31 December 2009, Yorkshire. Call Rupert to the back door to watch a full moon coming up behind the trees at the end of the garden. It’s apparently a ‘blue moon’, i.e. the second full moon this month, which happens every two or three years. The next blue moon on New Year’s Eve won’t be until 2028 so it’s the last one I shall ever see – and it’s also the first that I ever knew about. The moon is strong enough to cast sharp shadows, with the sky blue except for occasional reefs of cloud so that with the snow still lying in drifts on the road earth and heaven seem one.

23 January. To the National where I watch the matinée of The Habit of Art. It’s a sharp and energetic performance, matinée audiences often the best and today’s helped because there are thought to be at least 130 blind people in the audience. Some of them have been up on the stage beforehand to familiarise themselves with the layout, handle the props and meet the cast, all of which helps to focus attention on the play and there’s scarcely a cough. I wait in the wings for the actors to come off then go up to the canteen and have a cup of tea with them, something I haven’t done since the play opened and have much missed.

24 January. Two boys from Doncaster have been sentenced for torturing two other boys from the same village. In sentencing them the judge gives them a stern lecture, though how much of it they understand must be debatable. It’s a shocking story, with one of the victims having been battered almost to death. David Cameron is quick to move in and claim the crime is evidence of ‘a broken society’, conveniently ignoring the fact that Edlington, the village in question, is smack in the middle of what was a mining community, a society systematically broken by Mrs Thatcher. As with the Bulger case the tabloids make a determined effort to find out the identity of the culprits, the crime frequently described as ‘unimaginable’. I don’t find it hard to imagine at all. When I was eight or nine I used to play torture games with two other boys at my elementary school up on the recreation ground in Armley. I would pretend to whip them or they me and with a forwardness that I never afterwards enjoyed was always the one to instigate the games. At ten I went to a different school and thereafter became the shy, furtive, prurient creature I was for the rest of my childhood.

10 February. Finish with some regret Frances Spalding’s book on the Pipers, John and Myfanwy, the latter figuring in The Habit of Art where she is to some extent disparaged. I’ve always been in two minds about Piper, liking him when I was young with his paintings ‘modern’ but representational enough to be acceptable, a view I trotted out years later when Romola Christopherson was taking me round Downing Street. ‘I suppose for Mrs Thatcher,’ I sneered, ‘Piper is the acceptable face of modern art,’ not realising that at that moment the lady herself was passing through the room behind me. Some of his abstracts I like, particularly a collage, Coast at Finisterre (1961), which is illustrated in the book, and some of his Welsh landscapes. I don’t care for his stained glass, though churches are always proud when they have a Piper window, the latest (and no more pleasing than the rest) glimpsed at Paul Scofield’s memorial service in St Margaret’s, Westminster. For all that, though, the book is immensely readable, drawing together so many strands of the artistic life in the 1930s and 1940s – K. Clark, Ben Nicholson, Betjeman and all the stuff to do with the genesis of the Shell Guides. Odd to think of Piper’s gaunt figure sketching in my own Yorkshire village, the paintings he did there reproduced (not plain why) in Osbert Sitwell’s Left Hand, Right Hand and now at Renishaw.

14 February. I am said in today’s Independent on Sunday to be ‘pushing 80’ with a photograph (taken at 70) in corroboration. The article is about the decline of Northern drollery, of which I am an example.

I pass the house in Fitzroy Road with the blue plaque saying that Yeats lived there but with no plaque saying that Sylvia Plath also died there. I look down into the basement where Plath put her head in the gas oven. And there is a gas oven still, only it’s not the Belling or the Cannon it would have been in 1963 but now part of a free-standing unit in limed oak.

It was this house where Eric Korn heard someone reading out the plaque as being to ‘William Butler Yeast’. ‘Presumably,’ Eric wanted to say, ‘him responsible for the Easter Rising.’

17 February. Stopped by a man outside the post office in Regents Park Road who fishes in his wallet and shows me a note I sent nearly 50 years ago to Bernard Reiss, the tailor in Albion Place in Leeds who made me my first suit in 1954. The note is about two 7/6 seats which I’d booked him for Beyond the Fringe, the man showing it me Bernard Reiss’s nephew. I tell him about the suit, which was in grey Cheviot tweed, the waistcoat of which I still have and which I took to show Mr Hitchcock at Anderson & Sheppard before they made me a suit last year. My first suit and probably my last.

