They gathered us in a dark-panelled windowless basement in the Foreign Office for a briefing. The year was 1966, and the group was made up of 20 or so British students selected to go to the Soviet Union for ten months under the auspices of the British Council. Plus one Australian, myself, who had managed to get on the British exchange because Australia didn’t have one. Our nameless briefer, who we assumed to be from MI6, told us that everybody we met in the Soviet Union would be a spy. It would be impossible to make friends with Russians because, in the first place, they were all spies, and, in the second, they would make the same assumption about us. As students, we would be particularly vulnerable to Soviet attempts to compromise us because, unlike other foreigners resident in Moscow and Leningrad, we would actually live side by side with Russians instead of in a foreigners’ compound. We should be particularly careful not to be lured into sexual liaisons which would result in blackmail (from the Soviet side) and swift forcible repatriation (from the British). If any untoward approach was made to us, or if we knew of such an approach being made to someone else in the group, we should immediately inform the embassy. This was not a normal country we were going to. It was a Cold War zone.

I ended up spending a total of a year and a half in Cold War Moscow, between autumn 1966 and spring 1970. I travelled under a false identity, or that’s what it felt like: the nationality on my passport was British, not Australian; the surname was Bruce, which was my husband’s name but not mine; and, to top it off, I had decided to use my middle name, Mary, on the grounds that it could be shortened to Masha and would be easier for Russians. (Nothing came of this: I could not believe in Mary as my name, and in any case it turned out that all educated Russians knew the name Sheila – which had an easy diminutive, Shaylochka – because they had read C.P. Snow.)

It was impossible to live in the Soviet Union as a foreigner and not become obsessed with spying. (If anyone doubts this, read Michael Frayn’s wonderful novel The Russian Interpreter, published the year I first went to Moscow.) ‘Do you think X is a spy?’ we were always asking each other about new Russian acquaintances, and sometimes about each other. It was a question that went the other way, too. ‘Are you a spy?’ ‘Ty shpionka?’ I was asked by an ingenuous schoolgirl in Volgograd. I said no, of course, but it wasn’t an answer I was 100 per cent sure about. What exactly was a spy, anyway? One could view it as a narrow professional designation, but the Soviets often used it to refer to any foreigner who tried to find out things they wanted to hide (which were many, and not always predictable). We students had been through an official government briefing, would perhaps be debriefed at the end, and were expected to write a detailed final report to the British Council. Could one be a spy without knowing it? Or a spy by virtue of involuntary association with spies and ex-spies (this was a particular worry for me, since there seemed to be so many of the latter at St Antony’s, my Oxford college)? We thought anxiously about the case of Gerald Brooke, a British teacher sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for ‘subversive anti-Soviet activity’ the previous year, hoping he had been a real spy and not someone like us.

I wondered later if our London briefer knew how wrong he was about the impossibility of making Soviet friends. In fact, almost everyone in our group made friends, close ones, but perhaps we were all too prudent (I certainly was) to mention this in our final reports. You made only a few friends, as the Soviets themselves did: too wide a circle was seen as dangerous and promiscuity in friendship strongly discouraged. But the friends you had were friends for real, like family (if one had been lucky enough to have had that kind of family), offering unlimited practical as well as spiritual support. The warmth of Russian friendship was a source of perpetual wonder to us, something beyond our experience as well as our expectations.

There were various ways of acquiring Russian friends. Some foreign students acquired their Soviet family by having a love affair (these were common, despite the briefer’s warnings), and, as a result, being adopted by the lover’s family. That ‘as a result’ was another odd thing: Soviet families were close, and the adolescent’s challenge to his or her parents’ values was something that seemed to have passed them by, so it was natural that a lover would become part of the family (also, as the lovers usually had nowhere to go but the family apartment, pragmatically necessary).

