By my count, though I may have missed a few, this is the 25th volume of Ezra Pound’s highly distinctive correspondence to see the light of day. The first selection of his letters, edited by D.D. Paige and culled from the years 1907-41, was published in 1950, when Pound was four years into what would be a 12-year sojourn in St Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, to which he’d been confined indefinitely after pleading insanity at his trial for treason in 1946. Paige’s selection introduced to the world madcap Ez the compulsive letter-writer, all hectoring capitals and italics and doolally spelling, here berating recalcitrant magazine editors, there puffing his chosen (in the main, pretty well chosen) band of modernistas; here, somewhat less happily, solving the world’s political and economic woes by promoting Social Credit, there championing the achievements of his great hero, Benito Mussolini. Coming the year after the scandal caused by the decision to award the Bollingen Prize to The Pisan Cantos, the book’s publication caused something of a furore – as indeed did all things Poundian in the immediate postwar era.

A small batch of his letters to Louis Untermeyer was published a few years after Pound’s release from St Elizabeths in 1958, and then, in 1967, his extensive and fascinating correspondence with James Joyce. But it wasn’t until the 1980s and 1990s that the archive floodgates really opened. These decades saw the appearance of volumes individually devoted to Pound’s letters not only to fellow writers such as Wyndham Lewis, E.E. Cummings, Ford Madox Ford, Louis Zukofsky and William Carlos Williams, but also to various editors and patrons: to the somewhat mysterious Margaret Cravens, a Paris-based piano student from Madison, Indiana, who in 1910 bestowed on Pound an annual stipend so he could concentrate on his poetry, only to commit suicide two years later; to John Quinn, a lawyer and collector to whom T.S. Eliot gave the manuscript of The Waste Land; to James Laughlin, founder and editor of New Directions (or Nude Erections as Pound liked to call it); to Alice Corbin Henderson of Poetry; to Scofield Thayer and James Sibley Watson of the Dial; to Margaret Anderson of the Little Review. Two hefty books collected his courtship letters to Dorothy Shakespear, and those written to her some thirty years later from the Disciplinary Training Centre outside Pisa, where he was incarcerated after surrendering to US forces in May 1945 – an act prompted by his fear of being summarily executed by victorious partisans. And anyone yearning for yet more of his cracker-barrel views on political and economic matters could read his spirited attempts to convert Senator Bronson Cutting, Congressman George Tinkham and Senator William E. Borah to Poundian solutions to American policy issues: these were collected in volumes published in 1995, 1996 and 2001 respectively.

His epistolary career began with this of 1895 to his mother, Isabel, who was visiting relatives in New York. Pound was nearly ten:

Dear Ma,

I went to a ball game on saturday, between our school and Heacocks, the score was thirty-five to thirty-seven our favor, it was a hard fight in which wee were victorise.

They put on a colorerd man for first base and then to pitcher but he soon was knoct out as he gave two ma[n]y men baces on balls, as it didn’t do any good they chucked him off, the umpire cheated untill pa came and then he quit.

This cheating umpire, who, in the telling, was forced to quit by the arrival of Pound’s pa, is the first of many representatives in Pound’s writings of institutional malfeasance requiring the intervention of the heroic, dissenting individual. If the mild-mannered Homer Loomis Pound, who worked nearly all his life in the same fairly humble job in the assayer’s department at the US Mint in Philadelphia, beginning on a salary of $5 a day that rose, in nearly thirty years’ service, to only $2500 a year, really did somehow challenge and defeat the crooked umpire (whom the young Pound goes on to suggest might have been bribed), this was very much the exception rather than the rule.

Pound’s casually bullying letters to his father suggest that in the main Homer was more than happy to accept the role of awestruck progenitor and enabler of genius, whatever the cost: and there aren’t many letters home from the early part of Pound’s career that don’t contain a request for funds or an acknowledgment of money received. ‘Being family to a wild poet aint no bed of roses but you stand the strain just fine,’ Pound compliments him in a 1909 letter, sent from London. The benign, ungrudging Homer seems to have complaisantly endured being chivvied in letter after letter to look after his impatient son’s literary interests in America by liaising with editors or drumming up subscriptions for magazines to which Pound contributed, or by using what contacts he had to procure favourable reviews for his US publications. Homer, it is clear, by no means provided a paternal template for the aggressive individualism that came to mark Pound’s increasingly vituperative attacks on targets ranging from literary London to F.D. Roosevelt (or ‘Franklin D. Frankfurter Jewsfeld’ as he took to calling him), from the Victorian anthologist Palgrave to the ‘kikefied usurers’ – to borrow a phrase from one of his wartime radio broadcasts – he came to blame for both world wars.

