When Tracey Thorn was 17, she bought an electric guitar through a small ad in Melody Maker. Only when she got it home did she realise something was missing: she needed an amp. She played the guitar anyway and got ‘into the habit of making very little noise’. A couple of years later, with Ben Watt, she formed the band Everything But the Girl. In the last thirty years they’ve been ‘signed, dropped, re-signed, mixed and remixed’ while selling around nine million records.

Thorn grew up in the suburbs twenty miles north of London. She describes herself as a shy but confident child: ‘I felt central, liked for who I was. Special.’ There was no need to raise her voice. When punk was at its height she was, like most of us, listening to Nilsson and Brotherhood of Man. Halfway through 1977, aged almost 15, she changed from being someone ‘who had barely noticed pop music … into someone who cared about very little else’. From this point on, her diary filled up with music while retaining its hormonal underlay: ‘J.J. Burnel is so hunky!! Luv his jeans!!*???!!**’ In September she bought drainpipes, ‘dead punky!!!’ In October she had her first spiky haircut and realised it was impossible ‘to carry on being civil to your parents while claiming to like the Stranglers’.

The Sex Pistols album Never Mind the Bollocks was released around the time Thorn was having that haircut. I remember glimpsing it in a shop window from the school bus. The word ‘bollocks’ had been covered with brown paper but the real thrill lay in the acid yellow and neon pink of the sleeve. This was a time when it seemed as if the entire country was wrapped in brown paper. The reverberations of punk travelled slowly, like everything else in England at the time. Even after it reached us, we hesitated. I remember feeling an intense connection with whatever this was but it took some time to convince myself that it might want to connect with me. Just as we got round to ripping our jackets and piercing our noses, Sid Vicious died of an overdose and the Sex Pistols split up. Thorn’s diary declares, ‘This is the end of punk, really,’ which she now thinks was ‘probably just something I copied out of the NME’. Realising she was only 13 when a lot of the singles she treasures were released, she wonders whether she bought them later.

By 1979, punk bands had settled down to touring old cinemas and dancehalls. We’d fetch up at the local Odeon or Palais in leather and plastic, pink hair and chains. We’d hand our tickets to ageing usherettes and take our red-plush seats. Afterwards we’d shuffle outside to wait for someone’s dad to pick us up. Sometimes we’d find the place surrounded by police in riot gear. Even they were bored and so when something came along that looked like trouble, it was made to be so. Those of us of Thorn’s generation didn’t document our musical lives beyond some ticket stubs and the odd snap. Lacking the frame by frame archive of social media or the cameraphone makes it easy to confuse a collective memory with your own. You can start out with a confident ‘I was there’ and find yourself quickly reduced to ‘was I?’ Thorn has her diaries but squares up to herself all the same: ‘I’d always kidded myself that it was punk that got me started.’

I still think it was. By pretending not to be ‘musical’, punk made music possible. Mainstream pop was too opaque to emulate, disco too exotic and prog rock assumed a level of professionalism that was the stuff of grown-ups. We wanted bands that sounded nothing like pop and looked nothing like pop stars, produced by labels we’d never heard of. We could be all that ourselves. If you were 14 in 1976 you were young enough, as Thorn points out, to be impressed by punk and old enough to respond to its DIY ethos. No one talked about PR or managers; they set up fanzines and made cassettes. There was a lot of talk of democracy and little conception of this as a career. Resources were shared as if it was assumed that a band would make its own records and put on its own gigs. Thorn’s local fanzine offered advice: ‘If you are planning a gig in St Albans, write to the Director of Leisure and Legal Services.’

What was emerging into the space punk cleared was its opposite: ambitious, allusive, varied, and serious to the point of being ponderous. A political stance was assumed. Bands like Orange Juice wrote crafted pop, and others such as A Certain Ratio gave us something we could dance to. There were connoisseurs of synthesisers, drum machines and digital delay, like the Human League or Martin Hannett, the Phil Spector of British post-punk who produced Joy Division and Section 25. A new quietness was pioneered by the Young Marble Giants: spare melodies, withheld vocals and the barest murmur of guitar. We also realised that, for all its insistence on the obliterating new, punk had a past. Girls grew their hair and wore their grandmothers’ dresses while boys donned suits. We listened to jazz. Thorn wanted to join a band to develop a more certain version of herself, to have something to belong to, and maybe to find a boyfriend. So she bought her guitar, practised and waited. Sure enough she was asked to join a band called Stern Bops and was soon dating the lead singer. They got an avuncular write-up in the St Albans Review: ‘They do a nice line in pop originals, that combine echoes of the 60s beat-group sound with a modern up-tempo zest.’ Thorn still has a Stern Bops rehearsal tape with ‘DO NOT PLAY EVER’ written on one side and ‘Some good stuff’ on the other. She seems always to have known whether or not something was working. When she was first asked to sing, she agreed to have a go if they let her try it inside a wardrobe. She had to explore it first on her own. She seems to have been more interested in the music she was making alone in her room: ‘I just want to be on my own and get on with playing, without anyone noticing.’ Perhaps this first band was a way of establishing her musical self while concealing it at the same time.

