‘Could anything be better than to start off with a fine picture of a sailing ship on the rough sea coming suddenly alive and sucking in the children?’ Stevie Smith asked, reviewing C.S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader in 1952. She liked depictions of people who disappeared into the objects of their gaze; a couple of years earlier, her poem ‘Deeply Morbid’ told the story of Joan, an office girl who goes to the National Gallery during her lunchbreaks and studies Turner’s seascapes until ‘the spray reached out and sucked her in.’ Elsewhere she wrote that the ‘dangerous swift current’ of Canaletto’s Venice drew her through the picture-glass, out past the gondolas and towards the open sea:

Is this escape-into-the-frame a fine game for a hot afternoon, or is it rather something that conceals itself beneath a frivolity? To be isolated for ever in some romantic and forlorn landscape, enchanted oneself and imprisoned ‘out of time’, beyond the necessities of human life, their humilities and importunities, without hope, without hope of return, without the aggravating possibility of some knight-errantry, how delicious, when one is in the mood, the contemplation of such a fate.

This is characteristic of Smith’s hard-edged daydreaming: the intensity of the imagined flight from ‘the necessities of human life’ is a confession of the seductive power of the necessities themselves. Even as she slips from the hot afternoon into the coolness of the sea, you sense that an absorption into a ‘romantic and forlorn’ landscape isn’t really an escape from longing; her slight qualification – ‘without hope, without hope of return’ – may imply that, even in glorious isolation, certain hopes persist. And besides, what is being relished here is the contemplation of such a fate, not necessarily the fate itself. Delicious, no doubt, but only when one is in the mood.

In The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, the ship’s prow is ‘gilded and shaped like the head of a dragon with wide open mouth’, so when, a moment later, the children stare at the picture ‘with open mouths’, they are being remade in its image – or perhaps what they stare at is a version of their own hunger for adventure. The painted ocean to which Joan is drawn is ‘like a mighty animal’, a ‘wicked virile thing’. The implication in both cases is that art is not safe, and that this is why it’s needed. Many others are led towards Leviathan, or towards a watery grave, in Smith’s writing: the girl-soldier Vaudevue rushes to the icy embrace of ‘the adorable lake’, ‘Her mind is as secret from her/As the water on which she swims.’ It’s worth emphasising the inscrutable, untamed nature of such encounters because Smith’s admirers often treat her as something of a pet. Although Larkin’s review of Selected Poems in 1962 drew attention to her achievement, he called her drawings ‘cute’ while noting that some of her phrases, though not ‘full-scale’ poems, hung around in one’s mind ‘long after one has put the book down in favour of Wallace Stevens’. And then there was her interest in pets: ‘She has also written a book about cats, which as far as I am concerned casts a shadow over even the most illustrious name.’ Although the unillustrious poet privately acknowledged her debt to the review, she noted Larkin’s unease, ‘hence his shifting around a bit and coming out with the old charge of fausse-naïveté!’

Reviewing her again ten years later, just after her death in 1971 at the age of 68, Larkin asked: ‘Did she, truly, not develop? Unless one has all the books, it’s hard to be specific (a Collected Poems as soon as possible, please).’ James MacGibbon’s edition followed in 1975, but it has now been out of print for twenty years. Seamus Heaney reviewed it appreciatively but apologetically: ‘Yet finally the voice, the style, the literary resources are not adequate to the sombre recognitions,’ he claimed. ‘There is a retreat from resonance, as if the spirit of A.A. Milne successfully vied with the spirit of Emily Dickinson.’ Reading Will May’s capacious new edition, I didn’t detect any such retreat. Some of Smith’s best poems are the fantastical, slightly longer ones like ‘The Blue from Heaven’, ‘Fafnir and the Knights’, ‘The Frozen Lake’, ‘The Frog Prince’ and ‘The Ass’: the strange stateliness of their pacing, their weird combinations of the wishful and the inexorable, need time to work their effects. Smith’s reputation as a quirky miniaturist often preceded her; like others before and since, Heaney pointed to the smaller poems’ debts to clerihew and caricature, and felt that ‘large orchestration’ was in short supply. A few years later Amy Clampitt paid homage while also suggesting that ‘perhaps one day Stevie Smith will be seen as having to some degree paved the way for a body of work whose upper register is distinguished by a spaciousness and clarity hers never achieved.’