This book contains 849 letters or postcards, not all of them of surpassing interest. This is from 9 January 1908, from Crawfordsville, Indiana, where Pound had recently begun work as an instructor in romance languages at Wabash College:

Dear Mother –

I don’t know that there is anything especial.

Two lectures out of the way. I can’t send ’em to Dad ’cause they’re only notes & my improvisations & reading out of books.

Things run smoothely. that is about all there is to be reported.

Love to you and Dad

EP

The book’s editors, Mary de Rachewiltz (Pound’s daughter by the American violinist Olga Rudge), and Joanna and David Moody (who is at work on a multi-volume biography of Pound) have chosen to include every message from the poet to his parents in its entirety, however mundane. I suppose one might pause to note from the above the extent to which Pound was open to sharing with his father his work in progress, even if it was only university lectures; and indeed Pound’s literary successes – and those of his friends and acolytes – dominate most of these bulletins back to Mr and Mrs Pound from their only offspring. Occasionally the editors vouchsafe a glimpse of Homer’s tentative but enthusiastic responses to the increasingly rebarbative poetry his genius son sent back from his European travels to suburban Philadelphia. On receipt of a first draft of what would end up as Canto II, the one that begins ‘Hang it all, Robert Browning’, Homer records that reading it made him feel ‘like one going up in an Airship – The Mechanician has honoured me with a seat – and we are soon up in the pure azure – Time and space are nothing.’ He modestly declares his opinion of little value, but reports himself ‘glad that in that little room – in London a son of mine can lose himself in such matters’. However, he rather timidly ventures:

may I be permitted to suggest that as this poem is not for the Yahoos – for after the first word it soars way above the crowd – so use a different word than ‘hang’. It seems to me ‘Listen-all’ – would be a better word.

After this hesitant stab at removing his son’s mild expletive, Homer confesses, rather plangently, that there are ‘many words and names that I do not understand as you well know – but nevertheless it gives one a desire to see the places – I wish, some day we can go over them together –.’

How revealing are these letters of the processes whereby a not particularly gifted language student from a middle-ranking American university became one of the major catalysts of international modernism, and the author of the most polyglot poetry the world has yet produced? They certainly flesh out the indignities of his university career, particularly after he transferred from the University of Pennsylvania to Hamilton College, in Clinton, New York, where he was refused entry to a fraternity house and had to spend most of his time alone. Yet a decade or so on, and Pound had become the vibrant centre of an artistic circle that changed the course of poetry and fiction as decisively as any in literary history.

‘You just go on your nerve,’ Frank O’Hara declared of the business of writing poetry, and Pound developed a nerve like no other. What is so weird and unique about his poetry, however, is not just the nerve it exhibits, whether it takes the form of mistranslated Propertius or chopped up bits of John Adams or baffling Chinese ideograms, but its bewildering dependence on other literary sources to get going. A tiny early poem, ‘On His Own Face in a Glass’, from Pound’s first collection, A Lume Spento (1908), gestures somewhat melodramatically towards his lack of a secure sense of selfhood, filling a whole line with ‘I’, spaces and question marks:

I ? I ? I ?

The poem that precedes it in A Lume Spento, ‘Masks’, suggests the only solution Pound would ever find to this extreme sense of hollowness or absence, a sense which was projected back onto his native land in his frequent denunciations of America as a cultural desert. In ‘Masks’ he celebrates the way ‘tales of old disguisings’ can become ‘Strange myths of souls that found themselves among/Unwonted folk that spake an hostile tongue’. By ‘tales of old disguisings’ he seems to mean the literary tradition that would furnish him with all his various masks or personae or hero figures, from the swashbuckling Occitan troubadour Bertran de Born to the Renaissance man of action Sigismondo Malatesta, from the Anglo-Saxon Seafarer to the Bowmen of Shu, from the wise, unwobbling Confucius to the ever resourceful Odysseus. Although obsessed with the importance of defining and promulgating a poetic canon that would in due course inspire an American Risorgimento, Pound seems to have experienced his own poetic selfhood as radically disjointed and centreless. And this resulted in an oeuvre that has no centre, ‘a tangle of works unfinished’, as he put it in a late canto; his ‘errors and wrecks’ lay all about him and he could not ‘make it cohere’. Notes for an even later canto return to the dilemma staged by ‘On His Own Face in a Glass’ and ‘Masks’:

That I lost my centre

fighting the world.

