In 1975 David Bowie was in Los Angeles pretending to star in a film that wasn’t being made, adapted from a memoir he would never complete, to be called ‘The Return of the Thin White Duke’. This dubious pseudonymous character was first aired in an interview with Rolling Stone’s bumptious but canny young reporter Cameron Crowe; it soon became notorious. Crowe’s scene-setting picture of Bowie at home featured black candles and doodled ballpoint stars meant to ward off evil influences. Bowie revealed an enthusiasm for Aleister Crowley’s system of ceremonial magick that seemed to go beyond the standard, kitschy rock star flirtation with the ‘dark side’ into a genuine research project. He talked about drugs: ‘short flirtations with smack and things’, but given the choice he preferred a Grand Prix of the fastest, whitest drugs available. He brushed aside compatriots/competitors like Elton John and called Mick Jagger the ‘sort of harmless bourgeois kind of evil one can accept with a shrug’. If pushed, this apprentice warlock could also recite Derek and Clive’s ‘The Worst Job I Ever Had’ by heart and generally came on like a twisted forcefield of ego, will and fantastic put-on.

It’s impossible to imagine someone like Bowie giving the media anything like this kind of insane access today – but then, of course, there is no one like Bowie today. In 2016 it might take five months of negotiation to get an interview with the superstar of your choice and then you’d probably have to present your questions in advance and be babysat by three or four PR flaks and a spooky zombie-faced entourage for the whole blessed 15 minutes. In 1975, Bowie just turned up grinning, already babbling, at Crowe’s door. When Crowe got him to sit still long enough he couldn’t stop talking, which may or may not have had something to do with the industrial amounts of pharmaceutical cocaine he was daily ingesting. He had become almost an abstraction in the dry California air: surrounded by stubbly country-rock cowboys and wailing witchy women he was a sheet of virgin foolscap. Where did he fall from, this Englishman with his barking seal laugh and outrageous quotes about Himmler and semen storage and articulate ghosts?

Station to Station, which Bowie released in January 1976, came complete with glancing references to the esoteric teachings of Kabbalah (‘Here we are: one magical movement, from Kether to Malkuth’) and Crowley’s obscure (but unobscurely sexual) poetry collection of 1898, White Stains. (‘Kether to Malkuth’ represents the A to Z, so to speak, of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, which Bowie can be seen drawing in outtakes from a photoshoot included on the 1999 CD reissue of Station to Station.) The album was just under forty minutes long, with three songs per side and a subtle, striking, modernist sleeve – white space, black sound baffles and a red tickertape of words along the top. Red, white and black, a colour chart of his alleged diet at the time: cocaine and milk, raw red peppers and the printed word. In later years, Bowie hinted that Station to Station was some kind of codified ceremony drawn in sound (‘It’s the nearest album to a magical treatise that I’ve written’). Truth be told, you could go as mad as a pampered rock star trying to sieve and parse all the album’s different references and clues. It’s quite a witty record, in its skeletal way: after all, what could be less mid-1970s USA than a Thin White Duke with his Gauloises and artsy 19th-century references, cold white spotlights and muggy Berlin atmospheres? It’s about as far from Kiss and Led Zeppelin and the Eagles as you could possibly get.

Station to Station is both decadent and symmetrical: one side ends with ‘Word on a Wing’, the other with ‘Wild Is the Wind’. These two tracks, those unfurled wings, were completely different from anything he had previously recorded, from what any rock star has ever recorded (except perhaps Scott Walker, a Bowie household god from way back): spare, hauntingly personal and as close to simple and emotionally direct as he would ever let himself get. In his age of grand illusion he returned to stately melodies and simple words. ‘Word on a Wing’ is the song as protection, a counter-spell for a white-knuckle time, almost classic soul/gospel with its ‘you’ alternating between earthbound lover and timeless Christ. ‘Wild Is the Wind’, originally sung by Johnny Mathis for a 1957 Hollywood potboiler (and given perhaps its definitive performance by Nina Simone), is like a sung doppelgänger, and even here (with someone else’s lyrics) there were hints of matters ethereal: ‘For we’re like creatures/of the wind.’

No matter what your feeling about David Bowie and his work – whether you like all of it, or only love bits of it, or are determined to collect every last thing – it was impossible for his death last January not to feel like some kind of marker. The 20th century was the age of the frontline news photo, the water-cooler TV moment, the must-have LP, but all those heat-of-the-moment things have been demoted or disappeared in our new century’s digital realignment. In our current post-everything age, Bowie’s death was another reminder of how times have changed: an oldtime star who once enacted his alter ego Ziggy Stardust’s demise as an old-fashioned diva-esque theatrical goodbye-ee, and who more or less staged his own death online, with admirable restraint, impeccable good manners, and a profoundly surprising, legacy-salvaging last work, Blackstar. His career began in the early-to-mid 1960s when rock music itself had barely got up a head of steam, BBC2 had just become the UK’s third TV channel, and there was very little ‘media’ to register the underground tremors of rock. By the time he died, the music and the culture it gave birth to had boomed, then bust. There is still music and obscene amounts of money to be made – perhaps more than ever. But it sometimes all feels like little more than a Potemkin masquerade, mass nostalgia for a time when rock really mattered. It’s impossible to imagine something like Bowie’s masterpiece Low (1977) coming out now, an album split down the middle like an old Mad centrepiece, one half fidgety pop songs (the whitest blues ever recorded), the other just pure tone.

