The pop star Justin Bieber was born in London, Ontario, the son of two teenagers. His mother was a high-school dropout who liked beer and LSD, and his father an amateur musician. Jeremy Jack Bieber, also a heavy drinker, was in the local jail the night his son was born. He abandoned the family when Bieber was ten months old and went on to pursue a career as a martial arts fighter, often missing visits to his son, resurfacing now and then with a guitar in tow as the boy got older. Justin Bieber grew up very poor and very Christian with his mother, Pattie Mallette. She’s now 38, believes in family values (she is the executive producer of a new anti-abortion film), and recently admitted on American television to being celibate since the mid-1990s. She’s waiting for marriage. She had already found God one night before she got pregnant (and sober). The faith came to her in a kind of Blakeian vision that was ‘very intense and very real’, as she writes in her bestselling memoir, Nowhere but Up: The Story of Justin Bieber’s Mom: ‘With my eyes closed, I saw in my mind an image of my heart opening up. As it unfolded, gold dust was poured into the opening and filled every inch of my heart until there was no room left for even one more speck to squeeze through. Somehow deep in my spirit I knew the gold dust represented God’s love.’ Mallette describes her pregnancy as a miracle comparable to the Immaculate Conception. She was on the pill, took it ‘religiously’: ‘There was no way I was part of that 2 per cent group of women who experience a “margin of error”,’ she writes. ‘I wasn’t pregnant. I couldn’t be. It was impossible.’

‘Anything is possible,’ Justin Bieber writes in Just Getting Started, his second ‘100 per cent official’ memoir, published last year. Friends and family encouraged Mallette to abort the child, but she gave birth to her only son on 1 March 1994 and raised him mostly herself. Bieber could play the drums by the time he was five – his mother’s church friends helped buy his first kit – and he picked up some piano too. His first love, though (he is Canadian) was hockey. He kept his musical talents to himself. To the rest of the world, he was normal.

Bieber became a star in 2007, when his remarkable vocal range was discovered by a former Atlanta club promoter called Scott ‘Scooter’ Braun, the 31-year-old son of a dentist and an orthodontist from Greenwich, Connecticut, while he was browsing YouTube. Braun saw footage of Bieber performing at a local talent show in a dim auditorium, dressed in an awkwardly fitting Oxford shirt, singing a cover of ‘So Sick’, a 2006 ballad by the pop star Ne-Yo:

Gotta change my answering machine

Now that I’m alone

’Cuz right now it says that we

Can’t come to the phone

And I know it makes no sense

’Cuz you walked out the door

But it’s the only way I hear your voice anymore.

It’s unlikely that Bieber, then 12, was old enough to have his own private phone line, but the appeal of his velvety pre-teen tenor was not lost on Braun, who began sending emails to Bieber’s school and calling his mother at home. Braun had managed a few rap groups that never took off and his career was stuck. But early on, he was as obsessed with Bieber as millions of teenagers are today.

Braun would later refer to himself as ‘a camp counsellor for pop stars’, making explicit the creepiness of a grown man travelling across a continent in search of a cherubic 12-year-old boy. Braun became Bieber’s manager, as well as the de facto father and protector the boy never had. The singer’s entourage likes to play up these familial analogues. In Never Say Never, a heavy-handed concert documentary about Bieber playing to a sold-out crowd at Madison Square Garden at the age of 16, the Bieber camp explains what they do and where they fit in the professional family the singer – or, really, his mother – has constructed. Ryan Good, stylist, is ‘like the coolest older brother ever’; Carin Morris, wardrobe, is ‘like Justin’s big sister’ (she was also Braun’s long-term girlfriend, which makes the metaphor a bit yucky); Scrappy, stage manager, ‘kinda’ looks at Justin ‘like a little brother’; Kenny Hamilton, security, says sternly that ‘it’s an uncle-nephew relationship.’ Braun reiterates that ‘it’s a family’ and they’re all ‘making sure the kid’s OK’. The patriarch steps in from time to time like any decent overbearing parent. When Believe, Bieber’s third studio album, didn’t receive any nominations at this year’s Grammy Awards, Braun tweeted: ‘This time there wont be any wise words, no excuses, I just plain DISAGREE. The kid deserved it. Grammy board u blew it on this one.’

Perhaps the snub had something to do with lyrics such as: ‘Chillin’ by the fire while we eatin’ fondue/I dunno about me but I know about you.’ The couplet comes from ‘Boyfriend’, the album’s first single; its video was viewed eight million times in 24 hours on the music website VEVO. It doesn’t matter that Bieber’s songs don’t hold much appeal for anyone who isn’t between the ages of six and 16 and female. The mania surrounding his celebrity extends to adults, as when Bieber, at the age of 17, was forced to take a paternity test after highly publicised allegations that he had fathered a child with a 20-year-old fan. The term ‘viral’ has rarely seemed so appropriate a way to characterise a public figure’s appeal. He’s capable of causing mass hysteria with a single message to his 35 million Twitter followers (who call themselves – why wouldn’t they? – ‘Beliebers’). In 2011, he lost 80,000 of them in a protest at his having had a haircut. He single-handedly launched the career of another of Braun’s clients, Carly Rae Jepsen, singer of the hit ‘Call Me Maybe’, simply by tweeting that it was ‘possibly the catchiest song I’ve ever heard lol’. A 12-second video of Bieber vomiting onstage in Arizona has been viewed over 19 million times. ‘Milk was a bad choice! lol,’ he tweeted after the show, to almost 70,000 retweets.