Her next step was to form her own band, the Marine Girls, in the summer of 1980 with some friends from school. Within weeks they’d made a tape on a borrowed four-track recorder and funded fifty copies through Saturday jobs in a village toy shop and a space-themed burger bar. They placed an ad in the NME. The blank confidence of youth and their roll-your-sleeves-up attitude was rewarded when letters arrived from a distribution company, a Germany radio DJ and a Dutch fanzine. They had yet to play outside Tracey’s room.

The Marine Girls sound like what they were – a bunch of girls playing songs in a bedroom while trying not to disturb the parents downstairs. Thorn is amazed that these fragile sketches have become so respected but recognises their substance. Their friable nature is a form of resistance. They sound suspicious of the very idea of performance and are determined not to charm. They’re trying to find a way to be a band without being boys. Thorn makes it clear that being in a band didn’t make you one of the boys, or one of the girls either. ‘Local boys in other bands would flirt with us a bit, then run away. And for girlfriends, they’d often choose girls who weren’t in bands, and would never be in bands, but just wanted boys in bands to be their boyfriends.’ If you were the only girl hanging out in the record shop you soon learned that music was something boys wanted to show you, not have you show them.

James Hunter has written in the Village Voice that Thorn’s voice ‘remains moored and intact, full of … radical mid-range rationality’. Her way of writing about her feelings is similar, almost diagrammatic: when she was in the Marine Girls, a broken heart ‘inspired me to write a few good songs, and maybe even brought about a shift in my songwriting that marked the true beginning of everything I’ve done since’. There was a boy and it was difficult and it hurt for a long time. A bandmate asks her how the songs ‘On My Mind’ and ‘Don’t Come Back’ can be about the same person. Thorn tells us and she doesn’t.

The Marine Girls signed to the independent label Cherry Red. I was also in a band signed to Cherry Red and remember the strangeness of arriving in a white stuccoed part of London where people had offices. I don’t think I’d been in an office before. The label was run by two men I thought of as a splenetic genie and a groovy dad. It was like being sent to see the headmaster only for him not to know why you were there. The groovy dad now reminisces online about how it was all about making money from the publishing; the genie was last seen fronting a campaign to save the architecture of Milton Keynes. Thorn signed a contract so draconian that when she and Watt extricated themselves, Everything But the Girl’s first album sat on a shelf for a year before being released.

We couldn’t carry music about with us but had to listen to it in our rooms and the music we made was bedsit scale. It worked if taken only as far as a slightly bigger room. My band’s first gig was at the Beet Bop Club in Camden and was, in the incidental manner of the times, reviewed in Sounds. No one expected us to put on any sort of show. The building looked as if it had been condemned and we had to use the lavatories in the pub next door. In this context, the spare and wobbly thing we were doing worked. People weren’t expecting it to be good, only interesting. Such music easily got lost when it came to making a record. In our case, it was like entering an acoustic hall of mirrors as the producer tried to bounce and double what we did into palatial pop. We weren’t good enough to survive this or determined enough to resist it, and that was that. Cherry Red never got the however many songs per year their contract demanded, not that they wanted them.

Being in a band, even one with a record deal, ‘wasn’t a job’ and didn’t stop Thorn from going off to Hull University in 1981, where she met Ben Watt. Like her, he was signed to Cherry Red. They ‘clutched at the little we had in common in our music, realising immediately how much we had in common in our attitudes’, and there followed a period in which they ‘wrote songs and made records’ and it really did seem as simple as that. Thorn was leading three musical lives with the Marine Girls, with Ben Watt and as a solo artist, and studying too. In 1983 the Marine Girls split up. Everything But the Girl had already found their beginning.