I acquired my family through my research. My topic was Anatoly Lunacharsky, the Bolshevik intellectual who was the first Commissar of Enlightenment after the Revolution. Lunacharsky, I knew, had a daughter (she had edited some of his work), and I asked my adviser if it would be possible to meet her. We all had these advisers, some of whom were cautiously helpful and others merely watchdogs. Mine, a literary scholar who had reputedly made his name unmasking Jewish scholars with Russian names in the ‘anti-cosmopolitanism’ campaign of the late Stalin period, seemed to be the watchdog type, but since I had no other way of finding Lunacharsky’s daughter (there were no telephone directories), I asked him anyway. His response was surprising. Abruptly shifting from his official register of right-thinking clichés, he launched into a stream of malicious gossip about the Lunacharsky family. Lunacharsky’s young second wife, a Jewish actress, had caused all sorts of trouble and embarrassment. Her brother, Igor Sats, had been the only person present when Lunacharsky died in Menton in 1933, and could well have murdered him (I wondered at the time if I had understood him correctly, but later heard the same unfounded rumour circulating in the Russian diaspora in California). The daughter of the second marriage, Irina, was not Lunacharsky’s natural daughter, for all her devotion to him, but the product of the second wife’s first youthful marriage to a Jew who died fighting in the Civil War – probably, my adviser said, on the wrong side. He was willing to give me Irina’s telephone number if, in return, I would try to get access to her father’s diaries, which she was said to have in her possession but (understandably, I thought) wouldn’t let my adviser see. Then, presumably, I was to hand them over to him. Or perhaps, as now occurs to me, just tell him I had seen them, so that he could pass on to the authorities that Irina Lunacharskaya had shown secret Soviet documents to a foreign spy. I had no intention of telling him anything, but that didn’t stop me producing some (I hope) ambiguous formula of agreement and getting the telephone number.

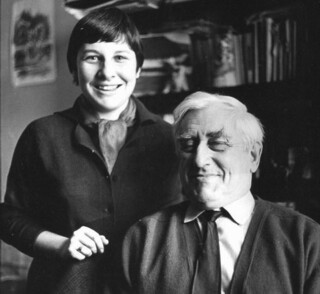

Irina was formidable: small, bristling with energy, worldly, notably elegant in the general drabness of Moscow, a fluent conversationalist and relentless interrogator. She was a science journalist by profession, but her avocation was restoring Lunacharsky’s reputation from the trough into which it had sunk since the Stalin period. To this end, she exercised vigilant control and, where possible, personal censorship over the work of Lunacharsky scholars, teasing them with her possession of the diaries, which she never allowed anyone to copy or even look at for more than a minute. A great coup in her Lunacharsky crusade had been getting his former apartment declared a museum, and acquiring for herself, in compensation, an apartment on the best street in Moscow. Khrushchev’s son-in-law Alexei Adzhubei, a good friend of hers who no doubt had some hand in this, lived in the same building. Irina’s apartment was huge – eight rooms, if I remember rightly, at a time when a family of four would have been grateful for two – and included a wonderful little hexagonal room, used as her office, filled with what seemed to be genuine 18th-century furniture and paintings. This was the room she ushered me into on my first visit, but I was too raw at the time to understand how extraordinary it was in a Soviet context. Later, on more informal occasions, we would either sit and talk in the kitchen, or, when too many family members were present to fit in the kitchen, eat meals prepared by an old retainer in the elegant dining-room. (Irina was the first person I ever knew who had a live-in servant.) On that first visit, however, it was not clear that I would be allowed to return. Irina was suspicious of me, not just as a Westerner but also as someone sent by a man who, as she wasted no time telling me, was universally known to be a scoundrel. She decided to send me along to her uncle Igor for further vetting. This was the same Igor slanderously mentioned by my adviser. Irina described him as a wise man who knew the world, which I understood to mean that if I were a spy, he would see through me.

I turned up on Igor Sats’s doorstep, nervous and rather cold in my unsuitable coat, dark green wool with gold buttons, bought at Fenwick’s and made for a British winter rather than a Russian one. The door was opened by a man in his sixties with a big nose (one could see why he was cast as First Jewish Murderer), bright white hair flopping over his forehead, and an expression that was at once wily, charming and benign. ‘A British girl wearing the uniform of the tsarist Ministry of Railways!’ he exclaimed as he ushered me in. ‘What a nice thing to see. But why have you no proper winter coat? We have to find you one.’ We never found the coat: Igor, as I later discovered, was an old socialist who was indifferent to material possessions, a point of contrast between him and Irina. But Igor had found another stray to adopt, and I had found my Soviet family.