The idea that Smith didn’t develop is a dull one regardless of whether it’s true or false (as John Bayley pointed out: ‘She never needed to do anything so banal as to “develop”, for the spectrum of tone continuously present is amazingly wide’). Despite his earlier criticism of her interest in cats Larkin’s later review singled out ‘The Singing Cat’ as one of her most moving poems. It is – partly because of its jubilant insistence on what the animal may speak to in the human animals that watch over him, and partly because of the feeling the poem gives that the cat can never quite be spoken for. When asked in an interview if she ever managed to get herself ‘out of the way’ in her work, Smith replied: ‘The poem can claim to be about a cat but it’s really about you yourself.’ Not that this necessarily clarifies things; in her introduction to the book Larkin alluded to (Cats in Colour), Smith had observed that animal life is ‘too dark for us to read’. Even our pets are not ours, and – if we still insist on condescending to them – ‘out come the beautiful claws; our pet is not unarmed.’ Both sphinx and savage, the pet is an escape artist who has mixed feelings about her patrons. ‘Art is wild as a cat and quite separate from civilisation,’ Smith wrote elsewhere. She was not unduly concerned about what civilisation thought of her, although the voices in her poems often show just how much intimacy lies crouching in animosity: ‘I prowl about at night/And what most I love I bite.’

Pets, for Smith, always brought with them the ghost of a primal scene that was both a temptation and a trap. In her essay ‘What Poems Are Made of’ she admitted she was ‘haunted by the fear of what might have happened if I had not been able to draw back in time from the husband-wives-children and pet animals situation in which I surely should have failed’. Her sense of what might have been was informed by what had already taken place. When the novelist Kay Dick asked her for a brief biography in 1953 (she seems to have been planning a piece on Smith), Smith replied: ‘It is precious dull I must say, unless we dip into fic. One might say for instance, Born in Afghanistan by accident on a picnic etc. But the truth is, born in Hull, came south at the age of 4, lived ever since in London.’ She doesn’t mention the reason she came south: when she was three her father, Charles, left and the family was forced to uproot. Her parents had not been happily married; Charles had wanted to be a sailor since he’d been a child but had been pressured by his mother to take over the family business. It went bust and he sailed away, visiting sporadically over the next few years and sometimes sending brief messages to his daughters from abroad. Smith felt more able to tell the story when she dipped into fiction; in Novel on Yellow Paper (1936) her alter ego, Pompey Casmilus, remembers one of his postcards: ‘“Off to Valparaiso love Daddy.” And a very profound impression of transiency they left upon me.’ Charles was charismatic, absent-minded, wayward (‘could charm the birds off the trees’, Smith’s aunt recalled, ‘couldn’t pass a pub’). Smith wasn’t entirely charmed: ‘When I saw the suffering of my much loved ma, I raged against my absconding and very absent pa.’ In ‘Papa Love Baby’ she mocks the idea that ‘daughters are always supposed to be/In love with papa,’ explains that ‘I couldn’t take to him at all/But he took to me,’ and ends:

I sat upright in my baby carriage

And wished mama hadn’t made such a foolish marriage.

I tried to hide it, but it showed in my eyes unfortunately

And a fortnight later papa ran away to sea.He used to come home on leave

It was always the same

I could not grieve

But I think I was somewhat to blame.

The lines may allow for fausse-naïveté, but one of the most disarming things about Smith’s writing is her feeling for just how close the naive can get to the truth. The poem has a pared-down Jamesian quality – call it ‘What Stevie Knew’. In her astonishing twist on The Turn of the Screw, when Smith has Miles say of his governess, ‘She made me feel/A hundred years more old than I was, than she was,’ it’s the last phrase that chills. Although an adult might seek to condescend to these children – and these poems – by describing them as ‘precocious’, the word doesn’t offer protection from such uncanny creatures.

