The year we killed our teacher we were ten, going on eleven. Mitch went first, the terrier, a snappy article with a topknot tied with a tartan ribbon. The morning we saw him we hooted. He didn’t like us laughing and he flew to the end of his lead, and reared up snarling and drooling. ‘Hark at the rat,’ we said.

Rose Cullan said: ‘Hark at Lucifer.’ He twisted, he screamed, his claws lashed out. The devil has several names and Lucifer is one.

It was because of an emergency that she brought him to school. She was fetched out of arithmetic by a message, and she had to go home and get him. Rose’s father said it was a gas leak. All that row of houses had to pack a bag and evacuate.

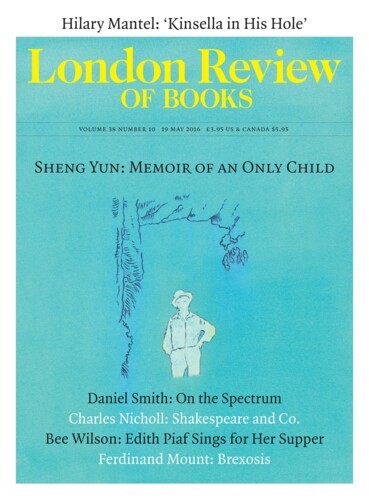

She couldn’t bring him into the classroom so she had to ask Sammy Kinsella to mind him. It being playtime when she got back, we were there to witness, and we could see her, half in and half out of Sammy’s hole. To reach Sammy you went down steps, and pushed open a battered green door that snagged and bumped along the ground. Behind it he stoked the boiler that kept us heated. The boiler was at the back behind twenty feet piled high with trash, smashed picture frames and three-legged chairs, scarred desks stacked with their feet in the air, globes of the world with obsolete countries, dusty crates and collapsing boxes that no one had looked in since Adam were a lad. He had a bedroll in there somewhere, snug at the back, and if so inclined he never went home but lay down among the rubbish.

I say rubbish, but you never knew what Kinsella liked. Ask how long he’d been in the hole and the answer would come: ‘Why the devil do you want to know, mister?’ He wanted you to think he’d always been there and, after a manner, you could believe it. First they built the boiler, then they built Kinsella to stoke it, and then the school around them, walling them in with black stone that must have stood a hundred year.

She – our teacher – stood at the door peering in, not knowing if she could cross the threshold. ‘Oh, Mr Kinsella, could you kindly look after Mitch for me till after dinner? There’s an emergency at my home and we have to vacate the premises.’

We’d never heard her talk like that. The sweetness was wasted. Kinsella stared at her, then at the beast. ‘What do you call that?’ he said.

‘I call him Mitch. My little Mitch.’

‘Right,’ Kinsella said. ‘What’s it for?’

She faltered. ‘He’s my companion,’ she said.

Kinsella sniggered. ‘Fit for thee.’

There was no sacking Kinsella. He was related to a priest.

‘I’ll come for him at dinner-time,’ she said, wheedling.

‘And what will you do with him after?’

‘The emergency will be over by then. Please, Mr Kinsella, you’re my only hope.’

‘Am I?’ Sammy said. ‘Oh well.’ He pointed to the railing. ‘Fasten it there.’

‘Can’t he come into the warm? It’s coming on to rain.’

‘I have rat traps down here,’ Kinsella said. ‘For obvious reasons. You wouldn’t want his leg snapped, I take it.’

She looped the lead around the railing. Kinsella folded his arms and watched her. ‘Now, Mitch,’ she said, ‘I’ll have to put your little coat on.’

She squatted down and unzipped the big shopping bag she carried with her every day. It had check on the side that matched the dog’s topknot. It looked heavy; she was rumoured to have a fat leather purse. She rummaged in, and took out a contraption which she dangled in the air, a little blanket with straps to go under his belly. Rose Cullan said: ‘Miss, that’s not a coat.’

‘It is a coat for a dog,’ she snapped.