When I later asked Igor how he knew I wasn’t a spy, he just laughed. He was an old spy himself, he used to say (using the neutral term razvedchik, rather than the pejorative shpion), having commanded a unit of army field spies during the Second World War. He maintained a benevolent interest in his former subordinates (‘my spies’) and still drank with them occasionally. He was also an Old Bolshevik, who as a schoolboy and aspiring pianist had run away from his prosperous bourgeois family to fight for the Reds in the Civil War; when the KGB wanted to ask him about me, they summoned him as a token of respect to the Party Central Committee building on Old Square instead of the Lubyanka. But according to him, it amounted to the same thing. As he told me (it was outrageous, in Soviet terms, to tell a foreigner any of this, but Igor liked being outrageous), they instructed him to maintain Party vigilance in his dealings with me and let them know of anything untoward. If I turned out to be a spy, he would be held to blame for faulty surveillance. He agreed to this. To be on the safe side, he said to me afterwards, I had better let him know about any new acquaintances so that he could check up on them (he didn’t say how). I did that on several occasions, and it was thumbs down every time. After a while I wondered whether what Igor had against these new acquaintances was that they were young men. I felt bad about one of them: in addition to cooking me an excellent whole fish in his apartment (hard to come by in Moscow), he told me that his father was in the KGB and that he would understand if, under the circumstances, I decided not to see him anymore. It seemed unkind to reward his honesty with a brush-off. But of course a clever KGB man – and there were clever as well as stupid ones – might have worked out that this was a double bluff I would fall for, so perhaps Igor was right.

As a young man, Igor had been Lunacharsky’s secretary as well as his brother-in-law, so he was an incredible primary source for my dissertation: he remembered everything, knew everybody in the Party elite, admired very few of them, and skewered each one with a deft characterisation. Perhaps this free-ranging disrespect was the secret of his survival through the Great Purges and the postwar anti-semitic campaigns, since, with a less critical view of Trotsky’s arrogance, Zinoviev’s stupidity and Bukharin’s naivety, he might have joined one of the opposition groups of the 1920s and thus sealed his fate under Stalin. In his milieu, survival more or less unscathed was not the norm: his stories of the past were full of friends who had perished, and he had a host of orphaned children to keep an eye on. When I asked him how he had managed to survive, he said it was a matter of luck, helped by his lack of ambition for high office. Igor never had a high opinion of the Soviet security services: many of his funniest stories were about absurd mistakes or incompetence, and once he was infuriated to receive a letter that had not only been clumsily opened but had had its address partly defaced; in my presence, he mailed off the damaged envelope, together with a sharp protest, to the post office. The best option in time of purges, according to Igor, was simply to vanish without telling anyone where you were going, like the friend who went south, got himself arrested for stealing chickens and sat out the Great Purges safely in jail. But Igor himself had sat them out in Moscow, keeping his head down. It was a great relief when the Second World War came and he could volunteer for active service, hoping (as I gathered) to be killed.

The war turned out to be a great time for Igor: full of excitement, adventure and human interest; dangerous, but free of the psychological pressures of peacetime on someone who, despite everything, remained a Communist. He lost all his teeth in a hard winter on the Smolensk front, but otherwise came through without significant injuries. That was in contrast to the Civil War, during which he nearly died of the wounds that kept him in hospital for several years in his early twenties and left bullets lodged in his spine. He talked more about the Second World War than the earlier one; in fact, he talked about it so much that I became almost an expert on the various fronts and multiple armies and commanders. But in the end, in 1979, it was the after-effects of the Civil War wounds that killed him.

When I met Igor, he lived on Smolensk Square on the Arbat, in a two-room apartment that had been built in the early 1930s in a spirit of communalism, with shared bathrooms and lavatories on the corridor. That turned out to be a tremendous problem for Igor’s wife, Raisa, on whom surgeons had performed a colostomy, although no colostomy bags were then available in the Soviet Union. (I was to become a skilled smuggler of colostomy bags through Soviet customs.) Raisa, who was very ill when I first met the family, lived in an L-shaped room which also contained a grand piano and, somehow, Sasha, their pianist son, when he was home. The rest of the apartment consisted of a tiny kitchen in the entrance hall (the original design must have had communal kitchens, too) and Igor’s small room off to the right. Since there was space only for a desk, a bed and a bookcase, I would sit on the wooden desk chair and Igor on the bed, a Soviet divan that rose up alarmingly in the middle and looked extremely uncomfortable. After a few years, Irina decided that this flat was impossibly difficult for Raisa, and found them another one nearby with two bigger rooms plus kitchen and bathroom. It was almost opposite the American Embassy; according to Igor, the roof of the building was used for bugging and surveillance. Only Irina would have been able to procure such a treasure as this new apartment (which Igor, ungratefully, regarded as soulless), calling in who knows how many IOUs from her well-placed friends. Privately, she said to me that if Igor had a fault (apart from womanising and drinking), it was his absurd refusal to do the things necessary in Soviet life to maintain a decent standard of living, like cultivating connections.

