On 31 May 1578, vineyard workers on the Via Salaria in Rome found a tunnel which led them to an early Christian burial site. They had opened the catacombs: the vast network of passages cut through the volcanic tuff outside Rome in which thousands of Christians, as well as Jews and pagans, were buried. The vineyard workers were not the first to spelunk in these artificial caves. In the 1460s, avant-garde scholars in the circle of Pomponio Leto had met in the catacombs. They had formed an academy of antiquaries, and left Latin graffiti on the walls. Though they paid for their audacity when they were arrested and tortured by the suspicious Pope Paul II, they were back at it by the 1470s. Underground Rome continued to tempt explorers, especially the buried Golden House of Nero, where artists discovered ancient Roman decorative motifs, which they christened ‘grotesques’ and used to decorate Vatican loggie. Antiquaries took a serious interest in the Cloaca Maxima and other sewers.

But the Via Salaria discovery was made in a new era. Martin Luther and other Protestants had mounted a challenge to the traditions of the church. Efforts to rebut their ideas had failed, and the support of rulers who converted had enabled some of the Reformers to build new churches of their own. At the Council of Trent the leaders of the old church had regrouped. They reconfigured the papal curia, redesigned bishoprics, and devised ways to bring art and letters under expert clerical control. Still, many tasks remained. Catholic territory must be reconquered: formerly Catholic souls must be saved. Catholic leaders were determined to exploit every item of spiritual capital that the church possessed as they struggled with the Reformers for the souls of Europeans. The wall decorations of an emperor who blamed Christians for the burning of Rome were far less attractive than those of the early Christians themselves.

More important still, the catacombs were inhabited, allowing the church to enlist soldiers of a new kind in them for spiritual combat. In Heavenly Bodies, Paul Koudounaris tells their story. Thousands of skeletons lay in the newly accessible tunnels and niches. Scholars and clerics alike identified most, if not all, of them as Christian martyrs. The Catholic authorities were determined to show – in the teeth of Protestant cries of innovation and corruption – that their church had never changed. One way to dramatise the connection between contemporary Catholicism and the early church – which, all agreed, had been austere, persecuted and virtuous – was to muster these ancient martyrs and send them forth to adorn and protect Catholic churches, especially those that directly confronted Protestants. Within a decade, the church established a Sacred Congregation of Rites and Ceremonies and appointed a Custodian of the Catacombs. He in turn appointed 24 Excavators – crack cavers who specialised in seeking out the remains of the holy dead.

Along the highways, in the branching underground halls and chambers, the dead began to stir. The Excavators, and others with special permission, hunted Christian bones. Particular signs – gravestones marked ‘M’, thought to stand for ‘Martyr’; palm fronds; and vials of reddish powder, identified as dried blood – served as clues. But often no clues seem to have been needed. The seekers assembled bones into skeletons. They gave them the names of figures of renown or ancient martyrs who appeared in written sources. And they sent them out into the world, where their witness would stiffen the loyalty of Catholics and rebuke the iconoclastic frenzy of Protestants, who claimed that the use of relics was a late addition to Catholic practice and that the relics themselves were mostly obvious fakes.

The polyglot Swiss Guards made perfect middlemen. They negotiated the exchanges of financial for sacred capital that sent skeleton after skeleton, carefully identified and sealed in wooden boxes, to Catholic parishes and religious orders in Switzerland, Germany and Austria. Once the dead arrived in their new homes, their real life after death began, as Koudounaris shows with vivid, occasionally supercilious prose and splendid, eerie photographs. Officials broke the seals and took the bones out of their boxes. A coating of animal glue strengthened them and filled in gaps (fingers and toes were especially liable to suffer damage). Lost bits were modelled in wax, wood or papier-mâché and replaced. Sometimes the bones were wrapped in multiple layers of gauze.

