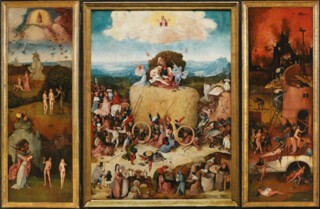

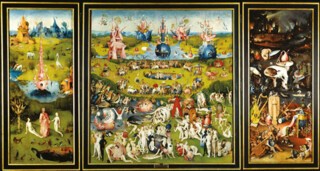

Hieronymus Bosch had a unique facility for depicting on wood and canvas the combination of corruption and innocence that characterises us. Bosch’s abysses, like our own, are inhabited by hybrid monsters, creatures half-angel, half-beast, and make us wonder which half will pounce on the other and enslave it. His visions anticipate Rabelais’s phantasmagoria. But unlike Francesco Colonna’s The Dream of Poliphilus, written in Bosch’s time but published only later, unlike even the Park of Monsters in Bomarzo, Bosch’s work does not invite transient moments of contemplation. As the fruit of a heightened consciousness that scrutinised the secret universe of subjectivity, it puts us in the dock and demands that we cross-examine ourselves. Nightmare and reverie in Bosch go beyond a ‘picture of the state of things’ meant to elicit admiration or repulsion, beyond moral judgment, and beyond the kind of intellectual speculation that is no more than substance disincarnate, thought detached from life. What confronts us is a mirror of what dwells within, haunting us, possessing us, casting a spell and obscurely governing our actions. We find ourselves, standing in front of Bosch’s paintings, suddenly obliged to engage with the traces of humanity and inhumanity that intermingle and do battle within us. The question arises: what possible human faculty might be called on to bring calm and harmony to inner chaos? Not a faculty of judgment – of approval or condemnation – since in Bosch there is no aspect of the self that is unaccompanied by its opposite; the torments of hell go hand in hand with the delights of the Golden Age.

The basic instinctual paraphernalia of the inner self does seem, whatever the particular rationality, normality or spiritual cult beneath which it is concealed, to traverse the history of humanity relatively unchanged. (Is it not tempting to speak of an ‘ahistorical’ psyche when one realises how little difference there is between the contemporaries of Gilgamesh and the militarised brutes, the fanatics, the exploiters and the exploited of the 21st century?) But with Bosch, no doubt, the particular manifestation of that self, its mobilisation and its pictorial representation, do belong to the historical period and social circumstances of his everyday life.

He was obviously a man of erudition, a scholar with a wide-ranging curiosity. Attention has often been drawn to the frequent presence in his work of the sort of colporteur who criss-crossed national boundaries at that time, peddling almanacs, prayer books, banned lampoons and booklets whose edifying covers disguised ideas hostile to established orthodoxies and authorities. Bosch was also highly respected, a notable, a guildsman and a member of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady in ’s-Hertogenbosch. If that is surprising it is because we are too prone to underestimate the degree to which the dominance of the Inquisition, with its accompanying theology of repression, the tyranny of governments both civil and ecclesiastical, and more pervasively the pressure of custom and prejudice, led some men and women into a clandestine second existence where they took on roles proscribed by the conformism around them. There they indulged the pleasures of the flesh, preached hedonism, and engaged in extortion, crime and subversion – all the while planning to obtain forgiveness for their sins by way of last-minute penitence. It is not implausible to suppose that Bosch had such a double life; to imagine in him a willingness to break free of the roles that society expects its members to play, and a wish to reveal, with a kind of malicious innocence, what seethes underneath a cassock or a uniform, or behind the masks of virtue, clear conscience or good manners.

We know that Bosch was acquainted with a man named Jacob Van Almaegien. Van Almaegien was a Jew who converted to Christianity perhaps more out of convenience than conviction, since, according to the Bosch scholar Wilhelm Fraenger, after being admitted to the Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady he returned to Judaism. If Bosch shows more fascination with the Jews than animosity towards them – his images of Jewish greed share in the anti-Semitism of the day, but one is struck by the loving exactitude of his portrayal of objects and rituals indicating the Jewish origins of Christianity – it may well be because of his friendship with Van Almaegien. He appears to have been very knowledgeable about the Jewish gnosticism from which early Christianity arose. That doesn’t necessarily mean he was an adept of the radical heretical Movement of the Free Spirit, which from the 13th to the 17th century was mercilessly repressed throughout Europe. But there is nothing untoward in the idea that he might have belonged to a subversive sect. At the turn of the 15th century, such artists as Grünewald, Holbein, Dürer, Altdorfer, the Behaim brothers, Jörg Ratgeb and Riemenschneider supported the peasants of the Bundschuh movement in their war against Lutheran orthodoxy and Luther’s princely allies. Pieter Bruegel, a great admirer of Bosch, may have belonged in his youth in Antwerp to the Family of Love, founded by Hendrik Niclaes, who was accused of promoting the right to let the passions express themselves, free from constraint, fear and guilt.

