In 1954, the sculptor Phyllis Lambert was living in Paris when her father, Samuel Bronfman, sent her pictures of the 34-storey skyscraper he planned to build on Park Avenue in New York. Bronfman, the Canadian ‘whisky king’ who owned Seagram distillers, had commissioned Pereira & Luckman to create a gleaming metal and glass edifice that resembled a decanter gift set. ‘This letter starts with one word repeated very emphatically NO NO NO NO NO,’ Lambert responded when she saw the plans. Over eight pages she dismissed the scheme as an alienating, self-consciously futuristic ‘Flash Gordon job’. She begged her father to build something instead that ‘expresses the best of the society in which you live, and at the same time your hopes for the betterment of this society’.

Bronfman, keen to have his strong-willed daughter back from Paris, where she had gone looking for a fresh start after a short-lived marriage to a Belgian banker, gave her the job of choosing an alternative. It was a privilege that would change her life and Building Seagram chronicles her valiant attempt to bring a bohemian spirit to a corporate building. With the help of Philip Johnson, MoMA’s first architecture curator, who had recently set up his own practice, Lambert spent six weeks travelling around America interviewing the most prominent practitioners of the International Style. She divided them into three categories: those who should but couldn’t (younger architects, lacking in experience: Marcel Breuer, Louis Kahn, I.M. Pei, Eero Saarinen); those who could but shouldn’t (the uninspired Harrison & Abramovitz; Skidmore, Owings & Merrill); and those who could and should (Le Corbusier, who had just finished the UN building, and Mies van der Rohe).

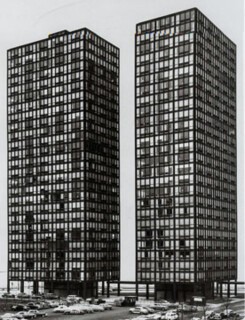

When Lambert told Mies that there were people who doubted Le Corbusier could carry off the complicated Seagram project, he replied: ‘Obviously, that’s simply nonsense. Le Corbusier is a great architect.’ His generosity impressed Lambert, who found the German émigré ‘very charming’ and ‘very interesting’. She didn’t interview Le Corbusier, whose UN building she considered an emasculation of his original plan,1 having already been ‘wowed’ by the two apartment towers Mies had built on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago, which made a brutal aesthetic of the unadorned steel from which they were constructed: ‘You might think this austere strength, this ugly beauty, is terribly severe,’ she concluded. ‘It is, and yet all the more beauty in it.’2 She noticed that many of the younger generation positioned themselves with or against Mies when articulating their styles, testament to his influence. Johnson, who had met Mies in Berlin in 1928 and curated a MoMA retrospective of his work in 1947, was Mies’s most vocal American champion and may have played a role in Lambert’s decision to give him the commission. Mies invited Johnson to collaborate with him on the building, which was twice as high as anything he had built before, giving him special responsibility for the interiors.

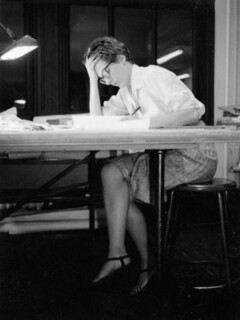

Having won her father’s approval for her selected architect, Lambert – who had no managerial or professional experience – was made director of planning, with the job of mediating between the executives and the designers. She thought of herself as in charge of quality control, the guardian against compromise, and had a glass cubicle next to the one occupied by Mies and Johnson in their temporary New York office. ‘Just her presence meant that there was no hanky-panky, nobody cut corners,’ Johnson said. ‘It wasn’t that she knew anything about buildings, but it was like having the crown prince present.’ But Lambert wasn’t the sort of person happy just to supervise. When a model needed to be built, she offered to help: the offer was rejected but she stayed late anyway to watch it being finished. When Mies drew her attention to the excellence of his chief draftsman, she sat in the man’s office for hours practising mechanical drawing after persuading him to give her lessons. ‘I took my drawing board and T-square with me when I travelled, even to Paris,’ she writes.

Lambert’s account is so engaging not only because it is the story of one of the finest skyscrapers ever made and its impact on New York, but also a kind of fairytale in which a ‘crown prince(ss)’ falls in love with architecture. Lambert, now 87, went on to study at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where Mies taught, and then became an apprentice at his Chicago firm.3 She went back to her native Canada to build in the Miesian mould and became a formidable campaigner there for the preservation of historic buildings. In 1979 she set up the Canadian Centre for Architecture, a museum and research centre that is now one of the world’s best-stocked architectural archives. In 2001 she curated an exhibition at the Whitney, Mies in America, which leaned on those collections. A recent documentary about her life, Citizen Lambert, is subtitled ‘Joan of Architecture’.