We stood and watched as she tried to feed the dog into it. The dog wasn’t having it. He writhed and foamed and snapped at her. ‘Mitch, now, sweetie pie! Come on now, my little baby boy!’ She was sweating and breathing hard as she tried to keep her fingers out of his teeth.

‘Comic,’ Kinsella said.

Once she had got the beast trussed up: ‘Thank you, Mr Kinsella.’ She picked up her bag and gave us a hard stare. Then she set off down the hill to have her dinner with the other teachers.

We had our dinner in a Nissen hut in those days. They called it ‘the dining hall’, as if we were dukes. At the end was a partition, and behind it the teachers ate. Not the nuns – they went home to their own dinner in the convent – but Mrs Parker and Mrs Bacup, and Miss Dowd who taught the babies’ class. In privacy, they set into big pies, like Desperate Dan: at least, we thought so. But our teacher brought sandwiches in greaseproof paper. When she first arrived she had given scandal by fetching out meat paste on a Friday. Miss Dowd had been heard to say: ‘I know she is Not of Our Faith, but is the woman a bloody heathen?’

The damage from this had never been mended. In the classroom she was more savage than the standard, and that made Mrs Parker and Mrs Bacup rivals to her, and even Dowd found the energy to start hitting the babies with double rulers. The odd parent came in, steaming. The question was raised: ‘Why employ a Protestant in the first place?’ ‘Oh, that’s diocesan reasons,’ Father MacAfee said. ‘You wouldn’t understand the way they think in Shrewsbury.’ It was an inconvenience for the nuns, who had to supplement her teaching. She had to be withheld for the first lesson every morning, when from 9 to 9.45 a.m. we learned about the love of God. Then the bell went. In the waiting time, her force had condensed. She charged at us, like Sonny Liston out of his corner, laying about her with her fists.

Till playtime we learned long division and simple fractions. She knuckled them into our heads. Then the bell went and the Catholic teachers went to the babies’ classroom, where there was a sink and they could get water, and brewed up, and had shortbread. Our teacher brought her tea in a flask and drank it hunched over her desk. If for any reason you had business in the school at playtime, you could see her through the misty panel at the top of the glazed door: sucking, her eyes blank, getting her strength up for the next round.

It would have been late January when the key of the biscuit cupboard went missing. First they held some of the babies upside down, to see if they’d stuffed it down their jumpers; so Rose said, she being one of those big girls whistled up to help with the babies when they got fractious. They didn’t find it, so then the Top Class was to blame. The known troublemakers were collected and punched about by Father MacAfee, who was always invited down from the church when there was a mystery. When no confession resulted he creaked among us with a face of thunder: ‘I am prepared to lay the leather across every member of this class, the girls not exempted.’

The teachers said: ‘Our biscuits are trapped in there. We got that shortbread for Christmas. It isn’t fair. Honestly, the spite and malice of some folk, it has to be seen to be believed.’

Once they gave up on the key, Mrs Bacup brought in pink wafer biscuits. That day there were crumbs all over the teachers and all over the floor. Dowd brought Fig Rolls, and the convent sent Morning Coffees that were damp. Every day before the bell went Rose would wash the beakers in the babies’ sink. She’d boil a kettle to do it, and while she was waiting she would while away her time by tying up the babies’ shoelaces and sharpening their pencils. ‘You’d think once in the year,’ she’d say, ‘they’d leave me out a biscuit.’

Peter Hinchcliffe said: ‘Who do you think you are, the Queen of Sheba?’

Our school was situated on a lane, unmade in those days, that ran uphill to high ground. On the Top, we called it, and from it the land fell away to Slaide Hill, a dense tangle of treetops, stony and steep. It was there we brought the dog, struggling inside its bag.