What is there left to know about David Bowie? What is there left to unearth? I’m really only half a Bowie fan and I already had a whole separate shelf for Bowie books, even before the posthumous publication tsunami. One thing you can’t help but notice about the new books is that the dominant tone has changed. Even at their most celebratory, they are far more wistful: this is pop culture eschatology. The authors seem haunted by the past, with little or no sense of what a post-Bowie or post-rock future might hold. There’s a feeling that nothing will ever be as surprising or shocking again; that rock as ‘alternative’ culture is done, and only remains to be archived and periodically dusted. The implication of at least two of the new titles is that we’re living in times shaped by some kind of Bowie/Glam legacy. I don’t quite see it myself, partly because of a long-ingrained distrust of words like ‘epoch’, ‘era’, ‘age’ and ‘legacy’, which make me feel as if things are being divided up too soon, too neatly, and for convenience’s sake. Maybe even for the sake of some convenient branding. Just look at these four new books: three of them have an identical Aladdin Sane flash on the cover, and two have the same bloody title, which strikes me as pretty good evidence we’ve reached peak something or other. There are more and more books like this these days: rock histories and encyclopedias, stuffed with information, compendiums of every last detail from this or that year, era, genre, artist – time pinned down, with absolutely no anxiety of influence. And while it would be churlish to deny there is often a huge amount of valuable stuff in them, I do think we need to question how seriously we want to take certain lives and kinds of art – and how we take them seriously without self-referencing the life out of them, without deadening the very things that constitute their once bright, now frazzled eros and ethos. One of the big differences between Bowie’s heyday in the 1970s and now is that today you can choose from a huge selection of books on any given cult figure (Nick Drake, Gram Parsons, Syd Barrett etc). In the days when such figures were active you had to be satisfied with an occasional music-press annual, or the lyrics printed in your girlfriend’s Jackie, or, if you were really lucky, a title like The Sociology of Riff (no photos or illustrations). Maybe one of the reasons the 1970s were such an incredibly creative time is that we weren’t all reading biographies and blogs and tweets about (or even by) our heroes, who in turn weren’t thinking about the best way to ‘grow their brand’ exponentially through a social media arc. All that unmediated space waiting to be filled!

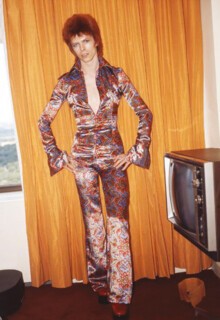

Bowie in Los Angeles was a kind of mantic probe for young kids discovering the joy of sex, sexuality, art, artiness. He was going into areas that no one had really explored before. He left spaces for his followers: not just the hierarchy of stardom and fandom but a strange, astute, uncanny folding of one into the other. From album to album there was a strange, light, almost mocking dialectic: he taught us to be critics of our own enthusiasms. He was ‘post’ and ‘meta’ and playfully ‘iconic’, before such terms had any real popular currency. July 1972: blue guitar, red boots, jumpsuit made of cushion covers from a bad mescaline trip, orange hair, a Klieg-light nimbus around his ghost-train head. A big crooked grin like he’s having the best possible time, like he has just sold the waiting world a truly irresponsible dare, his arm curling around the guitarist Mick Ronson. ‘But he thinks he’d blow our minds!’ And he did. One reason for that blown fuse was that Bowie had already worked out that the best way to put across a serious point was to stage it as an almost luridly OTT showbiz scene. You have to remember that Top of The Pops was it. There was no pop media at large, only three channels: everyone in the country was eating their tea and watching the same flicker of sound and vision. And here was this flirtatious pop-art revelation, all under the disbelieving eyes of everyone’s parents: a cosy family teatime – then wham bang! Did you see that! What on earth was going on there? Then he was gone. There was no rewinding to playback and OMG on Twitter and sharing it on YouTube the next day.

The first girlfriend I ever had, circa mid-1970s, worked a Saturday job at the make-up counter in our local Boots; I worked at H. Samuel, the high-street jewellers. These were very Glam jobs, which is to say not at all glamorous, but rather make-do glam, British glam. With Glam you could always see the joins, the stitching, the wig glue. Whoever it was that said the Sweet looked like ‘brickies in make-up’ got it exactly right: a profusion of perms, verdant chest hair and vertical-lift-off sideburns. But Bowie was something else. Bowie did look good, even when what he was wearing was as silly as what everyone else was wearing. Beyond good in fact, otherworldly: his make-up was not merely heavy-handed appliqué, it was a masquerade with echoes of times gone by, and maybe some unimaginable future. How much Bowie was really Glam at all is surely up for debate. His aspirations were always different: he was always headed in some unreadably different direction. Even before Glam, if it was different he’d tried it. Before he had a proper audience, he rifled the cultural event horizon like a pack of Tarot cards: he was beatnik, mod, mime, novelty record maker, hippy, arts lab founder, would-be ambisexual proselytiser. (He even dreamed of staging a proto-Ziggy sci-fi musical, but was stymied by, among other things, how to conjure up a ‘black hole’ convincingly on stage.)

One of the reasons I’m glad Simon Reynolds gives so much space to this earlier period (in his outsize but periodically acute history of Glam) is that it furnishes real clues to later Bowie, the Bowie of superstar myth, the master manipulator, one move ahead of everyone else. In his 1975 Rolling Stone interview Bowie remembered being a ‘trendy mod … a sort of throwback to the Beat period in my early thinking’. But it’s easily forgotten that amid all the Genet references, Mingus namedrops and mime moves, the likes of Bolan, Bowie and Bryan Ferry were very much in love with, and shaped by, mainstream British showbiz and Saturday night TV. Recall: Lulu singing ‘The Man Who Sold the World’. Recall: Bryan Ferry duetting with Cilla (‘and special guests Gerald Harper and Tony Blackburn!’). Recall: a newly shorn Bowie guest-starring on Bolan’s camp-for-kids teatime show, Marc. This was what made them who they were: they could play in both keys, MOR versions of avant-garde modernity. People still get into knots about the ‘mystery’ of Bowie’s serial life-swapping in the 1970s, but he’d been pulling the same trick for years on the perimeter of Tin Pan Alley before he applied it to rock. A bit of sci-fi, a bit of up-in-the-air sexuality, a bit of scarves-in-the-air sing-along, a bit of an ‘Oh no he isn’t!’ panto vibe, and a lot of power chords. Surely one of the main reasons we project other, more fancy motivations onto the blank screen of Bowie’s waiting face is precisely because of its breathtaking and deeply odd beauty. If he’d looked more like John Bonham we might not be having this conversation.

