Writing to his friend Stephen Bann, then a graduate student, in 1964, Ian Hamilton Finlay outlined his plans to treat readers of his brash new journal, Poor. Old. Tired. Horse, to a free lollipop, sellotaped to the magazine’s cover. Like many of his plans from this period it came to nothing. In any case, sugar and spice weren’t really Finlay’s thing. When he started writing to Bann he was almost forty and an intermittently published short-story writer, playwright and poet. He had just published Rapel: Ten Fauve and Suprematist Poems (1963), his first foray into the new medium of concrete poetry, but most of his work as an artist lay ahead, as did the ‘avant-gardening’ of Little Sparta in the Pentland Hills near Edinburgh; for the moment he looked to be entering middle age in a state of some isolation and financial precariousness. Five years later, at the end of the period covered by this book, he had suffered a crushing series of disappointments and breakdowns, warred with almost everyone in the index bar the editor, and given up on the idea of an avant-garde collective front; but, on the bright side, he reported on 22 December 1969 that he had ‘bought a lot of new trees’ and was ‘planting 2 little groves of birches’ to frame a marble sundial.

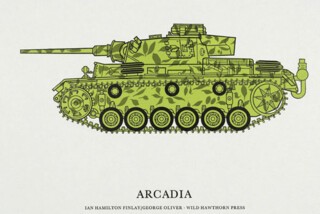

Forty-five years later, Little Sparta is thriving (open three afternoons a week throughout the summer), but its founder remains an elusive figure: the Bond villain of the modern Scottish scene. More than a garden, Little Sparta was intended as a martial state – Finlay designed stamps for it, and a flag – and with a machine gun emblazoned on its entrance it did not seem overly keen to welcome visitors. When a Strathclyde Regional Council sheriff officer came to collect Finlay’s rates arrears in 1983, disputing his argument that as a temple to a pagan god (rather than an art gallery) Little Sparta was exempt, he encountered mock French Revolutionary armed resistance. Over the years Finlay repelled not just the sheriff officer but – even after his death in 2006 – biographers too; anthologists often don’t know what to do with him either. His experiences with publishers were not always the happiest, which was one of the reasons he founded Wild Hawthorn Press in 1961, allowing him to produce and distribute his own work. Booklets, cards, posters, medals, folders and ‘proposals’ duly poured forth. They are much sought after today (a print of his poster poem Le circus!! will set you back £4000), but it took the publication of Alec Finlay’s Selections from his father’s work (2012) to bring his activities as a writer and artist into proper perspective.

Selections begins with Finlay’s not exactly forthcoming ‘autobiographical sketch’, written in 1966. He was born in 1925, ‘quite inappropriately’, in the Bahamas, where his father was engaged in bootlegging. He was soon dispatched home, conscripted during the war, and began to write short stories and plays while working as a casual labourer. ‘It was at this time that I began to suffer from nervous anxiety,’ he says with some understatement of the agoraphobia that dominated his life for decades. Never one to pass on a good pun, he was now ‘settled (touch wood)’ in the Scottish countryside, engaged on concrete poetry, and a believer in ‘intelligence, not in “thought”’. And that’s it. Finlay junior supplies essential further context: terrified cowerings under the kitchen table during the Clydebank Blitz of 1941; expulsion from Glasgow School of Art for organising a student strike; travels through Holland with the Non-Combatant Corps; working as a shepherd with a dog called Finn MacCool; and the destruction of all his paintings at the end of the 1950s. This was followed by a stay on Rousay in Orkney, an island promoted to Finlay’s paradise lost when he was forced to trade it for a psychiatric hospital on the mainland.