Kinsella had gone back inside his hole and did not see us take it, and if he did he never minded. He had his own pursuits to attend. Our dads used to say: ‘Go near Kinsella and I’ll brain you.’ But they brained us anyway so we took no notice. We knew to keep the babies away from him, in case he went jabbing into them with his black finger. But after you were about seven Kinsella wasn’t interested in you, only in whatever you might give him for his tin. He had a collecting box on the side, near his bedroll, and if you went that far in his hole you had better donate or he might not let you out. Mother Columba said the collection was for Black Babies. ‘You should give generously of your lolly money to Mr Kinsella,’ she said, ‘for that man is one of God’s holy fools, and his efforts for Africa are unstinting.’ ‘We have a whole continent to save,’ she said, ‘and simple souls like Sammy will help us do it.’ When enough was built up in the tin, Sammy used it for his beer fund. Mother knew but she feared Kinsella for what he might say about her when he was drinking at the Rat Trappers Arms. It was called the Pear Tree, but it was known as the Rat Trappers for obvious reasons. Columba’s name was mud there.

The dog party was seven in number. The three girls, Rose, Bridget, Stella, then myself, Peter Hinchcliffe, Barry with the red hair and Peter’s brother Vin, who tagged after. The dog had screamed when we bagged it, and as we jounced it along it writhed and buckled, but of the ones who saw us go out of the school gates, nobody raised the alarm; they only raised a hand, as if to say, ‘Blessed be thou.’

‘Dirty work,’ Bridget said, ‘but I don’t mind it.’ I wanted to kill the brute with my hands, but Rose said: ‘You moron, do you want it to rip your finger off?’ While we had been boasting what we were going to do, the girls had been thinking it out. When we loosed him from the bag, Rose dived on the end of the lead and whipped it around his neck. His snarl cut off to a wheeze. Peter said after: ‘Did you see the speed of it? As if she’d been doing it all her life.’

It was February, before half term, a day of hard frost and startling light. Since September, our teacher had twisted our ears, bruised our knuckles and waged a terror on us by always threatening worse, and then by doing worse, week by week, so that you thought: ‘Where will it stop?’ We had no faith in anyone to save us and we knew it was useless to ask. Peter peeled his brother’s hat down over his eyes, so he wouldn’t look at the death throes, but Vin peeled it back: ‘I want to see the bugger kick.’ Peter rapped his skull for swearing. ‘Stop fighting,’ Stella said, ‘hurry up.’ Soon the bell would be ringing for afternoon school. Rose looped the beast’s lead over a bough. Its front paws played the air. Vin giggled: ‘Give us a tune, Mitch.’

We trooped back up to the playground, in time for the entertainment. When our teacher came back she had her bag in her hand – lighter by her sandwiches, unless she hadn’t any that day because of the gas leak. ‘Sammy?’ she called. ‘Mr Kinsella? Are you there?’

Sammy Kinsella came out wiping his chin. He said: ‘I’m having my dinner.’

‘What, still?’

‘It’s cheese and onion pie,’ he said.

Sammy used to heat his dinner on a tin plate on top of the boiler. The rumour was that his food wasn’t always what he admitted. I don’t mean he was a poacher.

‘Where’s my dog?’ she said.

‘I don’t know,’ Sammy said. ‘Perhaps somebody’s eaten it.’

We watched her flush a mottled pink. It was just like when she hit us but it wasn’t with pleasure. ‘He was tied to that railing.’ She whipped around. ‘Have you children seen a dog?’

‘Yes, many a time,’ young Vin says. ‘Little ’uns, big ’uns, white ’uns, black ’uns.’

She dropped her bag and flew at him. She wore a ring and it struck his tooth. I can hear the chime now: I could sing you the note, or a woman could. The little lad put his hand up, and blood ran between his fingers.

‘Mitch, Mitch!’ She whirled about. ‘Where’s my dog?’ She turned her fire on Kinsella. ‘He was in your custody.’

Stella said: ‘Oh, miss, don’t blame Sammy Kinsella. I shouldn’t wonder if he’s been taken by gypsies. They’re camping on Slaide Hill. They skin them, Miss, if they can get a little dog, and make purses out of the skin, and sell them door to door.’

Our teacher bent over and retched. No sooner had she done it than Vin spat blood on his shoes. ‘Blimey,’ Rose said, ‘it’s like Armageddon.’ Vin always said, when we talked about it after: ‘It were worth it, only the blood give me a shock. She didn’t knock the tooth out but she easily could. And Christ on a bike, I were seven! Seven! And I tell you, when she punched me she put her weight behind it.’