Bowie had a striking talent for shaping luck or forcing serendipity, and for finding the right other half in the right place at the right time: early manager Kenneth Pitt, producer Tony Visconti, personal assistant Corinne Schwab, and even (or especially) his first wife, Angela Barnett. (You could write a whole piece about Angie’s polarising effect on people and the question of how much she contributed to his breakthrough in the 1970s. As someone who had to read every last page of her bafflingly awful 1993 memoir, Backstage Passes, I find it hard to dredge up any feeling of protective support, but it’s hard to believe she had as little to do with her husband’s canny self-reinvention as some fans would have us believe.) Another key to his success in the 1970s was that his rock superstar personae, including Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, were both otherworldly and inclusive, up on a pedestal and down in the everyday dirt. ‘You’re not alone!’ Bowie sings: ‘Give me your hands!’ Here was someone who looked like a star but managed to communicate something like a fan’s own baffled awe. It was as if he was saying: ‘Just look at all this stuff we suddenly have to play with in rock and roll! We’re the first, too! Isn’t it a gas?’ It’s very hard with a lot of his songs from the early 1970s to tell how far Bowie’s tongue is lodged in his cheek; maybe he didn’t know himself. A lot of his more ‘surreal’ lyrics of this time are more Goon Show than Velvet Underground. ‘Hazy cosmic jive’ indeed. A song like ‘Space Oddity’ teeters right on the edge of ridiculous overload: one minute it’s sensitive, free-festival acoustic guitar, the next vibrating handclaps and space FX. Let’s throw in every trend of the moment: space travel! stylophones! existentialist gloom! He was part hippy, part beady-eyed nitroglycerin queen, part Penguin Modern Classic reader, part theatre door Johnny; or, as the American critic Robert Christgau once put it, ‘a middlebrow fascinated by the power of a highbrow-lowbrow form’.

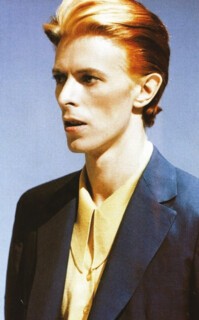

Bowie between two poles: laughter-madness-performance v. cool calculation, media plotting. On one hand, the nerveless psychological chess player, three moves ahead of everyone else; on the other, a man haunted by the whole troubled (and unresolved) matter of his older half-brother, Terry Burns. It was Terry who had introduced the young David Jones to Buddhism, Beat poetry, Mingus, and who later slipped or snapped into genuine psychosis, to lead a cruel jacitation of a life until his eventual suicide in 1985. Bowie himself played with and performed a version of madness far nearer a late 19th-century Euro-romantic (and very painterly) notion of things. An idea of ‘Europe’ haunts his work, and may even be what steered him back from the precipice of genuine black-out or white-out in the late 1970s. It can hardly be a coincidence that after leaving the coast of California on a jet plane he ended up behind a wall, in shadowy Berlin. In the sun, he plummets. In the shadows, he blooms. And with a double! Bowie had brought along Jim Osterberg, aka Iggy Pop, the none-more-messed-up singer of the apocalyptic heavy rock band the Stooges, whose career rejuvenation Bowie had made a point of honour. Aversion therapy: you can’t say no to beauty and the beast. The sleeves for both Heroes and The Idiot took their cue from the work of the German painter Erich Heckel, a source Bowie would return to later. This was not the genuine disturbance and real ‘madness’ of Syd Barrett, say, which would have been all too unromantic, mere daily drudge, a matter of counting the same sequence of numbers over and over again until death.

A scientific researcher with no emotional investment in Bowie could conduct an empirical study of his interviews down the years and record two main traits. One: where the choice was either a fascinating lie or a disappointing truth, Bowie would always go for the former. Two: he had an almost pathological need to be liked. It is possible that for Bowie, being liked was even more important than being taken seriously. He was always a skilled and guilt-free liar. The very first time he appeared on screen, I believe, was on a 1964 BBC teatime ‘novelty’ news item, where he posed as an earnestly disgruntled spokesman for the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Long-Haired Men. (He actually had more of a straggly, shiny bob than a long, hippyish hairstyle.) Apparently the Spokesman thing was entirely off the cuff. The 17-year-old Bowie could do something like that as naturally as breathing: he opened his toothy English mouth and out came the tallest of tales. Everyone was happy: aspirant pop star, TV crew, teatime audience, maybe even a few light-hearted longhairs.

