Ive never been voluntarily committed, or sectioned, either to an asylum or a locked psychiatric ward, but I’ve visited a fair few in my life: it goes with the odd profession of drug addiction – as do weeks and months closeted in rehabilitation centres and private clinics. My regular visits to the locked ward at the Royal Free Hospital in London, when I was still in my teens, made such a vivid impression on me that I’ve gone on trying to imagine these singular – yet synecdochic – spaces throughout my writing career. I remember also that during my Royal Free period I was reading R.D. Laing’s The Divided Self – so I came to an awareness both of the state-mandated asylums, and of those who radically opposed them, at more or less the same time. Still, I don’t believe I’m atypical, either among the psychically distressed or those who’ve never suffered from mental affliction, in maintaining a paradoxical view: the asylum is at once an essential refuge, and – in the words of Erving Goffman, one of its most effective critics – a ‘total institution’, which, under the guise of protecting its patients, all too often succeeds only in dehumanising them.

All of which made me interested to see Bedlam: The Asylum and Beyond at the Wellcome Collection (until 15 January), an exhibition that aims to convey … well, what precisely? Certainly not what it feels like to enter these maddening realms, where the air – at once shitty and aseptic – is rent by haunting cries, and patients are pumped so full of major tranquillisers that they schuss from their plastic stacking chairs to the floor. I went on a Sunday afternoon, so the place was fairly crowded, though nothing like as packed as our mental hospitals. (There were exchanges in the not-so-crowded Commons recently, between the prime minister and MPs concerned by the government’s failure to make good on promises of ‘parity of esteem’ between mental and physical health in respect of NHS resources.) But despite Theresa May’s bluster about increasing funding, the reports from the front line are dire. Two friends of mine – one a charge nurse, the other a consultant psychiatrist – are both currently facing disciplinary actions from their respective trusts. Their alleged malpractices perfectly illustrate the ambivalent attitudes conscientious psy-professionals have towards the asylum: both have outed administrators for discharging mental patients in order to fulfil quotas, and both have been censured for criticising clinical practice; which, even in this day and age, largely consists of making free with the old liquid cosh. That’s the problem with asylums: it’s next to impossible to know whether you’re better off being in one, or completely out of it.

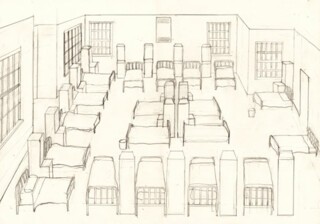

What the Wellcome’s exhibition does is attractively to present the ugly truths: visitors encounter first Eva Kotátková’s Asylum (2013), an assemblage of oddities – wire models, dummies, découpage – laid out on a big black table. Apparently these artefacts are ‘periodically animated by performers’, but when I saw them they just sat there, looking rather too archly artful to convey anything much about the fretting and strutting of the sequestered. And I felt this was the problem with pretty much all the work on show produced by visitors rather than inmates. To adapt a jokey sign from the days before parity of esteem: you don’t have to be mad to work on this subject matter – but it helps. Just a few moments examining James Tilly Matthews’s beautifully executed pen-and-wash drawing of the ‘air loom’ he believed to be the cause of his psychosis was enough to transport me into the crepuscular realm of the seriously disturbed, but the works of contemporary artists ‘engaging’ with the asylum and its inmates left me right where I was: on the Euston Road.

Matthews was confined to the Bethlem Hospital, commonly known as Bedlam, when it was sited at Moorfields. That wasn’t its first iteration: the history of Bedlam as either refuge or place of imprisonment for the mentally ill goes back to the medieval period, when the hospital was established as a priory at Bishopsgate by the London Wall. Over the following nearly seven hundred years Bedlam has changed from being somewhere alms were dispensed to the mendicant to being synonymous with mental illness itself; one thinks of Tom o’Bedlam, who urges his listeners in an anonymous 18th-century ballad: ‘Come dame or maid, be not afraid/Poor Tom will injure nothing.’ Matthews, as well as working on the air loom, made beautiful plans for a new Bedlam, since by the early 1800s the baroque palace of an asylum, designed by Robert Hooke, had fallen into serious disrepair. Matthews’s designs – elegant and neoclassical – were passed over, and the great grey superstructure of the new Bedlam arose at St George’s Fields in Southwark instead, topped off by the weirdly elongated dome which, together with the core of the building, still remains, though now it houses the Imperial War Museum.

It was this Bedlam that Dickens passed on his haunting night walk. ‘Are not the sane and the insane equal at night as the sane lie a dreaming?’ he wrote. ‘Are not all of us outside this hospital, who dream, more or less in the condition of those inside it, every night of our lives?’ Dickens wasn’t alone in apprehending that insanity – originally a legal, not a medical category – was as much contextual as absolute. There have always been those willing to engage with the delusional rather than warehouse them, and the Wellcome exhibition – if you take the time to stop and stand, and read a lot of info-panels – is a competent exposition of the polarities that underlie the history of the asylum: the alternation between mentalist and physicalist accounts of mental pathologies, and the push-me pull-you between restraint and toleration. Perhaps the greatest paradox of the grim mid-19th-century asylums that glowered for upwards of a century on the outskirts of British cities is that they were built with the best and most humane motives: ‘No hand or foot will be bound here’ was blazoned across the pediment of the Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum when Prince Albert opened it in 1851. Of course this was an injunction soon enough set aside, just as the earlier proclivity for treating asylum inmates as objects of fascination for tourists had been set aside by enlightened reformers, only to creep back in again.

The counterpoint to the British Bedlams is the example of Geel, the agricultural community in Belgium which, also since the medieval era, has been a refuge for the psychically distressed, but with the distinction that no hand or foot really is bound there. ‘The Geel question’, as it became known to generations of British alienists and then psychiatrists, was how did it work? How was it that the mad and the sane could live together in such apparent harmony? The answer is encrypted in deeply dug folkways, and not readily transplanted to foreign soils. The wilder anti-psychiatric asylums of the 1960s, such as R.D. Laing’s Kingsley Hall, get markedly less attention in the exhibition, and I suspect rightly so. Instead there are film loops and images of wacky advertising for psychiatric drugs, because for most of the mentally ill that’s their asylum now: the glutinous pacificity that comes in a bottle labelled Largactil (an unlovely compound which, I learned, was arrived at by combining ‘large’ and ‘action’).

The large action – initiated by Enoch Powell, of all people, in a speech in the early 1960s – was the closure of the old asylums, which had upwards of a hundred thousand inmates mouldering in the back wards set along their interminable corridors. By then Bedlam had hoiked up its stony skirts and moved again – this time to the deep south of London. I went to an open day there a couple of years ago, and wandered its leafy byways, between low-rise brick blocks, before stepping into the museum (at that time housed in a Portakabin), where I saw Caius Cibber’s petrified personifications of Melancholy and Raving Madness, which had adorned the gates of the 17th-century asylum. The latest Bedlam – like the Wellcome exhibition – is light and airy, and there’s no sign of restraint – but it hasn’t got enough beds, so once again Tom o’Bedlam is afoot, in the form of homeless mentally ill people, wandering the city streets.

I can thoroughly recommend this exhibition, but only really for people who are too restless to read the book published in association with it. Mike Jay’s superb This Way Madness Lies (Thames & Hudson, £24.95) is as good a book on the subject as I’ve read – and I’ve read a few. Jay co-curated the exhibition, but it’s here, between stiff boards rather than well-hung walls, that I found the leisure to appreciate the superb range of artefacts and images he has assembled; while the text itself exhibits all the lucidity you could wish for when struggling to apprehend this most disturbing and problematic of subjects.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.