This has been a rich time to explore 19th-century Scandinavian painting. Six years ago London and Edinburgh shared a revelatory show of Christen Købke (1810-48); while in 2014-15 the National Gallery showcased the less well-known but more extraordinary Peder Balke (1804-87): one of those rare artists whose pictures became smaller as he got older, and whose scraped, scratched grey-and-black oil-on-board images of the Northern Lights are among the most surprising pictures I’ve seen in the last few years. Now it is Paris’s turn, with Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg (1783-1853) at the Fondation Custodia (until 14 August). These shows have been the more important because such painters are meagrely represented in British public collections. According to Art UK, we own a single picture by Eckersberg, four by Købke and one by Balke. All, except for two Købkes in the Scottish National Gallery, are in London’s National Gallery.

The three artists were of modest origin: Købke was the son of a baker, Balke came from ‘the lowest rank of peasant society’, while Eckersberg’s father was a carpenter. Each made his way early by talent, and by the luck of that talent being recognised by those around them: Balke’s studies were funded by local farmers – several of whose farms he decorated in recompense. All three were trained at state academies (Balke in Stockholm, the other two in Copenhagen), and attracted official, even royal support. This was partly genuine connoisseurial interest, but also a patriotic impulse. Painting, then, there, was part of nation-making, of the visual defining of those northern countries.

Eckersberg, the principal painter of the so-called Golden Age of Danish Art, was the most cosmopolitan of the three. In September 1809 he won the local equivalent of the Prix de Rome. But official money was tight, and he was advised to wait for the previous winner to return before taking up the prize. So Rome (1813-16) was preceded by Paris (1810-13), where he spent a year ‘beneath the eye’ of Jacques-Louis David. Here he received the full stamp of French neoclassicism. But David, whom Eckersberg described as a ‘very rigorous and precise teacher’, was also ‘against submission to one particular overall style’, and Eckersberg’s output is various in manner as well as matter.

If asked, he would describe himself as a history painter (mythological, biblical and classical), because that was then the noblest category of art. But he also painted portraits (he was celebrated for bringing ‘the French style’ to Copenhagen), scenes of urban life, nudes, naval pictures and cloudscapes. Early on, he composed the Hogarthian Tale of a Fallen Woman and recorded contemporary events (his 1807 Bombardment of Copenhagen shows the city ablaze at night after the attentions of the British navy); while for 35 years he supplied religious pictures for churches. There is one in Bjarnahöfn, meaning that Iceland is the equal of England in Eckersberg ownership, as well as its superior in football.

This may make Eckersberg sound as if he was anxiously peripatetic in manner; the Paris show reveals him to be always securely himself, yet frequently on the move. He was also progressive: on his return to Denmark, he became one of the first professors in Europe to advocate and teach plein-air painting. And whereas in his own student days, he had learned to draw nudes only from plaster casts, he now introduced both male and female models; further, he had his students not just draw but paint from live models. He would paint alongside his pupils, and his five large academic nudes of 1827 are wonderfully instructive about the ways light and shade fall on flesh.

When he showed his first works to David, the Master reportedly commented: ‘Monsieur, I don’t know how anyone can paint like that in your country.’ It might sound like a put-down, but is probably indicative of genuine Parisian surprise. Under David’s eye, Eckersberg developed into a sophisticated European artist: see his grand portrait of the assembled Nathanson family, half-frieze, half-dance, with the eight children celebrating the return of their parents from being received by the Danish queen. This social triumph should not be underestimated: when Mendel Nathanson arrived in Copenhagen at the age of 12, he was illiterate and spoke only Yiddish. He had come from Schleswig – as had Eckersberg – and was a key patron for many years. (We might remember the later Thadée Natanson of Paris, patron of Vuillard and others at the far end of the century.) The neoclassical style, in its determination to avoid melodrama, can seem cerebral and cool, but in Eckersberg’s hands it was not an idealising mode. It is always tempered with realism. So the daughter whom Sophie Hedwig Løvenskiold holds proudly up for our inspection is plain, pink and quite possibly teething; while Frederikke Christiane Schmidt, the wife of the East India merchant Albrecht Ludwig, crocheting away beneath her ostrich-feathered hat, is fearsomely double-chinned. But his eye can also be both tender and humorous, as in the brilliant The Model Maddalena: the sitter’s sad-eyed mien lies beneath a hat which is a joyful explosion of blue, pink and white flowers. In Bella and Hanna, the two eldest Nathanson daughters are posed with striking neoclassical geometry, one full-face and two full profiles, left and right; it’s just that the second profile is that of their pet parrot.