The dreams clash

and are shattered –

Some sixty years on, and the terms in which he construes the drama between the absent self and the dreams or ‘tales of old disguisings’ have hardly changed. The melodrama, of course, remains too, and is present in nearly all of Pound’s most resonant moments: ‘As a lone ant from a broken ant-hill/ from the wreckage of Europe, ego scriptor’; ‘Old Ez folded his blankets/Neither Eos nor Hesperus has suffered wrong at my hands.’

The hints of vulnerability dramatised in ‘On His Own Face in a Glass’ and the late cantos and fragments are rare in Pound. Even at his unhappiest, writing home from the ‘wilderness’ of Hamilton College, an element of bravado keeps interrupting his attempts to convey his loneliness:

Absolute isolation from all ‘humanity’ does not tend to increase punctiliousness.

Don’t be alarmed, there are a few white folks even up here.

Nice disagreeable sort of letter isn’t it? Glad you & dad seem to be enjoying life.

I don’t suppose anyone can live in books steadily & not get grouched occasionaly. Have seen & heard nothing out-side this cramped narrow lopsided hole except last Saturday.

I’m not grumbling only it gets monotonous.

His early poems abound in figures who translate this fear of monotony and isolation into a high romantic rhetoric of bravado derived largely from Browning. ‘Bah!’ exclaims Cino, based on the troubadour Cino da Pistoia, a friend of Dante’s, in another poem from A Lume Spento: ‘I have sung women in three cities,/But it is all the same;/ And I will sing of the sun.’ Vagabonds and rovers, blood-red spearsmen, red-cloaked ladies in towers high, woodlands dim … Pound’s early effusions failed to strike a chord with the more savvy and sophisticated Eliot when they were pressed on him by the Harvard Advocate editor W.G. Tinckom-Fernandez in 1909: ‘It seemed to me rather fancy, old-fashioned, romantic stuff, cloak-and-dagger kind of stuff,’ he recalled a half-century later. ‘I wasn’t very impressed by it.’

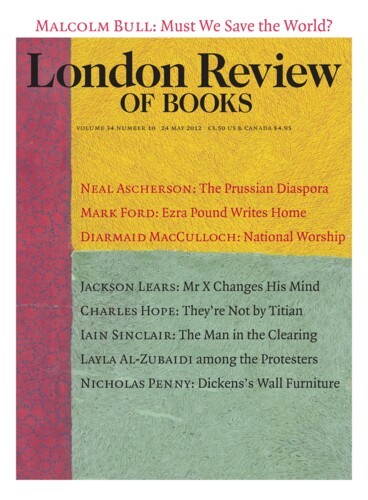

Pound first visited Europe in 1898 with his mother and her sister, Aunt Frank, when he was 12. He was eager to relate to his father that during a trip to Kenilworth Castle ‘the guid kept our party, after the others had left and showed us the dining room, where no visitors are allowed.’ Pound’s delight in penetrating into regions beyond the official itinerary, so striking in his own research habits in later life, seems already in evidence here. The family made a second grand tour, on which Homer was included, in 1902, and this volume reprints a hilarious photo from the party’s visit to the Alhambra, with Homer, Isabel and the 16-year-old Ra, as he was then still called, sporting elaborate Moorish costumes. As if in anticipation of Eliot’s comment, the young Pound is kitted out with a flowing robe and sword, and cradles an enormously long antique flintlock rifle.

Looking back on these early visits to Europe, he decided – this is from a letter of 1912 to Aunt Frank – that they had saved him a great deal of ‘work’, by which he seems to have meant that they enabled him to absorb European culture intuitively. ‘Really,’ he observed in a letter of 1916 to Iris Barry, ‘one DON’T need to know a language. One NEEDS, damn well needs, to know the few hundred words in the few really good poems that any language has in it.’ Unlike the more rigorously scholarly Eliot, who in ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’ declared that proper knowledge of a tradition could only be obtained by ‘great labour’, Pound was, it’s fair to say, always something of a bluffer. Late in life he even said he’d never really read much, though I doubt the various annotators who have devoted their lives to tracking down his allusions would second this.

