In 2006, the British Library bought a huge archive of Angela Carter’s papers from Gekoski, the rare books dealer, for £125,000.* It includes drafts, lots of them, a reminder that in the days before your computer automatically date-stamped all your files book-writing used to be a clerical undertaking. It has Pluto Press Big Red Diaries from the 1970s, and a red leatherette Labour Party one, tooled with the pre-Kinnock torch, quill and shovel badge. There are bundles of postcards, including the ones sent over the years to Susannah Clapp, the friend and editor Carter would appoint as her literary executor, which formed the basis of the memoir Clapp published in 2012; there’s also one with an illegible postmark, addressed to Bonny Angie Carter and signed ‘the wee spurrit o’yae Scots grandmither’. And there are journals, big hardback notebooks ornamented with Victorian scraps and pictures cut from magazines, and filled with neat, wide-margined pages of the most nicely laid-out note-taking you have ever seen. February 1969, for example, starts with a quote from Wittgenstein, then definitions of fugue, counterpoint, catachresis and tautology. Summaries of books read: The Interpretation of Dreams, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, The Self and Others. All incredibly tidy, with underlinings in red. And exploding flowers and nudie ladies stuck on the inside cover, as if in illustration of The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman, which Carter would have been working on at the time.

What was I looking for when I went to look at the Angela Carter Papers? To begin with I didn’t really know. Partly it was professional completism. Journalists are supposed to do as much research as possible, so it was part of the job, I decided, to take a look at this amazing public resource. Partly there was something cultic about it. There aren’t many places I love more than I love the British Library or writers I love more than I love Angela Carter, so of course I was going to take this chance to sniff at the sacred stationery, served on huge wooden trays by hushed BL staff. But mostly I was looking for an approach. Carter was 51 and at the height of her fame and family happiness when she died in 1992. Her instructions for the work she left behind were that it should be used in any way possible – short of falling into the hands of Michael Winner – ‘to make money for my boys’: Mark Pearce, her second husband, and Alexander, the couple’s son, born in 1983.

As Edmund Gordon says towards the beginning of his biography, Carter was never so widely acclaimed in life as she would be in the weeks and years after her death. The tributes were long, sometimes fulsome, always affectionate, and full of great table talk and funny stories from Carter’s ‘flotillas’ – Carmen Callil’s word – of famous friends. That happens when a well-liked person dies before their time, especially when the death has the long lead-in afforded by cancer treatment, and when they leave a younger partner and small child. It’s probably why Clapp’s memoir feels a bit overstuffed as it gets started. All those cats and birds and scarlet skirting boards, as if to hide and plug the hissing hole.

Except that Carter the mythological being was already up and running when Carter was alive and well. One of her ‘most impressive and humorous achievements’, Lorna Sage, her friend and cleverest critic, once wrote, ‘was that she evolved this part to play: How to Be the Woman Writer. Not that she was wearing a mask exactly: it was more a matter of refusing to observe any decorous distinction between art and life.’ One aspect of this, Sage wrote, was the ‘fairy godmother’ act that Carter performed more and more as she grew older and more settled: the woman of independent means who has done quite well for herself, as Carter described Charles Perrault’s version of the figure, who waves wands and make things happen, transcending biological relatedness and bourgeois property law. Carter, Sage proposes, ‘birthed herself’ into that position through years and decades of intellectual and emotional labour, and it’s that labour that interests me more than the final effect, and so I was hoping the archive would give me a way of getting a bit of air in.

‘Writing … certainly doesn’t make better people, nor do writers lead happier lives,’ Carter wrote in the 1980s in probably the first thing of hers I ever read, a dashed-off contribution to one of the many feminism-and-writing anthologies that were being published at the time. She gave Baudelaire as an example, the discovery of whose poetry, she once said, had been ‘like having my skull opened with a tin opener and all its contents transformed’. Manifestly not, however, the work of a happy person – ‘and he was a shit to boot’. Her other male literary heroes, Carter continued, were Melville and Dostoevsky, ‘both rather fine human beings, as it turns out, but both … so close to the existential abyss that they must often, and with good reason, have envied those who did not have inquiring minds.’ Was she saying that it seemed to her impossible to do good work, and be a decent person, and experience just about tolerable levels of peace of mind?

‘The sense of limitless freedom that I, as a woman, sometimes feel is that of a new kind of being. Because I simply could not have existed, as I am, in any other preceding time or place.’ Being, she went on, ‘the pure product of an advanced, industrialised, post-imperialist country in decline’ – and with the boon of birth control to free her from puerperal fever and multiple pregnancy – ‘I feel free to loot and rummage in an official past, specifically a literary past’ which ‘for me has important decorative, ornamental functions’ but is also a ‘vast repository of outmoded lies’. An art that rummages in dead falsehoods sounds depressing, except that Carter is describing the method of Nights at the Circus (1984) and Wise Children (1991), both comedies of confused parentage and obfuscated reproductive function, and the two of her novels most often described as ‘joyous’ and ‘carnivalesque’.

‘But, look, it is all applied linguistics. But language is power, life and the instrument of culture, the instrument of domination and liberation. I don’t know.’ In a life and work through which Carter made and unmade all sorts of things, root and branch, it sometimes seems that the one constant was the pride she took in being a good socialist of a quite straightforward sort. (It seems, from Gordon’s account, that socialism was just about the only thing Carter wanted to inherit from her mother, a lifelong Labour supporter. Unlike her adored father, who had been, she was pained to discover, a secret Scottish Tory – she found his membership card in his papers after he died.)