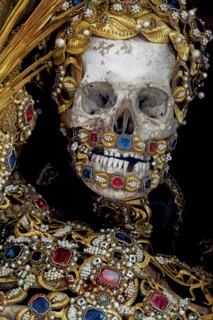

Then the real work began. The reconstructed martyrs were dressed in magnificent clothing, bedecked with beads and jewels within an inch of their deaths. Too much was not nearly enough. Then they were posed, sometimes reclining, head and upper body supported on one elbow; sometimes standing, alert, on both sides of an altar. Period outfits, including armour and swords, identified ancient members of the Church Militant, who had suffered death when they converted and refused to fight. Splendid dresses, lavishly sewn with pearls and glittering stones, adorned female martyrs. Practices of display varied. In some churches the martyrs stood or lay in full view every day. In others, their presence was signalled – and mediated – by paintings, while the bones themselves spent most of their time in cases. This was not, Koudounaris argues, because the clerics were squeamish: the paintings, after all, left little to the imagination. Rather, the martyrs were held in reserve, brought out to take part in processions on feast days. The rarity of their appearances charged the occasions with more drama and empowered the relics.

Complex rituals accompanied them on their way. One female skeleton was ‘translated’, as the technical term has it, to Munich in 1675. Greetings awaited her from other martyrs who had come before, as well as from the city of Munich itself, from Bavaria and a Christian confraternity. She was christened Munditia (cleanliness, elegance). Splendidly dressed, her bones gilt, her teeth replaced with jewels and her skull equipped with glass eyes, smiling the cheerful smile of the dead, Munditia still greets visitors to the Church of St Peter in her glass case. Since the late 17th century she has served as the patroness and protector of single, unmarried women. Her feast day, traditionally celebrated with great ceremony, falls on 17 November.

Koudounaris describes the miraculous cures that the catacomb saints performed, the festivals organised in their honour and the horror they provoked in generations of Protestant tourists. He also shows how the cult collapsed. In the 19th century most of the catacomb saints ended up hidden away in cabinets that normally remained shut or were outsourced into the private ownership of the pious. Oliver Wendell Holmes scornfully portrayed the fate of traditional Protestant theology in his poem ‘The Deacon’s Masterpiece or the Wonderful “One-Hoss Shay”: A Logical Story’. The wonderful one-hoss shay ‘was built in such a logical way’ that ‘it ran a hundred years to a day’ and then

went to pieces all at once, –

All at once, and nothing first, –

Just as bubbles do when they burst.

End of the wonderful one-hoss shay.

Logic is logic. That’s all I say.

In the same way, Koudounaris suggests that the cult of the catacomb saints collapsed naturally under its own weight. The tactics of the Excavators and Swiss Guards had always raised hackles, in Catholic as well as Protestant circles. The most surprising thing about the cult is not that it came into being but that it lasted so long.

The story of the catacombs and their upwardly mobile inhabitants is complicated: a chapter in the history of scholarship as well as the religious imagination. After 1578, native and foreign scholars – above all Alfonso Chacón, Pompeo Ugonio, the Fleming Philips van Winghe and the Maltese-born Antonio Bosio – set out to study the catacombs systematically. It was a huge and inaccessible site: there are sixty separate catacombs, though only thirty or so were known before recent times. They comprised a vast and wildly complex network of passages and chambers between seven and 19 metres deep, some of them descending as many as four storeys. Burial niches and chambers, usually small and dank, held bones and sarcophagi, while many walls exhibited a riot of religious art. Exploring this dark world required courage and ingenuity. The Milanese prelate and scholar Federico Borromeo, who visited Rome in 1586, recorded his admiration for the first intrepid explorers:

I was shown the cemeteries … There were then at Rome some young men, Frenchmen and Germans and other nationalities, who were investigating those ancient tombs, inspired by piety. Since entering them was like going into the labyrinth, they used, so to speak, the thread of Theseus, so that they could find the way out. In order that they could repeat trips whenever they wanted, they marked the places to which they wanted to return with signs.