Everything But the Girl’s first single, a cover of ‘Night and Day’, was a hit. Journalists trekked to Hull, where the duo let the meter for the gas fire run out (‘Anyone got 10p?’) and gave bolshy interviews about not being part of the new jazz movement. They encouraged the story that they’d turned down Top of the Pops because they had exams – when they hadn’t actually been asked to perform. Their delayed first album, Eden, was a commercial success but received a confusing critical response. Thorn is at her best describing the years of becoming ‘a bit famous’. She draws our attention to what was least real about each rock’n’roll moment. When Everything But the Girl get a gold disc, she points out that it’s just any old record sprayed gold. You can tell by looking at the number and length of the tracks.

Early on they became aware of the ‘apparent gap between the actual sound of the music we made and our intentions in making it’. They were discovering what they weren’t but not what they were, a question they never really solved. What sounds like a problem became their driving tension. Its origin was in part Thorn wanting, and not wanting, to make noise. Her first solo album, A Distant Shore, was recorded in a makeshift studio in a garden shed. It’s quiet and unpolished but claims attention. The guitar’s a bit knackered and the backing vocals come in as if someone has opened a window. Its trapped riffs and tiny melodic gestures come up against the sureness of Thorn’s voice and the strength of her songwriting. She was 19 and already resisting herself.

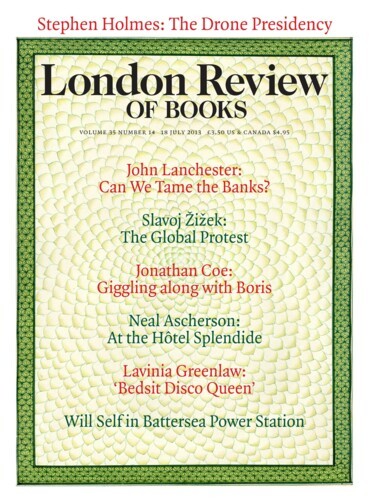

In Bedsit Disco Queen, Thorn approaches herself from a friendly distance. She has said she wrote the book to remind herself why she became a musician but her instinct is to protect that impulse rather than interrogate it. She will not dwell on why music came to her so easily, where her songs come from or how they’re recorded but she’s upfront about what it’s like to worry about reviews only to discover there aren’t going to be any. She’s proud of the highs and unabashed by the lows.

This makes it sound as if she’s gone back and put everything in proportion when what we get is a subtle account of a career that has depended on unsettlement. She has often felt out of place and not quite of the times. Her greatest hits have been cover versions, remixes or early work that she’s surprised to discover has gathered a fanatical following. She’s good on the delicate matter of being the next big thing, the same old thing and then the new old thing. She’s acutely aware of the status of her peers: ‘Watched Aztec Camera on Wogan – Roddy is number 41 this week … Morrissey went straight in at number 6.’ It’s as if she feels they all know how to do something she doesn’t. Focusing on her own uncertainty, she makes light of what it must have taken to preserve such a sense of self.

As their status settled at the level of ‘semi-VIP’, as she glimpsed on a restaurant booking, Thorn set about ‘projects or diversions’. She and Watt bought a house in the country, planted things, looked out the window and came back to London. She did an MA. By 1990, they were ‘having to go abroad to feel loved’. She took up gardening and thought about doing a PhD. In 1992, Watt became ill with an autoimmune disease that nearly killed him. She’s said relatively little about him but his absence still seems abrupt. At this point Thorn tells us what their relationship means to her. He was in hospital for nine weeks, much of the time unconscious: ‘Little bleeps and alarms would suddenly go off and I’d jump out of my skin, until a nurse would come by and flick at a drip line with her fingernail.’

The trauma must have made pop stardom seem somewhat trivial and from this point on Thorn and Watt stopped worrying about it. Instead of feeling insecure they unsecured themselves. Thorn worked with folk heroes Fairport Convention and trip-hop pioneers Massive Attack. They were dropped by their label just as a remix of their single ‘Missing’ was about to become their greatest hit. Thorn observes herself observing all this and concludes that her heart was no longer in it. She withdrew just as Watt started to develop a new career as a DJ and producer. They had three children and after some years at home she restarted her solo career and, like Watt, has flourished in the new indie scene while enjoying a cult following as another generation, to whom the word ‘bedsit’ means nothing, discover post-punk.

Three years ago Thorn said in an interview that she’d written a memoir but that it wouldn’t be published: ‘It’s not a book … It’s just like this happened and then this happened.’ Bedsit Disco Queen ends in 2007 and she hasn’t brought it up to date. She put it away in a box and then came across it while moving house. It makes sense that she was only going to be able to write the book by thinking it wasn’t really a book and she wasn’t really going to make any noise.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.