After returning to Edinburgh, Finlay participated in the International Writers’ Conference of 1962 and did his bit to drag the Scottish Renaissance into the Beatnik era, establishing important transatlantic connections with Robert Creeley, Jonathan Williams, Lorine Niedecker and others. The break-up of his first marriage in 1964 terminated this period of relative stability, initiating the chapter of uncertainty that coincided with his first letters to Stephen Bann. At no stage in Finlay’s career, however, were the turmoil of the artist and the peace of art necessarily incompatible. As one of his most cited bons mots puts it, a garden is not a retreat but an attack, and the green thoughts he thinks in his version of pastoral are as often as not Venus fly-traps of aggression, though none the less verdant for that. The fight isn’t entirely his alone, for all that camaraderie is hard to come by. Midway finds the British avant-garde at a promising but fraught moment in its postwar history, certainly where poetry was concerned: Bunting broke a long silence with Briggflatts in 1965 (published by Stuart Montgomery’s Fulcrum Press); Prynne’s Kitchen Poems (1968) was exciting readers in the CB2 postcode; the TLS was publishing concrete poems; and in 1971 Eric Mottram would begin his influential tenure at Poetry Review. But it wasn’t to last. ‘The present order is the disorder of the future,’ it says on the rocks of Little Sparta, though sometimes the disorder turns up earlier than expected. Within a decade Mottram had been driven from Earls Court, and a legal action brought by Finlay against Fulcrum Press had triggered a savage and self-inflicted defeat for the progressive side.

One notable antagonist, Hugh MacDiarmid, puts in an appearance early on. MacDiarmid had been Finlay’s best man, but when Finlay published Glasgow Beasts, an’ a Burd in 1961 the pioneer of synthetic Scots was scandalised by its demotic Glaswegian, and went on the attack with a pamphlet, The Ugly Birds without Wings. His ire was unquenched four years later: Finlay heard that MacDiarmid was threatening to withhold his work from the Oxford Book of Scottish Verse if its editor, Tom Scott, included anything by Finlay. To Finlay, Scott was an ‘arrogant big redhaired idiot’ and ‘foul monster’, while to MacDiarmid Poor. Old. Tired. Horse was ‘utterly vicious’ and Finlay a ‘teddyboy’. These accusations surface in a letter quoting MacDiarmid’s call at the International Writers’ Conference for the ‘immediate imprisonment of all novelists and writers who admitted to homosexuality or drug taking’, though Finlay seems to have missed the old bashi-bazouk’s description of Alexander Trocchi, at the same event, as ‘cosmopolitan scum’. Even a reference to bad weather, in the form of a ‘great gale’, triggers a parenthetical absit nomen (‘I do not mean Hugh MacDiarmid’).

Other Scottish writers were touchy subjects too: Edwin Morgan (‘Yeddie’) was a figure of suspicion, hitching a ride on the concrete bandwagon while blackening Finlay’s name as an ‘impossible’ person to the BBC and the Arts Council, though when Morgan proposed Finlay for an Arts Council grant he refused to accept it. Finlay was a careful reader of the TLS, and fumed at a ‘smart-alecky’ review of some avant-garde magazines, deciding it was written by John Willett (its real author was in fact his near-namesake Ian Hamilton, never the warmest admirer of the Scottish avant-garde). He felt too good for the Scottish papers and too isolated for the English ones, though when visitors beat a path to his door they weren’t always welcome. Nicholas Zurbrugg came for three days, leaving Finlay ‘not only exhausted but somehow furious at all such people’. Anathemas were pronounced. Harold Cohen was ‘never to be mentioned again. He is an ignorant person’, Donald Davie was a ‘wretch’, and R.B. Kitaj ‘one of the very worst painters of the century’. When words were insufficient, Finlay’s indignation broke out in truncated sound poems (‘Agh, agh, yah, boo, ach, och, yugh, pugh, poo, pshaw and dash it’). Accusations of ill-treatment from his sculptor collaborator Henry Clyne were a ‘sick, stinking, crude, lousy, wilful manifestation of second-rateness, not just of one person, but of a whole social set-up’. The poet and editor Robert Tait was a ‘fat-assed super-git and tittle-tattling toad’.