3 March. Lunch at L’Etoile with Michael Palin and Barry Cryer, Elena Salvoni still presiding there at lunchtime and though she’s 90 not looking much different from when I first got to know her at Bianchi’s in the 1960s. Barry as usual fires off the jokes which are almost his trademark but today he also talks about how, when he was a young man in Leeds, he suffered badly from eczema and used to be swathed in bandages, face included. On one occasion he went out like this into the streets of Leeds but nobody stared at him, so correctly did people behave. He even went into a shop, looking, as he said, like the Invisible Man and the woman serving took no notice, just saying: ‘Well, it’s a bit better day.’ I ask him how he got rid of it and he says it went soon after he met Terry, his wife, so that he attributed it to the stresses of being young (and, I imagine, with eczema, unloved) and living in a bedsit with all the hardships of his young life. While he was in St James’s one of the patients on his ward hanged himself in the toilets, presumably driven mad by the intolerable itching. Michael P. is as kindly as ever and me as dull, three old(-ish) men having their lunch, next stop the bowling green.

10 March. To Durham where there are not many visitors this Wednesday morning and more guides than there are people to show round. See the line of Frosterley marble inset in the floor of the nave, the limit beyond which women were not allowed to approach the shrine of St Cuthbert behind the high altar with its wonderfully spiky Neville screen, which, when I came before, I took for some 1950s Coventry Cathedral-like installation and not a genuine 14th-century reredos minus its statues. Struck, though, as then by the marble hulks on top of the Neville tombs, which, as R. says, are more representative of dead and butchered bodies than their intact representations can ever have been. Previously these tombs, mutilated and covered in ancient graffiti, were said to have been casualties of the imprisonment here of Scottish prisoners during the aftermath of the Civil War. The new notes in the cathedral’s leaflet now specifically disavow this without at the same time explaining how such radical mutilation occurred. This is somewhat mealy-mouthed, and rather than the fruits of some breakthrough study of the circumstances of the Scots’ incarceration, their absolution sounds like political correctness. A good example of changing taste is that Pevsner, writing in 1953, says of the nowadays perfectly acceptable rood screen by George Gilbert Scott, ‘It should be replaced,’ and the faux-Cosmati pulpit similarly. Apropos guides we are using Henry Thorold’s Shell Guide to County Durham written in 1980 which recommends a visit to Finchale (pronounced Finkle) Priory set in a bend of a river just north of Durham, of whose remoteness and unspoiled beauty Thorold gives a lyrical description. No more – and when we eventually track it down on the far side of a housing estate it turns out to be on the edge of a caravan site that comes to within a few feet of the abbey. Visiting Byland we’d remarked, coming away, on the variety of lichens growing in the ruins, the stones blotted with their grey patches. In Durham I notice similar lichens, particularly on the paths leading up to the south door, only later realising it wasn’t lichen but chewing gum.

23 March. That Ted Hughes should have got into Poets’ Corner ahead of Larkin wouldn’t have surprised Larkin, though he must surely have a better claim. Two deans back, and not long after Larkin’s death, I remember Michael Mayne saying that Larkin had earned his place on the strength of ‘Church Going’ alone. Though Hughes fits the popular notion of what a poet should be, many more of Larkin’s writings have passed into the national memory.

31 March. Remember – I’m not sure why – when I was at school and doing the (somehow obligatory) amateur dramatics I was in William Douglas Home’s The Chiltern Hundreds with one of my lines ‘That’s the cross I’ve got to bear.’ A devout Christian at the time I felt I couldn’t say this line, my notion of piety having much more to do with dubious issues of conscience like this than with practical Christian conduct. Anyway I made my protest and the producer ‘Charlie’ Bispham, the chemistry master (dapper figure, pencil moustache), was gratifyingly sarcastic, thus assuring me I was a martyr for my faith. But I didn’t say the line – and probably a lot of others as I was never very sure of the text. Twerp, I think now, marvelling at how I could survive the embarrassment, not my own (I was a Christian after all) but that of the rest of the cast.

7 April. The open mouth of Chelsea’s Frank Lampard, having scored a goal, is also the howl on the face of the damned man in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment.

16 April. The row over Lord Ashcroft’s non-dom status seems to have died down. Nobody, I think, noted that it was the reverse of the row that triggered the War of American Independence. In 1776 the rallying cry was no taxation without representation whereas with Lord Ashcroft (and the other non-doms) it is no representation without taxation, i.e. why should he or anyone have a voice in the making of legislation if he or she does not pay taxes.

