and Bridget Cherry, is on the money when he calls Witley a mini-Barbizon. Their houses, however, belonged to an earlier age. They remained generically high Victorian, mechanical, industrial, aggressive, not too concerned with aesthetic propriety. This idiom, the ultra-gothic or rogue gothic, would have been entirely unrecognisable to a revenant from the Middle Ages – he would be as astonished by the depleted though still sinister Foxwarren Park as we are today. It stole from every form of ‘authentic’ gothic, irrespective of era or place, and collaged the lot. It relished the consequent collisions of material, scale and idiom. It often aspired to be accretive and ostentatiously patched up – as, for instance, Aachen Cathedral really was. The fashions of the years piled up on each other, a palimpsest in the form of a quarry. It was contemptuous of prettiness let alone beauty. It said ‘Sod you’ as defiantly as the sculptural concrete of a century later. Birket Foster’s house The Hill, at Witley, was almost as scary as Farnborough Hill, an unrestrained anglo-normande monster a few miles away in Hampshire where the Empress Eugenie would spend her long widowhood in penumbral gloom.

Foster’s paintings though were infected by a soft-edged perpetual summer, which would soon manifest in a drowsy dreamy architectural revolution and provide a store of clichés for decades to come, decades during which Surrey’s domestic architecture would become celebrated around the world through magazines and books such as Das Englische Haus (1904). The newly suburban lanes often followed ancient cart tracks through rhododendron canyons. Their unplanned haphazard meandering afforded domestic privacy. This was the genesis of that Surrey speciality, the gated High Class Suburb (as Nairn, no ironist, called them): St George’s Hill, Wentworth, Camilla Lacey and so on. They would come in time to be valued by persons greedy for plastic columns: white collar criminals, oligarchs’ security apes, footballers, light entertainers and seedy golf pros – the improbable successors to the many yeoman farmers with modest acres who inhabited a county where big landlords and big estates were unusually few. Hence the proximity to each other of the new country houses built on plots hardly commensurate with their size. Nairn put it thus: ‘No firry hill but has an elephantine pile on or near it … it may be a specialised pleasure but at its best it is completely delightful.’ The conjunction of steep slopes, holloways, indeciduous trees, timber framing and timber mullioned windows, tile hanging and jetties formed an unprecedented amalgam – pseudo-bucolic enchantment.

All that was missing were the smocked children with hoops, the contented chickens, the jolly smiling woodsman with his adze, the beaming washerwoman, the geese gamely honking despite their unpromising future, the dog only too willing to haul his cart. They are scenery, the routine personae of Foster, Helen Allingham, Kate Greenaway and others. Their paintings told a lie, not entirely harmless, for they idealised rustic life at a time when, as John Ruskin had it, ‘We have blackened every leaf of English greenwood with ashes and our people die of cold.’ Even when they resisted the call of the chocolate box and broached realism, that realism was mitigated by comparison with French realism. Arthur Melville’s A Cabbage Garden is slight and ornamental beside Jean-François Millet’s L’Angélus or Bastien-Lepage’s studies of rural poverty and the squalor that accompanies it. John Brett’s Stonebreaker, which can’t resist including the inevitable cute puppy, is a staged tableau vivant. Courbet’s Les Casseurs de Pierres isn’t.

The smocked children with hoops sprang from kitsch canvases into a sort of life under the guidance of, inter alia, the Peasant Arts Guild and Peasant Arts Fellowship, whose propagandists, among them the painter and potter Godfrey Blount, railed against the usual targets: cities, mechanised agriculture, ‘materialism’, mass production. Blount championed folk music of questionable provenance played on ‘original’ instruments, ‘traditional’ dance, carving and chamfering handmade wooden toys at the John Ruskin School in Haslemere. He hailed ‘the dawning of nobler conceptions of the charm of labour and the unity of life’, which actually meant that you couldn’t move for looms, spinners and weavers and houses with names like Honeyhanger, Honey Hill, Stoatley Rough, Coneybury, Coneyhurst on the Hill. In south-west Surrey there prospered dozens of related associations bound by false memories of delving Adam and spinning Eve, a fervid enthusiasm for looking backwards and Luddism – which comes easy when you have electricity, gas and a motor home to protect the Napier and the Crossley. A peasant way of life demands a healthy income. Wentworth’s successors are not for the indigent: Blankenese in Hamburg, Roucas Blanc in Marseille, Aventino in Rome, Sintra outside Lisbon.

