‘What does a woman want?’ I still remember my first encounter with the question Freud put to Marie Bonaparte in 1925, just as I recall my inability to stomach its aggressive and mystifying tone. Years have passed since then, and with them many Hannah Höch exhibitions, yet it has taken the riveting new retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery – her first ever exhibition in London (until 23 March) – to make me realise that Freud’s question was hers too. But for Höch, the ‘woman question’ was above all a social circumstance, something actively shaped by time and place. This is why, as the retrospective demonstrates, her work doesn’t answer Freud’s riddle: instead it cuts right through it, as Alexander did the Gordian knot.

Höch, granted, was an artist, not a conqueror, and her scissors required more precision than force. Or perhaps we should say that the force of her cutting was metaphorical rather than physical, as it had to be if the task was to dismantle the image of woman in Weimar culture. That image is still seductive: in it, various overlapping 20th-century powers and fictions – publicity, gender identity, desire, consumerism – are fatally fused. Yet by the time Freud was asking Bonaparte his question, Höch had been snipping and pasting the materials of mass culture long enough (since about 1918) to see its seams and weak links. And she sensed how little was needed to make those materials say – embody – something else.

As an artist, Höch was most drawn to photos of women’s faces and bodies, which she collected, cut apart and then recombined. The result is sometimes painful, occasionally frightening, sometimes both mysterious and moving; which is to say that it offers the full range of emotion that comes with the truth. To make Mischling (Half Caste) in 1924, she cut away the hair and shoulders of a bust-length portrait of a handsome dark-skinned woman; we know this because she pasted another copy of the source photo into the scrapbook she called her Album.* At this point, there was little left to do: just brush in a band of white paint and paste down a pinkly rouged mouth. Against the face’s broad planes, its movie-star curves look like the ultimate artifice, its shallowness mocked by the generous beauty of the mouth it covers and thus silences; Höch’s Mischling is a mute.

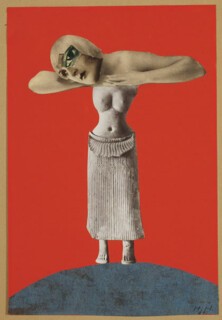

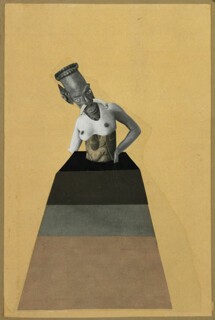

Time and again Höch puts together female faces that fracture and fray. Edges don’t meet, colours don’t match, genders are confused. What does a woman want? Can it be anything more than to take off her ill-fitting mask, which, in Höch’s images, has already started to slip? One of the strengths of the Whitechapel exhibition is that this question seems both unavoidable and appalling. What really matters to Höch is what a woman is. And what is a child or a man? These are a portraitist’s questions; but Höch is a portraitist who knows that specific identities are now glimpsed only in and through the world of prefabricated ‘types’: Melancholic, Coquette, Merry Lady, Tragic Actress, English Dancer, Our Dear Little Ones. Among the menfolk, there is even a Basque. These are personalities in production, or in performance, and their patent disjointedness leaves us wondering how one might categorise, let alone represent, the social types of today. Höch’s great and enviable talent allowed her to excavate what is artificial or tragic or ironic within images and identities, and bring it to the fore.

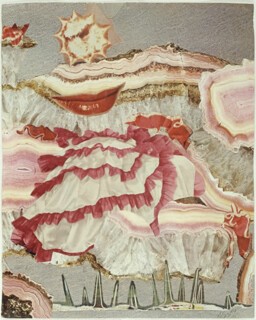

Höch also recognised just how much cultures invest in myths and ideologies of self. I can think of no more acute examination of this topic than the series of montages that she put together in 1924-30 and grouped under the title Aus einem ethnographischen Museum (From an Ethnographic Museum). To look at these constructions, each a remix of ‘primitive’ carvings and flesh-and-blood bodies, is to ask what they have in common, as Höch clearly intended we do. Everything and nothing might be my answer, except for a disjointed poetry of pathos and pain.

