‘The British wrote cheques they could not cash.’

American Special Forces officer

In the morning , I left the village where I’d spent the night, the village where, in the ninth century, a famous king had beaten the army of a northern warlord. I climbed a steep path to a high plateau and walked along dusty tracks. There was gunfire in the distance. In the early afternoon I rested on a hilltop, on the ramparts of ancient fortifications whose shape was outlined in soft bulges and shadings on the slopes. Down in the fertile flatlands, I could see rows of the armoured behemoths Britain bought to protect its troops in Afghanistan from roadside bombs, painted the colour of desert sand and crowded around the maintenance sheds of a military base. There was a roar from the road below and the squeak of tank tracks. A column of Warriors clanked up the hill. The Warrior is a strong fighting vehicle. It can protect a team of soldiers as it carries them into battle. Bullets bounce off it. A single inch-thick shell from its cannon can do terrible damage to anything unarmoured it hits. But these Warriors looked tired. They came into service in the late 1980s, just as the Cold War they’d been designed for was ending, and Afghanistan has a way of diminishing and humbling military technology.

I’d walked the same route last year, leaving Edington after breakfast, walking round the edge of the military exercise area on Salisbury Plain and pausing at the Iron Age fort on Battlesbury Hill, which looks out over the British army’s Wiltshire estate. Since then most of the army in Afghanistan had come back to Britain, and an item of furniture had been added to the Battlesbury ramparts, among the cow parsley and purple clover: a bench. I was glad to sit down, as my pack was heavy. But the bench is also a shrine. When I came across it – this was in July – candles had been placed on it and a sun-bleached cloth poppy fastened to the back rest. It’s a memorial to six British soldiers: Nigel Coupe of the Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment, and Jake Hartley, Anthony Frampton, Christopher Kershaw, Daniel Wade and Daniel Wilford of the Yorkshire Regiment. All except Coupe, a sergeant and father of two children, were aged between 19 and 21. They died in Afghanistan in March 2012, out on patrol in Helmand province, when their Warrior triggered the pressure plate of a huge home-made mine. The explosion flipped the vehicle on its side, blew off the gun turret, ignited its ammunition and killed everyone inside.

The British army is back in Warminster and its other bases around the country. Its eight-year venture in southern Afghanistan is over. The extent of the military and political catastrophe it represents is hard to overstate. It was doomed to fail before it began, and fail it did, at a terrible cost in lives and money.

How bad was it? In a way it was worse than a defeat, because to be defeated, an army and its masters must understand the nature of the conflict they are fighting. Britain never did understand, and now we would rather not think about it. The troops are home from a campaign that lasted 13 years, including Iraq in the middle. They are coming home from their bases in Germany, too. The many car parks’ worth of mine-proof vehicles you can see from Battlesbury Hill, ordered tardily for Afghanistan at a million pounds apiece, will be painted European green and dispersed to other barracks.

David Cameron announced in December 2013 that the troops could come home because their mission had been accomplished. ‘The prime minister’s declaration of victory amounted to an instruction to the British public to forget about Afghanistan,’ Jack Fairweather writes in his powerful history of the war. The instruction was, it seems, hardly needed. The fall of Musa Qala in 2013, ‘once the focus of the British military’s anxiety about their standing in the world, barely registered in the national consciousness, and a desperate battle over Sangin in 2013 … attracted little attention’.

In 2012, when Frank Ledwidge was researching his book, which tallies the personal and financial cost of Britain’s Helmand campaign, he approached all six ministers who had held the defence portfolio since the start of the operation to ask what they thought its legacy would be. Not one – not Labour’s John Reid, now Baron Reid of Cardowan, or Des Browne, now Baron Browne of Ladyton, or John Hutton, now Baron Hutton of Furness, or Bob Ainsworth, or the Conservatives’ Philip Hammond or Liam Fox – was prepared to answer. For those not directly affected, the acceptable form of exculpation and remembrance involves obliterating any consideration of dead Afghans and folding the British war dead into a single mass of noble hero-martyrs stretching from 1914 to now. That, and more, bigger, shinier poppies.

The consequences of the Afghan war will linger. Neither the British in particular nor Nato in general kept count, but Ledwidge estimates British troops alone were responsible for the deaths of at least five hundred Afghan civilians and the injury of thousands more. Tens of thousands fled their homes. ‘Of all the thousands of civilians and combatants,’ Ledwidge writes, ‘not a single al-Qaida operative or “international terrorist’” who could conceivably have threatened the United Kingdom is recorded as having been killed by Nato forces in Helmand.’

Since 2001, 453 British forces personnel have been killed in Afghanistan and more than 2600 wounded; 247 British soldiers have had limbs amputated (the Ministry of Defence refuses to categorise the severity of these amputations on the grounds that releasing the information would help ‘the enemy’). Unknown numbers have psychological injuries.

Financially, the British operation in Helmand was under-resourced. It was, nonetheless, wildly expensive. Ledwidge puts the cost at £40 billion, or £2000 for each taxpaying household. Britain built a base in Helmand, Camp Bastion, bigger than any it had constructed since the end of the Second World War, occupying an area the size of Reading. It has now handed Camp Bastion over to the Afghan military which, at the time of writing, was struggling to prevent it being overrun by attackers. Everything the military did depended on the petrol, diesel and kerosene trucked in from Central Asia or Pakistan; one US estimate calculated that the price of fuel increased by 14,000 per cent in its journey from the refinery to the Afghan front line. In firefights, British troops used Javelin missiles costing £70,000 each to destroy houses made of mud. In December 2013, when they were packing up to leave, they had so much unused ammunition to destroy that they came close to running out of explosives to blow it up with.