The most resolutely deep plunges into an aggressively quaint yesterday were those of Ernest Trobridge, with what Stamp calls his ‘licentiously free Tudor style’. Two of his Surrey houses, all waney wood and delinquent shiplap, have been demolished but his astonishing fortresses and exhilarating essays in rus in urbe remain in the north-west London suburb of Kingsbury. The splendidly monikered Blunden Shadbolt made elevated crazy cottages with the pre-loved remnants of demolished houses. His over-egged masterpiece, Smugglers’ Way, at Highcliffe on the edge of the New Forest (more pines, more sand, more fly agaric), was crassly sacrificed for road widening. It had three gables, two of them hipped, an eyebrow dormer like a lewd wink, thick thatch, an absence of straight lines and orthodox geometry, leaded lights and a quite exceptional abundance of ersatz beams and chimneys. Its improbable neighbour was Robert van ’t Hoff, a member of De Stijl and author of Lloyd Wright inspired villas near Utrecht, of Augustus John’s studio in Mallord Street SW3 and, after he’d eschewed modernism, of a retrophile Arts and Craftsism. Nairn, perhaps second-guessing Pevsner, senior partner in the first edition of Buildings of England: Surrey, omitted Shadbolt and Trobridge. Pevsner had a horror of kitsch and disliked expressionism, brutalism’s better-behaved precursor. Had Nairn allowed his own taste to determine that edition’s contents, a rather different work would have emerged. He often seemed to forget that he was writing a guidebook in an established series rather than a poetic polemic called Nairn’s Surrey.

Stamp revered Nairn just this side of idolatry, but avoided his hyperbole, lachrymose bursts of emotion and undue scorn. Rosemary Hill writes in her foreword to Interwar that ‘Gavin found Shadbolt funny, but he didn’t sneer at him, seeing in him one of the many ways in which architecture reflected the contrasts of the times.’ He also perceived a link between Trobridge’s roofs and the Amsterdam School’s crimper-thatch, like a perm turned to concrete.

Nairn’s efforts to distinguish himself from contemporary writers on architecture such as the embarrassing Reyner Banham were not entirely successful. He was trapped by the doxa of an era in which St Pancras’s shed was admired but Scott’s great Flemish hotel was under constant threat of demolition. He wrote of the fantastical Horsley Towers and its creator, the Earl of Lovelace: ‘It is sad that such an inventive engineering talent thought of architecture in the typical 19th-century way as something that was to be added onto structure, not to grow inevitably out of it.’ His qualified appreciation of Surrey’s supreme architect, Edwin Lutyens, in the early 1960s was conventional: ‘The genius and the charlatan were very close together’ – a formula that might be applied to countless artists. He admires the thrilling Tigborne Court but can’t resist left-handed faint praise. His characterisation of it as ‘feminine but not effeminate’ is puzzling going on meaningless. His declaration in Nairn’s London that ‘you want to give Sir Edwin’s precocious bottom a good clout’ is not meaningless: it belongs to the very order of silly giggly facetiae that he scorned in Lutyens.

Stamp, almost twenty years younger, wasn’t burdened by Nairn’s generation’s offhand dismissal of much of Lutyens’s oeuvre, which in the case of Alison Smithson mutated into stupidly inchoate hatred. Stamp was among those who rescued Lutyens’s reputation. Two generations of architect and architectural historian barely knew his name. Their familiarity with the work was restricted to the eye-catching Arts and Crafts houses for randlords and financiers, a new kind of country house that demanded a mere platoon of servants rather than a brigade. The epithet which is often attached to them, ‘dream houses’, has nothing to do with aspirational property acquisition and everything to do with oneiric retention. They are houses which might have come to him in dreams and which he would actually build – so rendering those dreams prospective. They have the limpid clarity of The History of Mr Polly and Tono-Bungay. (Wells’s choice of architect for Spade House at Sandgate was, however, Voysey.)

The fraternities centred on Haslemere were soon to suffer the usual fate of being sundered by minute divergences of ideology and aspiration. They endured till a few years after the First World War. The dissipation of the town’s ‘vegetarian atmosphere’ (Charles O’Brien’s noisome but most apt epithet) coincided with the more general dilution of Surrey’s architecture. Where Surrey led England followed and it followed a move – not a descent – into a less mannered mass-market Tudorbethan, a democratised Arts and Crafts and a rash of neo-Georgianism. The prolific Arts and Crafts designer F.W. Troup’s decision to leave Surrey to build Rampton Hospital was no doubt a sign of some sort of shift. Nonetheless, as Nairn noted sixty years ago, Haslemere remained ‘a little arty-and-crafty’. That was hardly an expression of approval. It is not much changed. One needn’t be familiar with its history to realise that it is anti-industrialism in built form, a vain protest in handmade brick. It was an exercise in collective Canutism that Nairn reckoned too twee by half.