Mies was 68 when he won the Seagram commission and, considering his heavy drinking, it’s a wonder anything got built at all, certainly anything so fine, rigorous and austere. He turned up at his office at 11 o’clock each morning and, at 12.30, broke for a two-Martini lunch. ‘One more Martini and I will be doing Louis Quinze,’ he joked, making baroque gesticulations. At cocktail hour, he drank another four and, if he had a fifth, would skip dinner. He would sometimes visit Lambert’s apartment, where he would talk and listen to jazz with her friends; many of her anecdotes end with Mies, puffing on an omnipresent Havana cigar, drunkenly saluting first light. ‘Martinis or Scotch flowed until Mies would greet the dawn, the blaue Stunde, as he would say.’4

Lora Marx, Mies’s American mistress, unable to keep up, left him for a year and checked herself into Alcoholics Anonymous. The revised Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography, an expansion of Franz Schulze’s definitive 1985 study, co-authored with the architect Edward Windhorst, includes new interviews with Marx. ‘I was hungover most of the time,’ she said of their early years. ‘Mies was fascinated by the fact that I stopped as suddenly as I did, but it didn’t affect the quantity of his intake.’ Schulze and Windhorst try to put Mies’s drinking in context – the 1940s were a ‘decade awash in booze’ – but they admit that it was ‘an open question whether he was clinically alcoholic’. It seems fitting that the Seagram building, with its whisky-coloured glass windows, should be a massive monument to drink.5

Mies had dreamed of building skyscrapers since the early 1920s when, as a young architect in Berlin recently returned from the war, he’d been seduced by images of the thrusting New York skyline. Influenced by the utopian futurism of Paul Scheerbart, author of Glasarchitektur, Mies proposed a 20-storey tower completely sheathed in glass. It would have loomed over Berlin like an enormous faceted crystal: each wall was positioned at a slight angle to reflect and refract the light.6 He was fond of quoting St Augustine – ‘beauty is the radiance of truth’ – and wanted to celebrate rather than disguise structural form. ‘Only skyscrapers under construction reveal the bold constructive thoughts,’ Mies wrote, ‘and then the impression of the high-reaching steel skeletons is overpowering.’ In his glass tower, the bones of the building, with their cantilevered floor slabs, would have been visible through a shimmering, crystalline skin.

The glass skyscraper was, as Schulze and Windhorst put it, ‘beyond the threshold of constructability’ (and would only be possible in the 1970s – Mies was fifty years ahead of his time), but it was intended less as a realistic proposal than a radical, modernist statement. It would thrust him to the forefront of the European avant-garde. In the uncertainty of postwar Berlin, marked by hyperinflation, unemployment and political instability, a generation was seeking a complete break with the past; Walter Gropius had recently founded the Bauhaus school in Weimar, a laboratory that hoped to provide an architectural blueprint for a new future. Mies – who walked out on his wife and three daughters, claiming he needed ‘freedom’ – spent time in the Berlin studio of the Swiss Dadaist Hans Richter, mixing with a bohemian group: ‘This circle,’ Richter later wrote, ‘included Arp, Tzara, Hilberseimer, van Doesburg … Lissitzky, Gabo, Pevszner [sic], Kiesler, Man Ray, Soupault, Benjamin, Hausmann etc’ – an impressive roll-call.

In 1927, aged 41 and at the vanguard of modern architecture, Mies was invited to plan a showcase development in Stuttgart, the Weissenhofsiedlung, for which he invited 15 collaborators, including Gropius, Le Corbusier and Bruno Taut.7 It would become a citadel of the International Style: sixty white rectilinear dwellings with flat roofs, generous windows and balconies with ships’ railings were arranged on a series of curving terraces. A year later, Mies was invited to create the German pavilion at the Barcelona International Exposition in 1929, where he further articulated his emerging brand of minimalist perfection (favourite aphorisms included ‘less is more’ and ‘God is in the details’).8 He created a temple of modernism, elevated on a pedestal of Roman travertine, part of which held a reflecting pool lined in black glass.9 The building had a flat white roof, supported by eight slender chrome-painted columns and so appeared to float above glass curtain walls. It was expensively decorated, with partitions of green Tinian marble, etched glass and golden onyx that could be illuminated from within. They divided the floor like a De Stijl painting, and the interiors were sparsely furnished with thick black carpet, red drapes and Mies’s now ubiquitous Barcelona chairs.10 The original was demolished at the end of the fair but it was, according to Schulze and Windhorst, ‘Mies’s greatest single work. He achieved in one creative act a building altogether novel and hauntingly timeless, an inimitable statement of pure architectural abstraction.’

