Last year, I happened to meet the Norwegian writer Karl Ove Knausgaard. I had just read part of Book 1 of My Struggle, his six-volume autobiographical series, and in a scene that imprinted itself on my memory – a scene from his childhood, set on New Year’s Eve before he heads out with his friends – he steps into the family kitchen:

I got up, grabbed the orange peel, went into the kitchen, where mum was scrubbing potatoes, opened the cupboard beside her and dropped the peel in the wastebin, watched dad walk across the drive, running a hand through his hair in that characteristic way of his, after which I went upstairs to my room, closed the door behind me, put on a record and lay down on my bed again.

He and I hadn’t been speaking long when I asked him: ‘Was that a real memory – your mother scrubbing potatoes in the sink that night – or did you make it up?’

He said: ‘No no, I made it up.’

After that disappointing and confusing admission, I was unable to pick up his books for another year. To me, part of the great spell of the book had to do with how amazing it was that a writer – that anyone – could have such a photographic, such a novelistic recall of his own life, down to a detail like his mother scrubbing potatoes in the sink on New Year’s Eve twenty years ago. Knausgaard, it seemed, was a superman, his past as close to him as the present. It’s a large part of the thrill and wonder of his books: he appears to be giving an entire and precise account of his life, relationships, thoughts, feelings, what everyone says, and everything he encounters as he leaves his apartment and makes his way to the writing studio. His many readers believe that what he’s writing is the truth. But if the scrubbing of the potatoes was made up, are the books true, in the way we understand true to be? If they don’t have a faithful relationship with ‘what happened’, does it matter? Might they even in some ways be better?

Book 2 of My Struggle follows the first-person protagonist, Karl Ove Knausgaard, as he falls in love with his second wife, Linda, impregnates her three times, witnesses the birth of his first daughter, then abandons wife and baby to lock himself in a studio for several weeks where, in a state of inspiration, he writes a novel about angels, A Time to Every Purpose under Heaven. We see him accompany his children to another child’s birthday, self-hatingly pose for photographs for a newspaper, conduct a long conversation about his personality and ethics in a pub with his friend Geir, attend and throw dinner parties, and sit like a ‘feminised’ male with his daughter on his lap at a music programme for toddlers, aware that the attractive young woman with the guitar sees him as a neutered daddy, not as a man, loathing who he has become.

Scenes bracket scenes: he’ll digress for fifty pages into a memory about how he cut his face with a shard of glass in drunken agony when Linda rejected him at a writers’ conference, before returning to the digression that prompted that digression. We’ve long forgotten that what we were reading was a digression and not the central point, as if all thinking were a digression within a digression: even our lives are digressions in a larger story which we have lost sight of, imagining our own story to be the central plot, which it both is and is not. The same way there’s no stable frame around these volumes (such as a present to which he always returns, which is marked as more meaningful than points in the past) so, too, maybe life doesn’t have a stable point from which the future and past unfurl; so that the world just chaotically ‘spews out new life in a cascade of limbs and eyes, leaves and nails, hair and tails, cheeks and fur and guts, and swallows it up again’, as his books spew out cascades of digressive stories, then swallow them up again.

Knausgaard, in the first two volumes (the remaining four have yet to be published in English), is consumed with ambivalence towards fiction. At one point he imagines writing a novel about Native Americans, after discovering a painting of Indians in a canoe, but he hesitates: ‘If I created a new world’ to describe them,

it would just be literature, just fiction, and worthless. However, I could counter that Dante, for example, had written just fiction, that Cervantes had written fiction and that Melville had written just fiction. It was irrefutable that being human would not be the same if these three works had not existed. So why not write just fiction? Good arguments, but they didn’t help, just the thought of fiction, just the thought of a fabricated character in a fabricated plot made me nauseous, I reacted in a physical way. Had no idea why. But I did.