19 April. Apropos the transport shutdown due to the volcanic cloud there have been the inevitable outbreaks of Dunkirk spirit, with the ‘little ships’ going out from the Channel ports to ferry home the stranded ‘Brits’. It’s a reminder of how irritating the Second War must have been, providing as it did almost unlimited opportunities for bossy individuals to cast themselves in would-be heroic roles when everybody else was just trying to get by. ‘Brits’ – so much of what is hateful about the world since Mrs Thatcher in that gritty hard little word.

2 May. Several of the obituaries of Alan Sillitoe who died last week mention how, when as a child he was being hit by his father, his mother would beg ‘Not on his head. Not on his head.’ My father was a mild man and seldom hit my brother or me but when he did my mother would make the same anguished plea. ‘Not on their heads, Dad.’ It’s a natural enough entreaty, though one that might be taken to have premonitory undertones: if these small boys were ever to climb out of this working-class kitchen and make something of themselves a good, undamaged head was what they were going to need.

12 May. For all the Lib Dems are in the cabinet I imagine there will be another cabinet somewhere which does not include them and where, once on their own, the Tories can come clean … or talk dirty. But then, this is what cabinet government has always been like: the cabinet and the real cabinet; it doesn’t need the excuse of a coalition.

I’ve always found tattoos hard to understand and even to forgive. Afflicted quite early in life with varicose veins I thought them both an embarrassment and even a stigma. Theirs is the same grey-blue as a tattoo and that anyone would voluntarily do to themselves what nature had done to me I found incomprehensible.

As always at signings when I’m faced with a seemingly endless line of nice, appreciative readers, most of them women, I come away thinking the writer I most resemble is Beverley Nichols.

14 May. Obituary in today’s Guardian of Gerald Drucker, veteran double bass player and for the last 30 years principal bass of the Philharmonia. When I was a boy Leeds had its own orchestra, the Yorkshire Symphony Orchestra, which gave concerts every Saturday in the town hall. A group of us from the sixth form used to sit behind the orchestra (seats sixpence) and always behind the double basses. Drucker was a young man then but quite heavily built, a cross between Alfred Marks and the actor who played One-Round in The Ladykillers, he and his instrument well suited. According to the Guardian he’d already had a varied career before he landed up in Leeds, including playing for Xavier Cugat at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York. Cut to 40 years later, when I saw him in the Festival Hall bookshop. I went up to him and stammered out my appreciation of that time in the 1950s, saying how much the orchestra had meant to me then. For someone who’d gone on to become principal bass of the Philharmonia and probably a good deal else, his time in Leeds can hardly have been a notable episode in his musical career, and thinking that this earnest middle-aged man babbling about Leeds must be wanting his autograph (though hardly a common occurrence in the lives of bass-players) he took fright and fled the shop. I’ll remember Drucker, though, together with other basses laying into the opening of Gustav Holst’s ballet music for The Perfect Fool, one of the rare opportunities when they could briefly take centre stage.

17 May. A week after Mr Hague is appointed foreign secretary the police presence (two heavily armed patrolmen) has not been withdrawn from David Miliband’s house just up the road. I pass the house nearly every day and could have asked, but fear the police might shoot me in the interests of health and safety. It was never clear to me whether the force was protecting the property or the person, as Miliband could be seen, seemingly untailed, striding round Primrose Hill (and indeed the world) while the brace of bobbies still hung doggedly about his doorstep. When they do eventually depart the first casualties will be among the cyclists of whom, judging from the bikes leaning on the railings, there are many in the street. Having had my own (locked) bike recently nicked from outside my house (which has no police presence) I’d advise them to get their bikes inside sharpish.

23 May. I’m coming to the end of Wolf Hall, Hilary Mantel’s novel, the first of two about Thomas Cromwell. Rich and vivid and teeming with life it’s a monumental work and some, at least, of one’s admiration is for Mantel’s sheer industry. Presented as very much a modern sensibility Cromwell recoils from, or is anxious to avoid, cruelty, a restraint he learned in the service of his first master, Wolsey. He’s particularly concerned about the penalties inflicted on those of his own reformist way of thinking. But cruelty is indivisible. Though he is repelled by Thomas More for the torture he personally inflicts on heretics, Cromwell is made to dismiss the Carthusians butchered at Tyburn just as ‘four treacherous monks’.

