I can’t remember a time when I didn’t provoke myself with impossible thoughts. To begin with I wouldn’t have known which were impossible and which not. But, curled up in a favourite dark place (I’ve always longed to be behind those deep red velvet curtains where Jane Eyre sits on the window seat, leafing through Bewick’s History of British Birds), or lying awake playing mind games in bed, you find out quite quickly that the imagination comes to an end in a deeply unsatisfactory answer to the question being put. Even so, I continued to try and tease out meaning for the words and the facts about life I discovered as I grew older and read more. The daily and nightly probing began around the age of six or seven, always ending at a wall or a miasmic fog in my brain. Looking back, I’m sure that it was tied up with my readings of Alice’s Adventures – in Wonderland but especially Through the Looking Glass – which easily brought dizzying thoughts to mind. What if the rabbit hole never ended? How to deal with the White Queen’s ‘Jam tomorrow’ which never comes today? And of course, the practice of believing six impossible things before breakfast. Which, if it did nothing else, at least told me that impossible things were there to be thought about.

Most things became easier the more I did them but my mental investigation of the creeping idea of infinity never got any further. Yet I couldn’t stop poking my metaphorical tongue at the metaphorical loose tooth, rocking it back and forth until the pain went beyond interesting and pleasurable. I’d devote every ounce of my being to the task of understanding the endlessness of infinity, as if one great push (birthing spasms, the fanciful Disney lemmings’ forward rush over the cliff to oblivion) would crack the problem open and I would find perfect understanding in the pieces that lay at my feet. I worried that the endlessness of infinity must come to a stop somewhere, because it hurt my brain to try to imagine that it didn’t. Later, more grown up in years though not in the things that worried me, I learned that the universe wasn’t infinite. Somehow. Then where was the edge of the universe? But that meant another universe, another edge, more and more, and there I was, back to infinity and dizzying brain ache. I simply couldn’t fathom, and for some reason thought I needed to, the parameters of the unending. I was using the wrong language, it turned out. Maths was invented to grapple with concepts that metaphor made murky. But I couldn’t think in that vital language. Just wasn’t my thing. So clinging onto the figurative to save my life, I vaguely grasped that the end of the infinite might be where death started. That required more probing. At first, when some knowledge of death’s ubiquity came to me, the main concern was the catastrophe of my parents’ death, hotly followed by adventurous orphan fantasies (Tick tock, Cap’n Hook, here comes an awfully big adventure with gnashing teeth), and a narrative which developed but never ended because I fell asleep.

Both infinity and death were beyond me. They defeated me, and although I came to know that everyone was subject to death, it was some time before the penny dropped that I, too, would eventually be part of the seething crowd of everyone who dies (‘I had not thought death had undone so many’). Melodramatic accidents were story material, but an ordinary death at the end of my life was an absurd proposition, and so remote as to be hardly worth getting a sweat up for. Even so, I’d lie awake trying to imagine being dead just as I tried to imagine stepping off the end of infinity.

It was easy enough imagining myself being dead, settled peacefully in my coffin, everyone sobbing into handkerchiefs, no unseemly snot in evidence, for their poor beloved dead child, but soon enough I realised that I’d got in my own way. Death is the end of you. Of me. There is no being dead. The body, the coffin, the tears were for those who were still alive. Without a notion of a holiday camp heaven, something I seem never to have had, I was left with a new and special kind of endlessness, like infinity, but without you. By which I meant me. You and then not you. Me and then not … impossible sentence to finish. The prospect of extinction comes at last with an admission of the horror of being unable to imagine or be part of it, because it is beyond the you that has the capacity to think about it. I learned the meaning of being lost for words; I came up against the horizon of language.