Ledwidge adds in the cost of buying four huge American transport planes to shore up the air bridge between Afghanistan and the UK (£800 million), 14 new helicopters (£1 billion), a delay in previously planned cuts in the size of the army (£3 billion) and the cost of returning and restoring war-battered units (£2 billion). More contentiously, he includes the £2.1 billion spent on aid and development, not all of which was stolen or wasted – although much of it was. Ledwidge highlights the grotesque sums spent on providing security and creature comforts to foreign consultants: an annual cost of around half a million pounds per head. He was a consultant in Afghanistan himself, besides serving there as an officer. ‘A great many people, several hundred,’ he writes, ‘could be employed in Helmand for the price of a single consultant plus security team and “life-support”.’

Ledwidge estimates the cost of the British military’s bloodshed and psychological trauma – the amount spent on the ongoing treatment of damaged veterans, compensation under the recently introduced Armed Forces Compensation Scheme (AFCS), and an actuarial estimate of the financial value of human life – at £3.8 billion. He points out that, despite the AFCS, Britain’s care for its veterans falls short of the elaborate system in the United States.

An Afghan who sought compensation from the British in Helmand after losing his sight as a result of a military operation might expect a payment of £4500. A British soldier suffering the same injury would be entitled to £570,000, Ledwidge writes, the maximum possible under the AFCS. That’s not all there is to the compensation hierarchy. Ledwidge picks out one soldier acquaintance who lost his ability to communicate when a mortar shell brought a concrete bunker down on him, crushing his skull. He stands to get the maximum £570,000. Had the same man been injured in a car accident, the insurance payout would have been closer to £4 million, most of which would have been to pay for continuous care.

Ledwidge also tells the story of ‘Peter’, who served with him in the same reservist unit. A talented linguist, physically fit and a promising commander, he was seen as an ideal candidate for special forces, but was seriously injured in a bomb attack in 2006. The MoD told him, wrongly, that as a reservist he wasn’t entitled to a pension or compensation. He had to fight for three years to get them to acknowledge their mistake and pay the money owed him, while the MoD tried to show his injuries weren’t serious and to prove he hadn’t been a good soldier. He won. But not many soldiers, Peter said, had his access to good lawyers and a network of able friends. ‘If I had been alone,’ he said, ‘it was the sort of thing which could have driven me over the edge; after everything that had gone before, the pain and disabilities, this was the kind of thing that can break you.’ ‘Help for Heroes and charities like it’, he added, were ‘fig leaves for a government that wants to pass on the costs to an unaccountable charitable sector’.

Ledwidge is blunt about the division of responsibilities between society and modern volunteer soldiers who make a conscious choice to become warfighters.

The soldiers who are killed and wounded today are not victims – they are not the conscript ex-civilians of the First World War. They are professionals, willingly trained in the business of killing, and (by and large) well paid and well treated while they are soldiers … Servicemen are under no illusions as to the risks they sign up to … In looking so closely at the human costs of this war, the key point that must be borne in mind is not ‘How terrible! Those poor soldiers …’ Rather it must be a realistic and firm realisation: ‘We sent them, now we must take care of the consequences.’

I was in Kabul in November 2001 when the first British troops arrived in Afghanistan, a small contingent that didn’t hint at the great deployment to come five years later. I drove out to Bagram airfield to see them, but they’d been forced to hide from the media because the new Afghan masters of Kabul, the Northern Alliance, had made it clear they didn’t trust them. It was an unpromising beginning. I caught a glimpse of them in the distance on the tarmac, looking astonishingly clean-shaven, neatly turned out and weaponless compared to the ebullient bearded gunmen in pyjamas I’d been hanging out with.

It seems strange now, but it was still possible then to believe that their presence might be useful. It is easy to forget, after Iraq and Afghanistan, how high the professional reputation of the British military was in 2001. Whatever one thought of the political decisions to use them, however ugly and bloody the means, the services could say they had done what was asked of them by governments in the Falklands, in the Gulf War of 1991, in Kosovo, in Bosnia, in Sierra Leone. Their grim start in Northern Ireland eventually found a redemption of sorts with the Good Friday Agreement. Even those Britons who found the retaking of the Falklands, the bombing of Serbia and the deployment of British troops in Ulster repugnant could take pride in General Mike Jackson’s refusal, in Kosovo in 1999, to follow the orders of a hot-headed American general that could have led to an unnecessary skirmish with Russia.

It’s clear from these books, and from my own very short time with British troops in Helmand in 2006, that the military – or at least the army, which was the dominant service in Afghanistan – still recruits remarkable people, still trains them well, and provides them with a certain amount of good equipment. It’s also clear that institutionally it has been riding its luck for generations. What began at some point in the 20th century as an unsavoury means to an end – trying to use American military might to leverage the waning British military, with the end of maximising British influence – floated loose of its original aim. Preserving the means became an end in itself. The goal of the British military establishment became to ingratiate itself with its US counterpart not for the sake of British interests but for the sake of British military prestige.

Among other things, this involved increasingly desperate stratagems by the generals, admirals and air marshals to delude the Americans and, no doubt, themselves and their subordinates, that they were capable of keeping up with the relentless evolution of US tactics and the gold-plated technology that enabled it. Sometimes they were found out. After the Soviets introduced advanced anti-aircraft missiles in the 1970s, the RAF trained crews to fly low to avoid enemy radar, while the USAF took a technological approach, more protective of its aircrew, which Britain couldn’t afford. In 1991, half a dozen RAF Tornados were shot down by Soviet technology in Iraq. In the Falklands War in 1982, the Royal Navy, supposedly capable of going head to head with Soviet forces in the North Atlantic, was exposed as lacking the US navy’s multi-layered air defences, and was able to stop its aircraft carriers being sunk only by sacrificing smaller warships. Sometimes the delusion remained untested. During the Cold War, British troops in Germany trained for a war of manoeuvre against attacking Soviet divisions. The plan was for infantry to use anti-tank missiles to hold off the Red Army while British tanks manoeuvred for a decisive counter-blow. But the missiles British troops were supposed to use to blow up the advancing Soviet tanks would work only if they hit the tanks from the side. In his scathing contribution to British Generals in Blair’s Wars, a collection of 26 essays mainly by retired generals, Sir Paul Newton uses this story to mock the cliché that the British armed forces ‘punch above their weight’. ‘This was like telling a lightweight boxer he can only hit his oncoming heavyweight opponent by punching sideways … The army embraced the manoeuvre myth for it gave a veneer of plausibility to an otherwise militarily meaningless proposition.’