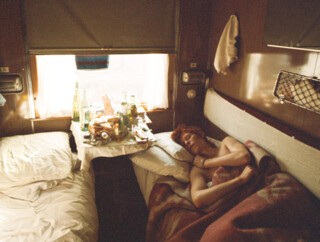

I don’t think it’s unfair to say that as an artist, writer, actor, singer, Bowie was good, often very good, but could never join the ranks of the greats in any of those areas. What he was great at was being David Bowie – the only one we ever got, or will ever have. The huge surge of affection when he died came about partly because people felt that no matter how far away he travelled, he remained in some indefinable sense close to them, one of our own – a working-class kid who never forgot where he was from. I’m not entirely sure about that. Part of me thinks that Bowie saw through ‘class’ at a very early stage, and realised that a large percentage of it was just another kind of performance. After the bacofoil pyre of Ziggy was he ever really ‘English’ again? Wasn’t he rather our brightest exile? The amount of non-professional time this quintessential London boy spent in the UK after the early 1970s is minuscule. There are snapshots of him in the American desert, Arizona, Los Angeles, Berlin, Tokyo, New York; at a loose end in Switzerland; asleep on a European train idling between stations; gone to ground in Berlin (in the kind of district he would never have considered a base in the UK); finally at rest, an art-collecting, thought-collecting Englishman in New York. Naturally, he made obligatory visits to London clubs when something exciting was happening, but most of the images of him in the UK that flash to mind are rather unfortunate: the disputed ‘wave/heil’ at Victoria Station from the back of a Mercedes in 1976; or down on his knees solemnly reciting the Lord’s Prayer at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert in 1992; or as a smart-alec cameo in Ricky Gervais’s smug TV self-com, Extras. For long periods of time he was all over the place, homeless and disjointed and – perhaps – happy that way. One of my favourite photos, by Geoff MacCormack, shows Bowie asleep on a train, between stations, Vladivostok to Moscow, in 1973. It may be one of the only portraits we have where he is entirely at rest – mouth shut, eyes closed, no public gaze to contend with, no hunger in other people’s eyes, no need to scan the room or prepare an opening gag. The last cigarette of the day smoked, the last sentence in the latest book underlined, make-up sluiced away, dreaming like the rest of us of something ridiculous and sublime.

Bowie sometimes seems to have regarded sound itself as a subset of space, a succession of planes, crypts or topoi where he could hide or advertise, measure or medicate, celebrate or mourn himself. A sense of simultaneous projection/encryption is at the heart of his best work: the idea of a ‘split’ personality embraced as healthy, even helpful; whiteness and blackness, authentic and plastic, real and ersatz, dark and light – mere categories, useful dance steps, not unbreakable truths. This doubling effect is to the fore in ‘Fame’, the final track on Young Americans (1975), which is both genuinely tin-tack arched-back funky as can be, but also so sealed-off, hygienic and airless that it erases any trace or taint of genuine metabolic heat. You can imagine that druggy riff going on for a thousand years, until the end of time. (I clicked on Google for the song’s lyrics and one site I saw just had the word ‘fame’ repeated 19 times, which is kind of on the money.) It’s such a hard, clipped, merciless sound; but the words, too: ‘reject’, ‘flame’, ‘insane’, ‘bully’, ‘chilly’, ‘hollow’. Compare this with the flowery songs he was writing only a handful of years before. I always half-imagined he was singing ‘Fame’ from the back of the limo he mentions – a ‘dream car twenty foot long’ (as he put it in the song that ‘Fame’ could be said to be twinned with, Station to Station’s ‘Golden Years’). Or, if not singing, repeating the words in his head as a nursery rhyme to keep his overstimulated skull from cracking open. A fissure that would let all the false, neon light into a cosy darkness. He finally had everything he’d worked for, for so many years, and what did he do? Ran for the shadows, where he got out his copy of Crowley’s Magick in Theory and Practice to work some not-joking spells in order to facilitate … what exactly? What deeper or stranger form of elsewhere or otherwise could he possibly have desired?

Deep in my dreams is an unmade movie: something like Fassbinder’s Despair crossed with Laurence Harvey in A Dandy in Aspic, starring Scott Walker and Bowie as Cold War agents trailing one another in a wilderness/wonderland of dark two-way mirrors. After all, Bowie was a man whose way of keeping his most vital secrets close to his chest was to gab away at ten to the dozen at the drop of a fedora, giving every last interviewer (interrogator, partner, label boss) the appearance of off-guard disclosure. The spy operating on remote control is a close relative of the undead, a nine-to-five vampire (nine at night until five in the morning), and it’s easy to see Bowie’s music-making of the mid-1970s as a form of spycraft: assuming identities, exploiting new gadgetry, eavesdropping on himself. Trans-Europe Express, with the emphasis very much on trans. But there is also an unmistakable mood of mourning and melancholy. Ashes to Ashes (1980) was genuinely some kind of ceremony or rite in which a certain past was buried, in which he bid adieu (or hoped he did) to certain demons: ‘want an axe/to break the ice’. Listen to the strange, scary voices in the background, the truly mournful play-out, the far from comforting ending. The song is a confession written in sound: ‘I never did anything out of the blue … Want to come down right now.’ The paradox is that this Number One hit with its ‘iconic’ video may have reflected more of an all-time low than the fabled Low.

One of the photos of Bowie I saw online in the weeks after his death was taken in January 1997 at his 50th birthday celebrations, with Billy Corgan, Lou Reed and Robert Smith. This was the period when he finally found inner calm and displayed outer happiness, relaxed into himself. But take a look at this photo: doesn’t he look a bit wizened, a bit unreal, like a doll of himself or a plastic action figure of a late-era rock star? He’s sporting one of those fussy chin/lip beard doodads that were popular in the 1990s, just like any other middle-aged duffer trying to look young and trendy. He’s wearing something that looks like a cheaply ‘avant-garde’ high-street wedding suit with a novelty waistcoat. When he was at death’s door he looked wonderful, whereas now he’s clean and sober he looks etiolated, smudgy and grey; he looks, in fact, downright ill.