Fifty pages later, he wonders if the cascade of stories all around us in the contemporary world is to blame for the worthlessness of fiction, since ‘the nucleus of all this fiction whether true or not, was verisimilitude and the distance it held to reality was constant. In other words, it saw the same. This sameness, which was our world, was being mass-produced.’ Fiction, that’s to say, has become too fictional: it has become a genuine fiction – an imitation of fiction, not of life – and therefore too little resembles life while too much resembling life as we imagine it to be or want it to be or have been told that it is. Life as it is lived is humiliating, a banal series of errands interrupted every few years (if you’re lucky) by experiences that shoot up like a great flare – falling in love, the birth of one’s child – but (unfortunately for the novelist) it’s mostly not worth writing about.

As Knausgaard said in the Paris Review last summer, ‘it’s very shameful, writing about diapers, it’s completely without dignity.’ Perhaps in order to avoid fiction – which strives to dignify our experiences – one must avoid dignity. So it makes sense that some of the best passages in the book are about food (where is the dignity in hunger?) and childbirth (awe-inspiring but not exactly dignified), and that the most serious proclamations Knausgaard makes often conclude with a ‘what on earth do I know?’ or are conveyed in dialogue, then repudiated or mocked by another character. At the point where his personality is explained, it’s not Karl Ove who explains it but his friend Geir, while Karl Ove interrupts with questions, as curious as we are to know who he is. Here, the celebrated writer – the one who has been invested with the authority to tell us what the world is – doesn’t even know the truth about himself.

The most intense and fascinating relationship in the book is with his wife, Linda, a writer who is depicted as vulnerable, tough, tempestuous, loving, attractive, lazy, intelligent, mysterious and unstable. She apparently said to Knausgaard (in real life) that he was allowed to write about her and use her name: ‘Just don’t make me boring.’ He doesn’t. They argue endlessly, make love, struggle with childcare and household duties; he’s convinced he must be with her for ever, then is desperate to leave her, and they long for the early months of their falling in love, when for him ‘the world had suddenly opened … if someone had spoken to me then about a lack of meaning I would have laughed out loud, for I was free and the world lay at my feet, open, packed with meaning.’

The first time he meets Linda he’s married to a woman called Tonje. He spots Linda at a literary seminar and falls in love with her. If she is in a room with him, she’s the only thing he sees. When he finally professes his love, she tells him that she’s into his friend. He then goes back to his room, where he drunkenly cuts up his face. The scene is the narrative pivot of the book, a kind of death. When he wakes and realises what he’s done, and what he looks like, and that it can’t be hidden, he’s deeply ashamed, but what can he do? It’s the last day of the conference and he has to say goodbye to everybody. When Linda see him, she cries. He returns to Tonje, determined to forget about Linda, and does.

Several years later, he leaves Tonje (temporarily? permanently? He’s not sure – it’s a sudden decision) and moves from Arendal in Norway to Stockholm, where he knows one person, Geir, who has published a book on boxing which was great but not successful. Knausgaard answers an advertisement in the paper for a flat and just as he’s about to sign the lease he notices on the front buzzer that Linda lives in that very building. He realises he can’t take the flat. She would think he’s stalking her. He finds a place somewhere else but is shaken by the coincidence. Later, he calls her, but their first few encounters are without spark: they have nothing to say; she is not the woman he remembered.

Soon, his feelings for her heat up, and they go on a double date to the theatre to see an Ibsen play directed by Bergman. That night, after the show, he realises two things:

The first was that I wanted to see her again as soon as possible. The second was that was where I had to go, to what I had seen that evening. Nothing else was good enough, nothing else did it. That was where I had to go, to the essence, to the inner core of human existence. If it took forty years, so be it, it took forty years. But I would never lose sight of it, never forget it, that was there I was going. There, there, there.

That his realisation of what his art is to be about comes in the same breath as his certainty about what his life is to be about – Linda – must mean they have something to do with each other, are important for each other. To go towards her – with everything this will come to mean about letting those most daunting and naked emotions that accompany true love rise to the surface, along with the endless repetition of duty that accompanies bringing up children – means also going to those places in art. Emotional vulnerability and domestic routine must be ‘the essence, the inner core of human existence’. And so, on the one hand:

I hated fighting and scenes. And for a long time I had managed to avoid them in my adult life. There hadn’t been any brawls in any of the relationships I’d had, any disagreements had proceeded according to my method, which was irony, sarcasm, unfriendliness, sulking and silence. It was only when Linda came into my life that this changed … I was afraid when she went after me. Afraid in the way I was afraid when I was a boy. Oh, I was not proud of this, but so what? It wasn’t something I could control by thought or will, it was something quite different that was released in me, anchored deeper, down in what was perhaps the very foundation of my personality … When I defended myself my voice would break because I was on the verge of tears, but to her that could have easily been caused by my anger, for all I knew. No, now that I came to think about it, somewhere inside her she must have known. But perhaps not the precise extent of how awful the experience was for me.