Smith once referred to ‘a child’s power of fetching what it wants’, but many of the poems contain wish-fulfilments that aren’t wholly fulfilling. ‘Papa Love Baby’ has her distinctive blend of the laconic and the chronic; a line like ‘I could not grieve’ is matter of fact, nonchalant, yet also stuck, impotent. And then there’s that strange connection between father and daughter: she ‘tried to hide’ and he ‘ran away’. It takes one to know one, and, as Smith admitted of herself elsewhere, ‘guilt runs with tiredness and a sort of farewell mood too, a desire to go, at all costs to go.’ One of her earliest passions was another guilty sailor – she loved ‘The Ancient Mariner’, loved ‘tasting the salt on my blackened lips … panting for rain’ – and in an excised passage from The Holiday (the novel Smith published in 1949, the year after her father died) the protagonist admits: ‘There is the sea, and one wishes to get into it, but there are always so many things to do.’ It might be said that she blamed herself (‘somewhat’) for what her mother’s life had become, or that she made up for her mother’s life by endlessly desiring and thinking of her father’s: ‘In my dreams I am always saying goodbye and riding away.’

Somebody who is ‘always’ saying goodbye never quite goes away. In Smith’s novel Over the Frontier (1938), Celia pauses to note that ‘To say goodbye at one swoop to things hated and things loved (work it out for yourself) is a happiness and a turn of fate unlooked for by me.’ Smith’s appetite for adieux is fed by a memory of the times she was forced to say goodbye; leave-taking becomes a way of avoiding – or answering back to – the possibility that she might be left. Her comment to Kay Dick that, once she moved south, she’d ‘lived ever since in London’ wasn’t true. At the age of five, Smith contracted TB and spent three years at a convalescent home in Kent. Novel on Yellow Paper speaks of the horror of her time there, ‘where I was so proud and so furious to be separated from my mother I would not eat’. ‘I actually thought of suicide for the first time when I was eight,’ she recalled in an interview in 1965. ‘The thought cheered me up wonderfully and quite saved my life. For if one can remove oneself at any time from the world, why particularly now?’

Smith’s poems find various ways to restage that question. Her writing marries the orphanic with the orphic; traumatic exposure or isolation is translated into an occasion for self-making or shady pleasure. Smith’s mother died from heart disease in 1919 when she was 16. ‘The last minute when you are dying, that may be a very long time indeed,’ Pompey writes in Novel on Yellow Paper. ‘So now it is all over, it is all over and she is dead. Yes it is all over, it is all over, it is.’ It is never over in the poems. Smith rhymes ‘mother’ both with ‘smother’ and with ‘other’; the mother is always too close or too far away – too close because too far away. Yet separation brings with it a secret, vertiginous thrill. In ‘Persephone’, the goddess hears her mother calling for her, but the daughter wants to stay in the underworld and the poem ends:

I in my new land learning

Snow-drifts on the fingers burning.

Ice, hurricane, cry: No returning.Does my husband the King know, does he guess

In this wintriness

Is my happiness?

Much has been made of her weary longings for death, yet in Novel on Yellow Paper Pompey suspects that ‘we shall spend eternity wishing we could set eyes on Aunt Martha’s old fur cape.’ ‘I love life. I adore it,’ Smith confessed to Dick, ‘but only because I keep myself well on the edge.’ Being on the edge of things brings the things themselves – and the person who gazes on them – to life. In ‘The River Deben’ she rows in a boat with Death:

But the oars dip I am rowing they dip and scatter

The phosphorescence in a sudden spatter

Of light that is more actual than a piece of matter.

It’s a passing out of the material world that brings the world back with a vengeance. Somewhere behind this moment is the Ancient Mariner’s shocked delight at the beauty of the water-snakes in moonlight, ‘the elfish light’ that ‘fell off in hoary flakes’. Smith never forgot the passage, recalled ‘seeing for ever and ever the sea creatures twining for their pleasure. It was their inhumanity I loved.’ Looking at things offers consolation as a form of attention and feeling that is neither solicitous nor callous. ‘Saint Anthony and the Rose of Life’ contains an ecstasy of observation:

A strapping life heavy and bright

Bulged in the rose and her leaves

And up from the roots of the substantial plant

The bold drops ran like thieves.