His stubbornness in this respect was all the more notable in that he was a member of the Union of Soviet Writers, whose members were accustomed to make heavy use of its perks and slush funds. Igor disliked writing, despite or because of being such a gifted raconteur, and did it rarely and unwillingly. His chosen profession was editor – he called himself ‘the nanny of Soviet literature’ – and before the war he had worked with Lukács at the journal Literaturnyi kritik. In the years I knew him Igor ran the criticism section of Novyi mir, famous in the 1960s as the centre of reform thinking and ‘loyal opposition’ – that is, criticism of Soviet society, culture and government from a Communist standpoint; it was the first publisher of Solzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Novyi mir was often hailed in the West as a dissident publication, the assumption being that its stance of critical Communist loyalty was just a tactic; this drove the Novyi mir people mad, not just because it was untrue but also because it was so damaging. They were always in danger of having an article pulled at the last minute, the print run reduced, an editor dropped from the board, or even losing their chief editor, the charismatic people’s poet Aleksandr Tvardovsky, famous among the troops in the Second World War for his saga of the Svejk-like Vasily Terkin. From their standpoint, the worst that could happen was to be seen as an internal ally of ‘anti-Soviet forces’ abroad.

Tvardovsky liked Igor, respected him as a true intellectual and enjoyed his company as a drinking partner; others (including Solzhenitsyn) saw him as a sinister behind-the-scenes manipulator. (There was an anti-semitic tinge to this.) Igor revered Tvardovsky, as he had done Lukács; he was the only person Igor never made jokes about. Novyi mir was always engaged in some battle with the authorities, of which I would be given blow-by-blow descriptions (some of Igor’s colleagues were not happy about this, but Igor never listened to hints: he would just stick out his bottom lip and go his own way). One of these battles was at a particularly dramatic stage just when I had to go back to Britain, and Igor promised to let me know the outcome by letter, using a simple code to confuse the postal censors: he would refer to Brezhnev as ‘Nikolai Pavlovich’, the name and patronymic of a provincial writer who was one of the Novyi mir crowd. The letter came, and it did indeed contain news of Nikolai Pavlovich – the real one, reported to be complaining of a shortage of sausage in Voronezh. Igor had forgotten about his code.

I spent my whole time in Moscow sitting on hard wooden chairs. When I wasn’t on Igor’s chair, I was at the Lenin Library or, after the first three months, the archives, where I was pursuing my own mission, which was to find out the real story of Soviet educational and cultural policy in the 1920s. Getting into the archives was an idée fixe of mine because I thought that was what a historian had to do; I was too naive to know that for a Western historian of the Soviet period this was next to impossible. Getting permission to do anything was a big problem in the Soviet Union, involving endless visits to bureaucrats who demanded ever more documents and would make you wait for hours outside their little windows and then, when you finally got to the front of the queue, slam down their shutters triumphantly (Closed for lunch!Closed for the day!Closed for repairs!Closed for ever!). But archival permissions were the worst, except perhaps for permission to marry. Not long before, the central archive administration had actually been part of the security ministry, and the contents of state archives were still considered state secrets, which foreigners wanted to get hold of in order to slander the Soviet state. Not knowing how hopeless my quest was, for months I tramped round Moscow asserting in bad Russian my rights (the very word must have made them laugh) as an exchange student and scholar to various unresponsive officials. I remember going to the Central Party Archives, whose location I was not supposed even to know, and putting this argument. I received a swift and effective rebuff: ‘What right have you to see Party documents? Are you a member of the Communist Party?’

The state archives were a little more accessible, since foreigners working on pre-revolutionary history had been let in for the past few years, and finally I got permission to work there. How this happened I don’t know: I had asked my adviser to intercede for me (perhaps rashly, since I never procured Lunacharsky’s diary for him and was close-mouthed about my friendship with Irina and Igor), but all he did was tell them not to admit me, or so I was told later by a friendly archivist. There was a special reading room for foreigners, most of them from ‘fraternal’ (socialist bloc) countries, not capitalists like me. The entrance was on a different street from the entrance for the Soviet reading room, and the fragile-looking cloakroom attendants, barely capable of lifting briefcases and heavy coats, were said to be Gulag returnees. I was told this by a savvy fraternal foreigner from Poland, working on the 17th century because who in their right mind would try to work on the 20th. We weren’t allowed to go to the snackbar or cafeteria because that would have meant wandering unsupervised around the building; instead, kind-hearted supervisors (dezhurnye, always women) made tea for us and allowed us to eat sandwiches at our desks, dropping crumbs on the state secrets. Even foreigners had to be allowed to go to the lavatory, however, and that was how I scored my big break. As my fraternal friend informed me, the director’s (unmarked) office was on the way to the lavatory. So when the archivists told me after a few weeks that I had exhausted all available materials, I burst into his office unannounced and put my case. He listened for a minute or so and said flatly ‘No,’ at which, to my great chagrin, I burst into tears. This was the best thing I ever did in my quest for archives. ‘Grown-ups don’t cry,’ the director said patronisingly. Then, with a look of infinite self-satisfaction – the occasional arbitrary granting of bureaucratic favours being even more fun than the usual surly refusal – he picked up the phone and laconically instructed someone to ‘give her some more.’