Stella had stood over Vin, patting him, and given him a clean hanky. Her initial was embroidered within a ring of daisies. She was that kind of a little girl, dainty, her hair pinned in a plastic slide, her handwriting neat and the ink always blotted. I often wonder where she is now. She went down south by the end of the year. She said she’d write but she never. Stella Maris, her name was. Star of the sea.

Father MacAfee came down the next day, huffing. We had, he said, a special responsibility to Miss, because she was Not of Our Faith. ‘Do you want her to think,’ he demanded, ‘do you want the world to think, that Catholics are the kind of people who steal dogs?’

We stared back at him. We didn’t mind if they thought that or not. Leniency might be procured, he roared, in exchange for information. Otherwise should the culprit be found to be any member of this school, whether boy or girl, the consequences would be severe. The culprit, we were to understand, could look forward to being maimed by Father MacAfee, then prosecuted in the courts. Did we realise at all, he asked, that it was a criminal matter? Did we know a dog was property? Miss had informed the police. Those police had informed other police. It would be taken to the highest level. He had hoped he would never live to see the day, when shame was brought on our church and all the Faithful in it.

Columba came in, and added her voice to his. He walked between the rows, his brogues squeaking. Absolute silence he would obtain, he said, and would cut the tongue out of any child who spoke unless it was to volunteer himself for punishment – or herself, of course. He would keep us here for as long as it took, he said, though night came down.

It being February, night did. It was MacAfee who broke first. He was less inured to hunger than we were. At half-past five, Stella put her hand up.

‘Girl?’

‘Father MacAfee, my mother was in the street this dinner time. She saw where Mrs Dwyer was getting a bit of undercut for your tea. “I intend to cook this for Father,” she said, “with a nice fried onion.”’

The words undid him. He was drooling before, at the thought of what he’d do to us, but now he weakened; he could smell the onion in the pan. If it had been anybody else said it, he wouldn’t have waited for his steak, but chewed the bold girl’s head off and sucked the bones. But once before he had cuffed Stella Maris, and her father had come up the lane to talk it over, waiting for him at the back of the church in the gloom. ‘I’ll pyx and chalice you,’ he said. ‘I’ll kick your arse from here to Glory Be. Lay one finger on the star of the sea and I’ll pull your Pope Pius off and pickle it in your piss.’

‘We will take this matter up tomorrow,’ Father MacAfee said.

Bridget says she sometimes sees the dog in her dreams, as it dangles from the bough like a sick pear. In waking life she never saw it. At four o’clock we hurried home, keeping to the path, not speaking to each other. Barry said: ‘The criminal returns to the scene. But we are going home to our teas.’

It was about eleven next morning the news spread through the school that the corpse was found. Overnight, the cold had gone to work. The fur was stiffened into points. The tartan bow, the topknot, were rigid with ice. Mitch hung frosted, like a bauble on a Christmas tree.

I remember Peter Hinchcliffe saying: ‘The way Miss carried on, you’d think Herod had massacred the Innocents.’ She ran out of the classroom, leaving Columba gaping. The whole class stood as one. We dropped our books, we scattered our nib-pens, we left them where they lay and ran out into the icy lane. Our teacher went sailing down Slaide Hill, her feet skidding sideways: ‘Mitch! Mitch!’

She dropped her bag, that she was never parted from, on the rutted path. We heard her crashing below amid the trees. Bridget opened the bag and looked inside. She found the fat leather purse but she didn’t touch it. We were not robbers. Instead she cast around for a dog turd, to slide it in. It wasn’t Mitch’s, but as Stella remarked, ‘she’ll think it is.’ We left the bag in the lane, for her to find when she came climbing up the hill, wailing; its wide jaw was unzipped, so it looked as if it were laughing.