How different 20th-century poetry would have been had these two bookish Americans opted for the university careers with which both flirted in their early twenties. ‘Found a new good poet named Eliot,’ Pound proclaims to Homer in a letter from London of 22 September 1914, and he immediately set about arranging for ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ to appear in the Chicago-based Poetry magazine, for which he acted as ‘foreign correspondent’ and general browbeater of its founding editor, Harriet Monroe. Like so many young London literati of the period – Wyndham Lewis and T.E. Hulme and Richard Aldington and F.S. Flint – Eliot fell under the spell of Pound’s beguiling mixture of flamboyance, generosity and startling self-confidence. Together they orchestrated what in hindsight can seem like a hostile takeover of the somewhat moribund London poetry scene. In return for his promotion and support of Eliot, which reached its climax in his magisterial editing of The Waste Land – for which he also arranged the awarding of the Dial’s annual $2000 prize – Pound suggested the younger poet might explain to the world the crucial nature of his own poetic innovations. Ezra Pound: His Metric and Poetry was published by Knopf (heavily subsidised by John Quinn) as a pamphlet in 1917, and was the first sustained critical assessment of his work. It was, however, issued anonymously, for as Pound observed in a letter to Quinn, it might otherwise seem rather too naked a bit of mutual back-scratching: ‘I want to boom Eliot, and one cant have too obvious a ping-pong match at that sort of thing.’

Pound also played a major role in dissuading Eliot from returning to Harvard and the academic life probably awaiting him: he urged him instead to marry Vivienne Haigh-Wood, despite her skittishness and troubling nerves, and stay in London to write poetry. Il miglior fabbro’s own renunciation of academia had occurred seven years previously, in 1908, in the course of his second semester at Wabash, and also involved an English woman, one usually described as a female impersonator (it seems she specialised in doing monocled toffs, an act for which, alas, there proved little demand in Crawfordsville). On Pound’s own account, he ran into her on a street corner one freezing night, and, taking pity, invited her back to his lodgings to get warm. She slept in his bed, he slept on the floor, but this offence against decency, when brought to the attention of the Wabash College authorities, was enough to get him summoned by the president. ‘Dear Dad,’ he wrote,

Have had a bust up. but come out with enough to take me to Europe. Home Saturday or Sunday. Don’t let mother get excited.

Ez.

I guess something that one does not see. but something very big & white back of the destinies. has the turning & the leading of things & this thing. & I breath again.

As an afterthought he added: ‘In fact you need say nothing to mother till I come.’ (Throughout these letters Pound is far more confiding to his father than his mother, to whom he is often somewhat testy, complaining for instance, of her ‘general objection to my way of doing nearly everything’.) On official investigation of the matter Pound was exonerated, but by then he’d decided he’d had enough of university life in a small mid-Western town. ‘Dear Dad,’ he wrote a few days later, ‘Have been recalled but think I should rather go to ze sunny Italia.’ He was paid the balance of that month’s salary, $200, and felt able to depart as undisputed victor in the dispute: ‘Have had more fun out of the fracasso than there is in a dog fight & hope I have taught ’em how to run a college.’

By late April he was installed in Venice, ‘by the soap-smooth stone posts where San Vio/meets with il Canal Grande’ (Canto LXXVI). From there he writes back to his ‘Benign & Reverend Parent’, in answer to an inquiry into the state of his finances: ‘I am by no means sure it would not be pleasanter to starve the body in Venice than to starve the soul in a backwoods hamlet.’ Anyway, thanks to remittances from home and his redundancy cheque, he was able to pay a Venetian printer to produce 150 copies of A Lume Spento, one of which he dispatched to W.B. Yeats. Yeats courteously replied that he found the book ‘charming’. A more public acclamation of his talent came from the popular ‘poetess’ – as the review’s headline describes her – Ella Wheeler Wilcox, a family friend, who exclaimed in the American Journal Examiner: ‘Success to you, young singer in Venice! Success to “With Tapers Quenched”.’ An even more enthusiastic review appeared in the Evening Standard & St James’s Gazette, shortly after the young singer had moved to London: ‘Wild and haunting stuff, absolutely poetic, original, imaginative, passionate and spiritual … words are no good in describing it.’ The author of this encomium, described as ‘a Venetian critic’, was almost certainly Pound himself.