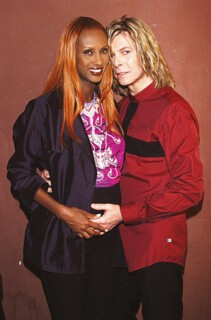

Bowie met the Somalian supermodel Iman in 1990 and they married in 1992. She seems to have dislodged something in him he’d hidden for too long, and he sobered up (though he continued to smoke like a troubled priest in a 1940s noir film). By swapping some of his alien ‘otherness’ for ordinary sociable life he found ordinary-folks happiness, ease in his skin, an end to constant ambient anxiety. Time calmed down, away from the on-off loop of addiction, which was great for life but maybe not quite as beneficial when it came to work. During these years, it felt like Bowie was rarely exciting by his own standards. Too much of his middle-period work comes across as a triumph of airless busyness over any kind of considered or memorable shape – dozens of weightless surfaces and battling signifiers in search of a missing hook or core. Listening to middle/late albums like Earthling (1997) or Heathen (2002), parts of which are perfectly pleasant or serviceable modern AOR, I kept thinking: is this the kind of thing Bowie himself would sit and listen to at home and get excited by? I really don’t think so; though there are moments when it’s all too obvious what he has been listening to. A track like Heathen’s opener, ‘Sunday’, sounds like a naked and embarrassing attempt to imitate the recently rejuvenated Scott Walker.

For the first time in his career he was chasing the zeitgeist, rather than looking airily back at its approaching shape. It can sound as if he has rushed into the studio with no more than a vague idea of doing something along the lines of whatever was currently ‘happening’ elsewhere on the fringes of pop/rock. (Is there a more depressing moment in his entire canon than the opening track of Earthling with its boilerplate drum and bass?) Maybe you can do that when you’re young and on fire (and when the material you’re half-inching is gold star), but he carried on trying to work like his younger self even when it no longer worked with golden ease. Bowie obsessives may be able to point to a few great songs scattered here and there, but for most of us Bowie’s middle period was a time when a lot of time could go by without him really impinging on your consciousness the way he used to do. It’s strange how, at a time when he was probably happier than he’d ever been, on works like Outside (1995), Earthling and Heathen, he continued to try and uphold the Bowie brand of weird, cold and untouchable. Look at the sleeve of Heathen, where all the stops have been pulled to make him look ‘weird’. The sleeves of Hours (1999) and Reality (2003) scream ‘workshopped by creative team’: they’re all over the place, too busy, with two or three clashing tropes. Compare such desperate-seeming incoherence with his records from the mid-1970s, when his album portraits were both subtle and subtly disorienting. It’s very hard indeed if not impossible to intend or design something uncanny. The uncanny results, it isn’t something you have much control over.

I wasn’t exactly scrupulous about following every new release during those years. The exception was 1995’s Outside – or, to give it its full title, 1. Outside. The Nathan Adler Diaries: A Hyper-Cycle; or, to give it its full full title: The Diary of Nathan Adler or The Art-Ritual Murder of Baby Grace Blue: A Non-Linear Gothic Drama Hyper-Cycle – which I had to listen to because I was interviewing Bowie for one of dozens of ‘comeback’-themed magazine stories. Although I was a good professional and played it to death, it disappeared like smoke and I found I could remember almost nothing about it a few weeks later except a vague sense of something ‘Bowie-ish’ having taken place – as if a surprisingly un-scary ghost had strolled through my front room. I could remember one song, or one line from one song – ‘Hallo Spaceboy!’ – and only because it teetered so shamelessly on the edge of self-parody. (In mid-period Bowie the more autopilot the track the more he tended to amp up his wideboy London brogue.) I found myself wondering, as I do with some postmodern artists (David Salle, for example): is this good because it’s a good David Bowie, or is it good by any standards? Or is he essentially, now, just imitating his own brand, because that’s what you do after a while these days?

Much as I found Outside entirely uninvolving and sometimes close to ludicrous, the minute I met him, the minute I was alone in a room with DAVID BOWIE, I melted. All this time, what we were consuming wasn’t this or that great/OK/below-par/dreadful music, but a cherished idea of Bowie, his chat, strangeness and charm. My half of that interview for Esquire mostly consisted of me grilling him about Young Americans, Station to Station, Low, and him plugging the ‘ideas’ behind Outside (outsider art, blood theology, chaos theory, ritual scarification, you name it). This was very much characteristic of the time. The days of interviews full of LA covens and drug confessions were over and he began to sound like any other old rocker with product to flog. For Never Let Me Down (1987) he ‘explained’ how he wrote such and such a song because of his concern with making a ‘statement’ about the homeless in the US. Ditto this one about Chernobyl. Ditto the one about (what else?) Margaret Thatcher. Those song ‘explanations’ are exactly the kind of thing you might have expected from someone not quite as smart as Bowie trying to do a Bowie: Bowie lite. Ironically, they gave the game away by being way too heavy. He could seem almost like a Pete and Dud parody of an up-himself rockstar.

‘Left field’ became a kind of default position – but it was more like a fond parody than the real future shocks that works like Low and Iggy’s The Idiot represented when they were released to a baffled world. Using Burroughs’s cut-up method was a liberating conceit to begin with, but after twenty or thirty years’ duty it began churning out a kind of homogeneous ‘Bowie-osity’ that turned the texts of his songs into an opaque shield, a way not to reveal anything very much at all. When Robert Christgau claimed that one of below-par-Bowie’s main traits was ‘the way he simulates meaning’ he got it just right. The more stress Bowie put on his songs’ ‘meaning’ the less they sounded meaningful to the listener.

