In 1974 Ian Berry won a bursary from the Arts Council to photograph ‘the English’. He’d already made his name in South Africa as the only photographer to record the Sharpeville massacre in 1960. Two years later Cartier-Bresson invited him to join Magnum. He went on to work in Vietnam, Israel/Palestine, Northern Ireland and Ethiopia; he was in Czechoslovakia in 1968. When the BBC asked if they could accompany him to Whitby on one leg of his journey for the Arts Council project, he was uneasy. He didn’t fancy being trailed by a toff in jeans and a bunch of technicians, but quickly established a rapport with the film cameraman. In the one-eyed professions every Cyclops finds a soulmate sooner or later.

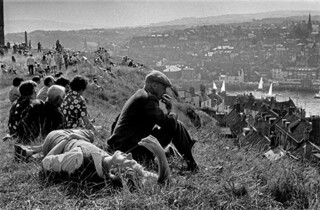

Berry’s The English is one of the most impressive full-size prints in Magnum Contact Sheets, a vast, exquisite elegy to the old way of taking photos ‘just as the shift to digital photography threatens to render the contact sheet obsolete’, as the blurb explains.* ‘Threatens’ is an understatement. You know it the minute you set eyes on Berry’s gelatin silver print of the men and women of Whitby relaxing on a Sunday in summer above the River Esk in 1974. It is an iconic image of the English at leisure: the two oblivious protagonists – an older man in a tweed cap, a younger reclining with a straw in his mouth – hold the foreground. To their left, a group of seven people, two of them women with floral print dresses; around and below them, the town; beneath the clutter of chimneys and dormers rising from pantiled roofs, four white sails seem to hang above the water.

Berry admits that ‘the man in the tweed cap first drew me to this scene’ at a time when tweed caps ‘were already becoming unfashionable’. His remark gets to the heart of a book in which the sense of vanishing worlds is painfully insistent, both in terms of the photographic subject and the manner of its production. So much of what photography has to say about appearance, it turns out, is really about disappearance: cultures and places changed beyond recognition, lives long gone, and the old arts of the analogue camera and the darkroom with them. Both subject and practice take on a lyrical, heritage quality as they’re superseded or extinguished. In his piece about the end of the Kodachrome colour slide (LRB, 3 February 2011) Julian Stallabrass pointed out that nine of the images produced by the American photographer Steve McCurry – another Magnum member – when he petitioned to shoot the last roll of Kodachrome in 2010 were of a vanishing nomadic tribe in Rajasthan. The commemorative style of Magnum Contact Sheets is less rhetorical. The procession of photos is anything but stately: over and over they assert that the moment when the light struck the surface of the film is the only one that matters. It’s like hearing a succession of short passages, each proposing a climax, from a sublime piece of music that has yet to be written or performed.

First desk for the violinists is Cartier-Bresson, a Magnum founder. He is also the one to explain, in mitigation, that the unrivalled shot which seems to make history and confect it at the same time – George Rodger’s photos of Coventry during the Blitz, Eve Arnold’s portrait of Malcolm X, any of Gilles Peress’s famous photos of Bloody Sunday, Peter Marlow’s unforgettable portrait of Thatcher at the Tory Conference in 1981 – is the result of a long deliberation over at least 36 exposures. The organisation of the book goes on to make this clear, interleaving prints and contact sheets, with chinagraph marks around the lucky miniatures that went on to become giants in the public record.

Cartier-Bresson likens the contact sheet to ‘a psychoanalyst’s casebook’, and then to a text, and then to the preparation of a meal (photography itself can never mix metaphors): ‘A contact sheet is full of erasures, full of detritus. A photo exhibition or a book is an invitation to a meal, and it is not customary to make guests poke their noses in the pots and pans, still less into the buckets of peelings.’ A contact sheet is intimate and reliable even so, like a reporter’s notebook, evidence that can be invoked if the winning shot is called into question. As Kristen Lubben writes in the introduction, it places an image ‘back within the flow of time from which it was removed’.

I learned to sell photographs before I even had a rough idea how to take them, in Eritrea, Angola, Western Sahara. I used to trawl around as a print journalist with a second-hand Nikon body and two lenses, 35 and 50 mm, hoping to top up the pot. Now and then an editor would pick up the chinagraph and ring a frame on a contact sheet and I’d collect the fee. Once in Angola my Nikon camera body, with the 35 mm lens attached, took a delirious tumble across the cabin floor of a Boeing 727, during a tyre-burst landing. Body and lens were smoked like haddock but the exposures came out OK. I shot a last roll of film in the same camera, with the same lens, about seven years ago. I’m not sure how my new Canon digital SLR would cope with a bump of that kind. But I’m a fan of digital photography. It’s easy and beautiful. It goes nine-tenths of the way to meet you. There’s nothing you need to know that hasn’t already been thought of. It’s a Sherpa in the lowlands of photography, lugging crampons and oxygen tanks through the wet grass, allowing proud owners like me to convince themselves they’re really making a great ascent. Up on the summit the Magnum photographers survey the world through more discerning eyes.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.