More is the villain of this first volume. Mantel admits to being a contrarian, and is unwilling to give More any credit at all for moral courage so that one begins to feel the portrait of Cromwell is as skewed as Robert Bolt’s (or Peter Ackroyd’s) is of More and for the same reason, both men human and therefore venial when embosomed in their respective families.

Set against this massive work one’s objections seem petty, and it’s a tribute to the power of the novel that one discusses it as if it were history or at least biography, with one’s misgivings elusive and lost in the undergrowth of the novel’s intimate conjecturing. Still, one keeps coming up against inequities: Clerke and Sumner, two heretic scholars, starved to death in the cellars of Wolsey’s Cardinal College; ten of the Carthusians who were not executed at Tyburn were starved to death in Newgate; Clerke and Sumner get a mention but not the monks. This is perhaps an author’s privilege and one has to keep reminding oneself this is a novel, but time and again Mantel seems to let her hero (and so far he is a hero) down lightly. A little further down the road will come the punishment of Friar Forrest, roasted slowly to death in a gala ceremony at which Cromwell presided. One waits to see how Mantel deals with this.

I have to admit, though, that I find it hard to read about the middle years of the 16th century certainly with any pleasure any more than I can enjoy a history of the Third Reich, say, or a programme on Stalin’s Terror. One element in Wolf Hall’s success as it is an element in the success of the work of Antony Beevor is the regular and unflinching presentation of horror. There may be cornflowers on Cromwell’s desk but this is a novel about torture, tyranny and death.

11 June. Drive round to Camden Town to shop and go to the bank where I draw out £1500 to pay the builders. I put the money in an envelope in my inside pocket and then cross the road to M&S where I shop for five minutes or so. At which point two middle-aged women, Italian by the look and sound of them, tell me somebody has spilled some ice cream down the back of my raincoat. I take off my coat and they very kindly help me to clean it up with tissues from one of their handbags and another man, English, I think, big and in his fifties, goes away and comes back with more tissues. The ice cream (coffee-flavoured) seems to have got everywhere and they keep finding fresh smears of it so that I take off my jacket too to clean it up. No more being found I put my jacket on again, thanking the women profusely though they brush off my gratitude and abruptly disappear. I go back to the car, thinking how good it is there are still people who, though total strangers, can be so selflessly helpful, and it’s only when I’m about to get into the car that I remember the money, look in my inside pocket to find, of course, that the envelope has gone. The women or their male accomplice must have seen me in the bank or coming away from it and followed me into the store. I go back to M&S, tell security, who say they have cameras but are not sure if they were covering that particular spot (they weren’t). They ring the police while I go back to the bank, who also have CCTV which the police will in due course examine. I give my details, and my address and phone number, to a constable who, when I get back home, duly rings with the incident number. Ten minutes later, less than an hour after it has occurred, the doorbell rings and on the doorstep is a rather demure girl: ‘My name is Amy. I’m from the Daily Mail. We’ve just heard about your unfortunate experience.’

I close the door in Amy’s caring face, tell a photographer who’s hanging about to bugger off (‘That’s not very nice’) and come in and reflect that though the theft is bad enough more depressing is that someone in the police must immediately have got on to the Mail, neither the bank nor M&S having either my private number or the address. I just wonder how much the paper paid him or her and what the tariff is – pretty low in my case, I would have thought. The women are thought to be Romanians, and in any case were very good at their job and must have been pleasantly surprised at how much they netted and how stupid I was. Quite hard to bear is that I have to go back to the bank to draw out another £1500 or the builders will go unpaid.

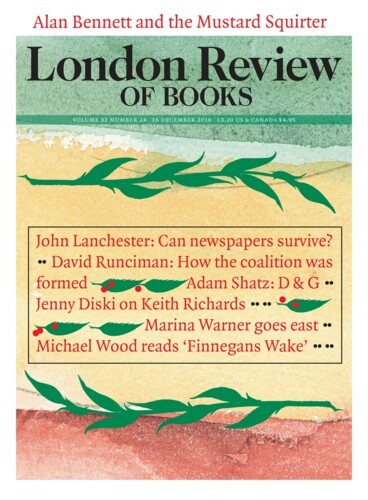

The con is a familiar one, apparently, and often pulled in Spain. It even has a name: the Mustard Squirter. Still it’s the liaison between the police and the Daily Mail that is the most depressing. Years ago when Russell Harty had been exposed in the tabloids he was being rung in Yorkshire every five minutes. His solicitor then agreed with the local police that he should have a new number, known only to the police. Ten minutes later a newspaper rang him on it.