Despite the difficulties, Borromeo explained, hurling all his metaphors into one basket, the explorers made progress: ‘Those studious young men drew and described the cemeteries, and laid out the pious paths that had previously been unknown on charts. Those terrestrial sailors could follow these, as guides, on that subterranean and shadowy ocean.’ It did not take long for Bosio, one of the principal experts, to learn that it was sensible to bring plenty of rope and candles.

Bosio died before all the plans and drawings he had collected were engraved, but Roma sotterranea – the massive book, published in 1632, which recorded his work and that of his colleagues – offered a lurid and fascinating conspectus of early Christian burial practices, art and craft. The passage from drawings to engravings imposed a considerable cost to accuracy. Roma sotterranea suggested that the catacombs really were a subterranean city, traversed by broad underground paths and punctuated by massive chapels – not the dark, spaghetti-like mass of dank tunnels and small niches that the explorers really found.

It is not hard to see why Bosio and his fellows did not accurately reproduce what they saw. As Koudounaris notes, scholars had long known that the catacombs were directly connected to the first centuries of Christianity. Saint Jerome had eloquently described the awe and fear they inspired. Prudentius had celebrated the graves of the martyrs in verse that bristled with biblical references and visual symbols drawn from the frescoed walls of the catacombs. The bones of saints led an active life, and a few centuries after Jerome and Prudentius, the known martyrs were brought up from underground into Roman churches. Tunnel tourism died away. But it was still believed that more saints remained below. In the 15th century Bartolomeo Platina, the historian of the popes, described the tunnels that flanked the Appian Way: ‘Even today we can still see the ashes and bones of the martyrs. We can still see the little shrines, where communion was offered privately, since the public edict of certain emperors forbade their being offered to God in public.’ The catacombs were no ordinary cemeteries: they were the resting place of Christians who had died for their faith. Long before the catacombs were thrown open, a framework for their interpretation had taken shape. It determined paths of inquiry and drove the way scholars read their sources.

When new evidence emerged it accordingly confirmed what was already known. Both Protestant and Catholic church historians took a special interest in the relations between Judaism and early Christianity. The Oratorian Cesare Baronio, who wrote what became the church’s official Annals, noticed a fascinating passage in the Roman historian Dio Cassius. Dio described the revolt of the Jews against the emperor Hadrian, led by Bar Kokhba in the second century:

They did not dare try conclusions with the Romans in the open field, but they occupied the advantageous positions in the country and strengthened them with mines and walls, in order that they might have places of refuge whenever they should be hard pressed, and might meet together unobserved underground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light.

Baronio himself had explored what was then called the cemetery of Priscilla on the Via Salaria several times, marvelling at its scale. ‘I don’t know what to call it,’ he wrote, ‘given its great size and many different passages, except an underground city.’ Once he read Dio, however, he leaped to a conclusion: ‘What Dio writes about the roads that the Jews created underground clearly resembles very closely the cemeteries that the Christians built at Rome as well, in sandy crypts. These were used not only for burying the bodies of the dead, but also to shelter Christians in the time of persecution.’ Seen in this new light, the catacombs were not only a lost burial ground, but a lost fortress, built in the age of the martyrs. Remarkably, radiocarbon dating of the catacombs suggests that the Christians may in fact have adopted the burial practices of Roman Jews.

The catacombs, then, were imagined as a refuge from and monument to persecution. This vision hung like a screen between the explorers and the underground world they discovered. It led them to find representations of Christian martyrdom in the art of the catacombs. One copyist saw, and drew, a martyr at the stake in what was really an Adoration of the Magi. More important, it led them to interpret the objects found among the bones of the early Christians as evidence that those buried in the catacombs had all been martyrs. Soon Bosio was leaping to the assumption that even where such evidences did not appear, they must once have been present, and restoring them by conjecture.