Both these traits – the upper echelons of the British military making American approval their primary goal, and the delusional exaggeration of British military capabilities – peaked in the 2000s. It was inevitable the two would clash; that at some point the desire to impress the Pentagon by using the Pentagon’s own resources as cover for Britain’s relatively low-budget military would conflict with America’s own interests, and end up damaging Britain’s military reputation more in Washington’s eyes than if the MoD hadn’t puffed itself up in the first place.

This is exactly what happened. When General Robert Fry, the MoD’s head of strategic planning, came up with Britain’s Afghanistan intervention plan in 2004, it was predicated on rapidly drawing down British forces in southern Iraq and shifting them to Helmand. Fry felt Britain had proved to the Americans how well its low-level, Northern Ireland-style beret-and-foot-patrol security approach worked in making a population feel secure without antagonising them. ‘As far as Fry was concerned,’ Fairweather writes,

the British had mostly accomplished their mission in Basra, which was relatively peaceful compared to Baghdad, and they were ready for a new challenge. He calculated that taking the lead in Afghanistan would enable Britain to swap an unpopular war for one that still enjoyed widespread support. Equally important, it would secure the British partnership with America in its limitless ‘War on Terror’, while avoiding the accusation of abandoning their allies in an hour of need … it didn’t matter if British power derived from the Americans; what mattered was that the British had power to wield, and [Fry] didn’t mind admitting that he rather enjoyed wielding it.

For the top echelon of the British army, there was also the attraction of the extra funds they could squeeze out of the Treasury while the troops were on active duty, and the prospect of keeping hold of regiments that would otherwise be axed. Like the disastrous decision to follow George W. Bush into Iraq in 2003, responsibility for the disastrous decision to send the army to Helmand in 2006 belongs to Tony Blair. And yet it takes two to indulge in unnecessary wars: the leader to tell the military what to do, and the military to tell the leader that it can be done. Ledwidge quotes Matt Cavanagh, who worked in Downing Street on the Helmand plan, as saying that the chiefs of staff told them taking on Afghanistan’s largest and potentially most difficult province ‘was an appropriate level of ambition for a country with the UK’s military capabilities and its place in Nato and the world’.

This was not the situation as the US saw it. Senior American officers in Iraq had become weary of British boasting of their superiority in counter-insurgency. What the Americans saw in Basra was worsening security and Britain losing control. What they wanted in 2004 was more British troops in Iraq, not for the troops already there to move to another country. They saw a defeated ally coming up with a cover story for retreat. ‘As far as the US was concerned,’ Fairweather writes, ‘these promises of troops for Afghanistan were mostly just a way to get out of Iraq while saving face.’

The September 2004 draft of Fry’s plan for the switch from Iraq to Afghanistan featured a graph showing British troop numbers in Basra smoothly falling away as numbers in Helmand gradually rose. There was a cross on the chart where the two lines met. This would have been fine if Basra had stayed quiet, but as the time approached when the first troops were due to land in Helmand, it became more and more evident that the British had failed to bring anything resembling order and justice to southern Iraq. Even before the Helmand operation started, it was obvious Britain needed more troops in both theatres. But it didn’t have enough even for one.

By 2005 British forces were well on the way to ceding Basra and the surrounding area to armed Shia groups; they would end up hunkered down and isolated behind the ramparts of their main base at the city’s airport. ‘To rectify the situation in Basra, the British would have to send more troops,’ Fairweather writes. ‘And yet their pivot to Afghanistan required them to do the exact opposite and withdraw. Rather than confront this gaping hole in their strategy, the British opted to carry on regardless.’

The beginning of Britain’s deployment in Helmand coincided with the belated realisation by British high command that their American patrons considered them to have been beaten in Iraq. Their much vaunted light-touch counter-insurgency skills had failed and the US was going to have to bail them out. This disaster made it even more important, from the British generals’ point of view, to persevere in Afghanistan. ‘We needed to prove that we remained a crucial strategic partner,’ Fry told Fairweather. ‘We needed salvation.’ In 2009, in a speech at Chatham House, the then chief of the general staff, Richard Dannatt, said:

There is recognition that our national and military reputation and credibility, unfairly or not, have been called into question at several levels in the eyes of our most important ally as a result of some aspects of the Iraq campaign. Taking steps to restore this credibility will be pivotal – and Afghanistan provides an opportunity.

Helmand turned out to be neither salvation, nor opportunity. Within weeks of their arrival in the summer of 2006 British troops were fighting for their lives. Twelve were killed in the first four months. Success in terms of their original, Blairite fantasy mission – to stamp out opium production and provide security for the transformation of Helmand into a modern, gender-neutral, democratic, tolerant, enlightened land where terrorists would find no nesting place, all in three years – was not possible. The real-world task the British military found themselves facing in Helmand was losing as few men and killing as few Afghans as possible before their inevitable retreat.