A lifelong believer in writing as a public, material art form, a proud member of the ‘inquiring rootless urban intelligentsia’ brought into being by the 1944 Education Act, would Carter have been pleased to find her papers in public ownership? Better that than pawed at by some oligarch collector, like the creepy Grand Duke in Nights at the Circus, but whether she would have been pleased or not isn’t really the point. The point is, so much of Carter’s work was so polished by the time she finished it, and further polished by time and praise, it becomes easy to miss the force and effort that made it, the work, the strength of mind. The BL’s archive is a record of that labour, marvellous and daunting, sometimes upsetting. And the letters in particular record an extraordinary social circle. There’s as much to learn from the letters people wrote to Carter as from Carter’s writings themselves.

Angela Olive Stalker was born to a London mother and Scottish father in Eastbourne in May 1940 and raised in Balham in South London. She married Paul Carter in 1960 when she was just twenty, then moved with her husband to Bristol, where she wrote four novels in quick succession and started publishing her journalism in New Society magazine. Her third novel won a travel award of £500, which Carter used to leave her husband and move to Tokyo, where she was based for the next two years. She returned to Britain in 1971, settling at first in Bath and then from 1976 in Clapham, where she lived with Pearce and raised her son and became ill with the lung cancer that would kill her in February 1992.

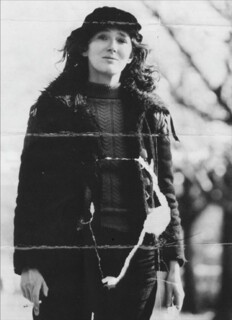

Her early books ploughed a lonely, unconscionably peculiar furrow between kitchen-sink realism, cheesy sci-fi gothic horror and a sophisticated, scholarly speculative fiction of the sort that readers found easier to manage when authored by distinguished-looking foreign gentlemen – Nabokov, Calvino – rather than a scruffy young lady in a combat jacket with a curly Jimi Hendrix crop. But the world caught up with her in the 1970s with the spread of women’s liberation and the founding in Britain of the feminist Virago Press.

Carter was one of the first authors Virago recruited to its editorial board, and her magnificent long essay The Sadeian Woman (1979) was one of the first titles Virago commissioned. Some feminists, Gordon writes, found the book extremely offensive, including Andrea Dworkin (‘If I can get up … the Dworkin proboscis,’ Carter commented, ‘then my living has not been in vain’), but for youngsters like me, coming to feminism in the anti-porn-fixated 1980s, it was the first book about sexual politics that really seemed to make sense. The opening proposition still fills me with huge excitement: ‘We do not go to bed in simple pairs: even if we choose not to refer to them, we still drag there with us the cultural impedimenta of our social class, our parents’ lives, our bank balances, our sexual and emotional expectations, our unique biographies – all the bits and pieces of our unique existences.’

In other words, sex, which people pretend to believe is intimate and private, actually has an irreducible public, political dimension. It follows, then, that pornography, the art of getting all the secret stuff out in public, is an irreducibly political form. Sade, we know, mostly wrote his wank-manuals while in prison during the French Revolution. He was a man of specialised and unpleasant sexual interests, but he was also a radical political theorist, with much to teach about the dialectics of sex and power, for those who dared to learn. In Justine, we can read an allegory about the dangerous mystique of feminine virtue. In Juliette another allegory, about the rationality of vice. Flesh always ‘comes to us’ out of history, politics, economics, as do all attempts at its ‘repression and taboo’.

Carter, Gordon writes, struggled for years in the writing of The Sadeian Woman, frequently feeling she’d bitten off far more than she could chew. But the finished book has the whooshing energy of deep release and satisfaction, of a writer getting something burdensome and important completely off her chest. This makes it both interesting and valuable and very funny and entertaining. It’s most like – weirdly enough – D.H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature, another book that gets its energy from poking holes in just the right places to release all that built-up sexual tension. (Carter had a lifelong love-hate relationship with Lawrence, who she grudgingly conceded was English literature’s greatest modern writer as well as its biggest stocking fetishist, as outlined in ‘Lorenzo the Closet Queen’, her brilliant essay on Lawrence and lingerie with special attention to Women in Love.)

Pornography, as Sage writes, was not the only sort of ‘practical fantasy’ that engaged Carter at this time. She had published her translation of Perrault’s spruced-up folk tales in 1977 and had been working on her own remixes of Bluebeard, Beauty and the Beast, Snow White, Little Red Riding Hood. The tales collected in The Bloody Chamber (1979) were succinct and elegant and exquisitely put together, glinting with fresh ideas about cruelty and sexuality and desire and wildness; they also contain some of the most sensuous shocks words were ever heir to. The bit when Beauty’s skin is licked off and she revels in the ‘beautiful fur’ beneath it. The Erlking’s songbirds, each with ‘the crimson imprint of his love-bite’ on her throat. For all these reasons – and because of the film Neil Jordan made of it, The Company of Wolves (1984) – The Bloody Chamber quickly became a set text in schools and universities. ‘I had no intention … of writing illustrative textbooks of late feminist theory to be used in institutions of education,’ Carter once wrote, ‘and the thought that I’m taught in universities makes me feel rather miserable.’