Martyrdom mattered, in this period – and not only to scholars. In 1555, Catholics and Lutherans negotiated a fragile settlement within the Holy Roman Empire. In France and the Low Countries, however, confrontations between Catholics and Reformed Protestants were growing sharper. Soon religious war would break out. In England, the 1530s and 1540s had seen Protestant men and women die for their faith. Under Queen Mary, more died at the stake. Meanwhile the Society of Jesus was mobilising its members to devote their lives to the Catholic version of the faith. The possibility of martyrdom faced many Jesuits, whether they carried the message of Christianity on missions to Asia and the New World or set out to preach in European states ruled or dominated by Protestants.

Martyrdom – long known chiefly from the lives of ancient saints – became a lived reality once more. Ancient martyrs were no longer merely good subjects for painters: they were up-to-date models for the Christian life. When John Bale published the interrogations of the English martyr Anne Askew in 1547, he compared her sufferings and her courage, in detail, to those of Blandina, whose heroic death was described in the ancient Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius. As John Foxe, inspired by Bale, collected materials for his Book of Martyrs, he recorded the waves of persecution with which the Roman Empire had assailed the early church, and the heroism of the early Christians going to their deaths. By the 1580s Jesuit patrons in Rome were inviting artists to adorn Santo Stefano Rotondo and other churches with images of the ancient martyrs suffering their varied deaths in living colour. Both Catholic and Protestant champions, in other words, were expected to emulate the lives they could read about on the page and see on the walls of a church.

Accounts and images of martyrdom dwelt on the details of torture and execution with a fascinated precision that can give a modern reader the creeps. A young Dutch scholar, Jetze Touber, has studied the detailed accounts by Antonio Gallonio (1556-1605) of the instruments used by the ancient Romans to inflict pain and death on Christians. These weirdly precise studies, in which Gallonio argued, for example, that the machine used to press martyrs was ‘an apparatus in which a person was flattened, instead of being squeezed like a fruit’, were made vivid by illustrations designed by Giovanni Guerra (1544-1618) and engraved by Antonio Tempesta (1555-1630). In the 19th century, they aroused the interest of readers of decadent tastes. Seen in context, however, the retrospective three-dimensional theatres of pain that writers like Foxe and Gallonio and artists like Circignani and Tempesta conjured up from the sparse records of the ancients were clearly designed not to thrill but to instruct. Theatres of pain, after all, were not fantasies in the 16th century. Every state had its macabre mise-en-scène, where confessions were extorted and dissent was crushed: missionaries from rival churches were encouraged to look on and learn the lesson. Expert executioners knew the bodies of their victims better than their nearest and dearest. They applied their tools with a matter-of-fact professionalism (and eased the way for those able to offer a gift in advance of the ceremony of pain). The calm demeanours of the martyrs impaled and racked in Gallonio’s books were the strongest possible evidence of their submissiveness and sanctity.

Martyrdom seemed – as Touber and others have shown – to be a realm in which ancient and contemporary Christianity encountered each other. To study martyrs was to erase the distance in time between the pure religion of the earliest believers and the sadder but wiser religiosity of the moderns; to see, perhaps, the possibility of living an ancient life. We do not know whether Hugh Latimer really said to his friend Nicholas Ridley, when the two were burned at Oxford in October 1555, ‘Be of good comfort, master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle, by God’s grace, in England, as I trust shall never be put out.’ Foxe claimed that he did – but only in the second, not the first, edition of his book of martyrs. What Foxe didn’t mention – as some of his modern students have noticed – was that Latimer was quoting Eusebius’s Ecclesiastical History, written in the fourth century. According to Eusebius, when the martyr Polycarp of Smyrna entered the arena where he would be examined, he heard a voice saying: ‘Be strong, Polycarp, and play the man.’ These words burned themselves into the memories of 16th-century readers. When John Jewel, bishop of Salisbury, read them in his copy of Eusebius, he transcribed them in the margin in bold Greek script. The erudite French chronologer Joseph Scaliger read them and trembled with emotion, as he confessed to readers of his greatest work on chronology, Thesaurus temporum, published in 1606. Latimer in his last accounting may well have performed a version of Eusebius’s ancient script. Many thought that he did so.