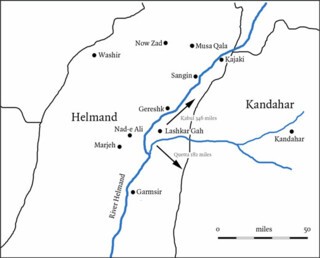

One immediate problem was all too familiar. The British forces wanted to have all the equipment the Americans had, but couldn’t afford quite enough of it, quite so up to date or quite so soon. Helmand is about the size of Croatia, a little smaller than West Virginia. The populated areas are concentrated along the River Helmand, with much of the rest being empty desert, and the British focused on the central districts, roughly the size of the Home Counties. But there was only one proper road, and as British troops came under attack in 2006, helicopters were the only effective way to move men and supplies around.

In the beginning British commanders had just eight transport helicopters, the big twin-rotor Chinooks. Gordon Brown was attacked in the British press for cutting back on earlier plans to buy more. In fact, Brown was responsible for telling the MoD how much it had to spend overall; the decision to cut helicopter expansion was taken by the service chiefs. Delays in getting bomb-proof vehicles to British troops in Iraq and Afghanistan happened for the same reason: the top brass and MoD officials hated to jeopardise the money they’d set aside to prepare for imaginary future wars, for aircraft carriers and fleets of air-transportable armoured vehicles. They knew that the same armchair warriors who shrieked in the press about the shortage of equipment in Afghanistan would be there to denounce them in ten years’ time for not having had the foresight to prepare for a crisis that demanded the overnight dispatch of tanks to Albania, or aircraft carriers to Norway. Nonetheless, the result was that the British military establishment put the preservation of its long-term budget ahead of the preservation of its soldiers in the field.

But the biggest military problem for the army, as it was attacked across the province by assailants using automatic rifles, machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades, mortars and home-made bombs hidden under or beside patrol routes, wasn’t about kit. It was more prosaic. It was about manpower. The initial headline deployment was 3500 British troops. Had the proportion of troops to locals been the same as in Bosnia, there would have been 28,000. And that 3500 covered everyone – the cooks, the mechanics, the medics. The proportion of men trained actually to go out on patrol, weapon in hand, was a mere one in five: about seven hundred, mainly paratroopers.

‘British troops were moved into Helmand before they had completed their task in Iraq,’ Hew Strachan writes in British Generals in Blair’s Wars.

The army was paying for its ‘can do’ mentality, its reluctance to challenge political direction which contradicted strategic sense, and its institutional fear that if it were not used it would be cut. Between 2006 and 2008 it fought two campaigns without being able to resource either of them properly … These were limited wars but they required masses of troops, and Britain did not have them.

The Afghan army in Helmand was non-existent. The local Afghan police were, on the whole, criminal. The Helmand director of education was illiterate. Shunned by the aid agencies, without the skills or resources to manage reconstruction on his own, under conflicting pressures from military chiefs in London, from Downing Street, from Nato commanders in Kandahar and Kabul, from US generals and from Afghan officials, the British commander, Brigadier Ed Butler, deployed small units of troops to far-flung, hostile towns where they were besieged by ephemeral bands of Pashtun gunmen. The commander of the paratroopers, Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Tootal, had imagined himself making a hundred-man foray into deep Helmand, away from the relatively quiet towns of Lashkar Gah and Gereshk, once a month. In the end, in the first month, he sent his men out on a dozen raids. The defence minister John Reid said he hoped the operation could be carried out without a shot being fired. In those first six months, Tootal’s men fired half a million bullets.

By September, Fairweather writes,

Pockets of UK troops were stationed in half a dozen outposts across the province, most of them under steady attack … These ‘platoon houses’ of only a few dozen men relied entirely on helicopter support to bring in food and water. Some weeks, when desert storms raged or [attackers] prevented helicopters from landing with small arms fire, the soldiers’ supplies dwindled to a bottle of water a day per man. They had little choice but to raid local marketplaces.

I spent a few days in Gereshk in 2006 with the first company of paratroopers stationed in Sangin.1 After a period of tranquillity, they’d been attacked five or six times a day. About every seventh man in the original unit of 65 had been killed or wounded. Among the dead was a Pakistan-born British Muslim soldier, Jabron Hashmi, a signaller attached to the Paras. Some men had lucky escapes: one was hit but saved by his chest armour; another was struck in an ammunition pouch he was wearing; another’s machine gun was hit while he was firing it. Combat engineers had to build fortifications under fire. The shortage of manpower meant that the troops not only had to devote their efforts to protecting themselves, they also wreaked terrible destruction around them in the process. At one point a B-1 bomber, designed to penetrate Cold War Soviet air defences, was used to drop bombs on Afghans shooting at the British in pyjamas and plastic sandals. One sergeant told me he’d called in an air strike within three hundred yards of his own position.

The soldiers I met fell into three groups. The young recruits were mostly exultant at having survived their battle initiation – they had joined the army to fight, after all. Their point of reference was the Paras who fought in the Falklands; they’d proved themselves, they told me, to be the equals of their regimental forebears. Then there were the officers, the major commanding the company and his two lieutenants. They were wary and diplomatic. Without playing down the scale of the fighting or the losses, they made it sound as if they’d always had the situation under control. This was difficult, as emails sent from Sangin by the major, Jamie Loden, had already been leaked to Sky News and told a more anxious story: ‘We are lacking manpower. Desperately in need of more helicopters.’

The most clear-eyed and honest assessment of what was going on came from the NCOs, the corporals and sergeants, seasoned professional soldiers, the backbone of the army. They were the ones who were prepared to admit how hard it was to put to the back of their minds the fact that a young fellow soldier, whose fiancée was expecting a baby, had just stepped on a mine and lost both his legs. They understood quickly, and weren’t embarrassed to say, that the people attacking them were local, not outsiders; and that all the British army’s efforts were being drawn into self-protection. The operation’s justification was itself; the men drew strength from protecting one another. I went out on patrol with them several times. We tramped silently through the cold looks of Gereshk market and crossed in thin-skinned vehicles the sudden boundary between the lush green plots of the irrigated zone and the powdery sand of the desert, where families will keep a single forlorn plant watered in the dirt in front of their mud-brick houses as a kind of pet. The Paras were reduced to the mere demonstration of their own existence. ‘You need more fighting troops out here,’ a sergeant told me one day, as we headed back from patrol in the back of an open truck. ‘This is such a big area to cover, the Helmand province. If you want to dominate the ground, you need a bigger force.’