In the Life of Anthony by Athanasius, such blandishments are the devil’s work. For all Smith’s preserved, vigilant distances, though, writing like this doesn’t champion asceticism. The self-possessed, brimming life of the thing – the way each line springs a new metrical surprise even as the shape holds itself together – is an education in the dark arts of arousal. The simile comes from nowhere, but it comes with what Smith elsewhere described as ‘the madness and correctitude of poetry’. Those thieves – like the flower and the poem they feed – are in league with stolen, fleeting pleasures.

Smith is the poet of ‘bold drops’. Robert Lowell was enthusiastic about her writing because it was ‘so unlike the usual poem trying so hard to be a poem’. In her essay ‘Simply Living’, she refers to ‘the pleasures of simplicity’ in order to make a fine distinction. ‘Enjoyment lurks in simplicity. “Lurks” is the word, I think. You do not seek enjoyment, it swims up to you.’ A poet who is willing to appear slight or light, willing to use words like ‘Phew’ or ‘ahem’ in her first collection, is going to have to swim against the tide of what certain readers take poetic enjoyment to be. Yet, for Smith, simplicity is something you get to rather than something you settle for; the simple is the essence, not the opposite, of the complex. (In her essays she praises Ronald Knox’s sermons for their ‘achieved simplicity’ and the Grimm Brothers’ fairy tales for the ‘play of imagination in their simplicity’.) Muriel Rukeyser called her ‘our acrobat of simplicity’, which nicely captures the daring of her high-wire acts with the normal and the normative:

With my looks I am bound to look simple or fast I would rather look simple

So I wear a tall hat on the back of my head that is rather a temple

And I walk rather queerly and comb my long hair

And people say, Don’t bother about her.

So in my time I have picked up a good many facts,

Rather more than the people do who wear smart hats

And I do not deceive because I am rather simple too

And although I collect facts I do not always know what they amount to.

This is so delightfully fast that one is wary of slowing it down. If you do, though, you start to sense just how quick-witted the apparently simple can be. ‘Rather’ simple? The word is not trying to deceive, exactly, but given that ‘rather’ takes slightly different meanings in four of the previous six lines, there is an invitation to read it in more ways than one. The dust-jacket blurb (very likely written by Smith herself) for the volume in which these lines first appeared explained that ‘When the author reads her poetry on air … it is noticeable that the stress does not always fall where it appears to.’ The poem’s rather queer rhythmical walk could allow for strong, apparently straight-talking stresses on ‘do’ and ‘am’ in the penultimate line above (as if to say: ‘I do have to concede, I am rather simple’). But the stresses might also run like this: ‘And I do not deceive because I am rather simple too.’ She is simple just as other people are, only they do deceive (both themselves and others) by thinking their smart hats make them smart.

In more conciliatory moods, Smith could admit that her writing seemed ‘at first simple, almost childlike’, but then she didn’t think children were uncomplicated. In one poem a child is always being told that it’s time to go for a walk, time to play, time to go home, and finally replies: ‘It is always time to do something I am never torn/With a hesitation of my own.’ Smith’s rhythms are her way of claiming hesitations that work for her – and of passing them on to readers. One of the peculiar pleasures of her writing is the feeling it gives that it’s somehow trying to help, even as her best poems don’t appear to want to convince you of anything. In ‘So to Fatness Come’, the figure of Grief tells her to sup full of the dish of pain and she feels that he speaks ‘no more than grace allowed/And no less than truth’, which hints both at the rightness of the saying and at the sense that more might be said (the poem was included in Smith’s Batsford Book of Children’s Verse, which says a lot about what she thinks children can take – and what they might take to). Introducing the poem in performance, she noted that ‘it is what may be said when human beings lose people they love.’ ‘Human beings’ is exquisitely cool when placed so close to ‘people’, and the archness is heightened when one recalls what Smith says to ‘The Poet Hin’ in answer to his wise saws: ‘That, Hin, is something we may think about,/May, may, may.’