In 1411 in Brussels, the Inquisition intervened against the sect known as the Homines Intelligentiae, which preached and practised the freedom to love in a rediscovered Edenic innocence. The group’s meetings took place in a tower belonging to a city alderman. Under the supervision of two friars, Willem Van Hildernissen and Gilles De Canter, common people and patricians rallied to repudiate the authority of the church and its dogma. They held that, since God was within every human being, men and women were entitled to exercise natural freedoms without reservations, without being accountable to anyone. According to them, the doctrine of sin was no more than a way for the Church to tighten its grip. Although the charge sheet evoked orgy and fornication, the group’s real interest was in debating love, focusing on the issues of chastity and carnal relations – all this less in the courtly spirit of the 12th and 13th centuries than in the belief that a new society was being constructed that would promote a return to primal innocence. The repression of the movement – effective but relatively moderate, probably on account of its great mass of devotees and the eminent figures suspected of being members – led to its scattering.

Bohemia, where the Taborites of Jan Žižka were burning churches and monasteries and preaching egalitarianism, received a sudden influx of Homines Intelligentiae, who, having escaped their persecutors, wanted to spread their ideas in regions presumably more hospitable to them. Known as Picarti (Picards), they joined forces in the vicinity of Prague with the most extreme Taborite groups, provoking the schism that produced the so-called Adamites. The Adamites established small libertarian communities that held their possessions in common, practised free love, and celebrated Edenic innocence by going naked. Žižka very soon realised that the Adamites were a threat to the absolute authority he had acquired thanks to his assaults on Catholics and moderate Hussites. In 1421 he launched a campaign to exterminate the Adamites that made liberal use of torture and the stake. What seems to have escaped Fraenger is that those Adamites who avoided the massacre returned to their native areas and swarmed into the Low Countries, where their influence became apparent some decades after the Bohemian episode.

The red thread from the Free Spirit and the Adamites continued unbroken. Between 1417 and 1431, Pope Martin V addressed three bulls to the Bishop of Tournai congratulating him on the elimination of dangerous arch-heretics. Notable among these was Gilles Meursault, who, after returning from Prague, distributed incendiary pamphlets in 1423 directed against the Church, denouncing evangelical pseudo-truths. His arrest provoked a popular uprising that rescued him from the stake. He fell into the clutches of the Inquisition, however, and was executed. In 1429 one of his disciples, Jacquemart de Bleharies, went to the stake, followed by Willemme Dubos and Olivier Deledeulle. In subsequent years there was a great increase in the number of executions of people the Church dubbed ‘Hussites’, but who were mostly survivors of Žižka’s massacres.

The underground activity of the Adamites in the northern Low Countries could not have escaped Bosch’s attention. In the 1490s the scholar Herman de Rijswijck circulated clandestine pamphlets defending atheism, mocking evangelical mumbo-jumbo, rejecting the idea of sin and proclaiming the innocence of a life freed from the yoke of ‘Christian stupidity’. He was thrown in prison, managed to escape, but a second arrest sealed his fate: in December 1512 he was burned at the stake in The Hague, along with his writings. Not long afterwards the Anabaptists emerged, with their ideas of equality, rejection of the obligatory baptism of infants, common ownership of goods, and again the dream of an Eden on earth. Yet this idyllic vision led to bloody tyranny in Münster, where John of Leiden massacred his friends and partisans before being put to death himself.