Anyone consulting Midway for pointers on the history of concrete poetry might wonder why so many people persisted in their attempts to say something meaningful about it, given the utter and unfailing wrongness of all their efforts. An anthology assembled by Jean-Louis Bory arrived in the post and ‘it is incredible … Words fail me … there are no words for the deplorable prose commentary, the dreadful printing, the filthy poems, the disgusting lies and conceit, and deceit … I really feel utterly sickened.’ A few years before, in 1963, Finlay had been insisting to Pierre Garnier that ‘“concrete” by its very limitations offers a tangible image of goodness and sanity; it is very far from the now fashionable poetry of anguish and self.’ Perhaps his gladiatorial side was designed to prove his theory by burning off all available anguish and self. Angered by a correspondent in Glasgow, Finlay announced he would send him ‘one of my famous replies’. What were these arguments really about? Though never without an eye for a chance at exposure in the English papers, Finlay reacted with allergic ferocity to the prospect of concrete poetry becoming a commercial concern, or racket. Aspiring to a condition of classical ruin, his work came with redundancy built in. Yet no sooner do we start thinking he is in the business of pastoral innocence than the swoosh of a guillotine blade terminates any simple-minded reveries. The constant flow of objurgation may have functioned as a relief from the mental pressure of it all, but if so, the reprieve was temporary. In December 1966 he hit rock bottom. He was ‘extraordinarily depressed’, unable to get up in the morning, condemned by his ‘outsider’ status to writing endless ‘hopeless letters’, leading nowhere but the hollowed-out ‘void’ in which he now finds himself.

All the evidence suggests that Finlay needed the conditions of fortified solitude he enjoyed at Little Sparta, but he also needed periodic reminders of his rightness by way of an old-fashioned stramash. The bitterest of all his battles in the 1960s was his campaign against Stuart Montgomery. Montgomery’s Fulcrum Press had published Roy Fisher, Lorine Niedecker, Robert Duncan and Lee Harwood, and seemed poised to become the publisher the British Poetry Revival of those years needed to counterbalance the waning radical commitments of the post-Eliot Faber list. Reprinting Finlay’s 1960 volume The Dancers Inherit the Party in 1969, with a few poems added, Montgomery presented it as a first edition rather than what it effectively was, a third. With anyone else an erratum slip might have sufficed, but the mistake unleashed pyroclastic torrents of indignation. When a court finally ruled in Finlay’s favour in 1974, awarding him damages, Montgomery wound down the press and pulped its stock. The fallout from the episode registered far beyond Little Sparta.

All through this period, without him saying so, Finlay was evidently becoming at least semi-famous. He chivvied Bann to use his contacts in the press, and this began to pay off with the staging of his first solo exhibition at the Axiom Gallery in London in 1968. Among the stones that litter Little Sparta is one inscribed ‘Only Connect’ (a phrase with pugilistic as well as Forsterian overtones), but something in Finlay recoiled from the thought of imposing himself on his audience. ‘I’m not sure if I really feel very keen on this idea of “involving” people in works of art,’ he wrote in March 1965. ‘It’s a wee bit like hitting them on the head and saying, There now, you are involved.’ Invitations arrived encouraging him to leave his Pentlands redoubt, but agoraphobia kept him shouting from the sidelines; in any case, the prospect of having to explain the installation in his luggage to a US customs officer was probably best avoided. One such American invitation, to participate in something called the ‘Aspen Box’ (or ‘Aspirin Box’ as Finlay called it), came from the critic and curator Mario Amaya, who had been slightly injured in Valerie Solanas’s shooting of Andy Warhol. ‘Will concrete poets ever be famous enough to be shot?’ Finlay asked.