It’s in this context that we must understand the resurrection of the catacomb saints. In August 1578, an early report on the catacombs made clear how their explorers made sense of these newly accessible spaces:

The place is so venerable by reason of its antiquity, its religion and sanctity, as to excite emotion, even to tears, in all who go there and contemplate it on the spot. There, one can picture to oneself the persecutions, the sufferings and the piety of the saintly members of the primitive church, and it is obviously a further confirmation of our Catholic religion. One can see with one’s own eyes how, in the days of the pagan idolaters, those holy and pious friends of Our Lord when they were forbidden public assemblies, painted and worshipped their sacred images in these caves and subterranean places.

Entering the catacombs, like reading about martyrs, collapsed temporal distance. Visitors felt themselves transported back into that early, passionate church, whose sufferings had confirmed its members’ piety and virtue. In these circumstances, modern representations of the catacombs and their dead inhabitants inevitably recreated an imaginary world of constant persecution, met with consummate courage.

It would be wrong to underestimate the appeal of this vision. When the great French antiquary Jean Mabillon protested against the abuses of the trade in catacomb saints, he did so because he thought it terrible to mingle fake martyrs with real ones. The best scholarship and science at his disposal confirmed that many of the relics were genuine. As he knew, Gottfried Leibniz – a Protestant – had devised a scientific text which proved that the red dust found in vials with certain sets of bones was a residue of blood, as tradition claimed. It would be wrong, too, to exaggerate the ineptitude of those who mapped and recorded the catacombs and their contents. Bosio’s work included all the evidence the Protestant scholar Samuel Basnage needed to argue, convincingly, in the second volume of his History of the Church from Jesus Christ to the Present (1699) that the catacombs were merely burial grounds, not a receptacle for martyrs.

The story of the catacomb saints is typical of the larger story of historical study itself. Imagination and observation, wild speculation and precise documentation all played roles in their reawakening, as they did in contemporary efforts to identify the Jewish roots of Christianity, to work out how the emperor Constantine adopted the Christian religion or what he did for the Christian church, or to understand what Christianity had to do with the fall of Rome.

In the middle years of the 17th century Lucas Holstenius, a convert from Protestantism to Catholicism and a Vatican librarian, discovered at Monte Cassino a manuscript of the full Latin text of The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity – a vivid account of the death of a group of Christian martyrs in Carthage in 203 ce, partly cast in Perpetua’s own words. The language of The Passion was as unusual as it was striking. Its narrative sections were disjointed, and the gender-bending language of the conversations and visions the text recounted could have frightened off an editor who had no knowledge of the world it came from. Holstenius was undismayed. Inspired by living among the mighty and venerable Christian dead, he steeped himself in the language of Tertullian and other Christian writers and the mores of the Roman Empire, where Christians were done to death. He explained many points that might have puzzled readers – for example, the privileges of inmates in a Roman prison. He noted that Perpetua’s visions were recorded in a symbolic language that could also be found on the walls of the catacombs. The collective plunge of Catholic scholars into the buried labyrinths along the Appian Way and elsewhere inspired Holstenius to see that this disturbing text was genuine and to explain it in ways that we can grasp nearly four centuries later.

The early scholars were bound to make mistakes. That’s the job of scholars, especially the first ones to open up a new field. And it’s the job of later generations to adjust. The grinning, bejewelled catacomb saints who stare out from the pages of Koudounaris challenge us to engage in deeper exercises, spiritual and intellectual: to recreate lost forms of devotional life; to understand how they inspired and deformed the study of the Christian past; and to imagine what it felt like to believe that the gauze-wrapped skeleton in your church was a time lord, whose sight and touch could help to save your soul.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.