So it’s not as if I haven’t thought about death, yours, theirs, my death, all the time, now and back then. Like Gabriel in Joyce’s The Dead, I’ve imagined ‘the vast hosts of the dead’. And in my childish way, I understood Gabriel’s vertigo: ‘His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.’ But until my cancer diagnosis and the cautiously calculated prognosis last summer, death in all the forms it had come to me, or as I had worried it, was a description of the unreal. There has been grief in my life, though very little compared to many. A great grief, the loss of one of my oldest friends, my first husband and my daughter’s father, only came on me in 2011. A loss to me, whether we saw much of each other or not, of his being in the world. Your inevitable imagined death isn’t properly a grief until you look at it from the point of view of those who will remain alive without your being in the world. When the Poet expresses his sadness and forthcoming grief, it hits me as if I were him and suffering his loss of me. It is both a lesson in empathy and an indulgence in narcissism. I will, by then, not be suffering anything. Will not be. The pain and sadness that engulfs me at his distress is projection, a mirroring of another soul. Perhaps it is an exercise in the reality of love. How else can I conceive of my own death, even though I now know it will happen sooner rather than later? I did make one request to the Poet from beyond the grave: ‘I don’t much care about the funeral arrangements, but if I’m going to be buried, I want to be tucked up in a winter-tog-rated duvet. It doesn’t have to be exquisite winter snow goose down, though that would be nice. But I need a duvet. You know how much I hate being cold, and especially cold and damp.’ The Poet put his foot down. He hates waste and whimsical dishonesty. ‘You won’t be there to feel the cold and damp,’ he said. Tears came, just up to but not spilling over the lower lid. Mine. His. Sometimes it’s hard to tell. ‘I know I won’t. But now. I want the promise of a duvet.’ ‘Double or single?’

Nevertheless, the excruciating terror of the fact that I am in the early stages of dying comes regularly and settles on my solar plexus directly beneath my ribcage (called my coeliac ganglia, from which the sympathetic nerves in charge of the fight or flight response radiate, or called anxiety, or, if you prefer, my third chakra). There the terror squats, rat or raptor, its razor-sharp claws digging into that interior organ where all dreaded things come to scrape and gnaw and live in me. Still, so far, unabsorbed. Undigested. Dropping in on me, like the weighted lead of grief, when not expected. Give me medication, however unnatural, at least to round off the knife-edged talons scraping away at me. Give me some distance, some respite from this kind of pain as you do from the pain of cancer treatment, or cancer itself, or a broken wrist. It’s not a lesson I need to learn. I’ve known and recognised the underlying psychological causes, some of them anyway, enough of them. I own up to them and I really don’t need this solar grip to remind me of my fear. Death feels your collar when you’re going about your business almost as if nothing has happened, and when you are idling, wondering what there is to think about. Whoa, hang on, missus, the world has come to an end.

Negativity is my inclination, whether biochemical and/or environmentally produced. Looking at death as negativity, of everything gone, an absence, I get the image, from Psycho, of Hitchcock’s (or Saul Bass’s) shot of swirling bloody water draining into the plughole and transmuting into a teardrop in the corner of Janet Leigh’s open, dead eye. Her face crushed against the floor tiles, she can neither gaze into the abyss nor have the abyss stare back, because even the abyss is non-existent in the non-existence that used to be you. The abyss is merely a penultimate state of the ultimate.

I have ‘non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma’. I’m mystified by the term. By the negative term for its opposite. Non-small. A robust sort of cancer, then? Why not ‘large’ or ‘quite big’? It reminds me of Poe writing in The Pit and the Pendulum that his protagonist ‘unclosed my eyes’. Was ‘opened’ on the very tip of Poe’s tongue, but he couldn’t quite make the reach? I sense a pantomime audience howling ‘Opened! For god’s sake, Ed. Opened!’ Or did Poe choose this peculiar usage to unsettle the reader by throwing a net of the uncanny over the horrible moment of vision? But that can’t be the reason for the medical term ‘non-small’. Is it simply large-celled, but courtesy/custom/delicacy requires the euphemism? What need? Undead has quite another meaning. Where does this linguistic black hole get us? Non-alive, non-pretty, non-excellent. And up pops non-existent, just when I don’t need it. Hey nonny-no. In my third novel, Like Mother, the main character was called Nony for short – a baby girl born without a brain (although the narrator of the book). Non-existent. Nonny no.