13 June. Yesterday afternoon the Express telephoned. This morning at eight o’clock the Standard is on the doorstep. Talk to Niamh Dilworth at the National about it and tell her that the police have asked me not to dry-clean my jacket and ice-cream smeared raincoat in order to test them for DNA. She says that all they’ll be able to discover is whether it was Wall’s, Viennetta or Carte D’Or. The casualty, though, is trust, so that I am now less ready to believe in the kindness of strangers. But one has to be careful when one has been robbed. Like cancer it’s one more topic on which it’s easy to become a bore.

26 June. Apropos Prince Charles’s intervention in the Chelsea Barracks redevelopment Ruth Reed, the principal of Riba, says: ‘The UK has a democratic and properly constituted planning process: any citizen in this country is able to register their objections to proposed buildings with the appropriate local authority.’ This is disingenuous. The planning process is and always has been weighted against objectors who, even if they succeed in postponing a development, have to muster their forces afresh when the developer and the architect come up with a slightly modified scheme. And so on and so on, until the developer wins by a process of attrition. Furthermore Ms Reed, in her role as trade-union leader for her profession, ignores the dismal record of mediocre architecture which has ruined so many English towns and continues to do so. Anyone, even the sultan of Qatar, who stands up to this collection of mediocrities gets my vote. And all the talk of HRH exceeding his constitutional rights is tripe.

30 June. One of the umpteen competing narratives thrown up by my ‘unfortunate experience’ comes in the greengrocer’s this morning when an Australian woman tells me how she had been at Glyndebourne, presumably somewhat dolled up, when what she describes as an ‘over-effusive Latin type’ (not, she thought, a fellow operagoer) had insisted on kissing her hand. Retrieving it she found he had in the process managed to grease her fingers with a view, presumably, to slipping off her rings – perhaps greasing her hand when he took it and, as he kissed it, hoping to take her rings off with his teeth.

9 July. In the rumpus over the cutbacks in school building, the errors in the schools listed and the (quite mild) humiliation of Michael Gove there’s been no mention that I’ve seen about private education. I may have missed it, but since we’re all supposed to be tightening our belts why not the public schools? Don’t they have a contribution to make, subsidised as they are in all sorts of ways by the government? Soon after taking office Gove deplored the stratification of education in England, while managing to say nothing about the most obvious stratification of all, namely the public schools that form the top layer and will go on doing so.

15 July. Finish reading Adam Sisman’s biography of Hugh Trevor-Roper, a wonderfully absorbing book. Seeing Trevor-Roper in Oxford in the 1950s I thought him extraordinarily young, so that when he was made regius professor in 1957 he still looked like an undergraduate. His face always seemed to me to have a flattened nose which gave him a slightly (and fittingly) pugnacious air. He was a lifelong sufferer from sinus trouble and at one point had his septum removed so this may account for it. Happy to see his predecessor as regius professor, V.H. Galbraith, mildly rubbished. I remember him as a small bullying man with highly polished boots; he thought the world of Maurice Keen (quite rightly) but took me for a fool and more or less said so. He’d apparently served with distinction in the First War and been decorated for gallantry by the French, the gallantry including driving his men over the top at the point of a revolver which, had I known it, would have made me like him even less. Another recurrent figure is that fugitive from Mount Rushmore Gilbert Ryle, who sounds, in his wartime days anyway, to have been very funny, saying of Trevor-Roper’s supposedly tactful politicking, ‘Many a bull emerging from a bloodstained china shop has congratulated itself on its Machiavellian diplomacy.’ But as always when I read about Oxford I’m so thankful I never ended up a don.

25 July. A week’s holiday in Yorkshire begins with an appearance at the Harrogate Festival. It’s also a 90th-birthday celebration for Fanny Waterman, the founder of the Leeds Piano Competition, one of whose ex-pupils is doing the first half of the programme. This is scheduled to last for 40 minutes but, entranced by his own music-making, the pianist goes on for well over an hour while I fume in the dressing-room. I don’t mind curtailing my performance but this means I won’t get my supper until well after 11. Some of this truculence feeds itself into my stint, which begins with a speech in favour of the NHS from an early play of mine, Getting On. This is well received and encourages me to say how, whereas nowadays the state is a dirty word, for my generation the state was a saviour, delivering us out of poverty and want (and provincial boredom) and putting us on the road to a better life; the state saved my father’s life, my mother’s sanity and my own life too. ‘So when I hear politicians talking about pushing back the boundaries of the state I think’ – only I’ve forgotten what it is I think so I just say: ‘I think … bollocks.’ This, too, goes down well though I’ll normally end a performance on a more elegiac note.

