‘Where do the noses go?’ Ingrid Bergman asks in For Whom the Bell Tolls, voicing apprehension over how to kiss. ‘Always I wonder where the noses will go.’ For an artist the equivalent might be ‘Where do the thumbs go?’ Hands are notoriously difficult to draw: all those fingers so close together, limblets so expressive when we use them in life, yet often numb and dumb when pictured. I remember the caricaturist Mark Boxer telling me that he felt ill-equipped to draw hands, so would frequently solve the problem by having his subjects stuff them into their pockets.

In Naples, probably in 1814, Ingres saw a fresco from Herculaneum of Hercules and his infant son Telephos. The Labourer stands in front of an enthroned figure who may be the goddess Arcadia, or, perhaps more plausibly, the Lydian queen Omphale, who enslaved Hercules for three years. Her right hand shows four digits: forefinger against her right temple, second finger against her cheek, third and fourth fingers bent inwards, thumb invisible. This hieratic gesture was transplanted, years later, into Ingres’s second portrait of Madame Moitessier, which took him twelve years of struggle and was finished in 1856. The pose suits the subject, who is presented as a high-bourgeois icon, static, imperious, worldly and more than a touch withdrawn. But three years later, when Ingres painted his second wife, Delphine, tender realism was the mode. Here, as with Madame Moitessier, the right forefinger is high on her cheek, while the second finger rests largely against the cheekbone, with the next two tightly parallel; but this time, here comes the thumb, its tip touching the end of her chin. The problem is that this gesture brings into play the meaty thenar eminence, that bulge at the base of the thumb, which all makes for quite a crowded fist distracting from the beloved’s face. When Ingres did a preliminary Study for Madame Moitessier Seated in 1846-48, the thumb was also present, and also a problem, seeming to shoot off in a weirdly different direction.

Mme Moitessier’s arms gave Ingres further aggravations. They were apparently ‘very plump’, and were initially painted as such; but Monsieur Moitessier (who made his money from importing Cuban cigars) judged such chubbiness inappropriate to his important wife, so Ingres slimmed them down. And later there were the critics. When Madame Moitessier arrived at the National Gallery in 1936 (a coup for its young director, Kenneth Clark), one critic protested: ‘Surely the little finger of a normal right hand should be articulated to a knucklebone and not drop from the off-side of the metacarpus.’ But as that early study shows, if you give the three remaining fingers their full presence, it makes for clutter. It was a question of line and sensuality rather than strict anatomy, so Ingres made them seem boneless. This wasn’t the only time he deliberately went against nature. The long, curving, erotic naked back of his Grande Odalisque of 1814 is achieved by adding vertebrae to her spinal column. Three was the number generally agreed on until 2004, when a medical examination of the painting concluded that Ingres had given her an additional five lumbar vertebrae.

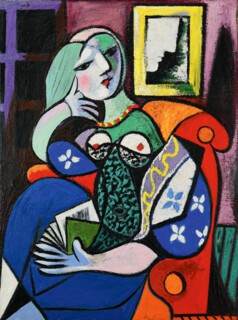

Anatomy was a less contentious matter by the time Picasso turned his young lover Marie-Thérèse Walter into the competitive homage Woman with a Book (1932). The gallery-goer had by now been trained to accept subjects with two noses and eyes in the back of the head. So Picasso calmly painted all four fingers of the left hand in exactly the same way – like the blades of garden shears – and the same length. When it comes to the right hand, things are a little less definitive. It looks as if the famous forefinger is high on the cheek, but beneath it is the second finger, bent at the first knuckle as if amputated, its stump pressing against the jawbone, followed by three more of equal size. So either this is a six-fingered woman hiding her thumb, or a five-fingered woman whose thumb (unlike the truly thumblike thumb of her left hand) is painted to look shear-like. But then Picasso’s portrait of his lover is about effect, not realism – as it was, if to a lesser extent, for Ingres.

The National Gallery, together with the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, has brought these two paintings together for the first time (until 9 October). The Ingres is hung on the left, the Picasso on the right. This is almost certainly the ‘correct’ positioning, given that it makes the two women’s bodies face each other. Their heads, however, are turned away to the right more or less in parallel. On the left, Mme Moitessier displays a sophisticated, salon knowingness. On the right, Marie-Thérèse Walter appears to turn away, pertly disdainful; with her cranberry nipples and cranberry lipstick, she seems to imply that she has all the sexual knowledge her earlier rival might secretly aspire to. And yet, hang them the opposite way round and you would get a contrary message. Picasso’s woman would be turning towards Mme Moitessier as if expecting approval, or at least comradeship across the centuries; while Mme Moitessier would be turning away from her, as if she knows just what Marie-Thérèse Walter’s game and intentions might be: she’s seen her sort before, thank you very much, and knows what ends such women come to.