The following year Mies was appointed director of the Bauhaus, recommended by Gropius after the previous director, the communist Hannes Meyer, was fired under pressure from the conservative local government. Mies, who commuted from Berlin to Dessau, was not popular with the more radical students: they saw him as an architect associated with luxurious private houses (‘I am not a world improver,’ Mies responded, ‘never was, never wanted to be’), and his first action was to quash student strikes. By this time the Bauhaus had come under threat from the Nazis, who saw it as degenerate and subversive. In the hope of saving it, Mies moved the school to an old telephone factory in Berlin. But in 1933, when the Nazis suspected its printing presses were being used to produce anti-fascist propaganda, soldiers forcibly closed it down. The Gestapo told Mies he could reopen the school if certain teachers were fired and the remainder signed a loyalty oath, conditions he knew no one would accept.

Mies himself signed a public motion in support of Hitler in 1934 and joined Goebbels’s Reichskulturkammer, membership of which required a certificate proving Aryan descent. Goebbels invited him to design the Deutsches Volk, Deutsche Arbeit exhibition, which warned of the dangers of racial degeneracy, and he was shortlisted to build the new Reichsbank11 (a competition Gropius also entered) and several bridges for Hitler’s new Autobahns. It seemed, for a while, that his style of functionalism might define the new Germany. It was only when Hitler met Albert Speer, who better fulfilled his craving for monumentality, and in 1934 appointed him the party’s chief architect, that the aesthetic tide turned against Mies. Hitler, it’s said, put paid to Mies’s plans for a pavilion for the 1935 Brussels World’s Fair, despite his inclusion of German eagles, Nazi flags and a large swastika that was to be carved into the marble façade.12 The Nazis demolished Mies’s abstract brick monument to the martyred communists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht13; they also proposed knocking down his Stuttgart development to build a complex for the Army High Command. A propagandistic collage transformed the site into an Arab village, full of thawbs and camels. The Weissenhofsiedlung was saved when the HQ was moved elsewhere, though ‘Germanic’ pitched roofs were added to the white modernist buildings.

In her book, Lambert elides the issue of Mies’s attempt at collaboration; Schulze and Windhorst absolve him. Given the political realities of fascist Germany, they argue, Mies had little choice but to compromise if he was to survive; as it was, for lack of commissions, they write, he was forced to let go of his butler and maid. Nevertheless, Mies remained in Germany long after Gropius and Breuer, who had both moved to London by 1935, and, for many architectural historians, his work under Nazism infects his later buildings. Don’t his corporate monoliths, symbols of a faceless bureaucracy, represent the same cold, totalitarian aspirations as fascism?

Aware he had no future in Germany, Mies moved to America in 1938, arriving with a single suitcase to take up a position as director of the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. The city was in the heartland of the American steel industry, where more than half the world’s supply was produced. For Mies, it enabled a new architectural language. Instead of covering up the rolled steel joists with which his buildings were constructed he used the I-shaped beams in their factory-set dimensions to create plays of light and shadow, almost as if they were Grecian columns.14 Attributing a spiritual dimension to architecture, he insisted he was creating a higher, universal order that stayed true to contemporary materials. ‘I’m not working on architecture,’ Mies said, ‘I’m working on architecture as a language, and I think you have to have a grammar in order to have a language. You can use it … for normal purposes, and you speak in prose. And if you are good at that, you speak a wonderful prose. And if you are really good, you can be a poet.’

By the time Lambert met him in 1954, Mies had created a new campus for the IIT from industrial steel and brick buildings that spanned eight city blocks.15 He had also completed two apartment towers on Lake Michigan: all these buildings spoke this new language. He had also recently been embroiled in a scandal, a court case over the costs of the house he’d built for the physician Edith Farnsworth, sixty miles south-west of Chicago. It is rumoured that they had an affair, which may have coloured their spectacular falling out and the resulting court case (from which Schulze and Windhorst have discovered transcripts). The Farnsworth House, which has been compared to a Shinto shrine, is an all-glass rectangular box, raised on steel pilotis and completely open to the landscape.16 Schulze and Windhorst call it ‘the apotheosis of a worldview’: it was, they write, ‘to his American career what the Barcelona pavilion was to his European period’. Farnsworth called it ‘uninhabitable’, a one-room ‘glass cage on stilts’.