The novels that followed were, if anything, even more teachable in their craft and cleverness: too gorgeous, too ingenious, I used to think sometimes, like the Fabergé eggs the count tempts Fevvers with in Nights at the Circus, until she hatches a train to engineer her escape (and, yes, I do suspect that’s why Carter mentioned the eggs in the first place: she set it up so readers would read the image in exactly that way). ‘Whatever spirited arabesques and feats of descriptive imagination Carter may perform, she always comes to rest in the right ideological position,’ John Bayley wrote in a notoriously slighting 1992 review: the ballet idea works well, but otherwise he’s a bit tin-eared. A ‘moral pornographer’, Carter called herself sometimes; she could also have called herself an ideological choreographer. It’s not about getting into the ‘right’ positions but into interesting and surprising ones. It’s about complexity and discipline and poise and control.

It’s true that as Carter grew older, her work got noticeably kinder, but the interest in revolution, sexual and political, never disappeared. In Nights at the Circus, the twist at the end reveals that Fevvers and Lizzie, travelling from St Petersburg to Yokohama on the Trans-Siberian Express, have all along been spying for Lenin (‘But Liz would do it, having made a promise to a spry little gent with a tache she met in the reading-room of the British Museum’). And where did Fevvers come from anyway, but from an egg laid by the divine marquis himself? ‘Justine is woman as she has been until now, enslaved, miserable and less than human,’ Apollinaire wrote of Sade, and Carter often quoted. ‘Her opposite, Juliette, represents the woman whose advent he anticipated, a figure of whom minds have as yet no conception, who is rising out of mankind, who will have wings and who will renew the world.’

‘I am easily confused by my own roots,’ Carter wrote in a piece for New Society in 1976. Her roots were quite confusing, as most people’s are. Her father, Hugh Stalker, was a Scottish working-class boy made good, a journalist who worked nights at the Press Association in Fleet Street. She described her mother, Olive Farthing, as being ‘from the examination-passing working classes’, meaning that she had won a scholarship place at a grammar school, then left with no qualifications, at the age of 14. Olive worked a cash register at Selfridges before the birth of the Stalkers’ first child, Hughie, in 1928.

Angela, their second child, was born at the beginning of May 1940 in Eastbourne, where Olive had decamped to be near Hughie, who had been evacuated there. A couple of weeks later, the evacuation of Dunkirk made the south coast seem less safe than it had done, so Olive’s mother suggested that they move to Wath-upon-Dearne in south Yorkshire, the pit village she had left for London decades before. And so, Olive, Hughie and the baby lived in a miner’s cottage with Olive’s mother until the war ended in 1945.

‘My grandmother … was an old woman, squat, fierce and black-clad like the granny in the Giles cartoons in the Sunday Express,’ Carter wrote in an essay published in 1976. ‘I think I became the child she had been, in a sense, for the first five years of my life … tough, arrogant and pragmatic.’ Carter never wrote with such warmth – or gave such prominence to – her actual mother. ‘With the insight of hindsight, I’d have liked to have been able to protect my mother from the domineering old harridan, with her rough tongue and primitive sense of justice. But I did not see it like that then.’

Gordon gives short shrift to the more marvellous of Carter’s claims – that her grandfather shook hands with Lenin, that Grandma used to wear a Votes for Women badge – and quotes a confession Carter once made to a friend in a letter: ‘I do exaggerate, you know … I exaggerate terribly.’ But the psyche has its own rules about such matters, and Carter herself was convinced that what she called her ‘core of steel’, her ‘sense of my sex’s ascendancy in the scheme of things’, ‘a natural dominance, a native savagery’ had come straight to her from her grandma, skipping a generation on the way.

But when the Carters returned to the family home in Balham, things got strange. A ‘dream-time’, the adult Angela called it, with an ‘elusive flavour’: ‘it was as though we were stranded, somehow’ in a ‘curious kind of deviant middle-class life’. There were treats, lots of them, ‘cream with puddings and terribly expensive soap’; there were ‘all the impedimenta of a bourgeois childhood, a doll’s house, toy sewing machine, red patent-leather shoes’. But the age gap between Angela and her brother was so enormous that she was, basically, a lonely only; and her father’s shift-patterns made for ‘a household in which midnight was early and breakfast merged imperceptibly into lunch’. Angela seems often to have been kept up late as company for her mother: unsurprisingly, she grew insomniac and anxious. Or, as she proudly exaggerated later: ‘I very rarely slept.’

Hughie married in 1954, when his sister was a teenager: Gordon interviewed both him and his wife at length. ‘I thought her mother was crazy,’ Joan said, bluntly. ‘Her mother clung to Angela. She didn’t want Angie to grow up.’ A hanky was placed behind her head if she sat down in public. She wasn’t allowed to go to the lavatory on her own until she was ten or eleven. She later told a friend that her mother ‘regularly sniffed her discarded knickers’, which may have been another exaggeration, or may not. And Olive liked to feed her daughter up. Angela was always destined to be ‘a big girl’, as she would later write of Fevvers, wide-boned and five foot nine by the time she was a teenager; but she also weighed six or seven stone by the time she was eight, and was soon ‘obese’. Her childhood nicknames included Fatty and Tubs and Fat Angie and Chubster. She became, Gordon writes, ‘almost wholly dependent’ on her mother ‘for reassurance and affection’ because she didn’t really have any friends.

It’s striking, Nicole Ward Jouve observed in a 1994 essay, that throughout her many rummages in the remnant bins of gender stereotype, Carter ‘never writes from the vantage point of the mother. Always that of the daughter.’ Ward Jouve also recalled how ‘affronted’ she felt when she first read The Sadeian Woman, in which Carter seemed to endorse the cruelty of Eugenie’s revenge on her mother in Sade’s Philosophy of the Boudoir – double rape with an added syphilis infection, after which the mother is sewn up and ordered to kiss her daughter’s behind. (‘A Sadeian rite de passage into full sexual being’, apparently. And ‘a characteristic piece of Sadeian black humour’.) Carter’s point – apart from the obvious one that Sade writes fantasy – is that Eugenie’s brutality is ‘some indication of the degree of repression from which she has suffered’. The mother must be punished for her sins against the daughter, for banning her from enjoying her own erotic life.