According to Nairn:

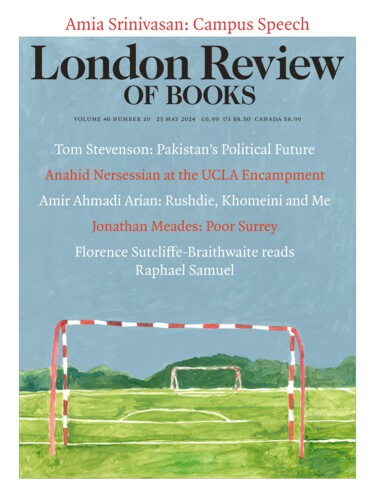

Poor Surrey was doubly unlucky after 1918. Not only did its architecture wither away but the type of house it had made world famous became in a dilute form the ideal of speculative house builders of the 1920s and 1930s … [and was] visited on the county by the thousand … by the 1960s [the style] seemed to have made the whole of it into a suburb.

A very particular kind of suburb, nevertheless, where you believe yourself to be in the country, albeit Thelwell country, pony and child bobbing above hedges till you come upon half a dozen triple-garaged paragons of good Queen Bessery or delicious Arts and Crafts fakery hiding, each in its personal thicket. And then bucolicism begins again. The fakery is harmless. It may even not be taken for fakery.

Stamp:

Suburban houses owed much to the designs for small and cheap cottages made decades earlier by Arts and Crafts architects like Baillie Scott, but a new, standard type had evolved from the typical gabled ‘Queen Anne’ urban terrace. Gone were the projecting back extensions characteristic of the terraced house; instead these houses were compactly planned, usually with the dining room next to the kitchen at the back (perhaps connected by a serving hatch) and three bedrooms upstairs.

The hatch, according to the bookseller Nigel Burwood, was a sign of social ascent to the lower rungs of the middle class.

Interwar raises in various ways – though always implicitly – the question ‘What is so invalid about sham?’ We admire follies, the ruins of castles that never were, a petrol station dressed up like a pagoda, eye-catchers, temples – so why not the semi? A suburban road (tan aggregate, no doubt) of lavishly bogus beamed houses does not summon up Fotheringhay, leper bells and scurvy. Rather it recalls the brief era, sure to end badly, of treasure hunts, demagogues, Ruth Etting and electric fires in the form of Scottish terriers. Stamp quotes Paul Oliver’s Dunroamin, a rare study of the suburban semi published in 1981, which pointed out ‘the cleverness of the composition of the standard semi-detached pair, in which elements like the hipped roofs and the two distinct bay windows “emphasised the separateness of the pair of semis”, while “other design features developed to display the importance of the individual house within the pair” – like the front doors being placed at the sides.’

Osbert Lancaster lamented ‘that so much ingenuity should have been wasted on streets and estates which will inevitably become the slums of the future’. Stamp, usually a fan, was unimpressed by Lancaster’s dissembled hope: ‘Far from being a slum, the suburban semi continues to perform its role as house and home, but few have acknowledged its success.’ John Major’s green suburbs may be tainted, the fodder of unfunny comedians and tired sitcoms, but they do remain invincible and decent. Indeed, Stamp asserts that ‘not only was Tudor the most popular and ubiquitous style in architecture between the wars, but the neo-Tudor suburban house, in all its many manifestations, constituted the first universal, generally accepted manner of building since the Georgian domestic style of the 18th century.’ In advertisements for products from mortgages to junk food it stands for homeliness, security and comfort, with the unambitious sunny perfection of Bayko, Minibrix and even Tudor Minibrix inflated to life-size.

The Georgian comparison is only perverse to a readership set in its old-fashioned Pevsnerian worldview, which is flawed by Pevsner’s being a progressive who feared progress: he wanted progress to stop with white orthogonal boxes. Stamp wasn’t perverse. He sees what is so obvious it is generally invisible. No one else would have dreamed of making this analogy. No one else would have delighted in such provocation though this was an expression of the observable rather than self-aggrandising épatage: he was not a smug contrarian. No one else would have had the chutzpah, for it implicitly links the hundreds of roads and avenues called Oak or Oakwood or Oakhill (350 in Greater London alone) to the umpteen grand streets and crescents called Brunswick, Montpelier, Coburg, Tivoli. It grants the roast beef aesthetic equivalence with the beau ideal of respectability. While the depth of bays and bows may differentiate, say, Southampton from Brighton, most terraces of the long Georgian age were flat-fronted, uniform and, thanks to mathematical tiles, untrue to materials. The semis of the 1930s strove for individuality. Essentially identical houses would be adorned with coloured glass, bays and timbers of varying patterns, a practice akin to the ‘badge engineering’ of cars in the 1960s and 1970s. It might further be argued that beyond décor the semi has the advantage in interior planning. The space in Georgian houses is crammed with killing stairs.