It began to feel as though the music was there to facilitate the headlines and interviews and cover shots, rather than the other way round: the whole point was to keep the brand ticking over, the name alive. Legacy. The archive. Especially after he converted himself into a ‘celebrity bond’ in 1997. Bowie bonds were ‘asset backed securities of current and future revenues’. In other words, you were investing in the value of his song archive. By March 2004 they had been downgraded from A3 status to a notch above junk bond, then they were liquidated in 2007 ‘as planned’, at which point all the rights reverted to Bowie. In a way, things like the Bowie Bonds, or his much derided global Glass Spider tour of 1987, were far more in keeping with the future of rock – rock as marketplace and archive rip and nostalgia drip – than the old-fashioned idea of shock songs he tried to revive on records like Outside, all those putatively more ‘risky’, ‘eclectic’ raids into drum and bass, Nine Inch Nails and outsider art. The real business of creativity was gigantic tours, archive retrieval, branding, legacy.

While working on this piece to the background sound of ambient TV, all of a sudden I heard him call my name: I guess he had to crop up on a Vintage TV 1980s Special at some point. The featured clip was a live one from that notorious Glass Spider tour and he was doing one of my favourite songs off one of my favourite albums (‘Breaking Glass’ from Low) and – how can I put this? – it was a bit crap. His look was all bright primary colours and sharp angles, hair the colour of two-day-old crème fraiche. Every last trace of the song’s original strangeness had been scoured away, replaced by brassy professionalism. It had lost its heart to the starship trouper rocking everything up to 11 – at one moment he even threw in some old mime moves. His honking sax player had a big feather in his big, sad, I’m Such a Character hat. ‘You’re such a wonderful person,’ Bowie sings, then the girly chorus goes, ‘BUT YA GOT PROBLUH!’ ‘I’ll never touch you!’ – once, twice, again, over and over and over again, with something like nightmarish irony, almost as if he knew what damage he was doing to this lovely ghostly song, and how appalled many of us would be.

Watching Bowie selling himself to the world was a depressing sight, whereas I always found Low itself delirious fun; I never, ever, got the idea that it was depressive or depressing or ‘plastic soul’ or ‘alien disko’ or any of the other labels applied by a baffled rock press, a large leather-jacketed percentage of whom, let it not be forgotten, got this work entirely wrong at the time. Even though it now seems impossible not to hear that Bowie is opening up his heart for possibly the very first time, it was somehow judged not authentically rock and roll enough. Even a song like ‘Always Crashing in the Same Car’, which conveys a feeling of hopeless stasis, is, in sonic terms, sheerly lovely. It somehow manages to make the feeling of going round in gluey circles sound like some new kind of homeopathic druggy bliss.

In order to fall to earth, you have to be way up in the blackness and stars to begin with. What is the alleged Bowie ‘legacy’ if not a permission to dream, to fantasise, to get things wrong, to change horses in mid-air? The failure to communicate this is maybe why I find a lot of the new Bowie books admirable enough on their own terms but ultimately a bit disappointing – they seem all too sensible, linear, stuck safely inside certain conventions.

Paul Morley is best known for cheerleading the infectious ‘New Pop’ of the 1980s, and as a pithy postmodern interviewer. I worked (and played, and plotted) with him at the NME in the 1980s and still regard him with something beyond mere affection, but I don’t think even he would claim to be suited to writing any kind of ‘critical biography’. His 480-page The Age of Bowie (flap: ‘a startling biographical critique of David Bowie’s legacy’) was allegedly written in ten weeks, and fair play to him for managing to write a whole book in about the third of the time it might take (cough) some writers to squeeze out a tiny review, but – well, it has to be said, it shows. I’m completely mystified by writers who won’t let themselves be edited, and Morley is the Anti-Edit Man; I often wonder if he has an actual clause in his contract that forbids anyone erasing a single line. The Age of Bowie is fatally holed before it gets properly underway by a woefully self-indulgent, overlong introduction that completely skews the biographical timeline. The book is two-thirds over and we’re barely out of the Low/Heroes period: it’s like one of those painted demo slogans that start out in big bold letters then have to scrunch everything together by the end. The rest of Bowie’s life goes by in a flash, and the ‘critical’ part of this critical biography turns to hagiographical incense. Morley rushes through a jittery, excitable version of conventional biography, as if trying to break some kind of world land-speed record – but I’m not sure he has a single new fact or surprising interpretation. I went back to an earlier biography from my Bowie shelf – Christopher Sandford’s Bowie: Loving the Alien (1996) – to compare a page or two, and found I couldn’t put it down. Sandford is especially good on Bowie in the 1980s and 1990s. He deals with all the stuff that fancier or more fanciful authors wouldn’t touch with a bargepole: record company politics (the behind the scenes fiasco of Black Tie White Noise is a highlight), sales figures, advances, the drudgery of touring, backstage tantrums, fleeting romances, house moves and so on. The portrait of Bowie that emerges is fascinating: it makes you wonder about all the versions of him we’ve been given, and have taken at face value down the years. If Sandford shows him as flawed – not the perfect five-moves-ahead manipulator of Morley’s schema – it surely also shows a more faceted, human Bowie: another Bowie to Otherness Bowie, a mortal, fallible man.

For convinced superfans like Morley, Bowie was an advertising/design genius as well as a great pop musician; but a quick flick through later middle-period sleeves and ‘looks’ produces wince after wince. Music may have been the least of Bowie’s preoccupations during much of that period. He had a happy marriage, a seat on the editorial board of Modern Painters, various acting jobs and spots of journalism (as well as, apparently, endless tinkering with some kind of long-mooted novel/screenplay). Plus, of course, there was a never-ending stream of rock and lifestyle mag interviews – though it’s not clear how much they were a grudging duty insisted on by EMI after the huge sum of money it had invested in him. And then there was Bowie’s marriage to Iman, all arranged around a glossy Hello! magazine mega-spread. This event was subsequently talked up (rather unconvincingly, it has to be said, as if he were trying primarily to convince himself) by Brian Eno, who claimed his friend was a far-sighted celebrant of some strange new ritual/cultural paradigm.