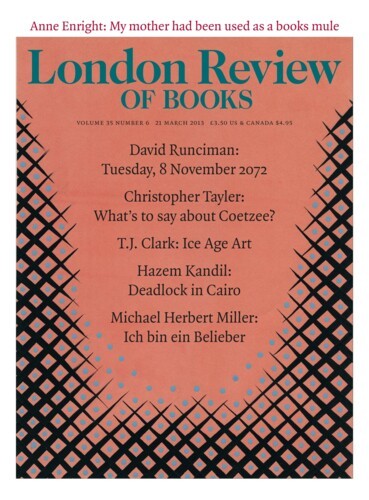

It was only a matter of time before somebody wrote a novel about him. Teddy Wayne’s The Love Song of Jonny Valentine follows an 11-year-old Bieberlike entertainer on the last leg of his tour in support of his second album.* The novel’s epigraph is something Bieber told a reporter from Interview magazine in 2010: ‘I want my world to be fun. No parents, no rules, no nothing. Like, no one can stop me. No one can stop me.’ Jonny Valentine is six stone, give or take, but he commands stadiums. Afterwards, he plays video games. He thinks he should want, as Bieber claims in his first memoir, First Step 2 Forever, to be ‘a regular kid. I don’t expect, nor do I want, anyone to treat me differently.’ Bieber also writes about how much he likes playing to thousands of people a night. An adolescent pop star’s life is a balance between the Pinocchioesque wish to be a real boy and the need for more fame. It’s hard to say where the fun is in any of that, and Wayne’s book is about this irony. Wayne also makes a relentless attempt to imagine a private life for his hero poised on the edge of puberty, packing in numerous details that are mercifully left out of Bieber’s memoirs. ‘Some guys ended up hurting a girl’s feelings or making her mad, because they were working too hard to look cool,’ Bieber writes in First Step 2 Forever. ‘Not me.’ He leaves it at that.

Wayne has written a fiery, sometimes funny, only slightly overwrought critique of the exploitation of children at the hands of the rapacious music industry, but he may have lost sight of the real tragedy of Bieber. More than any other pop star before him, Bieber gives the impression of an alarm system sounding a series of warnings for a doomed adulthood. His hypothetical backstage suffering is less interesting than the impossible maintenance of a pristine public persona that lets in mistakes every so often, only to call attention to the façade. Bieber is by now the most self-conscious celebrity in the world, partly because of the extensive record of his life, refreshed every few minutes on Twitter, YouTube, blogs, mainstream media and the rest of the internet to which he’s owed his fame from the start.

Wayne takes a slapstick approach to over-abundant fame, with Jonny forced to go on engineered dates set up by his label as a photo op and being told that he needs to slim down because he’s looking a bit chubby around the waist. Because Wayne uses the first-person, the novel really does resemble Bieber’s own ghost-written memoirs, in both cases a middle-aged man’s conception of the way a child talks. But there’s a melancholy to Bieber, despite the sappy music and the studied innocence. There’s a sense that for his entire childhood he’s merely been childlike, acting the part but robbed of the real thing.

And now he’s in the process of relaunching his career as he rapidly grows into adulthood. Pop stars come with expiry dates. In search of career longevity they constantly have to shape-shift with evolving musical tastes, and revamp themselves for fans who are growing older themselves. On the night of the Grammy Awards, Bieber announced he would do an hour-long live video interview on the website Ustream. At 8 p.m., the time the awards ceremony was to begin, an oddly tough-looking Bieber sat shirtless in front of a video camera, his chest muscular and tattooed, ready to take his fans’ questions. Ustream crashed almost immediately. It’s hard to say how his ratings would have compared to the Grammys’ (39 million people tuned in, just four million more than Bieber’s Twitter followers). As consolation, Bieber released a new song that night called ‘You Want Me’. Most of the lyrics are still embarrassingly naive, but he sounds older. His voice is huskier. The sentiment is more overtly sexual, too.

He just turned 19, the age his father was when he impregnated his mother. After a circus-themed birthday party at a club in London was ruined when his underage guests were turned away, Bieber sent out a tweet that read ‘Worst birthday’. The news was picked up by the Guardian, the Huffington Post and American television networks, among other outlets; the grown men and women who work for these organisations all expressed shock that a teenager had got stroppy. The incident turned into a global campaign to help Bieber feel better, with the singer himself chiming in every now and then to tell his Twitter followers that ‘it ain’t always easy but is what it is. Gonna stay focused.’ His fans replied with Operation Make Bieber Smile: they inundated him with Twitter messages along the lines of ‘I love you so much, never stop smiling OK?’ Braun joined the discussion: ‘Life is a roller coaster. Just know when u dip low it is only to build excitement as u will fly high again. Enjoy the journey.’ It’s too late for him to be a regular kid who turns up on time and poses meekly for the camera.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.