Bosch displays a deep acquaintance with alchemy, witchcraft, Hebraism, gnosticism, hallucinogenic mushrooms and popular folklore. His paintings are replete with graphic representations of riddles, puns and plays on words based on bawdy allusions. How much did Bosch know of the internal history of the underground sects? Did he realise that the Adamites had provided the pretext for their bloody repression by Žižka? Isolated and withdrawn, their communities had gradually turned to plunder and marauding. Žižka’s wish, meanwhile, was to eradicate their dream of a paradisial society. By resorting to predatory behaviour, the Adamites gave him an excuse to destroy them. But what difference does it really make how far Bosch understood the dialectics of heresy? What he drew on most deeply was his own chaotic subjectivity, and there he found images of the conflict that goes on making and unmaking our very sense of the human, pushing ‘humanity’ back to its wild beginnings. Isn’t Bosch’s ‘man’ the locus of a cosmic and microcosmic war, in which Nature and Against Nature are involved in an unending fight to the death? Human beings are obliged to struggle incessantly against the antiphysis of a system of exploitation of man by man, relayed by religion and ideology, which each individual has internalised.

We escape too rarely from the grip of dualism. Dualism is a hell of which heaven is a part. We have forever been confronted by an agonising reality, the vicissitudes of a good and evil that are strictly interchangeable. A reality organised and patched up for centuries by a worldwide culture in which imbecility trumps intelligence and universalising thought mulls interminably over platitudes: le mort saisit le vif; after the rain comes the sunshine; everything becomes wearisome, everything breaks; six of one and half a dozen of the other; the wheel of fortune revolves around a void. Each of us is driven to the edge of a swamp where there is no choice but to plunge in and drift in a state of nausea for a lifetime before drowning.

What the puritan sees in Bosch’s pictures is the horror of sin. The pious and bloodthirsty Philip II of Spain, a great lover of Bosch, discovered an image of the rift in himself between the lust that tormented him beneath his hair shirt and the ferocious chastisement of Eros that he practised by burning a good many of his subjects at the stake. As for hedonists, transgressors of taboos, they find gratification after the fashion of Sade. They believe they are wringing the neck of sin, but what they really experience is a twisted, strangled, fraught sort of pleasure, a passion distorted by predatory impulses. Their libertinism is practised only by means of ruse and force (much like the art of war). Is this not what Bosch is denouncing when he depicts a nun with a trout’s body who demands a donation or an act of obedience from her frightened lover as the price of her kisses?

What are we to make of this monstrous bird that gobbles up men and women and adds to the legions of the damned by expelling them in an egg-shaped cloud of flatus? Is this the Devil devouring sinners? Or is it the Church, exposed as the real purveyor of hell, converting the energy of life into lust, and love into fornication? Something of both, most likely. The Garden of Earthly Delights depicts the transcendent duality that tortures man on the wheel of fortune and misfortune, placing happiness under the yoke of transience, fear and guilt. No other painter has offered such a sensitive vision of a society where the inclinations of each harmonise with the desires of all. No other painter belongs so completely to the lineage of Rabelais, Hölderlin and Fourier.

No resonance is serendipitous, and none should be overlooked among the echoes to be heard between beings, things, words and sounds. The ethologist Frans de Waal, who was born in ’s-Hertogenbosch, describes in his book The Bonobo and the Atheist (2013) a society of evolved primates in which free love, solidarity, the art of sensual pleasure, the status of women, and the absence of violence and aggression prefigure the way of life of hunter-gatherers prior to the agrarian revolution and the rise of city-states. Is this not the picture painted in a poetic mode by The Garden of Earthly Delights, where, to quote one of Bosch’s great admirers, ‘people play a thousand erotic games while savouring giant berries and strawberries in the midst of giant birds; the whole scene is imbued with an indescribable grace, fresh as the first morning, with not the slightest shadow of guilt in an atmosphere of completely unheard-of innocence’? Despite the spectacle of everyday horror sustained by the media’s lies, are we not on the point of reconnecting with the evolutionary process due to overwhelm our present state of survival, which is a social jungle where the laws of predation hold sway and make our existence ever more unliveable?

The fact that Bosch was, historically speaking, a premature Renaissance man also marks him out as the alchemist of an ongoing mutation. He belongs to the tradition of those who, by peering deeply and without indulgence into themselves, have obstinately advanced the excavation of our desperately inhuman history. The dream of a society where life triumphs over the contempt visited on us by the rule of the commodity is not an illusory restoration of some golden age, but instead the way out of the nightmare that chokes us ever more tightly each day. Bosch’s contribution is to have held up a looking-glass to our anguish as well as to our irrepressible will to live. A looking-glass that we must pass through if we are to make our way beyond the realities it reflects.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.