Like Whitman before him, with whom he made a posthumous ‘pact’ in the 1913 poem of that name, arguing that they shared ‘one sap and one root’ which meant there should be ‘commerce between us’, Pound devoted enormous amounts of time and energy to the business of self-promotion. Of course Whitman pinned his colours wholly to the mast of American democracy, while Pound committed himself to what, on the face of it, looked like an antithetical programme: the wholesale denunciation of American culture, which he dismissed, in a poem addressed to another American exception, Whistler, as the work of a ‘mass of dolts’. Eliot took firm steps in his introduction to Pound’s Selected Poems of 1928 to separate his maverick modernist confrère, to whom he still felt deeply grateful for the caesarian Pound had performed on The Waste Land, from the embarrassment of an association with Whitman, ignoring Pound’s acknowledgment in ‘A Pact’ of his ‘pigheaded father’: ‘I am … certain,’ Eliot observed, in his best pulpit manner, ‘it is indeed obvious – that Pound owes nothing to Whitman.’ Yet the tradition of the American huckster lurks somewhere in the hinterland of both, and these letters show Pound matching Whitman in acts of self-boosterism, badgering his father to prod and harry US editors and reviewers, and offering in return an artlessly boastful account of his conquests in literary London: Laurence Binyon, Henry Newbolt, Maurice Hewlett, Victor Plarr, Selwyn Image, Ford Madox Ford … and finally, after months of networking and glimpses from afar, Yeats himself! In a letter of 30 April 1909, he records spending five hours with him the previous day and announces a change of plan: ‘I shall not go to Venice. the London game seems to have too many chances in it to risk missing them by absence.’ Of those Pound targeted only one significant player eluded him, as he recalled in Canto LXXXII, written in Pisa: ‘Swinburne my only miss.’

But unlike Eliot and Henry James (finally tracked down and secured in March 1912), Pound never sought to be absorbed into British society, though he proudly told his mother, in the letter recounting his meeting with James, that he was now established enough to ‘revolve’ in the ‘strata’ of London society described in James’s novels. It is to her that he recounts such triumphs as a ‘few days with Lady Low’ in Dorset, for, proud of her pedigree as a Wadsworth, and a distant connection to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Isabel harboured hopes that her gifted son might restore some of the ancestral respectability squandered by her wastrel father, whose itinerant career included a spell peddling patent medicines and toothache pellets. If only Ezra could get appointed to a post in the American embassy in London! But it was the life of a bohemian that her errant son adopted, one subsidised first by his parents, then by Margaret Cravens, and then by his wife Dorothy’s annuity of £150 a year. Not that, like his maternal grandfather, Harding Weston, he didn’t occasionally dream up get-rich-quick schemes, such as his proposal to William Carlos Williams that they open a syphilis clinic together on the north coast of Africa: Pound’s expansive ‘social proclivities’ would secure a clientele of ‘wealthy old nabobs’ for Dr Williams to treat, and they’d be able to ‘clean up a million … and retire to our literary enjoyments within, at most, a year’.

In the poem to Whistler, first published in 1912, Pound attempted to characterise the dilemma facing the genuine American artist:

You had your searches, your uncertainties,

And this is good to know – for us, I mean,

Who bear the brunt of our America

And try to wrench her impulse into art.

Pound never conceived his self-education in Europe as an escape from what was involved in being a ‘murkn’, to use his own orthography, but as the best way of bearing the ‘brunt’ of what he considered his nation’s inadequate culture, so as to ‘wrench’ it towards a significant national art. His poems are directed towards those whom, in another poem on this theme, ‘The Rest’, he addresses as the ‘helpless few in my country,/O remnant enslaved!’ To this elect but thwarted tribe, in thrall to the ‘mass of dolts’ in the so-called land of the free, Pound’s aesthetic feats in Europe will serve as both paradigm and encouragement:

You of the finer sense,

Broken against false knowledge,

You who can know at first hand,

Hated, shut in, mistrusted:Take thought:

I have weathered the storm,

I have beaten out my exile.

The strenuous, adversarial nature of this process meant that, like Thoreau in Walden, or Whitman in Democratic Vistas, or James in The American Scene, Pound could be seen as contributing to that most venerable of American genres, the jeremiad. But in leading him to embrace the antithesis of American democracy, Italian fascism, it would eventually put him decisively beyond the pale of even the generously capacious and forgiving traditions of American dissent. What’s more, it led him to seek out scapegoats for the political and artistic frustrations he suffered, and from 1916 onwards attacks on ‘chews’ begin sporadically to disfigure his writings, including these letters. While he seems to have met little firm resistance from his parents in this slide towards extremism, a letter of Homer’s reprinted here, in response to one of Pound’s that has been lost, records his being asked at some function, ‘Why does Ezra hate the Jews?’ and having to reply that he didn’t know. ‘Why,’ he continues, ‘if it was not for them (the jews) here in Phila – this old town would be a desert. They are the ballast in this old ship.’ Ezra begged to differ, and while there is nothing in these missives to match the rabid rantings of his wartime radio broadcasts, in one of which he commended Hitler for ‘having seen the Jew puke in the German democracy’, while in another he advocated, instead of ‘an old style killing of small Jews’ a more targeted ‘pogrom up at the top’ of ‘the sixty Kikes who started this war’, they still on occasion make for queasy reading. One gets the sense that his parents, for the most part, opted to sidestep these issues when his letters raised them, deeming such fulminations part and parcel of being a wild poet.