I don’t know that The Age of Bowie even begins to come to terms with the manifold contradictions of Bowie’s ‘legacy’. My own feeling is that by the time we get to the end of the book we have learned more about Morley than we have about Bowie. Still, at least it possesses a nutty, Maileresque kind of grande ambition, whereas Rob Sheffield’s On Bowie reads more like a series of affably intimate blog entries. (You can get an idea of Sheffield’s jauntily faux-naïf tone from the titles of two of his previous studies: Talking to Girls about Duran Duran: One Young Man’s Quest for True Love and a Cooler Haircut; and Turn around Bright Eyes: A Karaoke Journey of Starting Over, Falling in Love, and Finding Your Voice. I don’t know about you, but I began to lose the will to live somewhere during the second subtitle, and the word ‘journey’ thus employed is banned in our house.) Sheffield lost my sympathy as soon as he suggested that Nicolas Roeg didn’t know what he was doing in The Man Who Fell to Earth, which he regards as some kind of hopeless artsy mess, redeemed only by Bowie’s presence. (Rather than, say, a precisely plotted allegory about certain subjects that had an obvious pull for Bowie: loss of innocence; self-willed fall through excess and addiction; media overload; English artfulness and reserve in the landscape of American spectacle and get-it-now emptiness.)

Both Sheffield and Morley manage some sharp, rapt writing on Bowie’s LA-to-Berlin crack-up period, but given the richness of the material, anyone who couldn’t get a few good lines out of it should be drummed forthwith out of the rock writers’ guild. Sheffield’s On Bowie (white cover with red and blue Aladdin Sane flash; 197 pp.) also bears a spooky resemblance to Simon Critchley’s On Bowie (white cover with red and blue Aladdin Sane flash; 207 pp.), ‘a version of which was first published in 2014’. Critchley’s elegant text is far more to my taste than the many encyclopedic volumes in vogue at the moment. He makes use of heavyweight theory names, but doesn’t belabour the reader with academic lingo. Tying together early and late Bowie he arrives at a ‘Lazarus’ figure occupying a figural ‘space between the living and the dead, the realm of purgatorial ghosts and spectres’. It probably helps that he originally spun this steely web without any pressure to conform to the post-death consensus. (Bizarrely, a recent review in the Observer called Critchley’s work ‘hastily written’, while Morley’s ten-week blitz was termed an ‘aide memoire’. Go figure.)

Simon Reynolds, on the other hand, represents the geography teacher tendency of rock crit, all muscular spadework and measured appreciation. He is enviably industrious, his books are scrupulously researched, and he gives the impression of having heard every B-side ever recorded. At its best, his approach can have a cumulatively enlightening effect, but he can also come across like a jovial cultural studies lecturer dutifully ticking off bullet points. Back in the day, Reynolds always seemed to be trying to uncover some new trend or invent an exciting new micro-genre. Now that the future looks a lot less certain, he specialises in turning over the rich dark humus of the recent past, and Shock and Awe (a baffling and maybe even tasteless title) is a pre-punk book to go with his post-punk opus Rip It Up and Start Again (2005). In terms of covering every last inch of ground it can’t be faulted. What’s less evident is an invigorating theoretical framework or overview – something that might shatter snoozy old paradigms. I got to the end of the book without being any wiser about how we’re living today with the backwash of Glam (unless, of course, you want to delve into certain foul nooks to do with historic sex allegations). A full and convincing explanation of the nature of Glam’s ‘legacy’ never quite arrives; instead, there’s a scattershot treatment in the final section’s inevitable list/diary/round-up, the weakest part of the book by a considerable way.

When Reynolds manages to combine high and low culture, like two tipsy strangers at a wild party who would never have met otherwise, it can be great – a sort of local version of Benjamin’s yearned-for flash of temporal insight: history with a lit fuse. But over the course of 650 pages it begins to feel like trying to see every single ‘iconic’ work in a major gallery in one exasperating go. (An excerpt from Reynolds’s index: ‘Hilton, Paris; Himmler, Heinrich; Hitler, Adolf; Hobsbawm, Eric; Hockney, David; Holder, Noddy’.) One problem with this kind of polymorphously clued-in work is that the author has to pretend to a functioning expertise in a dozen different disciplines (sociology, aesthetics, fashion, musicology) and thereby opens himself up to the jibes of actual experts in those areas. For instance, Reynolds asserts that ‘Magic and self-aggrandisement go together,’ and that ‘Aleister Crowley’s dictum “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law” enshrines this egocentric world view of the disobedient child.’ Well, no, it really doesn’t; it does more or less the opposite. ‘Do what thou wilt’ doesn’t mean ‘do whatever you please and bugger the consequences,’ it means find the one thing you are meant to do and devote yourself to it.

I’m not sure how seriously Reynolds wants us to take some of this stuff. You have to wonder if all the Nietzsche-boy references, say, aren’t a bit heavy for Marc Bolan’s frail wee shoulders. I’ve always thought of Glam as a kind of Op-Rock: the lines that made it up are pretty broad and not that special on their own, but taken together up close they can really go to your head. How seriously should we take a Bolan masterwork with lyrics that run: ‘Did you ever see a woman coming out of New York City/With a frog in her hand?’ Isn’t this really just the Op-Rock equivalent of ‘How Much Is That Doggy in the Window?’? Was Bolan really Reynolds’s troubled Wildean dandy, or just an empty chancer who did a few lines and babbled at any interviewer from the pop trades, giving them zingy fibs and fabulations? I recently caught Bolan on afternoon TV singing ‘Get It On’ and his appeal struck me as uncomplicated and elemental. Musically he was from the school of Chuck Berry, but instead of a pervy black granddad, Bolan was an impossibly cute girl-boy in pink satin, Mickey Mouse T-shirt and grandma shoes. He really did look androgynous: willowy and hard at the same time, softly inviting and unthreatening but with enough of a hint of lippy carnality to keep a young female fan base interested. And he seemed especially sexy alongside the rest of the programme’s line-up: Noddy Holder in a big flat cap, Paul Simon’s comb-over, a very sweaty Marvin Gaye in a bobble hat, and ELO’s Jeff Lynne with that scenery-eating perm.