Feminists always think it’s men who are the object of their quarrels, Sage observed, but it often isn’t. Time and time again, the really poisonous conflict is with the women of the preceding generation, the ground they gave and the mistakes they made in loving themselves and their daughters, not wisely but too well. In this respect it’s interesting that Carter was often vehement in her dislike of slightly older women writers, such as Joan Didion, Edna O’Brien and Jean Rhys, whom she claimed to find victim-like. Such women also, one can’t help but notice, had the fragile slightness her mother had but she didn’t, in their bodies and in their works. Even after giving birth herself, Ward Jouve noted, Carter never wrote good parts for biological mothers. But she did warm a bit to non-biological mothering: the prostitutes who care for the infant Fevvers in Ma Nelson’s brothel, the tangled parentage of the Chance sisters and the way they care for ‘our Tiff’.

And there was the hilarious, terribly touching spectacle of the very last piece of work Carter completed: a Pythonesque television animation called The Holy Family Album, which satirised ‘God the father’ and the many pictures taken by Him through the centuries of his ‘only son’. ‘She didn’t even know where babies come from,’ Carter voices gently, over old frescoes of the Virgin Mary, with hosts of angelic singing. ‘Then came her enlightenment. It seems to have come as something of a shock.’

In 1951, Carter passed the 11-plus and won a funded place at Streatham Hill and Clapham High, a girls-only direct-grant grammar school. She wrote about ‘the glum, sullen loathing that overcame me’ as she ‘daily slouched and dawdled’ her way there, and how much she hated maths and PE. But she was great at English and French – a teacher introduced her to Baudelaire and Rimbaud – and she was expected to do well in her A-levels and get a place at Oxford. In the event, she didn’t – Gordon repeats Clapp’s story about Olive saying she, too, might come along and live in Oxford to look after her clever daughter. At this point Angela gave up. Hugh found her a job a bit like the one he had started out in, as a junior reporter on the Croydon Advertiser. But her early career was undistinguished. Sent to cover the AGM of the Croydon Deaf Children’s Society, she came back without the story, because, she said, ‘they hadn’t heard her knocking’ at the door.

Her main focus in life at this point wasn’t work or education, but something else. ‘At the start of 1958,’ Gordon reports, ‘she weighed something between 13 and 15 stone; by that summer she had shrunk to around ten.’ She started smoking, and swearing, and falling out extravagantly with her increasingly invalid mother. She was into jazz and folk music and the sorts of film you could see at the NFT. And she was very much looking for a boyfriend, both for sex and as ‘the only possible release’ from home. Her search, however, ‘was considerably hampered by the fact that … my parents’ concern to protect me from predatory boys was only equalled by the enthusiasm with which the boys … protected themselves against me.’

And so the weight loss continued. ‘Attempted suicide by narcissism’, Carter called it in a review of Mara Selvini Palazzoli’s seminal book Self-Starvation 16 years later. ‘Clearly more was going on in my psyche than that, but sexual vanity was my justification.’ ‘Her mum kept trying to get her to eat cream buns and so on,’ Joan remembered. ‘She was terrified she would die.’ ‘It was,’ Carter concluded, ‘a difficult time, terminated, inevitably, by my early marriage as soon as I finally bumped into somebody who would go to Godard movies with me and on CND marches and even have sexual intercourse with me, although he insisted we should be engaged first.’ And so Angela married Paul Carter, an industrial chemist and weekend beatnik, and moved with him to Bristol in 1961. She applied for jobs with the Bristol Evening Post and BBC West but didn’t get them. Then she signed on with the Labour Exchange and started writing what her father, she claimed, always referred to as her ‘dirty books’.

There’s an amazing bit in Carter’s first fashion essay, ‘Notes towards a Theory of Sixties Style’ (1967), in which she fastens on the sorts of outfit worn by the Beatles on the cover of Sgt Pepper: ‘A guardsman in dress uniform is ostensibly an icon of aggression; his coat is as red as the blood he hopes to shed. Seen on a coat-hanger, with no man inside it, the uniform loses all its blustering significance and … becomes simply magnificent.’ Before the 1960s, khakis and camo, brass buttons and epaulettes, had to do with wars and warfare. After, you look back on all the stuff you’ve put babies and small children in, and you can’t believe you never thought about it, how the history of such cute adornments is wrapped up in the technology of mass death.

Imagining Carter in her first marriage involves a shift of similar magnitude. ‘I bought my first cookery book in 1960, as part of my trousseau,’ I remember her writing in an LRB piece in the 1980s; I was much impressed by both the glamour and the knowing ludicrousness of the vignette. Except that the humour, as I didn’t realise until much later, would have been an add-on. That ‘trousseau’ in 1960 was for real, and must quickly have accreted much unhappiness and pathos, being – as Carter knew, of course, by the time she wrote her essay – a totem of what became known in the 1960s as the feminine mystique.

She was never interested in what she called ‘the ephemeral pop mythology of the Beatles or miniskirts’. For her, ‘the vertigo of the 1960s’ was a profoundly serious matter, to do with Vietnam and Prague and Paris, when ‘the pleasure principle met the reality principle like an irresistible force encountering an immovable object,’ causing ‘reverberations’ that would echo for evermore. Paul went to work, organised concerts and recordings, started manifesting symptoms of depression. Angela cooked and cleaned as little as she could get away with – ‘It never ends, the buggering about with dirty dishes, coal pails, ash bins, shitbins’ – and worked away at her writing, ‘neurotically, compulsively’.