One of the things I was very clear about immediately after my diagnosis as a canceree, was not wanting to be dropped into the ‘victim’ arena. Not ‘victim’, not ‘brave’, not ‘struggling’ or ‘battling’, or, worst of all, that awful designation, which chases us whatever we are doing or misdoing, being ‘on a journey’. When I began this memoir I anticipated with dread, and hoped to bypass, the crushing moment when I would first be described as ‘being on a journey’. Might have been King Cnut, for all the good that did. Quite a few people ignored me, as is their right, and jumped in anyway, launching my boat, giving me a pat on the back to get me going, firing the starter gun, swimming alongside me for a while, hoping I would stay the course, wishing me strength for the road I travelled, all of them knowing but not actually saying that journeys do end, that’s the point of them, and we all knew where this journey ended. Right at the start I was in a funk about the avalanche of clichés that hung over my head in a bucket that we would all, me included, tip up to cover me as if with pig’s blood at my first and last prom. (How do you do? The name’s Cnut, Carrie Cnut.) Clichés exist because they once worked brilliantly. They helped to universalise the intractably private, to keep a distance between what people wanted to say and couldn’t. They must have been alive then. Now they are either the deadening end of meaning or party favours to be played with. For some writers they are a springboard, perfectly placed to be rejuvenated, to renew or cut through their general use as thought-concealers. If people reach so readily for a cliché, it’s because there’s something they can’t say, or even think. When Beckett or Nabokov twists a commonplace into an oh-so-considered sentence, it too does the work of the uncanny. The too well known as unknown. I fucking love clichés.

Still, there is also the matter of just being accurate, taking the straightest route to the meaning you want. I am not on a journey, I repeat, testily. But as each of my treatments ended I found it grew harder to escape the platitude. The good cell/bad cell dichotomy of the body hosting cancer is difficult enough to avoid. The phoney spiritual analogy has become inevitable, everything that happens for more than a split second is a ‘journey’. It’s not our fault that time works for us in the way it does, or that the linear accelerates our lives. We ‘journey’ as we read books, watch films, look back at our past, imagine the future, even mindfully try to live in the always and only present moment while thoughts of what was, and is still to come, crowd our minds. Otherwise there’s silence, and that’s an option. Though not much of one for our narrating species. Can we even get dressed without a before and after, a beginning and end? Starting with your socks instead of your knickers doesn’t alter the fact of the matter: undone to done. And then the reverse. One, two, buckle my shoe. It’s inescapable. From one state to another, how can the journey not come to mind? That’s the price of living in time. Why should I mind so much? Why should I mind so much now? Because journeys end?

What’s strange is that the multitude of journeys we are all deemed to be on have become coupled with optimism, no matter that for most of human history a journey was always begun with the knowledge that it might not end well or in the right place. Ships were wrecked, brigands stopped and stripped pilgrims in their tracks, disease ended any thought of destination or arrival. The first time I experienced a journey with no destination was when the bailiffs came and took our stuff away, promising to return to evict my mother and me from the flat in Paramount Court. My mother, rising to the occasion, took my hand and dragged me along the streets shouting at me that now we were destitute, and were going to live ‘under the arches’ in Charing Cross with all the other tramps and beggars. (The music-hall song by Flanagan and Allen was ubiquitous then: ‘Underneath the arches/We dream our dreams away …’) I knew some of the tramps who had a regular route between the Rowton House workhouses and I hailed them as they arrived in Tottenham Court Road, where I played. But we weren’t heading directly to Charing Cross to claim our space: we were wandering. It was raining. I remember the dark pavement, watching my feet walking (my head down), the splashing of the falling rain, and for the first time being out and walking but without a destination. Before that if we went out we were always going somewhere, if only to a shop and then to return home. This was quite new and terrifying, we were just walking. Homeless, with nowhere to go. Of course, eventually, after my mother’s rage and fear had been walked off, we returned to our flat, still in possession until someone came and sorted my mother out with social security and a bed-sitting room in Mornington Crescent. Walking in the rain still makes me feel bereft, even though it’s only an echo of a fear that didn’t happen. ‘Underneath the arches/On cobble stones we lay/ … Pavement is our pillow/No matter where we stray/Underneath the arches/We dream our dreams away.’

But these days, being ‘on a journey’ assumes that you will reach your destination to a hero’s welcome, a happy ending, an apotheosis, something having been learned or earned, and approved. The slightest of efforts by an individual or a group is crowned with the completion of an inner journey that the actual journey (often not a journey) has nothing to do with. People wear T-shirts printed with their favourite charity’s slogan: ‘Let’s kill cancer,’ ‘Bring a homeless dog happiness and love.’ They run in circles, or cycle to the ends of the earth, swim the channel, the Atlantic ocean, several lengths of the local pool, climb Mount Everest, a Munro, a plastic wall, spell more words correctly than anyone else, and in November write a novel or grow a moustache. The money you ‘earn’ will provide goods for the needy, a drip in the stream of scientific research funds, and the effort you make will buff up your character. A journey seems always to be for the better. It ends in insight or excellence or positive change. But can Rolf Harris, formerly beloved entertainer, now convicted sex offender, be said to be on a journey as he slides down the fame snake to a cell in Stafford Jail? Still, if he makes a statement on his release, it’s likely he will tell us that he has been on a journey and learned lessons, perhaps even got himself straight with God, in readiness for the final journey. Has anyone willingly grasped the hellish consequences of their actions since Don Giovanni’s fevered acceptance of his murdered victim’s invitation to dine with him in hell?