Eckersberg’s work is always highly considered and well executed; but posterity is ruthlessly self-interested, and inevitably parts of his work plead in vain. Some subjects engage us less fully, less directly. Also, we now give as much attention to the preliminary drawing and the sketch as to the finished work: indeed, ‘finish’ is almost a suspect word. So we attend to David’s quick croquis of Marie-Antoinette on her way to the scaffold as much as to, say, The Tennis Court Oath. A portrait drawing by Ingres can engage us more than some of his grandest historical works. More widely, there is a slippage in the hierarchy of genre. And so with Eckersberg: currently, his best-known painting is not one of his historical pictures, but rather a contemporary view of a place where some of that history unfolded. It is an urbanscape of the Roman skyline seen through three arches of the Colosseum; modestly sized (indeed, many of his Roman pictures are smaller than you might expect), yet solidly, carefully structured. However, it is that very structure which makes for its novelty. Whereas some old Roman remnant, like an aqueduct, might traditionally function in a picture as a mid-distance eye-catcher, here the masonry is deliberately in our faces, blocking as much as enhancing the view. Indeed, it is the view: we are being told to examine these blocks of stone, seen not in full sun but rather in warm shadow; to inspect this ancient form of construction, these sturdy pillars with modest decoration, these trusty keystones, and to reflect on time’s fretful depredations, its chippings and stainings and discolorations.

Eckersberg was clearly thrilled by Roman stone and brick lit by a southern sun; the way he revels in their friendly crumblingness reminds us of Thomas Jones’s earlier work in Naples. Similarly, his cloudscapes from the mid-1820s – many of them now lost – alert us to the fact that it wasn’t just Constable who was looking skywards at that time. Eckersberg knew neither of these artists or their work (though he did meet Caspar David Friedrich). Constable, of course, is another example of our re-evaluating tendency. Nowadays we often find ourselves preferring the full-sized preparatory oil sketches to the finished paintings; and I know one art critic who thinks Constable’s oil-on-paper Rainstorm over the Sea (c.1824-28) his finest single work.

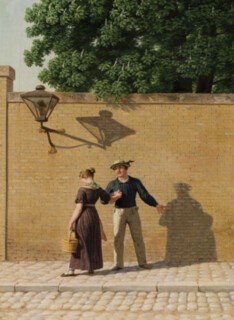

The other part of Eckersberg’s output that speaks to us much more clearly nowadays are what might at the time have been treated as mere Danish ‘genre scenes’. He painted some in the years before leaving for Paris and Rome, and returned to the mode again after a 15-year gap. In Langebro, Copenhagen, in the Moonlight with Running Figures (1836), something is happening off-picture to our right, provoking alarmed citizens to run straight towards us across the bridge and others to stand rigid and point. Is it a drowning? Or (more likely, given what appear to be red reflections on distant windows) a fire? We witness the effect, but not the event itself. In Street Scene, Wind and Rain (1846), three pedestrians, an umbrella and a shouldered sack good-humouredly collide against a backdrop of brick and a footdrop of cobbles. While in A Sailor Taking Leave of His Girlfriend (1840), two figures hold parting hands while the distance between their bodies suggests the distance shortly to come about; but the high sun which casts their shadows onto the orangey wall behind transforms the couple into a single melded shadow (suggesting what they have already been, or what is being promised on return? And does the sailor’s hand explicitly point to this promise?). In these last two pictures, there is an improbable foretaste of Vallotton’s strange figure-interlockings. In all three, there is a sense of the cosmopolitan who has returned home; of neoclassical clarity of idea yielding to ambiguity of effect; and of Eckersberg seeming at his most Danish.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.