To begin with, she tried her hand at writing poetry. ‘Unicorn’, the star of the collection published by Rosemary Hill last year, first came out with a tiny press in 1963. A cardboard theatre and a vulgar virgin; a mythical beast with ‘little hooves’ that ‘click like false teeth’. At the age of 23, Carter had ‘arrived’, as Hill writes, ‘as it were in a single bound, in the middle of the mysterious forest that was to keep her supplied with ideas for the rest of her life’. She had begun studying English as a mature student at the University of Bristol; the course was liberatingly premodern in its focus, ‘out in the literary badlands’, as Hill puts it, ‘beyond the well-trodden path of Leavis’s Great Tradition’. Big girls, chimaeric emblems, rude jokes, the crudest allegory: all these bad-taste elements outlawed by Leavisism which Carter would go on to make her own were there in egg form from the very beginning.

And yet, when Carter started work on her first novel, she seemed to feel obliged to fit ‘everything she had’, as Gordon puts it, ‘dislikes and anxieties, her interest in clothes, music, Victorian bric-à-brac and provincial bohemia’, into the shape not of romance or fable, but a modish early 1960s novel of beatnik shenanigans in the heightened kitchen-sink mode of Shena Mackay and Shelagh Delaney, only nastier. She based her characters on people she knew from her local pub, so closely that her publisher required a letter of comfort from the man who supplied the model for the novel’s charismatic villain (whom the novel describes, at one point, as ‘ithyphallic’, the word cut, as Hill noticed, from ‘Unicorn’, to the poem’s advantage).

Shadow Dance (1966) tells the story of an ugly love triangle between cowardly Morris, beautiful Ghislaine and the dashing, psychopathic Honeybuzzard, with lots of dressing up and breaking in, casual sex and vicious cruelty, among the denizens of a pub described, the first time we enter it, as ‘a mock-up, a forgery, a fake’. Both men have slept with Ghislaine and either of them might be responsible for the ghastly knife wound now disfiguring her face, though Morris keeps telling us that Honeybuzzard was the perpetrator, ‘for doing what Morris had always wanted but never defined’. Ghislaine in any case is described as ‘rotten, phoney’. An old lady is ‘the Struldbrug’, her ‘sex ground down by the stubbed-out cigarettes of the years’. The inoffensive Emily has a ‘nigger-minstrel mouth’.

Shadow Dance, and the other so-called Bristol novels that followed it – Several Perceptions (1968), Love (1971) – capture the ugly underside of the 1960s fixation on beautiful young people, the hangers-on and the left-behinds, as David Widgery once put it, ‘who hung on to the myths and … ended up in a mess’. It’s spooky the way Carter describes Honeybuzzard, with his ‘soft, squashy-nosed, full-lipped face’, his ‘new, very white, very frilly shirt’, and Ghislaine, with her ‘long, yellow, milkmaid hair’: they could be Mick and Marianne. Spooky, but also static and stagey, humourless and histrionic. Carter wasn’t really interested in the plight of what Widgery called the ‘rank-and-file hippy’, but to begin with, she didn’t know how to write book-length fiction without them. She was going to have to work it out. ‘I might be bothered about, like, the nature of alienation and so on,’ she told an interviewer in 1976. ‘But these aren’t really the problems that my work presents to me – they are, how to get A out of a room so that B can come into it without them meeting. They’re constructional problems, grammatical problems, problems connected with imagery … Problems of tautness, of tension.’

And probably, a lot of what is most horrid in Carter’s early novels is so more or less by accident. Plots and metaphors and sentences twist and writhe and flicker so much because she can’t quite manage to work out what she wanted them to do in the first place: ‘In a metaphysical hinterland between intention and execution, someone had thrown a bottle in his face, a casual piece of violence; there was a dimension, surely, in the outer nebulae, maybe, where intentions were always executed, where even now he stumbled, bleeding, blinded.’ In the outer nebulae, maybe. ‘She might have been angling in her memory and brought up this small, spotted trout of a recollection.’ She might have been. This small, spotted trout.

In her journals, Carter kept trying to work out better ways of organising the worlds inside her fiction, looking for ways to show more clearly her sense of the fake and phoney, beauty and disfigurement, cruelty and domination, and so on. One step forward came in her second book, The Magic Toyshop (1967), which Gordon says is still her most widely read, whether because it’s so short, or because there really is something deep and true and powerful in the anxiety felt by the teenage Melanie, trapped in a house run by ‘these wild beings whose minds veered at crazy angles from the short, straight, smooth lines of her own experience’ and which Carter maybe was recalling from life.

‘The earliest stirrings,’ Gordon says, of The Magic Toyshop came from a phrase of André Breton’s, ‘the marvellous alone is beautiful,’ which Gordon says she wrote down ‘over and over again’. Carter’s notes for the novel show her growing interest in Surrealist automatic writing:

clockwork cat catching clockwork mouse

a dumb woman with red eyebrows

a toy theatre in which you take part

Surrealism flooded the kitchen sink in Carter’s fourth novel, Heroes and Villains (1969), a post-apocalyptic comic-strip picaresque which she described as ‘a juicy, overblown, exploding gothic lollipop’ and ‘an attempt to cross-fertilise Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Henri Rousseau’. The story of ‘spiteful’ Marianne, the professor’s daughter, who leaves her father’s ‘white tower’ to run off with the Barbarians, its plotline is much the same as that of The Magic Toyshop, but done in a wilder, more liminal way. ‘To begin with, she imagined the Barbarians as a biker gang, and read Hell’s Angels by Hunter S. Thompson,’ Gordon tells us. But then she became hugely absorbed by events in the world outside, in particular the événements in Paris, and upped the calibre of her reading to Lévi-Strauss and Adorno. ‘One felt one was living on the edge of the imaginable,’ she would write later. It started to feel like ‘living on a demolition site’.