What makes Finlay’s anger difficult for some to grasp is the classical grace and purity of the vision it served; to put it the other way round, it isn’t always clear why his revolutionary energies should have taken the form of cultivating his garden. An early poem, ‘Mansie Considers the Sea’, directs a dig at MacDiarmid but it also makes something clear about the political stand Finlay was taking:

The sea, I think, is lazy,

It just obeys the moon

– All the same I remember what Engels said:

‘Freedom is the consciousness of necessity.’

Plonking down a bit of Engels on an Orkney landscape is an act of violence, but it’s the unconscious violence of post-Romantic pastoral that Finlay can’t stand, blithely imposing its human stamp while passing off the results as a return to a state of unspoiled nature. His attempts to wriggle free of Romanticism require a whole new poetic syntax, which concrete poetry enabled, and the letters show him explaining himself, but not explaining himself, through verbal pictograms. In February 1969 he delivered some pre-Socratic wisdom on why ‘swallow equals anchor’: ‘the likeness is not wholly gratuitous since cloud also equals white ship, or sailing ship – allowing a coherent image. But, anchor equals stability and moorings, and swallow is equally an image of the swift and fleeting – as cloud is an image of the drifting, dissolving, and passing, of all things.’ Finlay is not much given to the simile. Things aren’t like other things, they just are other things. The letters don’t mention Hopkins, but Finlay’s account of the way the force of Protean transformation is released is pure instress: ‘When I say that the cloud equals the sailing ship, I mean that anchor put by cloud, is sufficient to release the idea of cloud as sailing-ship, which is surely in us.’

The faithful Bann is the most conscientious of editors, though a reference to ‘Flann O’Connor’ conjures a nightmare hybrid of Flann O’Brien and Flannery O’Connor. Almost fifty years on he can confirm doubtful dates in Finlay’s letter by cross-checking them with the date-stamp on the envelopes, all of which he appears to have kept. No explanation is offered of why only one side of the correspondence has been preserved. Holes are part of the experience of a Swiss cheese, but this doesn’t make the holes the best part, and beyond a certain point the gaps in the record become symptomatic of the fate of Finlay’s late modernism within British culture. If we see him as a second-generation recruit to the ranks of mid-century modernist loners – David Jones, Basil Bunting, W.S. Graham and R.S. Thomas – Finlay’s continued evasion of a biographer acquires honourable precedents. Jones has yet to be biographised (though long-time devotee Tom Dilworth is on the trail), Graham likewise; Justin Wintle’s Furious Interiors, a first stab at R.S. Thomas in 1996, was mostly about the poet’s Salinger-like resistance to his attentions; and Richard Burton’s recent effort on Bunting fills in the blanks by taking the poet’s work as straight biographical evidence, never the wisest course of action, much less where the author of Briggflatts is concerned.* Philip Larkin’s post-biography/Selected Letters reputational woes are the exception that proves the rule for the modern poet: pass under the biographer’s yoke or enjoy your precious hermit kingdom, but don’t expect to do both. Or if you do expect both, on your own terms, make sure to pass off your difficult side as part of your teddy bear charm. Larkin feared he’d live to see a thousand Girl Guides recite ‘This Be the Verse’ in the Albert Hall, but Finlay’s brand of poetic Jacobinism doesn’t lend itself to domestication, humorous or otherwise. Apartness and neglect are a lifelong casus belli for the letter-writer of Midway, but also the natural element of his art, inspiring and sustaining it through one crisis after another until (we realise) crisis is Finlay’s ‘normal’. In Scottish Eccentrics MacDiarmid writes of the ‘Caledonian antisyzygy’, that double helix-like interweaving of gargoyle and saint in the Scottish artistic temperament. Finlay wasn’t a gargoyle or a saint, and if he tapped artistic extremes he did so in the spirit of his old antagonist’s cri de guerre: ‘I’ll ha’e nae hauf-way hoose, but aye be whaur/Extremes meet.’

‘Beauty and Revolution: The Poetry and Art of Ian Hamilton Finlay’ is at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, from 6 December until 1 March 2015.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.