When it comes to David Bowie I think Reynolds gets the tone exactly right, and pulls together a really superior potted Bowie biog. In this telling, the years that matter aren’t just Berlin and Los Angeles but also 1964-70, the apprentice years leading up to his Glam breakthrough. I was delighted to see Reynolds being properly respectful to a big influence on Bowie that other critics shy away from: Anthony Newley, a Light Entertainment renaissance man – actor, singer, songwriter – who trod the thin line between shameless MOR schmaltz and nervy conceptual daring. This is a great lost period of pop history, with its dozens of little papers and magazines, fan clubs, pop agony aunts and countless queer cross-currents: oscillation in and out of the closet (and the closet sometimes even a site of uncanny power); the dissolving together of timeless theatricality and pop temporality; deals done in gay drinking clubs, golden youths picked up and polished then abandoned by Machiavellian gay managers. (One key difference between Mark Feld and David Jones was that the latter was maybe happier to go that extra inch.)

We might have expected Blackstar to be fatally earnest, with everything stripped away leaving only the most bitter daily bread, the mortality blues – a kind of Bowie unplugged. But he chose to go another way, out on a limb for one last bout of serious fun, as scattershot cut-up ‘pretentious’ as ever. Glints of this, splints of that, ambiguous headlines, crowd-sourced jazz noise, theological dust-up: it’s all still there, just as it was in the early bird days. The video for Blackstar’s title song looks like it’s set in the world of Ernst Jünger’s a-chronistic sci-fi novel, Eumeswil: ancient Egypt or Rome, with Bowie as 23rd-century schizoid shaman. One last play with time and identity: a combination of Far East worship and fear, bandaged eyes (ironic fate for a master of image) and politics as primal myth. This was always the lure with Bowie: to see how his mind worked, to find out what it had been turning over lately, see what he’d pressed into the circuit and what came out the other end. Which is why the 1970s worked so well. Who could have predicted Young Americans and Station to Station, or Low and Heroes? It was like the zeitgeist had its loving arms around him, pulling him forcefully by the well-tailored sleeve, pushing him further, so that at a certain point he almost couldn’t tell any longer if the stuff he was taking in and processing was benign or demonic, darkness or light, and no longer cared. He simply accepted the dare. Blackstar is Bowie returning to a well-worn spot where he wonders about belief, religion, the cross around his neck. Heaven or hell, who knows, and maybe the key to the sacred is when you accept that you’ll never know and accept that you need both.

He left possibly the loveliest image of all right to the end. It’s part of the promo session for Blackstar taken by a longtime friend and photographer, Jimmy King, and released on Bowie’s 69th birthday. He’s out in the open, suited and booted to rip through his final curtain. I may not be the biggest Bowie fan in the world, but I still open this pic on my desktop when I have the mean reds and need a spiritual kick up the arse. One final uplifting performance of self! He looks like a little old man, a greying leprechaun, but also younger than springtime. He’s on the finishing line of life, but his body is folding into an arc of pleasure, as if it’s about to leap off into one more flimsy unknown. All the little black stars are tunnelling within, but here he is in meeting-the-accountant suit and soles, and meeting the monster laughing fit to burst. Pure joy creasing the familiar face. Maybe he’s even laughing at one last silly Narcissus reflection: ‘Just look at me, I’ve finally become that god-damned laughing gnome after all.’ A wistful kind of collective love enveloped him at the end, when the world was won over by the dignity of his not selling his failing health to the global media. Finally, he had everyone on side before he had even said a word. Finally, he let the words, music and images speak for him, with no scare quotes or cloudy art-speak verbiage or winning London Boy wink.

On The Next Day (2013) and Blackstar Bowie seems more present, as though illness had had a calming or restorative effect alongside the natural grief. Surely one of the first (and potentially worst) strikes of illness for any performer is that it strips away image (false or otherwise), a large part of a star’s capital no matter their age or how wryly they may now regard the other self sent out to do battle on the stages and screens of the world. But it’s also possible that sloughing off the brittle patina of image can bring unexpected revelations, a nakedness that restores context. Before you know it you may hear yourself say: ‘Maybe I can do anything I like now, after all.’

The cliché is that illness shows the mottled wolf skull beneath the pampered skin – but it can also be a welcome corridor, returning you to places you’d left behind. Suddenly, in the antiseptic hospital room one afternoon, you remember them all: so many unstarry things. The way shadows caressed a wall in a vacant lot in Berlin, one rainy November day in … 1976, was it? A scrum of garish fans surrounding you on Sunset Boulevard. Postwar London, whose bombsites seemed to harbour all the time in the world. Make-up counters, listening booths, bakelite curves, saloon bar mirrors, diamanté in a jewellery box that played Swan Lake when the lid clicked up. The strange snake hiss of early TV. A new world inventing itself in the middle of the 20th century, when images were things that genuinely shocked, carriers of forbidden knowledge. Something torn from a Hollywood gossip mag or a single image in a clunky library book on Surrealism could literally change your life. Penguin Modern Classic paperbacks; Genet and his cruisey down-is-up theology; Andy and his abyssal Wow. The surprising new meanings ‘love’ could develop far away from home. Backstage’s suffocating air. The way she walked; the way she talked.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.