In his 2011 preface to the novel, Carter’s friend Robert Coover quotes from one of her letters on the important point to grasp about her aspirations for her fiction, from Heroes and Villains on. She wanted, Coover writes, ‘a language that insisted upon itself as subject, “a fiction that takes full cognisance of its status as non-being – that is, a fiction that remains aware that it is of its own nature, which is a different nature than human, tactile immediacy. I really do believe” – Carter continued – “that a fiction absolutely self-conscious of itself as a different form of human experience than reality … can help to transform reality itself.”’

Her husband had started exhibiting ‘indrawn moods’ within a couple of months of their marriage. But ‘it’s conspicuous,’ Gordon writes, ‘that Paul’s first major depression coincided with [Angela] developing a life outside the home’ – he didn’t speak to her, Gordon writes, for three weeks after Shadow Dance was published. When Gordon approached Paul for an interview, he met with a ‘polite but very firm’ refusal. He died in 2011, without changing his mind. In August 1969, the Carters spent the prize money Angela had got for Several Perceptions (it won the Somerset Maugham Award) on a month-long road trip round America. Twelve years later, Angela published a story in which the narrator remembers ‘a decade ago now’ being in a bus station in Texas and choosing a peach from a vending machine. The ‘man I was then married to’ teased her, because of the two peaches available she had picked the smaller one; ‘I date my moral deterioration from this point.’ If the man hadn’t told her she was a fool to take the little peach, she writes, she never would have left him. ‘In truth he was, in a manner of speaking, always the little peach to me.’

Paul went home but Angela flew on to Tokyo, where she met the man who became her escape route from her marriage. In ‘A Souvenir of Japan’, which Gordon describes as ‘one of the most plangently beautiful things’ Carter ever wrote, she called him ‘Taro’ after Momotaro, or Peach Boy, a well-known Japanese tale. ‘He, too, had the inhuman sweetness of a child born from something other than a mother, a passive, cruel sweetness that I did not immediately understand, for it was that of the repressed masochism which, in my country, is usually confined to women.’

Carter never again allowed herself to become economically dependent on a man: ‘She wants, in fact, the kind of pretty, malleable man strong women often want,’ as she observed of George Eliot’s Dorothea in her essay ‘Alison’s Giggle’ (1983). And her lovers would mostly be younger than she was. Pearce was 19 and working as a builder when the 34-year-old Carter asked him over to help with a burst tap. ‘He came in and never left,’ she said. The relationship endured until her death.

Carter loved what she saw of Tokyo, ‘the most absolutely non-boring city in the world’, she called it, ‘like going through the looking-glass and finding out what kind of milk it is that looking-glass cats drink’. It was in a café in Shinjuku that she was picked up by a young man called Sozo Araki, who took her to a nearby love hotel. ‘He was plainly an object created in the mode of fantasy,’ she would write in one of the stories in Fireworks (1974). ‘His image was already present somewhere in my head, and I was seeking to discover it in actuality, looking at every face I met.’ This real-life Peach Boy was 24, a Waseda University dropout who had dreams of becoming a writer himself. Carter rounded off her holiday with a few days in Hong Kong and Bangkok, much of them spent in an enraptured first-time reading of Borges; back in the UK, she cut off Paul completely, had a quick fling with a close friend’s partner and made plans to return to Tokyo as soon as she could. Her mother died suddenly that December, unreconciled with the shameful daughter who had so ruthlessly wrecked her marriage. Carter spent the winter with her grieving father and went back to Tokyo the following spring.

The Japan section of Gordon’s book is very good, partly for the reasons Carter found her stay so liberating – so much to write about, and all of it ‘absolutely non-boring’ – but also because it rewards diligent footwork of the sort that Gordon does well. Carter’s adventures were well documented anyway, in her stories of the period and her pieces for New Society, and in the more than a thousand pages of letters she wrote from Tokyo to her great friend of the period, Carole Roffe. But Gordon has also followed the Carter trail round Japan, and re-enacted a trip she took in 1971 on the Trans-Siberian railway. And best of all, he has tracked down Sozo Araki, a ‘dapper’ 68 when Gordon met him, the author of books with titles such as Strategies for Love and Romance outside Marriage. He had pictures, Gordon tells us, of Elvis all round the toilet in his flat.

Carter must have realised quite quickly that Peach Boy was not the settling-down kind. In the evenings, while she worked, he went out bar-hopping, and playing pachinko, and picking up girls. But the relationship lasted over a wonderful winter in a rented beach-house near Chiba. Carter read Sade and worked on the book that became The Infernal Desire Machines of Dr Hoffman. ‘I didn’t get bored of just talking … and cooking and doing laundry,’ Araki told Gordon more than forty years later. ‘That was one of the happiest times of my life.’