Behind Madame Moitessier is a mirror, which allows us to examine her imperious profile. To some this raises a problem. One of the catalogue essays refers to ‘Madame Moitessier’s illogically angled reflection’. Another asks: ‘How could the sitter throw such a reflection at an acute angle onto the right side of a mirror that is directly behind her and, like her, perpendicular to the picture plane? It would seem to defy the rules of optics.’ There was similar concern about the ‘impossible’ reflections in Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère when it was first displayed – but Ingres had got there a quarter of a century earlier (and doubtless others preceded him). Why the fuss though? If Ingres introduced as many as five extra vertebrae into a woman’s back, and deliberately de-ossified fingers, why should we expect provable realism from one of his mirrors?

By the time Picasso came to deconstruct and reimagine Ingres’s painting, Cubism had dynamited perspective, so that Marie-Thérèse Walter and her surroundings could all exist more or less in the same plane; while Picasso himself, as Susan L. Siegfried puts it in her catalogue essay, had developed ‘a vanguard palette that unhitched colour from “natural” objects’. And he, too, gave particular attention to the mirror behind his seated reader. He turns it into a small vertical oblong with a bright yellow frame, which has its own ‘impossibilities’: Picasso has somehow brought the mirror not just level with Marie-Thérèse’s face, but even seems to have pulled it spatially in front of her. It becomes primary rather than secondary in the picture. Then there is the question of whose image is being reflected or displayed in it. It should be the sitter’s, but it might be an echo of the Roman-profiled Mme Moitessier herself; equally, and perhaps more convincingly, it might be that of the artist-lover himself, brooding possessively over the young woman who for years had been secreted away from the rest of his day-to-day life. If planes can dissolve and colours be unhitched, then the same can happen to meanings and identifications. The face in the mirror could refer to one of these three people or, oscillatingly, to all three at the same time.

The hanging of such pictures side by side is often presented as if they are ‘in conversation’ with each other across the years; in reality the conversation is one way. Picasso and Marie-Thérèse know all about Ingres and Mme Moitessier; but the latter are blind to and ignorant of the way they will be seen, interpreted, admired and patronised. The one-room exhibition, free in London, is already very popular, and rightly so, even if, when I was there, all the attention – and selfies – were focused on Picasso. Hardly surprising, of course, because Ingres is traditional gallery art, whereas Picasso is modern art. But there are 76 years between these two pictures; whereas ninety years separate Picasso’s painting and 2022. Picasso has also become traditional art in his own way.

‘Lesser artists borrow; great artists steal.’ Stravinsky may have said it first, but it is usually ascribed to Picasso. Steve Jobs, in a Channel 4 and PBS programme called Triumph of the Nerds, endorsed it thus: ‘I mean, Picasso had a saying … he said good artists copy, great artists steal. And we have always been shameless about stealing great ideas.’ The dictum has become a meme: you can even find online an aluminium sign bearing the original quote with the attribution ‘Picasso’ scratched out and replaced with ‘Banksy’. There are other contenders for authorship: Eliot, in his 1920 essay on Philip Massinger, has ‘Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.’ But in any case, it sounds just the sort of swaggery, competitive thing Picasso ought to have said first even if he didn’t. More important, though, is the statement true? In 1905, Ambroise Vollard exhibited a lithograph of Cézanne’s The Large Bathers in his shop window. Picasso bought a copy and took it home to examine and ‘steal’ its secrets. Two years later, Cézanne’s painting fed into Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Is this theft? Surely not; more a kind of accelerated homage. It would only be theft if Picasso had somehow managed to destroy Cézanne’s print and then passed off its discoveries as his own. And there is a great difference between the straightforward purloining of industrial or tech secrets from another company and the appropriation or absorption of one artist’s ideas by another. That original dictum, like many which overstrain for truth, could equally and plausibly be reversed. Lesser artists (lacking enough originality of their own) might be more inclined to surreptitiously steal, whereas greater artists, confident of their uniqueness, might be more inclined to borrow, openly and shamelessly.

The wider point is that great artists are, almost without exception, aware of and reliant on the great artists of the past. And often, the more famous they are, the more they live in haunted admiration of those they suspect might be even greater. Ingres, Delacroix and Velázquez all loured over Picasso. Bacon was so obsessed by Velázquez’s Pope Innocent that he was afraid ever to confront the original, while producing multiple interpretations of it. In a less threatened way, Hockney has depicted himself (naked) in a pally face-to-face with Picasso. Lucian Freud did versions of Watteau and Chardin. Howard Hodgkin was an exuberant hommagiste, with offerings to Degas, Corot, Morandi, Matisse, Samuel Palmer, Ellsworth Kelly, Vuillard and Seurat. Such conversations are nourishing, necessary and normal.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.