By October 2006, Sangin market was a heap of rubble, many people in Musa Qala had been made homeless, and the entire civilian population of Now Zad had fled. More British troops were sent as the Basra garrison was drawn down, but attacks on them increased. In 2008 almost half of all attacks on Nato troops in Afghanistan were in Helmand. By March 2009, the British were being hit with a dozen bomb attacks every week. Eventually the Americans sent in the Marines, bailing Britain out a second time. Blair and the generals had bitten off far more than the British armed forces could chew.

In a way, the arrival of the Marines left British troops in a worse position. They were still under pressure from the chiefs of staff, Downing Street and the British media to uphold an ideal of military valour and efficiency alongside the Americans, but they were now effectively subordinate to US plans. Not only did the old disparity of firepower between the two members of the alliance remain; the Americans, inspired by the apparent success of their ‘surge’ in Iraq, were keen to implement the same aggressive policy in Afghanistan. The British, who, left to their own devices, might have cut deals with their attackers and quietly slipped away, were obliged to go along with it.

Things came to a head in the summer of 2009, in an operation called Panther’s Claw, designed to clear and hold the mine-infested dirt road between Lashkar Gah and Gereshk. One of the main British unit commanders, Lieutenant Colonel Rupert Thorneloe of the Welsh Guards, feared he had neither the men nor the equipment to do the job. The British had so few helicopters, and so many home-made bombs had been planted in the territory, that his men were having to hand-clear mines just to resupply outlying garrisons with rations. But he followed orders and went ahead. On 1 July, his vehicle was blown up by a concealed bomb. He was the most senior British officer to be killed in action since the Falklands; a teenage soldier died with him. Three days later, a soldier was killed by a rocket-propelled grenade and two more by bombs. By the end of the week, the British had lost four more men. In one two-mile stretch of road, attackers had planted 53 bombs. Another officer was killed in the accidental crash of a Canadian helicopter. Then, in a remote outpost called Wishtun, stripped of its most experienced troops to support Panther’s Claw, a chain of linked bombs killed a young rifleman and injured six others. While the stretcher-bearers were trying to find a bomb-free landing spot for the medevac helicopter, another bomb chain went off, killing four more men. In ten days, 15 British soldiers died.

British Generals in Blair’s Wars kicks off with a vigorous attack on Tony Blair by Jonathan Bailey, who retired from the army as head of doctrine in 2005.2 But towards the end of the book, as the commanders who served in Afghanistan get their say, the dominant tone is of anger towards the Ministry of Defence and the army itself, which emerges as an organisation incapable of learning except by years of trial and error when real wars come along. The colonels and brigadiers aren’t envious of the American military’s budget or its technology so much as the esteem it gives to intellectual analysis, education and the public discussion of new ideas.

The army that went into Iraq and Afghanistan was hobbled by its lack of back office support. Defence Intelligence, the MoD’s in-house intelligence agency, had got rid of its linguists. The MoD’s main research centre was privatised in 2001. In the US, military students’ unclassified research is freely published online; the British equivalent is kept hidden. When the British criticised the Americans’ ignorance of counter-insurgency in Iraq in 2005, the US took it to heart; two senior officers, including David Petraeus, set about updating the American military’s counter-insurgency doctrine. But complacent Britain saw no need to do the same. Alexander Alderson, a colonel who served in Baghdad, points out that in 2008 the Americans, the Australians and the Canadians all had centres for studying counter-insurgency. Britain didn’t. The other nations, Alderson writes, ‘were mystified why, given the obvious difficulties the UK had had in Basra, we had done nothing about it … Sadly, by 2008, the UK was not just the junior coalition partner to the US, but the junior intellectual partner as well.’

Paul Newton’s article is typical of the barely restrained bitterness of mid-level generals towards an army damaged less by budget cuts than by institutional denial of the need to adapt, going back, in his case, to Ulster: ‘Having taken command of an operational brigade that was living off its reputation for, rather than a real proficiency in, the craft of counter-terrorism, leads me to suspect that when informal learning ends after the army leaves Helmand, the primary driver for military adaptation, as well as the folk memory, will rapidly fade.’

Alderson got to set up a counter-insurgency centre for the British army in 2009. This might seem like progress of a kind, were it not for powerful evidence that the war the British and the Americans fought in Helmand wasn’t a counter-insurgency at all. I’ve avoided using the word ‘Taliban’ up till now. That isn’t because they don’t exist, or didn’t play a role in attacking British troops in Afghanistan. They do; they did. But Mike Martin’s extraordinary book, based on interviews with 250 people, almost all of them Helmandis, lays out the wrong-headedness of the mainstream Western characterisation of the situation in Helmand from 2006 to the present day as a ‘Taliban insurgency’ against a ‘legitimate government’, which the British were helping stand up after a long, tyrannical deviation from civilised norms.

Martin, a Pashto speaker, a British officer who served in Helmand in the late 2000s and a protégé of both Alderson and Newton, argues that ‘insurgency is a pejorative term, one that is useful to governments in establishing their legitimacy or that of their allies and in defining their enemies.’ Martin believes that the conflict in Helmand should be seen as ‘a continuing civil war’. Because the British were ignorant of what was really going on – due, in large part, to their short six-month tours of duty and lack of linguists – they were manipulated into becoming pawns in long-running conflicts over land, water, drugs and power between local leaders.