Before Japan, Carter, being a big girl, seems to have struggled to feel herself sexually attractive. ‘A great, lumpy, butch cow,’ she wrote of herself, ‘titless and broadbeamed’; ‘a Russian female all-in wrestler’; ‘Britannia on the old penny coins’. In Japan, however, being English ‘was like saying I came from Atlantis, or that I was a unicorn’; ‘it is our size, our bigness, our fairness which drives them wild.’ In the hostess bar at which she worked – for all of a week – while researching a piece for New Society, Caucasian girls were paid more, and treated more respectfully, than Japanese hostesses. ‘I thought she was like a Hollywood actress, like Katharine Hepburn,’ Sozo said.

Carter was very upset indeed when Araki left her. Within a few months, however, she started a new relationship with an even younger man, a Korean called Mansu Ko, ‘who is, or rather was, a virgin; who is 19’ and who bought her a can of pineapple ‘because I seduced him’. Ko, as she always called him, was broken-hearted when Carter left him in 1972, when she decided it was time to go home for good, and his subsequent life, Gordon discovered, ‘hadn’t been pretty’. In 1991 he walked off the eighth floor of a building in Osaka. ‘He didn’t leave a note.’

In Fireworks, Carter writes with unusual directness about what Japan did to her: the liquidity and upheaval, the erotic and epistemological dismemberment, the exoticism and voyeurism and excitement of being gazed at as exotic herself. But the experience also went less obviously and more profoundly into the architecture of The Infernal Desire Machines of Dr Hoffman, her staggeringly strange and brilliant history of a world in which the pleasure and reality principles fight it out with each other to the death. The first time we meet Albertina, the narrator’s shape-shifting, impossible love object, she comes as a man with high cheekbones, ‘vestigial’ eyelids and ‘luxuriantly glossy hair so black it was purplish in colour’ – ‘the most beautiful human being I had ever seen’. The language of the river people the narrator spends time with has no plurals, universals or copula, and when they drink, tradition dictates that they may only pour out for neighbours, not themselves. But mostly, the influence of Japan was less obviously magic-tourist, more diffuse.

Carter’s next novel, The Passion of New Eve (1977), was the first fiction of hers I read. I missed out, I’m sad to learn from Nicole Ward Jouve’s essay, on the old Pan paperback edition, ‘with a black-booted, fishnet-stockinged blonde on the cover, complete with whip’. It’s worth looking on the internet to see the way Carter was marketed before she, and publishing in general, were ‘comprehensively Virago-ed’, to borrow her friend Christopher Frayling’s not entirely approving phrase. A 1976 edition of Fireworks has a naked white man clutching at the breast of a naked black woman, the woman chained by the throat to the man’s spiky helmet. She also has what looks like a yellow octopus sitting on her head.

Carter had originally planned to make The Infernal Desire Machines of Dr Hoffman the first in a surreal-allegorical trilogy, with the second part to be called ‘The Great Hermaphrodite’. But the title morphed, as did the story, and it hasn’t stopped morphing even now. I was, I remember, utterly floored by The Passion of New Eve: a man called Evelyn, who is given a forced sex change. A cosmetic surgeon called Mother, ‘her head … as big and as black as Marx’s head in Highgate Cemetery’, and ‘breasted’ with two rows of nipples, ‘like a sow’. A reclusive, Garbo-like screen goddess called Tristessa, who turns out to be a man … It was all too much for me and I thought I hadn’t made head nor tail of it. I read it again a couple of weeks ago and it was as though the figures had been sitting in my head for decades, but I hadn’t been looking properly. One shake and they beautifully resolved themselves, with the silliness and clarity of a dream.

The Passion of New Eve, Sage thinks, is ‘an allegory of the painful process by which the 1970s women’s movement had had to carve its own identity from the unisex mould of 1960s radical politics’; which is to say, it was an allegory of Carter’s own ‘“coming out” as a feminist … though she had been one in a sense all along.’ She started contributing to Spare Rib in 1973, and was working on The Sadeian Woman for Virago from 1975. ‘You knew Angela Carter before she was Angela Carter,’ Frayling records Marina Warner saying to him in the memoir he has written about the Angela he knew in Bath. ‘I don’t actually think that is right. She was Angela Carter all right … She was already well into wings and swans and metamorphoses.’

So many of the friends Carter made on her return to Britain have themselves become so famous that the later parts of Gordon’s book can’t help but get a bit luvvie-ish: Carmen and Deborah and Liz and Lorna and Salman (though it’s nice that Gordon puts in the spiteful way Carter referred to Ian McEwan behind his back as ‘poor Ian’, as in, ‘poor Ian has been dreadfully overrated’ – she was always chippy about what she saw, with perfect accuracy, as her own relative lack of reward and recognition, in comparison to that of certain men). She sat as a Booker judge – she was the one Selina Scott disgraced herself by failing to recognise – and took residences at Sheffield, UEA, Brown, UT Austin, Adelaide.

Rick Moody remembered his first encounter with Carter at a creative writing seminar: ‘Some young guy in the back … raised his hand and, with a sort of withering scepticism, asked, “Well, what’s your work like?” … There were a lot of ums and ahs … Then she said, “My work cuts like a steel blade at the base of a man’s penis.”’ She was, Rushdie remembers, the favourite among his friends with the police officers charged with his protection during the fatwa against The Satanic Verses. ‘She always made sure that they had a good meal, and were taken care of, and had a TV to watch.’

