For various reasons, many of them neither literary nor trustworthy, Sappho has always exerted a magnetic yet frustrating attraction on later generations. The frustration is due in part to the fact that her poetry is predominantly private, only a small amount of it has survived, and very little has ever been known about her. But it’s also safe to say we’re frustrated because a major feature of our limited knowledge has been, right from the start, the undeniable presence in her work of a clear erotic attachment (in whatever sense) to other women. Since the constant unstated – and, I suspect, often unconscious – determination has been to view her through the powerful but astigmatic lens of romantic idealism, this factor has always caused some embarrassment, not always acknowledged as such.

Her alleged lesbianism – a term coined from her island home of Lesbos – has provoked a series of uncomfortable reactions down the ages. As one papyrus fragment of a biographical notice from the second or third-century ce states, ‘she has been accused by some of being irregular in her ways and a woman-lover.’ Similarly a Byzantine encyclopedia, the so-called Suda: ‘She had three companions and friends, Atthis, Telesippa and Megara, and she got a bad name for her shameful friendship with them.’ Athenian comic playwrights had an overcompensatory habit of crediting her with (often anachronistic) male literary lovers. Horace wrote of ‘masculine Sappho’, the critic Porphyrio noted, ‘either because she is famous for her poetry, in which men more often excel or because she is maligned as having been a tribad’. Ovid, with characteristic witty elegance, enshrined this ambiguity in a single pregnant line: Lesbia quid docuit Sappho nisi amare puellas? – a question which can be read as asking either whether ‘Lesbian Sappho’ taught girls how to love, or how to love girls.

Sappho’s erotic predilections have remained a stumbling block for many, to be explained away or desexualised: witness the late 19th century’s interpretation (very popular for a while among scholars) of her as a kind of glorified headmistress running a high-culture finishing school. The very name Lesbos remains a local embarrassment today: despite the boost it gives to tourism, the island’s modern Greek Orthodox inhabitants prefer to call it by the name of its capital, Mytilene. Yet at the same time the increasing social, cultural and romantic acceptance of homosexual relationships has led to Sappho’s being established, along with Cavafy, as one of the Greek world’s most striking gay icons.

In this connection, the notorious unreliability of ancient Greek biographical details – the earlier the author, current wisdom has it, the less credible the guesses – has been a godsend, since it has allowed critics both to reject anything they regard as inconvenient, and to have great latitude in their own speculations. (The entry on Sappho in Lesbian Peoples: Material for a Dictionary, published in 1979, consists of a single blank page.) In fact we have quite a few nuggets of biographical information that seem arguably credible. It’s generally agreed that Sappho lived during the last decades of the seventh and the early years of the sixth century bce. She was born in the coastal town of Eresos, but spent most of her life in Mytilene. Her family belonged to the aristocracy; one young brother, Larichos, was a public wine-pourer, an exclusive office. Another brother, Charaxos, incurred scandal – and a poetic rebuke from his sister – through his much publicised liaison with a notorious courtesan. Their mother’s name was Kleïs; though the sources give no fewer than eight variants for her father’s name, the likeliest is Skamandros or Skamandronymos, which suggests a mainland connection with the Troad and Mount Ida. Sappho is also reported to have married a wealthy man from Andros, Kerkylas, and to have had a daughter by him whom she named Kleïs, after her mother. She was involved enough, as an aristocrat, in the vigorous class warfare of the island to be exiled for a while to Sicily.