Smith often invites you, dares you, to think things her poems aren’t quite saying. ‘It really is tantalising …/There’s nothing I’d rather say/Than something Edifying and Unusual.’ She is aware that such ambitions make and break poetry. ‘Man is most frivolous when he pronounces,’ Mother pronounces, not unfrivolously, in one poem, and elsewhere Mother may know best when she tells her child that ‘Marred pleasure’s best,’ but what the poem knows is that such pearls of wisdom aren’t about to stop anyone yearning for other things besides knowledge. Barbara Everett wrote in the LRB (5 February 1981) of the way Smith’s ‘flawless deep needlings of God and Mother’ make the hair rise and one of the reasons for this, I think, is that the needling doesn’t quite settle the argument. Certainly, whenever guardian angels appear in her work they are no-good do-gooders with an ‘exasperating pit-pat/Of appropriate admonishment’, but then Smith has a gift for turning both exasperating questions and answers to pointed use. One poem is called ‘I could let Tom go – but what about the children?’ and back comes the reply:

Since what you want, not what you ought,

Is the difficult thing to decide,

I advise you, Amelia, to persevere

With Duty for your guide.

Smith was wary of those who took advice as well as those who tendered it, those who were, as she put it in a letter, ‘Hungry for a nostrum, a saviour, a Leader, anything but to face up to themselves & a suspension of belief’. She was also alert to the intolerance that sometimes lurks in pity, and of those who are kind to be cruel (‘sentimental writers can be very cruel’). Her sly skill with aphorism became a means of entertaining belief without hungering for it – and without handing it over as a cheerless denouement. ‘All good things come to an end,’ we learn in Novel on Yellow Paper, ‘and the same goes for all bad things.’

It’s both a good and a bad thing that Will May’s edition of Collected Poems and Drawings leaves you wanting more. In his revealing book Stevie Smith and Authorship (2010), May noted that MacGibbon’s editorial decisions in Collected Poems were inconsistent, and accused him of ‘editing by stealth’. MacGibbon’s handling of ‘Not Waving But Drowning’ is a case in point: different versions of the poem exist and Smith’s changes to the punctuation subtly alter the meaning, yet MacGibbon makes no reference to this (‘an alternative way of punctuating the four most famous words that Smith ever wrote,’ May comments, ‘does seem a variant worthy of documentation’). He’s right (the 1956 version of the poem puts the final lines in inverted commas), although this makes you wonder why he doesn’t mention another variant in his own notes: an earlier version of the famous words was ‘not waving, but drowning’, but in their final form they read ‘not waving but drowning’. Smith’s shrewd removal of the comma makes a difference, makes the words more piercing in their very refusal to pause for dramatic effect. May’s treatment of this poem is lacking in other ways: in several notes he quotes from the introductions Smith gave when reading her work in public, yet he cites nothing for this poem even though Smith’s comment on it (‘sometimes the dead cannot rest and the ghosts come back’) is a suggestive one. May also tells us ‘Not Waving but Drowning’ was written in 1954, but in a letter to Dick in April 1953 Smith wrote: ‘I felt too low for words (eh??) last weekend but worked it off for all that in a poem … called “Not Waving but Drowning”.’ Given that Smith wrote this letter a few months before she tried to commit suicide, it’s important to get the dates right.

The Collected Poems and Drawings corrects some misprints in MacGibbon’s edition, but it also introduces quite a few new ones. There are a few typos and mistakes in May’s editorial apparatus and commentaries too. I’m mindful as I write this of Smith’s ghost calling back, from Over the Frontier, that ‘the basest of all the hangers-on of artistic creation are these same commentators that are always so smart to point out what’s what and how the comma got left out and the quotation misquoted.’ But still.