Gordon acknowledges that readers may be disappointed that the first Carter biography has been written by a man. He worked, presumably, with Carter’s own remarks about Anthony Alpers, the ‘gallant male biographer’ of Katharine Mansfield, ringing in his ears, and has been careful to avoid what Carter called Alpers’s ‘prurient intimacy of tone’, as if ‘conducting a posthumous affair’. He’s polite and respectful and extremely thorough, and his good manners extend particularly to sources who suffered from Carter’s self-protective brusqueness. One of the first things she did, for example, when she came back from Japan was to fall out with Carole Roffe, her beloved correspondent of the 1960s. Roffe died while Gordon was working on his book, he says, never really understanding why.

When Carter wrote about the Mansfield biography, she reserved particular scorn for Alpers’s ‘gynaecologically exhaustive’ method of tracking his subject’s menstrual cycle. At several points in her life, at times of transition and enormous stress, Carter experienced what she thought of, and Gordon concurs in identifying as, phantom pregnancies. Very sensibly, he doesn’t make a fuss of them, just marks the places out. Ditto Carter’s occasional recourse to prescription tranquillisers (other than which there’s no suggestion that she did drugs – her 1960s was about a more profound sort of revolution in the head). And at a few points Gordon lets his subject be seen indulging in romantic cruelty and sadistic fantasy: Mansu Ko as ‘sexual bric-à-brac’; of the wife of an early lover, ‘I wish Jenny would try to kill herself.’ She stuck a picture over the page in her journal where she wrote that, Gordon says, but it became unstuck.

Gordon’s book lacks a bit in critical excitement and intellectual hinterland. I haven’t made the close study of the Carter papers that he has, but it seems likely that from her A-level years onwards, Carter spent huge amounts of her time reading and thinking with French writers, and that this is one reason she was so shaken by the events of 1968. That postwar encounter with Surrealists and poststructuralists was, as Sage writes, part of ‘a generation’s collective life story’ and Gordon could have made a lot more of it. I was interested, however, to learn that much of The Sadeian Woman may have roots in Surréalisme et sexualité by Xavière Gauthier (1971), which Marion Boyars commissioned Carter to translate into English then rejected – no English translation of the book has yet appeared, although the Swedish scholar Anna Watz has one in preparation, and has a chapter on the connection in her recently published Angela Carter and Surrealism: A Feminist Libertarian Aesthetic. And Gordon further edges into the territory with a short, odd paragraph on Barthes: ‘She went out of her way to throw commentators off the scent of his influence (in 1978 she told an interviewer that “I’ve only just read Barthes. Last month”) … In 1976 she wrote a piece about wrestling … very like Barthes’s take on the subject 20 years earlier in Mythologies.’ The echoes are ‘too soft to count as plagiarism’, Gordon considers, ‘but neither can they be entirely coincidental’.

A historian’s life , Rosemary Hill wrote in her preface to Unicorn, is spent looking backwards, and the same is true of a book reviewer. ‘And inevitably there comes a moment when, as in the rearview mirror as it were, you glimpse a familiar figure who is your younger self passing into history’ – it simply happens, when writing about times and figures who are, as Hill says, still ‘on the cusp of living memory’, that one’s relationship with one’s material becomes ‘semi-detached’. And not like a house, more like a hangnail. It’s not just what you think you see in the material you’re dealing with, but actual bits of yourself.

Coincidentally, one of the little stories Gordon puts in his own preface illustrates Hill’s point perfectly, and all the more so for being tremendously sad and painful. I was too late ever to have met Carter or even to have seen her from the other side of a room, but I was a big fan and I remember reading one tribute in particular in the days after she died. It was by the Guardian’s Veronica Horwell and it was about how, although she wasn’t a friend of Carter’s, she used to relish running into her in Clapham:

Carter queuing in the post office then missing her turn, apparently bemused by video commercials for collectable commemorative issues; Carter encountering an unaccompanied barking Alsatian by the war memorial – the dog backed off; Carter and Alex at the window of the fancy new shop that sold Latin American ornaments. ‘Look at that snake at the back,’ she said. A countable pause. ‘Their devils are dull.’

One morning, Horwell continued, ‘after she must have known about her cancer, I found her smoking cigarettes in a bad-prefect-behind-the-bike-shed way on the seat by the Underground … “Much wilder than Tokyo,” she said, and lit another wicked ciggie from the butt of the last.’ In the next day’s Guardian, a letter appeared from one of Carter’s friends, written on behalf of Pearce and others. ‘Did Angela live in the world of Horwell’s fantasies rather than the streets of Clapham? … Angela gave up smoking about ten years ago … She was much too honest a person to pretend.’

A few years later, I got to know Horwell as a colleague, though I never asked her about this incident – I couldn’t have done, it would have been terrible. Imagine writing such a lovely, affectionate tribute, and then it going so wrong. I wouldn’t bring it up now, except that Gordon has, right at the beginning of his book, taking from it the message that fantasy ‘has a habit of corrupting memory’, and that biographers need always to bear this in mind. So I emailed Horwell and asked her what she made of that incident now. ‘I don’t know,’ she said, ‘except that I’ve avoided writing personal pieces ever since, unless I could produce backup evidence from notebooks or letters or emails.’ No one now can ever vindicate or refute her, not that there would be any point.

Carter is smoking in four of the photos that illustrate Gordon’s biography, though not in any taken when she would have been over forty. And Carmen Callil is smoking in one. And so is Lorna Sage. It’s strange that smoking doesn’t feature more in Gordon’s biography: it was a force, a practice, a terrible delusion, that shaped and defined that generation of women, among all the other practices and delusions that get written about all the time. Gordon ends his book by inviting his successors to start working on another one, ‘from a completely different perspective’. It’s not just Carter but that whole group of limitlessly free, inquiringly rootless women that are as Gordon puts it ‘too big for any single book to contain’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.