On the other:

So we took the elevator down to the food section in the basement, bought Italian sausage, tomatoes, onion, leaf parsley and two packets of rigatoni pasta, ice cream and frozen blackberries, took the elevator up to the floor where the Systembolaget was and bought a litre carton of white wine for the tomato sauce, a carton of red wine and a small bottle of brandy.

In A Time to Every Purpose under Heaven, the novel that preceded the My Struggle series, Knausgaard animates the eccentric 16th-century (fictional) polymath Antinous Bellori, as well as Cain and Abel, and Noah and his family. He describes the biblical characters’ inner lives and family dynamics, which (in the case of the Noah story) play out against the backdrop of a steadily rising sea that Noah’s family tries to escape. Knausgaard says in A Man in Love that when he was writing the character of Noah’s sister Anna, he had in mind Linda’s devoted mother, Ingrid, whom we meet several times in My Struggle. Anna is ‘a woman who was stronger than all of them, a woman who, when the flood came, took the whole family up the mountain, and, when the water reached them, took them higher until they could go no further and all hope was lost’.

The lives of these biblical characters were easily worthy of Knausgaard’s attention – could there have been any question? They were already literature. Those Indians in the canoe were worthy of being made literature: they had been beautifully painted already. But if Knausgaard put Ingrid’s personality into Anna, how to make the less justifiable leap to writing Ingrid as Ingrid, naming her and placing her in scenarios he’d witnessed, not just read about?

To write about the people one knows but to call them Noah or Cain is to dignify them – to say our stories are really that big. But to get beyond dignity involves removing that frame, which lends so much importance to what we do. So that while we might feel some anger towards a man who betrays his family to do God’s work by getting into an ark and sailing past his people who cry desperately for his help as the waves rise to drown them, it’s not quite the same as what we might feel towards a man who actually, not just in myth, held the phone away from his ear as his wife cried and demanded that he return to her and their baby, after he deserted them for the quiet ark of his writing studio, so he could carry out whatever writing is in an age in which no one believes it’s God’s work.

In Book 1, Knausgaard says that although he had been trying to write about his father for years it had not worked ‘because the subject was too close to my life, thus not so easy to force into another form.’ With literature, ‘everything has to submit to form … Strong themes and styles have to be broken down before literature can come into being. It is this breaking down that is called “writing”. Writing is more about destroying than creating … Freedom is like destruction plus movement.’ When Knausgaard found the new form that would allow him the freedom to write about his father, he felt he could write basically anything. My Struggle and A Time for Everything were composed in a heat: something in him was unlocked. What allowed the destruction to take place? He began A Time for Everything weeks after the birth of his first child and right after his return from Tromoya, where he did a reading and, for the first time as an adult, visited the place where he grew up. As he rides in a car with Geir,

all the places I carried inside me, which I had visualised so many, many times in my life, passed outside the windows, completely auraless, totally neutral – the way they were, in fact. A few crags, a small bay, a decrepit floating pier, a narrow shoreline, some old houses behind, flatland that fell away to the water. That was all … There was nothing. But lives were still being lived in these houses, and they were still everything for the people inside. People were born, people died, they made love and argued, ate and shat, drank and partied, read and slept … Small and ugly, but all there was.

Knausgaard has said that while he forgets painful stories told to him in confidence by the people he loves, and plots of novels he’s read, he vividly remembers landscapes and rooms. Writing, for him, involves filling these rooms. But before that could happen in the way it did here, he had to encounter the rooms and landscape of his childhood and past as auraless, ‘small and ugly’. Nostalgia is a false distance, we feel it everywhere, its ‘sameness’. The aura of nostalgia is akin to the aura of ‘the novel’. It brings life close but makes that life unreal. It turns the past into something it was not, the way conventional novels make of life something it is not. When nostalgia dies, our romantic stories about our lives die, our impressions of who our parents were die, and novelistic conventions also die. Also dead is the consensual safety that fiction brings with it, the presumably ethical veil behind which writers protect themselves from their family and friends: it’s not you, that’s not your name, your hair is not red, it’s made up.