We never saw the police inspector that we were threatened with. We saw plenty of Father MacAfee, belt in hand. He was sure the Top Class was to blame, just as he was sure we had been to blame for stealing the key of the shortbread cupboard. Barry said, quite reasonably, that if we had stolen the key we’d have stolen the shortbread too. And it was just as Barry spoke – I don’t know whose idea it was, we all had the idea together – we realised that it was useless to kill the dog, unless she followed after.

Because after her two days’ sick leave her manner to us was markedly worse. The only difference was now she would burst into tears while she was beating us. Father MacAfee was threatening to thrash the whole class to within an inch of its life or beyond, if no informer came forward. He said he would get in a fellow priest to help him with the heavy work. Bridget said that very likely the bishop would come up from Shrewsbury. Mrs Dwyer could lay on a special tea for him.

‘Tea,’ Barry said. One playtime, unscrew her flask; add something, not sugar. But the flask was kept in her bag, on which she now kept guard. When she opened it to extract our exercise books, where she would have run amok with a red pen, she opened it only the slot she needed; a smell of disinfectant belched out from inside. Besides, we did not know what would poison her. Mitch had been a take-it-or-leave-it business. If the dog had got away, it couldn’t have named us. But if we failed, just gave her a bellyache, they might hang us. We knew they didn’t hang children, though some used to call for it. But why would they not keep us locked up till an age where it’s allowed?

Surprise was what we looked for, and to wait till after dark. Someone to hold her back for ten minutes with a silly question, or by some spectacular misdeed, while the crowd of children swarmed off down the lane: then we might wait, crouching, breathing subdued, ears pricked, till we heard her making her way downhill. With surprise working for you, you could trip somebody, you could tumble them down the hillside among the tree roots. Once you had begun the business they would be lost to sound and sight. Lay them at ground level and Slaide Hill would grow over them. They would grow as vegetation in a year or two. And if a corpse was found why then, as Stella said, blame the gypsies.

Yet Peter was against tackling her by main force. She was strong as a man, and though he was big for his age and Bridget no mean warrior, neither Barry nor I had the heft to fell her. Vin was a tiddler. With the girls, even Bridget, there was always the risk that pity would weaken them. We could have brought in allies, willing fists enough. But the effort of the dog had sealed us together. ‘A covenant,’ Barry said.

You could see even then that Barry was the one among us who would go far. It was no surprise when later he was accepted to train for the priesthood. Once he was at the seminary we’d say to him: ‘Ask them, ask them, ask the Fathers about the bargain we made. Say we don’t understand the terms, ask them were we old enough to do it, ask them if it’s still valid after all these years. Say you’re asking for a friend – they don’t have to know you’re part of the scheme.’

But he thought it was best left. As for the deed itself, Bridget once asked him – just before he was ordained, and back home for a holiday – if he’d told it in confession.

‘A year back,’ he said.

‘And what did the priest say?’

‘Not much.’

Bridget said: ‘Not much? Well, I dare say he’d heard worse.’

Barry said, he had to pretend he had. He wouldn’t want to come over as some sort of green novice – ‘Oh my God, what’s this you’re telling me!’ – and falling off his stool with fright. Nor would he want to come over as a snitch. ‘These blokes I mix with now,’ Barry says, ‘they’re hardened confessors from the old country. Half of them themselves are in the Rah, and they’ve blown up a post office or similar deed. If you say to them, “I’ve killed a fella,” they say, “Five Hail Marys and spare me the details.”’

When we decided to enlist Kinsella we went to see him in his hole. I remember a stench that day, beyond the customary rot. Rose says: ‘Mr Kinsella, that’s never cheese and onion pie? If it is you want to look to your recipe.’

Kinsella wiped his mouth. ‘Why do you need me? You did all right with the dog.’

‘Yes, but a whole woman,’ Barry said.

‘Ah do help us, there’s a dear soul,’ Rose said.

Kinsella snorted. A smear was left on the back of his hand from his food. I avoided looking at it. It was Peter Hinchcliffe that came straight to the point. ‘We’re here to sell our souls,’ he said. Kinsella looked us over and said: ‘What else have you got?’