They never did give me (or any of the capitalist foreigners) the catalogues which would have allowed us to find out for ourselves what materials the archives contained; instead, everything had to be selected and ordered by an archivist on the basis of conversations with the scholar about what he or she needed. This made for a wonderful guessing game: might the institution you were interested in have kept stenographic reports? Protocols? Protocols with documentary attachments? If you got the term right, you might get the material, or not as the case might be. And exactly which bureaucratic institution was it that would have stored the information you wanted? As a crash course in bureaucratic organisation, there was nothing better than working in the Soviet archives. And, after a while, if they thought you were a hard worker and therefore a real scholar (not a spy), the archivists would cautiously begin to help you. Once, out of the blue, when at the postdoctoral stage I was working on Soviet industry, they delivered a file I hadn’t requested on the industrial use of convict labour, a topic completely off limits for foreigners. I thought it was a mistake – the file’s label was innocuous – but years later, during perestroika, I met the archivist in charge of this section (too senior for me ever to have come across in the old days) and she said: ‘Weren’t you astonished when you got that file? It was my little present to you, you were such a good worker and so conscientious!’

That word ‘conscientious’ (dobrosovestna) meant that her intuition told her I was harmless, a real scholar, not a muck-raker or a spy. In other words, her private classification of me was not ‘bourgeois falsifier’ but perhaps something milder, like ‘so-called-objective bourgeois historian’. Most Western historians were categorised as ‘bourgeois falsifiers’, the most notorious being the American scholar Richard Pipes, known for his anti-Soviet politics (he was later national security adviser on Soviet and East European affairs under Reagan), who got a whole book to himself (Mister Paips falsifitsiruet istoriiu). I was quite critical of American Sovietology myself, though when it came to falsification, the Soviets had the edge. There was a deadening predictability about both American and Soviet writing on Soviet history, the one seemingly a mirror image of the other. On any given topic, the Soviet historians would say that the Communist Party, free of internal doubts or dissent, had planned every detail of the ‘progressive’ policy, which turned out to be a smashing success. American scholars, agreeing that the Party planned every detail, would call the policy misguided and ideological, and judge it a disaster. I always thought there must be some more interesting way of interpreting the Soviet Union than simply reversing the value signs in its propaganda. And the thing that first struck me – that should have struck anybody working in the archives of the Soviet bureaucracy – was that the Soviet leaders didn’t know what was happening half the time, were good at throwing hammers at problems but not at solving them, and spent an enormous amount of time fighting about things that often had little to do with ideology and much to do with institutional interests.

Soviet analyses ignored institutional interest because they had no concept for it; American social scientists, who had a concept for it in democratic contexts, rejected it in the Soviet case because they defined that state as ‘totalitarian’. I was pleased by my discovery, and at the same time amused by the thought that scholars develop institutional interests as well: if you give a scholar just one bureaucratic archive (education, in my case), they will tend to see things from the perspective of that institution, even to take its side. One of my fantasies – along with importing a branch of Marks and Spencer and a Penguin bookshop to Moscow – was that one day the Soviets would realise this and give Western scholars access to the most taboo of Soviet archives, the NKVD’s, so that the scholars would stop slandering this fine institution and see things from its perspective: the Central Committee cadres department reassigning any Gulag officers who showed signs of competence and sending the Gulag administration nothing but duds, the difficulties in setting up native-language kindergartens for Chechen deportees to Kazakhstan, and so on.