To look at Höch’s collages is inevitably to wonder about their maker. Does it help to know that she was the eldest of five children born to bourgeois parents in Gotha, Thuringia, or to learn that she left school at 15 because her insurance agent father and amateur painter mother decided she was needed at home? Perhaps not, until one discovers that it was only in 1912, at the age of 21, that she moved to Berlin to pursue her studies; and that she hoped to be a painter, but in deference to the family distrust of such nonsense, set out to find something useful to study, something that would give her a marketable skill. The decorative arts were the obvious possibility, and despite her lack of training, she managed to enrol in the Kunstgewerbeschule at Charlottenburg, where she studied glass design and graphic arts, and granted her family’s wish: a daughter with skills.

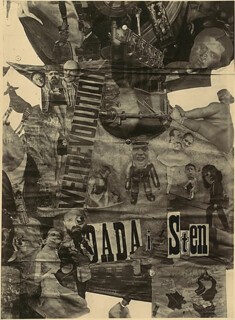

And a daughter who soon became increasingly independent. In 1916 Höch landed a highly technical job, which she held for a decade, supporting herself and her sometime lover, Raoul Hausmann. At a time when handiwork was still enormously popular among women, Höch was hired to design embroidery patterns, as well as textile and lace designs for Ullstein Verlag, the publishing house that brought out Berlin’s most popular illustrated weekly, BIZ, as well as Die Dame. Two years later, in January 1918, she sought her second abortion, and some months later bobbed her hair. In November 1918 the Council of People’s Deputies granted German women the vote. Höch joined the Novembergruppe, the revolutionary artists’ organisation sparked by the November Revolution, which had the still timely goals of promoting the reform of art schools and museums, as well as arts legislation. In 1919 she began to play an active part in Berlin Dada alongside Hausmann, George Grosz, John Heartfield and the rest. All of these artists shared her communist commitments, and all were making collage. But none demonstrated the command of mass cultural imagery Hoch developed so quickly, and none managed to work on a similarly ambitious scale. It was her show-stoppingly ambitious contribution (it measures 114 x 90 cm) to Berlin’s legendary First International Dada Fair of 1920 that spoke most clearly of a homegrown revolution, under the title Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany. It is a work that doesn’t often travel, even from Berlin to London, but the show does include a vintage photograph of a version of the composition, which Höch then revised. Entitled World Revolution (a phrase it seems to wave like a banner), it shows the crazy cacophony every good Dadaist sought: a world turned upside down, and given a hell of a shake.

In the end it seems that nothing could be more important for Höch’s art and identity than this new set of possibilities and its wider social and political context. Yet recounting them runs the risk of making them seem falsely familiar. Hannah Höch wasn’t Sally Bowles; she was a woman, even a New Woman, but also a communist and feminist, not a flapper. Soon after her arrival in Berlin from Thuringia she began to read widely, especially in philosophy and psychology; like her bisexuality (she lived for a decade with Til Brugman, a Dutch poet and translator), this too may factor into her interest in women, her concern not just with what they want, but what they are and can be. What other artist – what other woman? – could have written a manifesto for her fellow embroiderers? ‘You, craftswomen,’ she began, ‘modern women, who feel that your spirit is in your work, who are determined to lay claim to your rights (economic and moral), who believe your feet are firmly planted in reality, at least y-o-u should know that your embroidery work is a documentation of your own era!’

If there is no sure way of telling how Höch herself learned this essential lesson, her work demonstrates that she knew it through and through. She knew, too, that sometimes more than documentation is needed to ‘lay claim’ to one’s rights. Hence the scissors. Yet in the end something else is needed too: call it ‘visual intelligence’, for lack of a better term. And then think of Höch, cutting, sorting, connecting, combining, recombining, until finally a new image emerges from the wreckage and is pasted down.

Fifty years later, she was still making art. Kurt Schwitters (who became a close friend) died in 1948, Hausmann (who reinvented himself as a society photographer) in 1971, Grosz in 1959, Heartfield in 1968. Höch alone worked on. And as the show demonstrates, she understood that postwar consumerism had repackaged its promises to give them even greater allure. The collages on view in the final rooms revel in the strange new artifice of postwar printing, their chemical colours as tempting as pockets full of sweets. Trust Höch to recognise that the new images of pleasure and plenty are haunted by dangerous dreams.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.