For some , Sigmar Polke is his own greatest work, which is to believe that this influential German artist, who died in 2010, counts above all because of the protean force of his personality. Polke learned the importance of persona from his charismatic teacher Joseph Beuys, and he passed it on to subsequent artists who were also wayward performers, such as the German Martin Kippenberger and the American Mike Kelley. Appropriately, the Polke retrospective currently on view at MoMA is called Alibis (it will open at Tate Modern in October and move to the Ludwig Museum in Cologne early next year).

Born in Silesia in 1941, Polke fled west with his family twice, first to Thuringia in 1945 and then to Düsseldorf in 1953, where he attended the art academy in the early 1960s. Among his fellow students was another displaced East German, Gerhard Richter, who was close to Polke at the time. Today the two are bound together art-historically in a way that recalls the pairing of Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, with Polke, like Rauschenberg, cast as the restless experimenter – the vast retrospective includes about three hundred works executed in all sorts of materials and media – and Richter, like Johns, as his restrained counterpart. After all the adulation given to Richter in recent years, there was bound to be a swing in the direction of Polke; this impressive show is that swing.

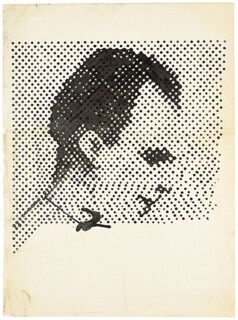

If Rauschenberg and Johns prepared the way for Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, Polke and Richter quickly adapted American Pop, which they first encountered in magazines, to German ends. In 1963, along with Konrad Lueg (who soon metamorphosed into the gallerist Konrad Fischer), Polke and Richter claimed the title ‘German Pop artists’ and, with an ironic nod to both Pop in the West and Socialist Realism in the East, contrived the label ‘Capitalist Realism’. Inspired by Warhol’s early silkscreens, Richter developed his famous blur to underscore the mediated nature of his source images. Polke meanwhile riffed on the faux Ben-Day dots devised by Lichtenstein: although they are hand painted, his ‘raster’ spots (Raster is German for ‘screen’) also indicate that his paintings derive from photographic images in newspapers and magazines. However, unlike their Pop predecessors (among whom Richard Hamilton must also be counted), Polke and Richter did not delight in mass media or commercial culture; they had fled East Germany, but were sceptical about the ‘economic miracle’ of West Germany. In two deadpan paintings from 1963-64, for example, Polke presents three support socks and three white shirts for men, crisply folded on blank grounds, in a serial manner that suggests both white-collar well-being and bureaucratic uniformity. His immaculate images of mass-produced chocolates and biscuits from the same years depict these new products of plenty as both perfect and null, and his young man in a tennis sweater is beautiful and bland in a similar way: the good life of the postwar period as the unexamined life of leisure and sport. Might the doubt raised in such paintings about a reconstructed West Germany extend to its quick embrace of American imports like Pop art? It seems so, and this makes German Pop cut critically against its artistic source as well.

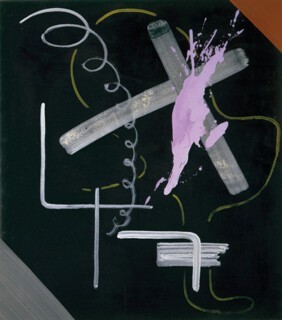

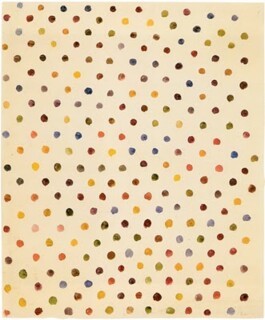

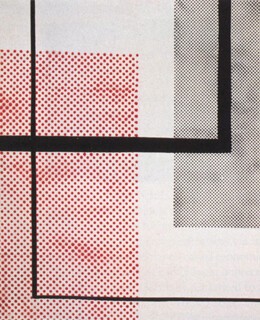

In his best works of the 1960s Polke is thus double-edged, equally biting about the vulgar lows and the arty highs of the consumer culture then new to West Germany. He was also harsh at the time about the institutional fate of modernist abstraction, though his sarcasm about it betrays a love for it too. In a watercolour from 1963, Polke reduces the pure abstraction of Mondrian, with the utopian ambition of its primary colours, to a decorative sheet of polka dots, and in a painting from 1969 he turns the transcendental abstraction of Malevich into a mock-totalitarian order from on high: Higher Beings Commanded: Paint the Upper-Right Corner Black! His best jibe is a painting simply titled Moderne Kunst (1968), an array of modernist tokens – Expressionist gestures, Suprematist geometries, Bauhausian angles – presented as so many inert signs in a one-image résumé of early 20th-century art history. These works debunk international modernism, to be sure, but they also question the West German celebration of it as a display of distance from the Nazi condemnation of modernism in particular and from the Nazi past in general – as though one could believe, as Polke once put it, in a nasty twist on the motto at Auschwitz, that ‘Kunst macht frei.’ In this respect his most acerbic piece is another painting from 1968, Constructivist, which presents, in faux-Lichtenstein dots, a faux-Mondrian composition resembling a backwards swastika. In front of an overdetermined travesty like this, which is also a well-made artwork, one hasn’t a leg to stand on.