The court case was eventually decided in Mies’s favour, but Farnsworth disparaged him to the press. An article in the April 1953 issue of the popular magazine House Beautiful, ‘The Threats to the Next America’, associated Mies’s architecture with the communist menace. His buildings were ‘cold’ and ‘barren’; his furniture ‘sterile’ and ‘uncomfortable’; his aesthetic a deliberate attack on American comfort and individualism. The author took special exception to Mies’s dictum ‘less is more’: ‘We know that less is not more. It is simply less!’ Mies was upset when Frank Lloyd Wright, whom he considered a friend, echoed the sentiment: ‘These Bauhaus architects ran from political totalitarianism in Germany to what is now made by specious promotion to seem their own totalitarianism in art here in America … Why do I distrust and defy such “internationalism” as I do communism? Because both must by their nature do this very levelling in the name of civilisation.’

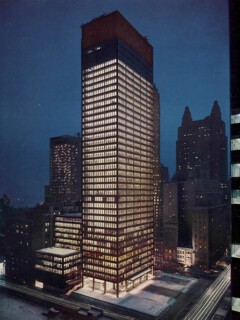

Wright had wanted the Seagram commission, but Lambert distrusted his sense of entitlement, and to her credit ignored his criticisms of Mies. She writes about the final building, a totem of capitalism, almost as if it were one of the wonders of the world. Her account captures some of the excitement one feels when one approaches the slender tower for the first time.♪ Mies gave over half of the site to a dramatic public plaza, a kind of forest clearing in the middle of the urban jungle.17 From street level, you climb up some stairs to a podium of pink granite, into which are cut step-rimmed pools, flanked by ginkgo trees and huge benches of deep green marble. As you approach, the neo-Florentine Racquet and Tennis Club opposite is reflected in a 24-foot-high screen of glass, adding to the sense of updated, refined classicism. The pink granite continues into the lobby, creating an impression of seamless progress, the elevator shafts hidden behind massive travertine panels. The svelte column, its steel trimmed in deep-brown bronze, rises over you with tremendous force: the overall effect is of discreet power.[watch]

The British architect Peter Smithson, for one, admired the elegance of the skyscraper, then the most expensive ever built: ‘Everything else now looks like a jumped-up supermart.’ The Seagram Building has since been so imitated that it’s hard to recognise its originality. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill were known as ‘the three blind Mies’ for their slavish homage, and the skylines of many cities outside New York are dotted with near replicas. ‘What makes Mies such a great influence,’ Johnson remarked, ‘is that he is so easy to copy.’ Mies himself was repetitious. By the late 1950s and through the 1960s, his firm was building all around the world, churning out architectural prose from Germany to Mexico, Canada to Brazil. In London, the developer Peter Palumbo, who bought the Farnsworth House, commissioned Mies to build a Seagram-like skyscraper at Mansion House, near St Paul’s, but in 1985 it finally fell victim to Prince Charles’s anti-modernist campaigning: ‘You have to give this much to the Luftwaffe,’ he said. ‘When it knocked down our buildings it didn’t replace them with anything more offensive than rubble.’18

There was also a backlash within the profession. In 1966, Robert Venturi inverted Mies’s famous aphorism with the phrase, ‘less is a bore.’ Mies, who died of cancer in 1969, was an easy target for the postmodernists: in 1978, Stanley Tigerman made a photomontage showing his Crown Hall Building in Chicago disappearing under the sea like the Titanic.19 A new generation of architects chose to emphasise ornament and the expressive collision of historical styles. His former disciple Johnson, whose famous Glass House was itself a Mies copy, renounced his mentor. Johnson’s 1980s AT&T tower, a few blocks from the Seagram Building, with its famous Chippendale pediment, was meant as a challenge to Mies’s stark, sterile functionalism and the corporate conformism it had engendered.20 Mies would have dismissed such reaction as ‘a kind of fashion’; he saw his architecture as beyond history. ‘Architecture,’ he used to tell students, ‘is not a cocktail.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.