The densest accumulation of decorative beams and oriel windows are found in roadhouses, brewer-built ‘family friendly’ mega-pubs on trunk roads and in outer suburbs (the Grasshopper at Westerham and the Daylight Inn at Petts Wood are particularly frenetic in their woodwork). The highest concentration of them was in greater Birmingham, where Mitchells & Butlers vied with Ansells to attract customers with ever louder bars. They evidently encouraged drink-driving and are today hung with plastic banners offering gluts of fries. Their scale was palatial. The only domestic architecture which matched them were occasional outbreaks of black and white apartments. Hanger Hill Garden Estate in Ealing was puffed by Nairn: ‘A half-timbered square mile, and marvellous nonsense. Go and see!’ Stamp is drier, analytical: ‘The elements [are] used in such a way as not to pretend that they are ancient manor houses.’ He does not subscribe to the patronising barb, common among modernists, that the inhabitants of these buildings must kid themselves they are living in a distant age and write with quills.

As a method of fabricating, Arts and Crafts was worn out by 1914. But as a style it persisted as just another style – and Surrey is liberally sprinkled with it. The tenet of truth to materials – a sort of anthropomorphism which grants sentience to chalk and clunch – might be lost, but it had also been lost by the Modern Movement which, like the Regency, disguised brick with stucco. It crumbled and fell: in the 1950s Cheltenham looked as though it was suffering mange. More Arts and Crafts houses were built in the 1920s and 1930s than had been built in the movement’s heyday. Architects such as George Blair Imrie, Thomas Angell and George Crawley, were highly accomplished in moving redundant buildings from one site to another and supplying them with a minstrel gallery and a moat.

What Nairn considered architecture’s dissipation was not quite momentous enough to whet his appetite for melancholy. Rather, it fed his irked disappointment: he was tireless in his conviction that he had been let down, more by architects in whom he had invested hope during the postwar years of building restrictions than by planners. He’d doubtless have been browned off that O’Brien has cut the description of the former garrison church at Deepcut: ‘Corrugated iron kept in tip-top condition. It used to be painted red and orange, and looked exactly like a toy church.’ This was a site of Nairn’s Surrey boyhood. You want to shout ‘Stet!’, for O’Brien has dispensed with a rare expression of unaffected pre-architectural delight. But then he had to because the tin tabernacle has been repainted white.

Most amendments go in the opposite direction. Buildings of England: Surrey is greatly expanded. It seems twice the length of previous editions. The accumulation of detail is impressive. The great set-pieces Horsley Towers (Rhenish), Royal Holloway College (Loireish) and Claremont (Vanbrugh) are of course atypical, works of national importance that make no concession to Surrey: they might be found anywhere. The county’s richness has little to do with grandeur. Page after page records the sheer mass of the higher ordinariness, which is what makes Surrey extraordinary.

This distension is largely due to a catholic inclusiveness, to O’Brien’s long hours in archives as well as sedulous exploration in the field, which must be a guide writer’s nightmare given that so many houses are, like their occupants, in hiding and rather mysterious – an appropriate stage for Freeman Wills Crofts (who lived in the pleasantly spooky hamlet of Blackheath) and Francis Durbridge, laureate of rundown boatyards. It would take that sort of Surrey writer to explain why the monument to the first Lord Cobham shows him wearing what appear to be Louboutins.

‘Poor Surrey.’ The same lament is apt for the six decades since the publication of the first edition. O’Brien observes that the domestic works of Patrick Gwynne, Ernő Goldfinger and Michael Manser ‘are the absolute exceptions to the general tenor of housing’. He might have added Laurie Abbott and Richard Gilbert Scott. That tenor is relentlessly depressing. Today’s volume builders, patently less accomplished than those of the 1920s and 1930s, hoard and ‘land-bank’ plots. They take possession, spraying their demesnes like colonising feral cats. Their behaviour is sanctioned by the Tory Party, which they wholly own, and by timid, somnolent Labour. Then, when the moment is deemed propitious, they dump repetitive boxes on their territory. These boxes are intermittently relieved by junk ‘mansions’ for persons of immense wealth and risible taste: Updown Court in Windlesham really has to be seen – ‘luxury to the point of parody’, O’Brien writes. It belongs to the world of Hello! rather than the Architectural Review. But in its showy excess if not its style it is closer than might be acknowledged to the gargantuan minimalism of Norman Foster for McLaren and James Stirling’s unresolved shambles for Olivetti.

‘This generation of ostensibly flexible buildings,’ O’Brien writes, ‘achieved redundancy surprisingly quickly.’ Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’s fragrance factory at Tadworth lasted barely forty years: but that, today, is longevity. So much for ‘sustainability’, a mendacious nostrum so routinely spouted by the entire construction industry that it is meaningless. The demolition community enjoys an intimate relationship with the volume building community. It works so assiduously that no guide can keep up with it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.