People have condemned Knausgaard for writing about intimates and acquaintances so transparently, but that doesn’t mean he doesn’t care about being ethical. Artists never really know the scope of what they are doing as they work; it is only afterwards, when the world tells them, that they see. ‘All I wanted was to be a decent person,’ he writes. ‘A good, honest, upright person who could look people in the eye and whom everyone knew they could trust. But such was not the case. I was a deserter, and I had done terrible things.’ Knausgaard told the Guardian that when the manuscript was finished Linda ‘read it, on a long train journey to Stockholm. She called once to say it was OK. Then she called again and said our life together could never be romantic ever again; this was all so frank. Then she called a third time, and cried.’ If he had turned their life into a novel, it would have been romantic, rather than ‘so frank’. She might have blushed, not cried.

In A Time to Every Purpose under Heaven, Antinous Bellori is writing a treatise about the way the nature of angels changed over the centuries. Why were they once glowing and glorious and involved with mankind but were now dim and depressed and kept themselves apart? At the book’s climax, we see that they were hurt in a way that can’t be undone: Antinous realises that when God entered the body of Jesus, he ceased to exist anywhere other than in that body, so that when Jesus was crucified and died, God too died and was dead. And he has remained dead ever since.

It’s a powerful scene, and I can’t help but see the My Struggle books as taking place on a stage where not only is God dead (what else is new?) but on which we can so carelessly kill him. And it’s repeated again and again. Knausgaard says to Geir about God: ‘“Before, he wasn’t here, he was above us. Now we’ve internalised him. Incorporated him.” We ate in silence for a few minutes. “Well?” Geir said. “How has your day been?”’

There is a correspondence between the passive dullness of the angels that made Antinous despair and the ‘completely auraless, totally neutral’ landscape that disheartened Knausgaard: a relationship between the death of God and the death of the Flaubertian way of writing novels. Both had to respond to a crisis of ubiquity with a new form, a new distance. Knausgaard implies that God was once in the situation of fiction today: God was ‘wherever you turned’ and therefore ‘invalidated’. To remain real, both art and God had to become ‘a life, a face, a gaze you could meet … the gaze of another person … Not directed above us, nor beneath us, but at the same height as our own gaze.’ And as if to emphasise how painful and risky (even unto death) such a gaze might be, at the point in the book where Knausgaard meets his own face in a mirror, he takes a razor and mutilates it in humiliation and shame.

Most novels carry a whiff of pride, the novelist just over there in the curtains, beaming at what he’s created. But life is not a gold medal, so such a novel is not like life, it’s like a badge the writer hopes to wear through life. The distance between life and Knausgaard’s book is not ‘constant’ with those sorts of fictions. Its gaze is consistently ‘at the same height as our own gaze’. The realism is really real.

Of course Knausgaard couldn’t have remembered his mother washing potatoes in the sink, although he would have known in general that she did – the potatoes have to be washed. How could I have been so disappointed? What does that disappointment mean? Only that I’d imagined the novelist was dead in this case, and he wasn’t. We continue to invent, because the past eludes us all; it’s past, it’s gone, even for Knausgaard.

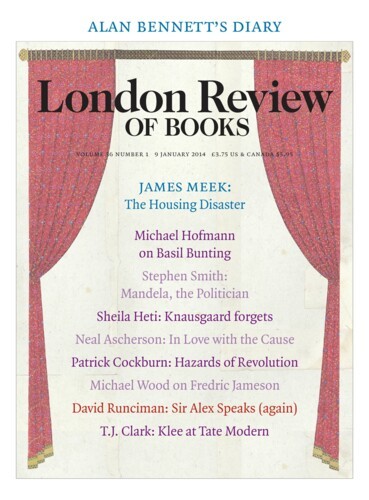

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.