We were leaving, cast down, when he called us back. ‘Go on then.’ Out of his back pocket he produced a screw of paper, and from behind his ear a pencil. He made us write our names down. There was some dispute over Vin, who had not yet made his first Holy Communion. Sammy maintained he was not worth the same as the rest of us. But he was only a few months off, we said, and after all he was baptised, and that was half the battle. Finally Sammy was persuaded. We climbed out into the air.

He had made us write the date on the paper, and that’s why I remember it still. We don’t celebrate every year, and we avoid the date itself. It’s unlikely the coppers would be on it, after all this time – but you could get some young blood who doesn’t know how things were managed, or that the Pennines were self-policing in them days. When we do arrange a get-together we don’t go to the Rat Trappers but to a place in Saddleworth where nobody knows us. We are down one these days; even at seven, Vin had fags in his pocket and his brother used to punch him for lighting up. ‘I miss our Vinny,’ Rose says, ‘he was taken too soon.’ Bridget says: ‘I wonder where he is today.’

It was understood getting her off the path would be Kinsella’s responsibility. He’d use a shovel, initially, and then when he had her down, we would do the rest. What he said when he stopped her, I don’t know and I’ve never asked. We worked in silence, once Kinsella got her off the track and the sack went on. But for the absence of the dog lead, it was not unlike the first time: the blind yapping head, and Rose whipping the rope like charming a snake. But it wasn’t easy: the bulk and weight of the woman, and Sammy after his first effort showing no disposition to put his back into it. It wasn’t a case of hang her up and leave her. We couldn’t take that chance. True, she was weakened by what Kinsella did. But he stood back, wiping himself down, and left the rest to us.

I would say it took not above ten minutes. But we stood over her for longer, to make sure there were no errors. If the dog had come back to life, what could he do but yap? If she came back to life, she knew our names. Before we got the bag on we saw the light in her eyes. She thought we were weak and wouldn’t do it, so she started up to squawk: ‘I’ll addle you, laddie, I’ll pith you, you’ll wish you were the dirt beneath my feet.’ Soon she was the dirt beneath ours, and moreover we had big shoes. They used to say if you lift the eyelid of the victim you’ll see a picture of the killer there, printed on her retina. It’s bollocks. Peter checked and there was nothing to see. ‘It gives me great pleasure,’ Rose said, ‘to think she died in sin and went straight to hell.’ She might have repented, as her ribs went in. But she was not of our faith anyway, so not of a shape to be forgiven, nor of a mind to change. Barry said as we came away: ‘They’ll have to give us a holiday tomorrow, unless Columba comes down to teach us. Columba doesn’t frighten me because I know her bloody tricks.’

Barry shut his mouth then and didn’t speak. He didn’t speak for a week. No one hit him for it. It was thought natural to be shocked into silence when a teacher had been found divided, with her head on a gatepost in the top lane, her bag vanished, and remnants of her snared in the underbrush and smeared in the tree roots down Slaide Hill.

It wasn’t until I got through my own door that my heart ceased drumming. My mam said: ‘You’re late, love. I’ve cooked a sausage.’

I realised only then that my mouth was dry. ‘I should wash my hands.’

‘You’re getting picky, aren’t you? Eat up. Sammy Kinsella would kill for a sausage.’

A jolt went through me, and my heart set off again, thudding in my ears. ‘Sammy Kinsella, what’s he got to do with it?’

She stared at me. ‘Nothing. His name just come into my head. What’s up, love, are you poorly?’

I looked at the sausage, and thought of her tongue coming out, how we’d tried to jam it back in her mouth, and how Rose said: ‘Oh bugger it, let it hang out, no bugger’s going to see.’ I picked up my knife and fork, but knew I’d not get the better of that sausage if I sat over it till midnight. When mam went out into the dark to the dustbin, I scooped it to the back of the fire.

She came back in wiping her hands. ‘All done? You must be perking up. Do you want rice pudding?’

I made sure I didn’t look at the grate. It’s still there in my imagination, that sausage, one end blackening in the coals.