Produced in the wake of Minimalism as well as Pop, all these paintings suggest that the abstract forms and serial formats of 20th-century art had become overcoded by the logic of the commodity image – all those advertisements for socks, shirts and chocolate bars. Nothing escapes the ‘cliché quality’ of ‘the culture of the raster’, as Polke put it in 1966, so why not push it to the limit and see what happens?

I like the impersonal, neutral and manufactured quality of these images. The raster, to me, is a system, a principle, a method, a structure. It divides, disperses, arranges and makes everything the same … [It is] the structure of our time, the structure of a social order, of a culture. Standardised, divided, fragmented, rationed, grouped, specialised.

Early on, Polke and Richter shared mundane sources such as the family snapshot, but soon Richter made banality his own, and Polke focused on the related subject of kitsch, that volatile compound of mass-produced decoration and petit-bourgeois aspiration otherwise known as bad taste. Often he used patterned fabric as the support for his paintings, on which he might screen or daub an image of a beach, a tropical palm or a heron, all tokens in the middle-class imaginary of happy relaxation, exotic travel and gemütlich decor. This anthropological expedition into the West German petite bourgeoisie is often hilarious, but it is sometimes also cruel, with a hint of snobbery about it.

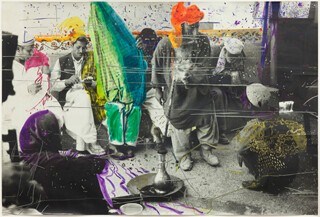

Perhaps Polke sensed the problem, for in the 1970s he ditched this cool distance. With Fluxus rather than Pop as his prompt, his work became more immersive, performative and chaotic. He drew on popular forms like comics and caricature, deployed forms of amateur and outsider art, and relied on photography and film to document his antics in the studio and beyond. At this time too, with the aid of projectors, Polke adapted from the Dadaist Francis Picabia a particular way of layered picturing, which was soon appropriated by the Americans David Salle and Julian Schnabel. At its best this hallucinatory mélange suggests not a dream space so much as a media overload, a kind of Surrealism without an unconscious in which the subject, no longer home, is dispersed among images in the world at large. At its worst it becomes a matter of rote juxtaposition to which the artist seems as indifferent as the viewer. Drugs were involved here, and that is part of the problem: although psychedelia might feel like freedom, it often looks like conventionality (as any number of rock album covers attest); sad to say, the stoned mind tends to be a factory of readymade images.

In the later 1970s Polke went south: literally, as he travelled to Pakistan, Afghanistan, Indonesia and Brazil, among other places, and figuratively, as his work became uneven. His experiments with chemicals, which extended to his paintings and photographs, issued in mixed results: at times the images point to realms of occult experience that came to preoccupy him, while at others they are simply hermetic; for the most part the process concerned him more than the product. In the 1980s his paintings tended to go big, often too big, as if the point were to keep up with the other boys in this time of Neo-Expressionist bluster. In some instances the scale is effective, as it is in a series of concentration-camp watchtowers from 1984. Yet even here opinion is divided: for some critics these paintings are chilling reminders of the Nazi past, ‘Death in Germany’ in the early 1940s to match the ‘Death in America’ of the early 1960s captured by Warhol with his electric chairs and the like; for others they begin to turn ‘Never Forget’ into its own kind of kitsch.

An acclaimed artist of the same generation as Polke recently remarked to me that Polke was ‘too creative’: there wasn’t enough concentration in his ideas or constraint in his materials to produce a logic that sustained the work over time – in short, he had too many ‘alibis’. But it might also be that his prime devices, parody and pastiche (devices that are often associated with postmodernist art of which he is an important progenitor), refuse precisely these expectations of stylistic consistency and subjective stability, and that the very point of his practice was to resist art-historical inscription and social recuperation: to show, as Benjamin Buchloh puts it in the catalogue, that any secure selfhood ‘rested on some type of oblivion or disavowal’. Yet there is a touch of the adolescent avant-garde-of-one in this position, and isn’t advanced capitalist life an effective enough auto-da-fé of the subject in its own right?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.