Predictably, all this has been dismissed as fiction, some of it necessarily the work of Sappho herself (though why she should have chosen to invent a family scandal isn’t explained), and her alleged husband’s name and home are claimed as puns, suggesting a character called Little Prick from the Isle of Man. To complicate matters further, such conflicting attitudes have gone hand in hand with a near universal agreement since antiquity that she was a superb lyric poet. Solon in old age, on hearing one of her songs, wanted to get it by heart before he died. To Plato Sappho was the Tenth Muse. Romanticism has seldom had a more difficult case to handle. She is credited with nine books, mostly sorted into different lyric metres: the first book alone, consisting entirely of poems written in the Sapphic stanza, totalled 1320 lines (as one scribe noted on a papyrus fragment, when signing off), or 330 stanzas. We know that Book 9 was far shorter (possibly no more than 140 lines, though the text is uncertain); but if we estimate an overall total of some 10,000 lines we are unlikely to be far off. Of these, scraping together every sizable fragment, most of them without any sure context, we possess perhaps 5 per cent. This includes only one complete poem, the address to Aphrodite preserved by Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his treatise On Literary Composition, though papyrus fragments – in one case a very recent rescue operation from mummy cartonnage – have given us what would seem to be the larger part of at least three more. Even so, it is pretty certain that significantly more than 90 per cent of Sappho’s total output has been lost, and that the loss was near complete as early as the 12th century ce, when we find the Byzantine scholar Johannes Tzetzes lamenting it.

For the ancient world, Sappho’s work represented the summum bonum of lyric poetry, just as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey did of epic, and recent discoveries, if not quite achieving the level of the ‘Ode to Aphrodite’, are elegantly written and emotionally appealing compositions. The frustration of classicists at being deprived of so rich a literary legacy is understandable. The degree of minute scrutiny, the literary, dialectal, grammatical, syntactic and palaeographic high expertise, all concentrated on the smallest papyrus scrap of Sappho’s work rescued from oblivion, tell their own story. This phenomenon, in the work of such scholars as Dirk Obbink and the late Martin West, is both positive and creditable. But explanations of what led to oblivion in the first place, for a poet rated as highly as Homer, have not always been so objective. The temptation to blame moral disapproval has been irresistible. But such evidence as there is suggests rather a slow attrition of public interest – Sappho’s broad Aeolic dialect was a marked deterrent – leading to ever fewer copies being made: the road to extinction followed by so many other texts. The nearest Sappho’s work came to a Christian book-burning was probably during the Fourth Crusade of 1204, which indiscriminately destroyed the libraries of Constantinople.

How, then, do Diane Rayor, André Lardinois and the editorial staff of Cambridge University Press deal with this daunting situation? Not, at first sight, in the most encouraging manner. The subtitle attached to Rayor’s new translation of Sappho declares it to be ‘of the complete works’. If only! Lardinois’s useful introduction begins by noting that very little survives of Sappho’s poetry, which moreover ‘is often hard to read, because of its fragmentary state, and very difficult to interpret’. A new translation can offer no more than one scholar’s reading (to a great extent arbitrary) of other scholars’ editions. Sappho’s Aeolic Greek is extraordinarily difficult, and establishing the texts of her poems – especially those reconstructed from lacuna-ridden and often near illegible scraps of papyrus – is largely a matter of guesswork and speculative emendation. It’s a case crying out for a double-page presentation of English and Greek, the latter consisting, at the minimum, of the editor’s text from which the translator worked, and, for preference (given the exceptionally high degree of uncertainty), a basic apparatus criticus of variant readings and other suggested supplements. The opportunity was not taken here, perhaps in response to the usual mistaken notions of what the hypothetical general reader will put up with.