British commanders in Helmand always knew they began with two big handicaps, over and above the shortage of men and helicopters. One was that the British army has a history of invading Afghanistan. The other was that they came to Helmand with the intention not only of making it a safer, better place, but of destroying the mainstay of its economy, opium farming. Afghanistan was (and still is) the source of most of the world’s heroin, and Helmand is the centre of poppy-growing. Most farmers depend on it for their livelihood. It was as if an Afghan army had come to Scotland proclaiming that they would make it better, and that their first step would be to blow up the distilleries and oil rigs. In fact, Britain underestimated the first factor, and misunderstood the second.

Hostility towards the British among the Pashto-speaking Pashtun tribes of Helmand goes back to the early 19th century. The two dominant groups in the province are the Barakzai, powerful in Gereshk and the central lowlands, and their rivals the Alizai, whose heartland is in the more mountainous northern areas of Musa Qala, Sangin and Kajaki.3 After the British first invaded in 1839, they managed to alienate both tribes by removing the Barakzai king of Afghanistan, Dost Mohammad, but failing to protect the Alizai from the predatory tax collectors the Barakzai had installed. When the Alizai killed one of the tax collectors, the British sent troops against them. The British were eventually driven out and slaughtered and Dost’s rule restored, but the resentment towards them remained. After Britain invaded again in 1878, they were attacked at Gereshk by an Alizai army. Although Britain tried to use Barakzai proxies against them, the two tribes formed a brief one-off alliance and defeated Britain at the Battle of Maiwand, in 1880.

Britain eventually won that war, but the Helmandis still celebrate Maiwand with the fervour and freshness Scots bring to celebrations of Bannockburn, Serbians Kosovo Field and Russians Stalingrad. The British were hated in Helmand before they’d fired a shot, although generally the locals were too polite to say so. The actual reason Britain deployed to Helmand rather than Kandahar, the main city of southern Afghanistan, was that the Canadians had bagsied Kandahar, but Helmandis had no way of knowing this. The reaction to the British arrival was one of astonishment. Fairweather quotes Ashraf Ghani, now the country’s president, who predicted: ‘If there’s one country that should not be involved in southern Afghanistan, it is the United Kingdom. There will be a bloodbath.’ A popular local assumption was that the British had come for revenge. When, within weeks of their arrival, the bombs began to fall, the Helmandis didn’t see it as the British defending themselves – even though the attackers were, in the main, Helmandis – but as confirmation of Britain’s thirst for vengeance. ‘From the perspective of the Helmandis,’ Martin writes, ‘the historical enemy had just turned up for round three.’

As for opium, British forces, along with the civilian reconstruction and advisory teams they were there to back up, could hardly ignore the crop’s centrality to the Helmand economy. But that understanding was only a small part of the picture. In Martin’s analysis, seemingly cynical yet backed up by his heroic research, each outside intervention in Helmand – whether from an Afghan government in Kabul, from Moscow, London, Peshawar, Quetta or Washington – has two negative effects, whatever benefits it might bring. First, it lays down new local grievances on top of old ones that remain active. Second, it gives tribal barons new sources of funding and new ideological guises they can exploit in order to settle those grievances. These guises, these idealistic labels concealing the striving for clan or tribal advantage – the ‘mujahedin’ label, the ‘government’ label, the ‘communist’ label, the ‘Taliban’ label, even the ‘pro-British’ label – are what Martin calls ‘franchises’. Agencies from beyond Helmand give local big men money and/or weapons to act in their name, and a cause by which to justify their actions. The local leaders then bend this external support to personal ends.

The joint Afghan-American project to irrigate the Helmand valley in the 1960s, for instance, in the pre-opium days, was a boon to the region in that it brought bigger crops. It also brought grievances. The Alizai were angry (they still are) that the dam central to the project, at Kajaki, was on their territory, while the benefits flowed to the Barakzai on the plain. These events also marked the beginning of the era when such local grievances would be fought out through the adoption of labels of convenience. Although Martin says little about this moment, it seems possible that in those days there was genuine idealism and hope for change in Helmandi society. But the arrival of reformers from outside – the arrival, essentially, of a Western idea of central government – also gave powerful Helmandi tribes, families and opportunists the chance to pursue or suppress local grievances over land and water by adopting the labels, or ‘franchises’, that Martin describes: ‘pro-government’, ‘communist’, ‘anti-government’ or ‘Islamic’.

Throughout the communist era and the Soviet occupation, the opportunities for Helmandi barons to adopt franchises became more diverse, specific and lucrative. In the early days feuds could be expressed by support for national factions of the Communist Party: the woman-subordinating traditionalists of Khalq, or the more cosmopolitan, gender-liberal communists of Parcham. Later, the mujahedin era offered a new set of labels.

Martin describes the mujahedin groups set up in Helmand in the late 1970s to fight communism as entrepreneurs who saw an opportunity to get access to the stream of money, weapons and propaganda emanating from Muslim idealists in Pakistan and, later, from the CIA and the Gulf states. Starting with a small seed-group of armed men and a demonstrative skirmish or two, they would approach one of the Peshawar-based mujahedin groups, mainly the Muslim Brotherhood-influenced Hizb-e-Islami or the more traditionalist Harakat-e-Enqelab-e-Islami, seeking patronage.4 With Hizb or Harakat support, they would attract more fighters. With more fighters, they would attract more support, and so on.

When the communists fell, these mujahedin franchisees – besides fighting socialism, they had become the kingpins of the new opium economy – rebranded themselves as ‘government’, and set about plundering, racketeering and squabbling. With the coming of the Taliban, the ‘government’ fled and the Helmandis were largely left to their own devices. When the Taliban was pushed away in 2001 the ‘government’ franchisees soon re-established themselves. These were the hated mayors, policemen and secret policemen – who set up countless illegal checkpoints to extract tolls from travellers, stole their rivals’ opium and tricked Western troops into sending their personal enemies to Guantánamo – that British forces spent eight years fighting and dying for.