There was the usual palaver, after she was pieced together. Investigation, inquest. There wasn’t a mass for her, as she was Not of Our Faith. Because of the inquiries it was some time before she could be buried, and then it wasn’t here. And if it wasn’t here, who cares where it was? As for employing non-Catholics, the experiment was over. The diocese had to buck its ideas up. And MacAfee was moved on. There was a feeling he’d taken his eye off the ball.

The check bag was recovered after some weeks, tumbled down a bank. The fat leather purse was in it, and Mother removed the change and gave it to Black Babies; the notes were for the legatees, she said, but God will forgive my pious little fraud. Most of the contents of the bag were sodden, the red ink washed off our exercises. A bunch of keys was recovered, not all of them house keys. The police had to find out what did they fit. The news leaked out from the police station – it was a porous establishment – that the key of the biscuit cupboard was found in her bag. ‘Well, that’s one good thing to come out of it,’ Miss Dowd said. ‘Who would have thought she would be so petty as to stoop to that? We were always hospitable to her, I’m sure.’

The shortbread had been kept in a sealed tin inside the cupboard, so it still had a snap to it, Rose told us. She washed up after the teachers till we left that summer. We were never lucky enough personally to set eyes on that tin, but Rose said it had a tartan pattern, like the ribbon on Lucifer’s topknot, and a picture of the Forth Bridge on the lid.

At the end of that year we moved to a new school, and Barry went to St Ambrose for a year and then to Ushaw to be holy, aged 13. Till spring the finding of the body was the talk of the place, but then the gypsies came back and the town settled into feuding with them, and it all receded into memory and myth. I suppose it was more or less known, who’d done it. Not the individual names; the whole Top Class fell under suspicion. But our teacher was known far and wide to be what Kinsella said she was, fit companion for a dog, and nobody was going to blight young lives. I overheard my dad say: ‘If it was boys you would flog the little bastards, but there’s girls involved, that are going to grow up to be wives and mothers.’ They abolished hanging soon after so nobody saw the fun in hunting us down. You couldn’t stop people pointing the finger of course. Nor stop her ghost walking On the Top, her dog whimpering after. She was seen mainly at dawn by those stumbling home from a lock-in. They said if she crossed your path you would suffer misfortune within a year and a day; but ask yourself, who doesn’t suffer ill luck on an annual basis? Nobody regards her, wailing in the lane, calling, ‘Mitch, Mitch!’ and ‘Where’s my bag?’ and ‘Where’s my darling boy?’

The school still stands but they have installed facilities. Heating is by oil. The front wall is glass so as you walk by you can see what goes on. They have built houses down Slaide Hill. You can stand on the top and look down into their kitchens and into their little squares of bald garden with the kiddies’ climbing frame and their slides. You can stand up there at night in the lane, and see their lights go out one by one, till you are left alone with no light but the stars and no sound but your boots squeaking on the wet leaves. There is a point at the bottom of the valley where the houses give way to waste ground, to a ravine where a few trees straggle, and a trickle of a stream runs between rocks. The summer leaves are thin and dry and when autumn comes you can see that black rubbish sacks roost in the trees like giant bats. If it is a Jubilee year we convene about the beginning of Lent to toast Kinsella in his hole. I remember as if it were yesterday, Rose stopping as we laboured uphill: ‘Here, I’ve something jelly on my foot.’ Peter saying: ‘That’s brain-paste; give us your foot, lovey, hoist it up.’ I remember his face, intent, as he plucked up a fistful of dock leaves, and rubbed the bottom of her shoe and wiped around the laces. Then he threw the leaves down, and away we went, Peter leading us, Rose’s hand in his.

We are now of an age when we would be drawing our pensions, if they hadn’t changed the rules. Of course we sold our souls but we don’t miss them. Peter says that around about 1965 the schools ceased to teach right from wrong, and that being so we are the last generation to have souls, in the old meaning of the word. But one day when it is the last day, it will all come out in the wash, you, me, Stella, the missing key: the five Hail Marys, the brain-paste, the tartan topknot and Kinsella in his hole.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.