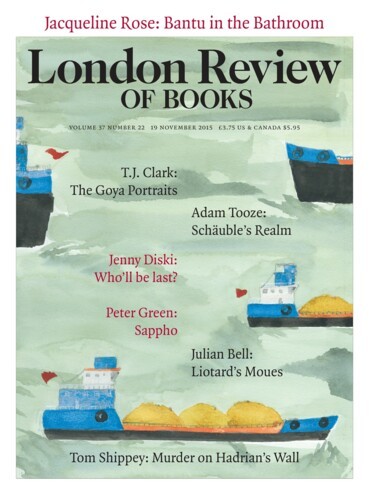

The front of the dust jacket, too, suggests a popularising approach. It’s devoted to a head-and-shoulders blow-up of the anonymous Italian lady from a Pompeian fresco, good-looking and auburn-haired, who, pen raised to lips and writing-tablet in hand, has so often, and so improbably, been identified as Sappho. At least since the Victorian period, the favourite visual notion of Sappho has been an elegant and attractive graduate, which sits well with the tall, non-individualised stereotypes labelled as Sappho on three Athenian vases from the sixth or fifth century bce. It’s true that normally we have no information about an ancient author’s physical appearance, but in Sappho’s case, unusually, we do have some. The papyrus fragment cited above states that ‘she seems in appearance to have been contemptible and unprepossessing, swarthy of complexion and very short.’ Dark-complexioned and small, with a central parting and bun, is a good description of many of the island’s women today; and for some years now an ancient mosaic portrait from Sparta has been known that is not only quite compatible with it, but has arrestingly individual features and carries Sappho’s name in large letters. The mosaic is remarkable for almost never being referred to by modern Sappho scholars: Lardinois is no exception, and he’s silent about the biographical fragment too.

However, what Lardinois offers by way of introduction is otherwise a useful and up-to-date survey. He reminds us that Sappho’s poems were songs, and that while we may have regrettably few of their words, their musical accompaniment on the lyre is entirely lost. He is sensible and wisely not too specific about the precise nature of Sappho’s undoubted homoeroticism, seeing it as by no means incompatible with heterosexual attraction, and draws a more likely ancient distinction between marital and passionate love – the first associated with Hera, the second with Aphrodite. Whether, as he also maintains, Sappho’s voice was consistently a public one, both among a close private circle of girls, or in the context of a formal chorus, seems more debatable, though it’s clear from her cultic hymns that she was a respected member of her aristocratic community. Lardinois suggests a comparison with the way in which the poet Alcman’s chorus members in his third so-called partheneion (maidens’ song) express their passionate devotion to their leader; but the famous male Socratic relationship of older lover (erastês) with adolescent beloved (erômenos) also comes to mind, a parallel that was already being drawn in antiquity.

Lastly, Lardinois does a brief rundown of the recent scholarly approaches to Sappho as an individual: as chorus organiser, teacher, priestess or dinner-entertainer. He supports the first, of which he sees the second as a misinterpretation; rejects the third altogether; and is uneasy about the fourth, though he concedes ‘that some of her songs were composed and performed for smaller audiences and more informal occasions’. This is all reasonable enough.But as he goes on to say, it is the powerful language, direct style and rich imagery of the poems themselves, even in the most fragmentary survivals, that have kept Sappho’s name alive and fuelled our perennial curiosity about her, and this at once raises the question of how far these and other literary qualities can be conveyed in a translation. The present work would seem to be a good test case. For sheer obsessional dedication to the task, which on and off has occupied her entire academic career, Rayor can have few rivals. Not only her present versions of Sappho’s work, but also anything she has to say about her guiding principles in making them, merit careful examination.

In her note on translation, she identifies her double goal as ‘accuracy guided by the best textual editions and recent scholarship, and poetry’. As far as the accuracy goes, ambiguities and all, she has, despite the occasional quibble (tolmaton, for instance, means ‘endurable’ rather than what ‘must be endured’), gone to great lengths to establish throughout the likeliest interpretation of Sappho’s often baffling Aeolic Greek. This is no small achievement. As far as plain meaning goes, hers is probably the most reliable, as it is the most up-to-date and exhaustive translation available. Where there are two possible readings (e.g. is Aphrodite poikilothron’ or poikilophron’, richly enthroned or subtle-minded?) she explains each in a note, so that even if the reader disagrees with her choice (as in this case I do, preferring the second) the alternative is ready to hand. As far as up-to-dateness goes, she’s managed to include, in a last-minute appendix, the so-called ‘Brothers Song’, about Charaxos and Larichos, the larger part of which was only discovered, edited from papyrus and published by Dirk Obbink as recently as 2014.