Who lacerates my soul?

Who torments my body?

What torment, oh me, what agony!

What a Hell! What a terror!

Much as I hate it, the journey – that deeply unsatisfactory, often deceitful metaphor – keeps popping into my head. Like my thoughts about infinity, my thoughts about my cancer are always champing at the bit, dragging me towards a starting line. From ignorance of my condition to diagnosis; the initiation into chemotherapy and then the radiotherapy; from the slap of being told that it’s incurable to a sort of acceptance of the upcoming end. From not knowing, to ‘knowing’, to ‘really’ knowing; from being alive and making the human assumption that I will be around ‘in the future’, to coming to terms with a more imminent death. And then death itself. And… there is no and. Maybe it’s just too difficult to find a way to avoid giving the experience a beginning and an end. Except that it’s never over, cancer, until the fat lady pops her clogs. No one is ever cured of cancer, except technically. Even if I were to pass the magic five-year survival post, or go into remission, the possibility of a return of the cancer cells will always be there. Binary oppositions turn spatial. Whichever way I refuse to call it a journey, the pattern of a voyage is etched into every event. How can I avoid the idea that I am at the least on a journey from Big C to Big D (as everyone is, although the letter of the first stage may be different)? Why do I want so much to avoid the notion of a pilgrim progressing? What if I try it the other way? I’m standing still while the tests, diagnosis and treatments pass by me as if on a belt. This is not outlandish, the supermarket checkout, or The Generation Game, where the prizes roll along in front of you on a conveyor belt and you get to keep those you remember – a teas-maid! From first inklings, it is all outside me, moving at its own pace, while I observe attentively. Or like the journey I made by Amtrak around the US, watching the swiftly or sluggishly passing scenery through the window as I sat dreamily on a train. No, trains have destinations. Perhaps I’d better think of myself as sitting idly at a station, hanging out, while diagnosis, treatment and so on arrive, stop and depart. Me, I’m not going anywhere. Just watching the passing show. But it’s such an effort, wriggling away from the platitude while the journey taps her feet in the wings knowing where she belongs.

The end of the journey doesn’t come until you either die cancer-free of something else, or die of the effects of a regeneration of the cancer cells. Good and bad; from here to eternity, and from eternity to here. But I have been not here before, remember that. By which I mean that I have been here; I have already been at the destination towards which I’m now heading. I have already been absent, non-existent. Beckett and Nabokov know:

I too shall cease and be as when I was not yet, only all over instead of in store.

From an Abandoned WorkThe cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness.

Speak, Memory

This thought, this fact, is a genuine comfort, the only one that works, to calm me down when the panic comes. It brings me real solace in the terror of the infinite desert. It doesn’t resolve the question (though, as an atheist I don’t really have one), but it offers me familiarity with ‘the undiscovered country from whose bourn no traveller returns’. I’ve been there. I’ve done that. And it soothes. When I find myself trembling at the prospect of extinction, I can steady myself by thinking of the abyss that I have already experienced. Sometimes I can almost take a kindly, unhurried interest in my own extinction. The not-being that I have already been. I whisper it to myself, like a mantra, or a lullaby.

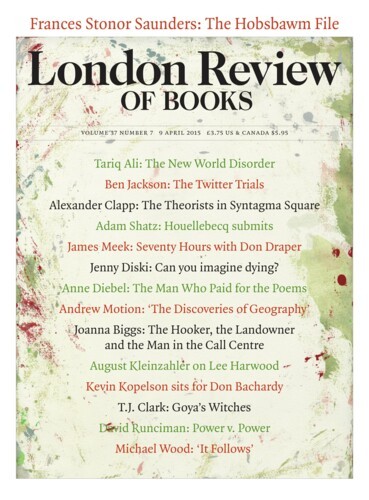

You can read the next instalment of Jenny Diski's memoir here (and the first one here).

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.