May’s decisions about his source texts raise issues that are less clear-cut. A brief Note on the Text begins by explaining that Smith was ‘clearest’ on editorial matters after seeing her poems in print, ‘once decisions became errors’. In Stevie Smith and Authorship May wrote engagingly about Smith’s mercurial attitude to her printed texts (sometimes amending poems in her own and friends’ editions, shifting drawings from one poem to another, changing lines when reading the poems aloud and so on), so the use of the word ‘error’ here perhaps plays down her sense of fluidity, and of a text in flux. May notes that she never sent post-publication versions of her poems to her editors (they were used by her for performances and broadcasts), yet ‘as far as possible, these amended final versions have provided the source texts here.’ Editors have to plump for one version of a text, but it’s not entirely clear what ‘as far as possible’ means in this context, or what might count as the ‘substantive variants’ that are meant to be recorded in the notes.

Sometimes May provides details about Smith’s changes to her performance scripts, sometimes he doesn’t: in his note for ‘Mother, among the Dustbins’, he comments on the introduction Smith used when performing it, but makes no mention of the significant revisions she made to the text. The printed version of ‘Do Take Muriel Out’, he says, ‘follows performance’, and although he notes two changes Smith made, he misses a third. Smith muddied the waters here because she did different things in different performances, but if you’re in the business of making or recording changes then more clarity is desirable. In his note for ‘My Cats’, May refers to Smith’s aside about the North Berwick witch trials, but doesn’t give a variant: in the printed version, the witch likes to ‘ruffle up his pride/And watch him skip and turn aside’; in performance, she watched the cat ‘spit’, not ‘skip’. You want to be reminded of Smith’s spit as well as her skip.

May’s edition still has plenty to recommend it: it contains previously unpublished poems, useful appendices, engaging notes (MacGibbon’s Collected Poems had none), and is attentive to Smith’s range of allusion – Homer, Pindar, Seneca, Catullus, Wither, Young, Blake, Scott, Wordsworth, Byron, Tennyson, Browning, Eliot and many more. May’s interest in Smith’s performances makes you want to return to her recordings, gets you to think about the kind of life her voice could bring to the poems, and prompts you to consider how the poems might resist that voice. In some ways, Smith’s success as a performer is fitting, for the poems themselves often have the quality of a performance. Their utterances have a peculiarly staged quality, as though the speakers aren’t simply inhabiting the words, but parading them. It’s not that the effect is ironic; it’s rather that the poem comes at you as some sort of rueful spell, or as a form of observance to a feeling that isn’t quite sure of itself. ‘The awful thing about “love”,’ Smith wrote to Terence Kilmartin, ‘is that it is easily so completely forgotten, & best so. Because when called up again it is always something false, made up really. Or sounds so.’ That qualifying coda is a key to her strength; she’s at her best when she’s exploring just how much desire goes into memory – and vice versa:

‘Pad, pad’

I always remember your beautiful flowers

And the beautiful kimono you wore

When you sat on the couch

With that tigerish crouch

And told me you loved me no more.What I cannot remember is how I felt when you were unkind

All I know is, if you were unkind now I should not mind.

Ah me, the capacity to feel angry, exaggerated and sad

The years have taken from me. Softly I go now, pad pad.

Calvin Bedient, in a superb essay on Smith, notes that ‘she sometimes uses metre as a foil, to show where we have been or would like to be before showing where we are.’ Here it’s as though the ghost of the limerick form in the first stanza wants to reframe the event, to make it less shocking (more pleasurable, even) by putting it to a tune. The second stanza is a world away from all that now – or would like to be. Anger may have faded, but the capacity to feel ‘exaggerated and sad’ is indulged even as it is disavowed, and was in fact sounded from the first note: ‘I always remember …’ Finally, there’s the sign-off: ‘Softly I go now, pad pad’ might be a means of restaging their parting of ways, making the dignified exit now that couldn’t be managed then, or perhaps ‘go’ is more of a confession about the way he now prowls round his past. ‘Pad pad’ contains both softness and stealth, and takes with it not just a memory of the tigerish, but the possibility of its continuation. The poem cradles a barely whispered hope for a making-up (‘I’ve changed!’) along with a sense that such a change would leave them with nothing left to desire in each other.