You couldn’t get into NKVD archives (you still can’t: it’s one institution that didn’t lose control of its archives come regime change). Nor could you find out much about topics like the Great Purges by consulting the public catalogues in Soviet libraries. Still, there were treasures even in those catalogues, providing ecstatic moments of serendipitous discovery. Once, trawling through the catalogue of the social sciences library under the heading of ‘Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Congresses’, I came across something with the bland title ‘Material’. When I ordered it, it turned out to be a numbered copy of a transcript from the OGPU (the predecessor of the NKVD) of its interrogations of ‘bourgeois wreckers’ in 1930. It was marked ‘Top Secret. For Congress delegates only’, so I suppose a delegate had deposited it in the Communist Academy library, which after the academy’s dissolution served as the foundation of the social sciences library. On another occasion, I found prewar telephone directories, listed by title, in the catalogue of the Lenin Library. They used to publish such things every couple of years before the war (though not after), and it occurred to me that one way of estimating numbers of Great Purge victims – a topic of great speculation and few hard data at the time – might be to compare the lists of Moscow telephone subscribers for 1937 and 1939. I did not, of course, order only these years (‘1937’ on a library slip always rang alarm bells), but finally the volumes I really wanted arrived, and I set about painstakingly copying out every tenth name for a random sample. I think they saw what I was doing: for the next decade, whenever I tried to order telephone directories, I was told they were unavailable, lost or had never existed. But by this time, I had learned patience and the wisdom of Soviet citizens that nothing is for ever. When perestroika came, I got my telephone books back.

All this affected my formation as a historian: I became addicted to the thrill of the chase, the excitement of the game of matching your wits and will against that of Soviet officialdom. How boring it must be, I thought, to work on British history, where you just went to the PRO, and polite, helpful people gave you catalogues and then brought you the documents you wanted. What would be the fun of it? Knowledge, I decided, had to be fought for, achieved by ingenuity and persistence, even – like pleasure, in Marvell’s words – snatched ‘through the iron gates of life’. I thought of myself as different from the general run of British and American scholars, with their Cold War agenda (as I saw it) of discrediting the Soviet Union rather than understanding it. But that didn’t stop me getting my own kicks as a scholar from finding out what the Soviets didn’t want me to know. Best of all was to find out something the Soviets didn’t want me to know and Western Cold Warriors didn’t want to hear because it complicated the simple anti-Soviet story.

After each of my returns from the Soviet Union, in 1967, 1968 and 1970, I wrote a careful final report for the British that described my archival and other researches at length, gave an unflattering characterisation of my dissertation adviser, said something about conditions of student life in the dormitory and Soviet interactions with foreign students, and omitted the part of my Soviet life connected with Igor Sats and Novyi mir. Some time later, after I had finished the dissertation and got a postdoc in London, the director of my institute, a (former?) intelligence man, invited me to lunch, an unprecedented gesture, and asked me in great detail about Igor Sats and Novyi mir. I was not sure how he knew I knew them, but perhaps British intelligence, as well as the Soviet postal censors, were reading Igor’s letters. I regarded it as a debriefing and resented it. If it was a choice between Novyi mir and British intelligence, I was on Novyi mir’s side.

But the Soviets were having none of me: I had already been outed. The denunciation was published in the Soviet daily Sovetskaia Rossiia at the end of my first year in the Soviet Union, although I didn’t know about it until I got back to Oxford. ‘He who is obliged to hide the truth’ was the heading, and the story below it attacked me and a couple of other Western scholars as bourgeois falsifiers. The offending article – my first and only scholarly publication at that time – was about Lunacharsky, noting his occasional divergences from Soviet orthodoxy. According to the story’s author, my article was an example of ‘bourgeois so-called research’ whose sole purpose was to tarnish the Soviet Union and discredit socialism. ‘The ploys of such ideological diversionaries,’ he concluded ominously, ‘are hard to distinguish from those of bourgeois spies.’

The author was ‘V. Golant, PhD in history’. Somebody later told me that Golant, while writing for the most reactionary and anti-Western paper in Moscow, was actually a quasi-dissident who subsequently emigrated to Israel. For all I know, he may privately have liked my article, or perhaps even thought it insufficiently anti-Soviet. In any case, it didn’t matter. The article was signed S. Fitzpatrick, and Golant assumed that Fitzpatrick was a man. But the person whom the British Council had sent to the Soviet Union was not a man called S. Fitzpatrick but a woman called (in Cyrillic spelling) Sh. M. Brius (Bruce). To be sure, these two people were both British scholars who seemed to be working on the same topic. But nobody made the connection between Bruce and Fitzpatrick – a typical screw-up. My cover held. The spy in the archive remained unnoticed.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.