On Homer’s retirement from the Mint in 1928, the Depression looming, they decided to join the son of whom they’d seen so little over the previous two decades, and settle in Rapallo, where Pound and Dorothy had moved from Paris four years earlier. They found, on arrival there in 1929, a rather more complicated situation than they’d anticipated. Shortly after the shift to Italy, Pound’s mistress, Olga Rudge, had given birth to a daughter, Mary, in July 1925, in the Italian Tyrol; the baby was almost immediately handed over to foster parents to be brought up in the mountain village of Gais. The following year Dorothy had produced a son, Omar, who had been just as summarily dispatched, first to a Madame Collignon who lived just outside Paris (she ‘has two children of her own,’ Dorothy assured her puzzled in-laws, ‘and knows all about bottles and milk and such like’), and then to an ex-Norland nanny in Felpham, Sussex. Pound had concealed Mary’s existence from his parents, and his letter announcing the birth of Omar was elliptical in the extreme:

Dear Dad

next generation (male) arrived.

Both D & it appear to be doing well.

Ford going to U.S. to lecture in October.

Have told him you wd. probably be glad to put him up.

more anon,

yrs

Months later his parents were still pumping him for basic information, such as the date of Omar’s birth.

Their presence in Rapallo made it hard for Pound to maintain his stonewalling. He confided the secret of Mary’s birth to Homer, and took him to visit her in Gais. If Isabel was told, it seems she simply decided to ignore the fact, distressing and inconvenient as it was. A decade later, in the summer of 1939, his parents seem finally to have been given an explanation for Pound’s indifference to Omar, who was by now at prep school in Bognor Regis.* In her memoir of Isabel and Homer that prefaces this volume, Mary tactfully but unequivocally makes clear her opinion that Pound was not Omar’s father, and suggests that it was the revelation of this that prompted two bewildered letters from his parents: ‘Dear Son,’ Isabel wrote on 31 July 1939,

The situation is to me amazing – one disloyalty provokes another is understandible but why continue the deception so many years one cannot transfer affections –

Three days later Homer wrote:

My Dear Son.

A clap of Thunder out of a clear sky could not have been more startling than yours and D’s letters. For over 10 years we have been here. D. has been giving us Omar’s photos o k and it is hard to realise the truth. Why did you suggest our remaining? As matters have developed there is no pleasure in our continuing here.

We shall arrange to – depart –

Your Old

Dad

In the event they didn’t abandon Ezra, whose behaviour was becoming increasingly erratic, despite making extensive preparations to return to America. Homer fractured a hip in 1941, and died the following year, one hopes without having tuned in too frequently to the broadcasts that would lead to his son’s indictment for treason in 1943. Isabel survived until 1948, eventually laying aside ‘old resentments’, as Mary put it in her autobiography Discretions (1971), and moving to live with her granddaughter and burgeoning family in Schloss Brunnenburg in the Tyrol, where she died and is buried.

‘May you live in interesting times’: Pound’s life often brings to mind the Chinese proverb, occasionally attributed to Confucius, to whose teachings he increasingly looked for world salvation during his incarceration in St Elizabeths, where he gathered around him a motley crew of would-be poets, anti-semites and white supremacists. It was only five years before his death, in conversation with Allen Ginsberg in 1967, that he explicitly turned on himself for falling prey to ‘that stupid, suburban prejudice of anti-semitism’. These letters back to 166 Fernbrook Avenue, Wyncote, Philadelphia, frequently make us acknowledge the great distance Pound travelled from his suburban origins in quest of a poetry capable of wrenching the American impulse into art, though, on his own admission, he never succeeded in creating the ‘paradiso/terrestre’ imagined towards the very end of his carpet-bag of an epic – a work that very few would deny ‘soars way above the crowd’, as Homer admiringly put it. The father’s unwavering pride in his adventurous son is perhaps best captured by a remark Homer made to Louis Zukofsky when the young Objectivist visited Rapallo in 1933. Walking along the beach together one afternoon, Homer pointed out a distant figure swimming on his back half a mile from shore: ‘See that over there floating? That’s my boy!’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.