The delicacy of tone in Smith’s best work also means that the poems can sometimes be less effective in performance. The recordings are riveting, and you can see why, as Anthony Thwaite observed, ‘her readings became her poems.’ Yet Smith didn’t feel this state of affairs was wholly becoming to her art. She noted that ‘always with the spoken word something is lost … if the poems cannot be seen, read, and reread, on the printed page’, and her 1965 reading of ‘Pad, pad’ brings out the archness of the poem at some cost to its sadness. In her performance of ‘The Blue from Heaven’, when Arthur says he wishes ‘to ride in the blue sunshine/And Guinevere I do not wish for you’, the statement prompts laughter in the recording I’ve listened to, which makes the lines ‘So she went back to the palace/And her grief did not seem to her a small thing’ seem almost a rebuke to the audience when they arrive a couple of stanzas later. Smith enjoyed wrong-footing her listeners, but the toing and froing of their moods in the auditorium means that they experience the poem differently from readers who are confronted by its enigmatic bluenesses on the page. I haven’t yet met anybody who didn’t smile when they encountered the line from ‘The Jungle Husband’ as he writes drunkenly home to his wife: ‘Yesterday I hittapotamus’ – and the line only improves when Smith reads it aloud. But it’s much harder in performance to catch the disorienting resonance at the end of ‘I Remember’ when the old speaker’s young bride asks him, on their wartime wedding night, about the planes above them:

Harry, do they ever collide?

I do not think it has ever happened,

Oh my bride, my bride.

Paul Muldoon reads this as poignant, hears the last line as exasperated and senses an ‘almost inevitable lack of consummation’ between the couple. Smith, however, talks of it as ‘a happy love poem … a boss shot at a general feeling of warmth and affection’, and reads that last line in performance with a knowing smile. One can imagine other tones too: arousal, assurance, wonder, a kind of spent yearning, and perhaps even an envy of guilelessness.

To rhyme ‘collide’ with ‘bride’ is to underscore the separateness that makes itself felt even in – especially in – the closest relationships, and this seems to me to be Smith’s most persistent subject:

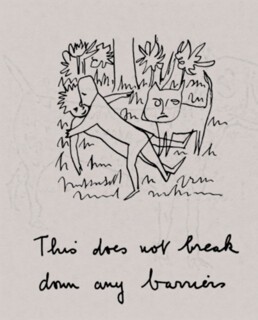

The drawing accompanies an early poem, entitled ‘Conviction (IV)’, in which she announces ‘I like to get off with people,/I like to lie in their arms.’ Given that various kinds of conviction and lying are in play, ‘to get off’ perhaps carries a legal as well as a sexual charge – as though the poem were happy to imagine shared pleasure as both guilty and guiltless. I say ‘shared’, but Smith’s ‘with’ is double-edged: she might like both of them to get off at the same time, or she could be saying that she likes to get off with the aid of others. As May points out, Smith added the caption when she used the image again in her sketchbook Some Are More Human than Others. It’s not immediately clear whether the text is a lament or a consolation (perhaps the latter once you notice that smile). And it’s not clear what ‘this’ is: it could refer to the act the picture depicts or to the picture itself; or perhaps the uncertainty allows for the possibility that sex and art are sublimations of each other. The cat isn’t about to give the game away, and the whole thing feels touch and go.

‘Many of my poems are about the pains of isolation,’ she wrote, ‘but once the poem is written, the happiness of being alone comes flooding back.’ Writing is a private therapy of sorts, but it’s a conviction about other people too (the phrase ‘the happiness of being alone’ is something like Wordsworth’s ‘bliss of solitude’; it’s offered as a psychological fact, not a personal predilection). In a letter to James Loughlin, Marianne Moore wrote that ‘we all of us need Smith’s poems and drawings – to counteract the estranging determination of some writers of prose and verse to obtrude on us their wanton unnaturalness.’ Smith was delighted by this comment – not least, one suspects, for its willingness to make a claim about ‘all of us’ without its seeming like an obtrusion. The adjectives so frequently used both to praise and to criticise Smith’s work – odd, quirky, eccentric etc – are sometimes estranging not because they are wrong, but because they can imply that these qualities place her far away from us, rather than both far and near. Smith set a better example when writing about Maurice Baring’s Lost Lectures: ‘This is the sort of book I like. Himself is not his only interest, and yet it very well might be.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.