27 July. To Mount Grace, the Carthusian monastery, visited once before 15 years ago though today it seems much larger, the scale of it perhaps accentuated by the small size of the cells surrounding the cloister. The irrigation system still survives, with the individual closets connected by a channel running along the back of the cells and another channel irrigating the individual kitchen gardens which were a feature of each cell, the whole place delightful and making it understandable why they were queuing up to become monks here right until the eve of the Dissolution. The kitchen gardens are very much overgrown, some of them planted with authentic medieval herbs including tansy, which smells disgustingly of pee. It’s an English Heritage site and R. suggests that rather than the medieval jousting and other olde japeries which are regularly laid on these days it would be far more of an attraction if all these adjoining cell gardens were run together and planted out as allotments. Something similar is currently being tried at one or two National Trust properties but it’s what Mount Grace would be ideally suited for.

13 August. When I go up on the train to Leeds I’ll generally sit in the same seat, often in front of the same businessman, who must also be a creature of habit. We chat, though without really knowing one another, and today as we’re getting out at Leeds he tells me that he’s been staying with friends in East Anglia. He had mentioned that he often sees me on the train whereupon his hosts had looked rather sheepish. It turns out that at their work, office or whatever they have a sweepstake to which they contribute every month with the participants drawing various well-known names from a hat; the winner being the one whose named notable is the first to die. I am one of their names.

They haven’t had a win for some time, their last bonanza coming with the death of Spike Milligan, who died in an otherwise fallow period so the pot had grown quite large, which it isn’t always: if two names die within a month or two of each other when the pot hasn’t had time to accumulate the winner will only get a paltry sum.

I laugh about this when he tells me, but I find it depressing to think that even in a lighthearted way there is at least one family in the kingdom waiting (if not longing) for my death. I don’t know what the monthly contribution amounts to but were it substantial I suppose a game like this might even lead to murder – even if it’s only a murder such as occurs in Midsomer.

It’s also another instance of ‘write it and it happens.’ Towards the end of The Habit of Art Humphrey Carpenter tells the ageing Auden and Britten that they have reached that stage in their lives when even their most devoted fans would be happy to close the book on them: no more poetry, no more music. Enough. It’s not the same but still, the thought of anyone who for whatever reason would be happy to see the back of you is disturbing even if it’s a joke. Good plot (or sub-plot) though.

24 August. To UCH for an X-ray of my hip. I leave home at 11.45 a.m. and am back there by one o’clock. This is because it’s a walk-in facility which, on the several occasions I’ve had to use it, has been of exemplary efficiency. There is speed, privacy and one goes at one’s own convenience – all of these regularly advertised as the benefits of private medicine. I have used both in the past and if need be will do so again but in this regard, as in so many others these days, the NHS is better.

3 September. Primrose Hill never fails to surprise. Today I am walking up Chalcot Road along the edge of Chalcot Square when I see an old lady having difficulty walking and just making it to a bollard where she rests for a moment. She’s spectrally thin and has difficulty speaking, but she manages to gasp out that she’s looking for Cahill Street and that her son is touring round in his car also looking. I offer to go home and fetch an A to Z while she sits on a seat, though the seat is already occupied by a young man who is taking no notice of this little drama. Suddenly the woman straightens up and starts speaking in a man’s voice and I see that, having been wholly convincing as an old woman, she is actually quite a young man. Still, though, he claims not to know where he is, saying that he keeps having ‘these do’s’ and that the last thing he remembers was being in Bromley and where is he now? Another passer-by has stopped to help and I decide it’s getting a bit too complicated for me so I go on my way.

Ten minutes later I’m walking up the street and the old lady/young man comes running up to me together with the one who’d been on the seat, who, it turns out, had been filming the encounter. Surprise, surprise they’re actors, trying to put together a pilot for BBC3. This is a shame if only because it makes the whole encounter more ordinary. Afterwards I think back to my last unsought encounter in M&S when my pocket was picked, and had this been a similar scam it would have been just as easy to pick my pocket again as I’d helped the ‘old lady’ to the seat. This had never occurred to me. Streetwise I’m not.