But what about Rayor’s blanket heading of ‘poetry’? ‘The experience of reading the translation,’ she says, ‘should be as close as possible to that of reading and hearing the Greek text,’ and should re-create that text’s ‘vivid and direct effects’, a high aim with which few would disagree. How does she go about it, beyond getting the meaning right? She retains, she assures us, ‘all specific details and imagery’, something I’d always assumed could be taken for granted. She claims to be concerned, beyond clarity and accuracy, with ‘the harmonious sound of the language’. The poems, she emphasises, ‘must be pleasant in the mouth and to the ear in order to accurately convey the Greek’, a claim which at first sight might seem a striking non sequitur, until she offers, as an example, an attempt to echo the ‘percussive alliteration and assonance’ of the original. In short, Rayor’s view is that the language should sound euphonious and poetical, and if it can be made to vaguely echo the Greek, so much the better.

How does Rayor deal with the crucial problem of structural rhythm, something absolutely central to Sappho’s work? We may have lost the music which formed its basic accompaniment, but the texts reveal their spoken or sung rhythms, above all in the famous Sapphic stanza, probably Sappho’s own invention, and one of the most subtly haunting rhythmic verse patterns ever devised: three hendecasyllabic lines, with slurred emphases on the first, fifth and tenth syllables, followed by one short line, and well captured in English by Swinburne:

So the goddess fled from her place, with awful

Sound of feet and thunder of wings around her;

While behind a clamour of singing women

Severed the twilight.

Surprisingly, Rayor’s sole allusion to the problem is in her declared intention to compensate (she doesn’t say how) for her disregard of ‘formal aspects, such as lyric metres that sound awkward in English’. For her, the solution is not to convert Sappho’s stanzas into a more English rhythmic equivalent, but to forget about formal metrics altogether.

The effect of this can be best appreciated by looking at the opening lines of the ‘Ode to Aphrodite’. Here is Rayor’s version:

On the throne of many hues, Immortal Aphrodite,

child of Zeus, weaving wiles: I beg you,

do not break my spirit, O Queen,

with pain or sorrow

Apart from a curious run of trochees in the first line, inappropriate and (one hopes) unintentional, this reads like a rather less ornate prose version than D.A. Campbell’s. It not only dispenses with the hypnotic rhythms, it is plain and, yes, a little awkward. How much can be restored by a shot (alternative reading included) at that carefully avoided lyric metre?

Subtle-minded undying Aphrodite,

child of Zeus, sly cozener, I beseech you

not with grief or longing to overmaster,

lady, my spirit

It is, indeed, as I would be the first to admit, a difficult rhythmic pattern to reproduce in a largely uninflected language, and I suspect the original required even more skill and imagination to create in the first place. Perhaps adequate translation of these fragments is ultimately impossible, and the hard demand that they make, first and foremost, is familiarity with their original Greek.

But background and context do help, and here Lardinois and Rayor score well: the first by trawling for every last brief fragment (reading them in sequence can leave an unexpectedly vivid kaleidoscopic impression); the second by sketching in the class-ridden political and social turmoil that lay behind Sappho’s life and her ultra-personal poetry. There is also the island of Lesbos itself: today, as in antiquity, large, variegated and wealthy enough to form an idiosyncratic world of its own. I lived there for more than three years, and kept coming up against things that reminded me of Sappho: above all, one magical evening, at dinner out on our terrace, when the moon that rose behind the wooded Lepetymnos mountain ridge above us was indeed, soon after sunset, as Sappho wrote, rhododaktylos, ‘rosy-fingered’, a curious physical phenomenon never experienced elsewhere, and not – it was suddenly clear – just a literary spin-off from Homer. In that brief moment we shared the unique vision of a poet who had seen, two and a half millennia ago, exactly what we saw now. Here as elsewhere, Sappho, passionate and imaginative, was still writing of what she had actually experienced.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.