The British, Martin explains, were never fighting waves of Taliban coming over the border from Pakistan: they were overwhelmingly fighting local men led by local barons who felt shut out by the British and their friends in ‘government’ and sought an alternative patron in Quetta. The Taliban provided money, via their sponsors in the Gulf, and a ready-made, Pashtun-friendly ideological framework the barons could franchise. Since the British were hated even before they arrived, recruitment of foot soldiers was easy.

The degree to which outside powers get something in return, according to Martin, is in direct proportion to their knowledge of Helmand and the personal histories of its leading families. The British and Americans, accordingly, got played; the Pakistan-based Taliban, who were more familiar with the territory, did better out of allowing the Helmandis to attack the British under the ‘Taliban’ brand. But their success was limited. When, around 2010, the Quetta Taliban tried to enforce the strict operational control over the Helmandis fighting in their name that the British fantasised they’d always had, it didn’t work. The Helmandi ‘Taliban’ were following their own agenda.

This sketch oversimplifies the true situation in Helmand as Martin describes it. And Martin’s interlocutors told him that he had only begun to grasp the province’s tangled realities. No story shows the labyrinthine workings of Helmand politics better than that of the Akhundzada family, scions of an Alizai clerical dynasty from northern Helmand. Nasim Akhundzada formed a mujahed band in 1978, seizing Musa Qala from the Kabul government the following year, killing hundreds of people in the process. He spent the next few years fighting under the ‘Harakat’ brand against his local enemies in the north, making strategic marriages, buying popular support through handouts and small building projects, and developing his control over the opium crop. Because he was a ‘Harakat’ mujahed, meanwhile, the communist secret police gave him money in exchange for fighting ‘Hizb’ mujahedin; the police didn’t realise he wasn’t fighting them because Hizb were his enemies, but that they’d badged as Hizb because they were his enemies. The meaninglessness to Nasim of his ‘Harakat’ affiliation is shown by the fact that he sent his opium for processing to labs run in Iran by Hizb, his supposed rival. In 1990, what remained of the post-Soviet government in Helmand split into warring Khalq and Parcham factions, which formed alliances with Hizb and Harakat respectively. ‘The two halves of the “government” were openly working with opposed “mujahedin” groups, against each other,’ Martin writes. ‘The fluidity with which two bitter enemies, Hizb and Khalq, could align with each other left many to conclude that the spirit of the jihad had been hopelessly corrupted.’

At this point, Nasim was assassinated, to be replaced by his brother Rasoul. Three years later, after a grotesque sequence of double-crossings, gunfights and lootings, Rasoul and his allies chased the ‘Khalqi-Hizb’ factions out of the province and the Akhundzadas got their first taste of gubernatorial power. In 1994, Rasoul died and was replaced by his younger brother Ghaffour. After the Taliban took over, Ghaffour fled, but the Taliban assassinated him in Quetta, leaving Rasoul’s son Sher Mohammad Akhundzada to pick up the family business and its many feuds.

In Pakistan Sher Mohammad made friends, and an indirect tie of marriage, with Hamid Karzai. At that time Karzai was an obscure but politically ambitious Pashtun chieftain’s son. In 2001, when the Taliban were evicted from Afghanistan and Karzai became national leader, he and his US patrons saw to it that Sher Mohammad became the new governor of Helmand. Other former mujahedin commanders, noted for their rapaciousness and seniority in the opium business, returned in his wake to take over the reins of the Helmand ‘government’. The White House and the Pentagon were focused on invading Iraq and capturing Osama bin Laden: they had little interest in local politics or narcotics in an obscure corner of Afghanistan, except in so far as the local bigwigs might help them hunt down al-Qaida.

The small contingent of US special forces based in Helmand between 2001 and 2006 didn’t mean to poison the well for their successors, but that was what they, together with the mujahedin commanders, did. The commanders used the Americans to target their enemies, and get US bounty money, by branding their rivals ‘Taliban’ and having them sent to Guantánamo. One was beaten to death inside the American base. International poppy-eradication efforts were deliberately directed by commanders against rivals’ fields. The commanders attacked one another. They fought over control of the checkpoints used to shake down travellers. They stole opium from one another’s clients. They stole the opium harvests of the poor. They ruthlessly preyed on anyone whose safety wasn’t guaranteed by the big protection networks. They stole land. They dragged the Americans into a long-running quarrel over who controlled Sangin bazaar. In 2005 dozens were killed in a gun battle in Lashkar Gah when a lieutenant of Abdul Rahman Jan, the notoriously bullying ex-mujahedin commander who’d become chief of police, attacked a Sher Mohammad drugs convoy. Another big commander, Mir Wali, became the head of the Afghan army’s mainly illusory 93rd Division, for which he reaped government salaries; he ingratiated himself so skilfully with the Americans as to give the impression to his rivals that he was untouchable.

In 2004, just as Fry was preparing his plans for the British deployment, two processes began that would undermine it further. First, in reaction to their oppression by ‘government’ commanders and the careless harshness of the American forces apparently sponsoring them, ordinary Helmandis began to reactivate dormant ‘Taliban’ networks. Attacks on ‘government’ officials – that is, predatory ex-mujahedin and ‘police’ – and on the Americans increased in number. The Taliban’s credibility had been low when they were driven out in 2001: they’d failed to deal with a drought, they’d mysteriously banned the cultivation of opium but not its sale, they’d built nothing for the people except madrasas, and they were operating an obnoxious system of conscription. It took the coming of the Americans and the return of the mujahedin commanders to make the Taliban look good by comparison.