28 September. One drawback of writing about Auden is that if one does hit on something striking to say or turn a nice phrase it’s assumed by the audience that it was Auden who wrote it, the text just taken to be joined-up Wystan. Of course this works both ways and critics in particular are, I think, nervous of taking exception to stuff that I say in case I’m actually quoting the poet.

21 October. Find in the bookshelf a copy of The Private Art: A Poetry Notebook by Geoffrey Grigson, which I must have read years ago and forgotten. Tipped in, as booksellers say, is a letter from a woman about Louis MacNeice, on whom I’d done a TV programme and who was a friend of Grigson’s. She had known Grigson and he had told her how en route to Fawley Bottom to have lunch with John Piper one Sunday in 1939 he and MacNeice had stopped in a field to picnic and listen to Chamberlain’s broadcast and the declaration of war.

The story seemed odd. If they were going to lunch with the Pipers why stop for a picnic, particularly when Myfanwy Piper was a noted cook? And why at 11 in the morning? Interest in Grigson rekindled I track down a copy of his Recollections (1984) to find that MacNeice had had nothing to do with it, but that on the eve of the declaration of war Piper had spent the night at Grigson’s cottage in Wiltshire. In the morning they drove off to have lunch with John Betjeman at Uffington, stopping on the way and ‘stationing a battery set on the yellow stubble in time to hear Chamberlain say we were at war. All three of us were old enough to remember catchphrases from World War One. John Betjeman poured out sherry and with the Betjeman half-smile said, “For the Duration.”’ Grigson was always unpleasingly proud of his independence of mind and the memory didn’t soften his attitude to the future poet laureate whom he describes as ‘a kindly and forgiving man; but I detested and still detest his verses, or most of them’.

10 November. A routine colonoscopy, though it never is routine, with no telling what’s round the next corner. Today it’s a little fairy ring of polyps, innocent enough but ruthlessly lassoed and garrotted by the radiographer lest in two or three years’ time they grow up to be the ‘nasties’ he’s on the lookout for but thankfully does not find. On the way down we pay a reverential visit to the site of my original operation before, as he puts it, ‘cruising down’. Unaccountably this takes me back to the amusement park on the front at Morecambe in the first year of the war when Dad took my brother (nine) and me (six) on the Big Dipper. As Big Dippers go it was pretty tame, though far too scary for me, who never went on it (or any other) again, but there was just one bit I enjoyed: when all the ups and downs were over, the train briefly coasted along a high straight stretch behind the boarding houses and with a view over the sea before it gently rattled down the long incline to the platform and the end of the ride. And that was what the last bit of the colonoscopy reminded me of 70 years later.

2 December. Thinking of the injunctions – they were hardly advice – that Mam used to deliver when we were young. When I went off to university she said (and often added as a postscript to her letters) ‘Don’t stint on food,’ meaning that if I had to economise it shouldn’t be on meals. I was never in such straits that I had to make a choice, but, had I been, food (rather than books, say) would have come first anyway, though not because she had said so. Another injunction that was almost a mantra was said whenever my brother or I were on the point of leaving the house: ‘Don’t stop with any strange men.’ This was another piece of advice that I never had any cause to heed, though in retrospect I wonder if it helped to make my youth as hermetic as it was, as Mam would still be saying it when I was in my twenties and patrolling the streets of Headingley in the solitary walks I had been taking every night since I was 17.

There were other more mundane prohibitions, particularly in childhood, generally to do with avoiding TB. We were told never to share a lemonade or a Tizer bottle with other boys; we should keep the sun off the back of our necks nor were we allowed ever to wear an open-necked shirt until we were in our teens. We never ate prepared food from shops, so not the beetroot bubbling in an evil cauldron in Mrs Griffiths’s greengrocer’s down Tong Road, not the ‘uggery-buggery’ pies on sale in the tripe shop or the more delectable offerings in Leeds Market. Permissible was potted meat from Miss Marsden’s genteel confectioner’s or Prest’s on Ridge Road, their respectability making them in Mam’s eyes an unlikely health hazard.

Not that it follows on, but these days I am too old to be on my best behaviour. And I’m too old not to be on my best behaviour also.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.