Second, the UN, with the best of intentions, launched a programme to disarm and retire the commanders. Mir Wali was sacked as head of the 93rd Division; later, Abdul Rahman lost his job. Sher Mohammad might have kept the governorship – Karzai and the Americans wanted him to stay – but to the incoming British, he was the spider in the centre of the web of everything corrupt and wicked in Helmand, and they insisted he be sacked. In December 2005, Karzai let him go. Ledwidge, Fairweather and Martin have different takes on the proximate cause of Sher Mohammad’s dismissal – the discovery, by a national Afghan police unit close to Britain, of nine tonnes of opium in his possession, enough to make nearly a tonne of heroin. Ledwidge reports Sher Mohammad’s claim that it was all a misunderstanding. According to Fairweather, the governor’s agents had legally seized the drug and reported it to a local American commander, who’d passed the information to Western embassies in Kabul. The next day the US officer went to inspect the haul before it was burned. He was just leaving when the British-sponsored team arrived. The American, Jim Hogberg, believes the British used his tip-off to entrap Sher Mohammad. According to Martin, whose information comes from a former Taliban commander in Lashkar Gah and an elder in the Alizai, Sher Mohammad’s tribe, the heroin was not ‘legally seized’, but simply stolen by Sher Mohammad from his then enemy and business rival in the drugs trade, Mir Wali.

Cast out of the ‘government’ system, with all its opportunities for patronage and abuse, Sher Mohammad and the other commanders lost no time seeking alternative backers. They turned to the Taliban in Quetta. The existing local uprising against the oppressive power of the ‘government’ barons, which the Taliban had embraced, was suddenly joined by those very barons and their sprawling client networks. Sher Mohammad, Martin writes, ‘ordered his commanders to begin fighting the British under the Taliban franchise’.

It is difficult to imagine how the situation for the British could have been less favourable. Their lack of resources, their lack of local knowledge, their mandate to attack the Helmandis’ chief means of livelihood and the popular belief that they had come for revenge would have been bad enough, without an indigenous, Taliban-branded revolt against marauding ‘government officials’ being joined by those very ‘officials’ and their men. To make matters worse, only the top commanders had been taken out of government – those who, no matter how badly they behaved, had the ruthlessness, negotiating skills and authority to bring whole communities on side. The British were left to try to work with – to try to fight for – the second-tier ‘government officials’, often the least capable and most rapacious lieutenants of the dismissed commanders. ‘Taliban commanders specifically mention the fact that the British were affiliated with the communities or commanders who had previously been oppressing them,’ Martin writes. ‘From the British point of view, they were not affiliated with anyone apart from the government, but it took time for them to realise just how partisan and non-cohesive the “government” was in Helmand.’

Counter-insurgency as practised by Nato in Afghanistan, Martin writes, had three parts: protect the population, improve governance, develop the country.

Looking at it from the Helmandi perspective, the population might well ask, ‘how can you protect us from ourselves when we are resisting you?’ This idea was recognised during the Soviet era as well. Neither the Soviets nor [Nato] had conceptual space in their doctrines for large sections of the population resisting them, so instead they were painted as Maoist-style insurgents from outside who were terrorising the community.

Martin’s is a bleak book, ending with the suggestion that, behind the fighting, the real crisis in Helmand – likely to draw in Iran as much as Pakistan – is the worsening shortage of water. The book is also, inevitably, incomplete. The remorseless focus on the actions and words of the Helmandi puppetmasters, of tribal elders and fighters and drug barons and policemen, crowds out other voices. Women are silent, and it is hard to believe that in all Helmand there aren’t actors who are playing on an Afghan national stage, or who seek to transcend blood feuds and tribal politics. But An Intimate War is the work of a wise and patient scholar. Although it is about how poorly Britain understands Afghanistan, it is also, implicitly, about how poorly Britain understands Britain; about how, that is, Britain became the country it is in 2014, with its schools and hospitals and bareheaded women, its weak ecclesiastical law, its gunlessness, its multiplicity of roads, its sewers, its literacy. A thousand years passed between the famously literate King Alfred of Wessex’s victory at the battle of Edington in Wiltshire and England’s introduction of universal education. Afghan children shouldn’t have to wait that long; it would be wrong to suggest Afghanistan is at some pre-set historical ‘stage’ which it would be better enduring in isolation. Afghanistan needs help, encouragement, advice, money. It’s just that next time we think about military intervention in a foreign country that hasn’t attacked us, it might be worth running a thought experiment to work out at exactly which moment, in the many internecine conflicts that have afflicted the British Isles, our forebears would have most benefited from the arrival of 3500 troops and eight helicopters, and for which ‘side’ those troops would have fought.

According to Martin, Helmandis believed deeply in the natural cunning of the British, so much so that the former chief (actual) Taliban commander in Helmand, the late Mullah Dadullah, was known as ‘the lame Englishman’ on account of his one leg and his extreme deviousness. For this reason people found it hard to account for Britain’s conduct in Helmand. There were two possibilities: the less likely was that the British were naive and ignorant. The favourite explanation, widely and sincerely believed, was that, secretly continuing to exercise imperial control over Pakistan, they were working hand in hand with the (actual) Taliban to punish Helmand, and that the Americans were trying to stop them.

Martin tells the story of one ‘Taliban’ commander who believed he’d been recruited by the British because, not knowing he was ‘Taliban’, they’d given him a card allowing him to claim compensation for damage to his house. His conviction was strengthened when his house happened to be searched by courteous British troops who somehow failed to find his hidden Kalashnikov. While he was waiting for what he imagined to be the first contact from his new British employers, he was killed by British special forces. Proof that the conspiracy theory was wrong? No, said his men; he was killed by the Americans, because he was on the books of their enemy, the British. The British and the Helmandis lived side by side for eight years, but didn’t get to know each other.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.