An epiphany is beguiling Europe. Far from dwindling in historical significance, the Old World is about to assume an importance for humanity it has never, in all its days of dubious past glory, before possessed. At the end of Postwar, his 800-page account of the continent since 1945, the historian Tony Judt exclaims at ‘Europe’s emergence in the dawn of the 21st century as a paragon of the international virtues: a community of values … held up by Europeans and non-Europeans alike as an exemplar for all to emulate’.1 The reputation, he assures us, is ‘well-earned’. The same vision grips the seers of New Labour. Why Europe Will Run the 21st Century declaims the title of a manifesto by Mark Leonard, the party’s foreign policy wunderkind.2 ‘Imagine a world of peace, prosperity and democracy,’ he enjoins the reader. ‘What I am asking you to imagine is the “New European Century”.’ How will this entrancing prospect come about? ‘Europe represents a synthesis of the energy and freedom that come from liberalism with the stability and welfare that come from social democracy. As the world becomes richer and moves beyond satisfying basic needs such as hunger and health, the European way of life will become irresistible.’ Really? Absolutely. ‘As India, Brazil, South Africa and even China develop economically and express themselves politically, the European model will represent an irresistibly attractive way of enhancing their prosperity whilst protecting their security. They will join with the EU in building “a New European Century”.’

Not to be outdone, the futurologist Jeremy Rifkin – American by birth, but by any standards an honorary European: indeed a personal adviser to Romano Prodi when he was president of the European Commission – has offered his guide to The European Dream.3 Seeking ‘harmony, not hegemony’, he tells us, the EU ‘has all the right markings to claim the moral high ground on the journey towards a third stage of human consciousness. Europeans have laid out a visionary road map to a new promised land, one dedicated to reaffirming the life instinct and the Earth’s indivisibility.’ After a lyrical survey of this route – typical staging-posts: ‘Government without a Centre’, ‘Romancing the Civil Society’, ‘A Second Enlightenment’ – Rifkin, warning us against cynicism, concludes: ‘These are tumultuous times. Much of the world is going dark, leaving many human beings without clear direction. The European Dream is a beacon of light in a troubled world. It beckons us to a new age of inclusivity, diversity, quality of life, deep play, sustainability, universal human rights, the rights of nature, and peace on Earth.’

These transports may seem peculiarly Anglo-Saxon, but there is no shortage of more prosaic equivalents on the Continent. For Germany’s leading philosopher, Jürgen Habermas, Europe has found ‘exemplary solutions’ for two great issues of the age: ‘governance beyond the nation-state’ and systems of welfare that ‘serve as a model’ to the world. So why not triumph in a third? ‘If Europe has solved two problems of this magnitude, shouldn’t it issue a further challenge: to defend and promote a cosmopolitan order on the basis of international law’ – or, as his compatriot the sociologist Ulrich Beck puts it, ‘Europeanisation means creating a new politics. It means entering as a player into the meta-power game, into the struggle to form the rules of a new global order. The catchphrase for the future might be: Move over America – Europe is back!’ In France, Marcel Gauchet, theorist of democracy and an editor of Le Débat, the country’s central journal of ideas, explains, more demurely, that ‘we may be allowed to think that the formula the Europeans have pioneered is destined eventually to serve as a model for the nations of the world. That lies in its genetic programme.’

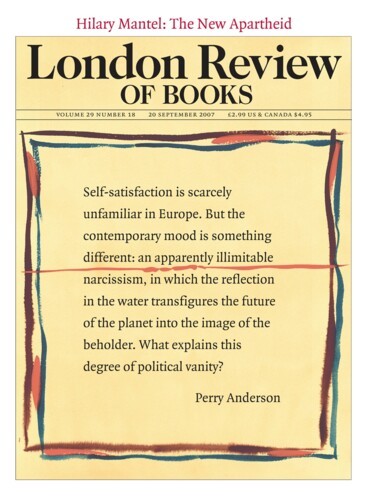

Self-satisfaction is scarcely unfamiliar in Europe. But the contemporary mood is something different: an apparently illimitable narcissism, in which the reflection in the water transfigures the future of the planet into the image of the beholder. What explains this degree of political vanity? Obviously, the landscape of the continent has altered in recent years, and its role in the world has grown. Real changes can give rise to surreal dreams, but they need to be calibrated properly, to see what the connections or lack of them might be. A decade ago, three great imponderables lay ahead: the advent of monetary union, as designed at Maastricht; the return of Germany to regional preponderance, with reunification; and the expansion of the EU into Eastern Europe. The outcome of each remained ex ante indeterminate. How far have they been clarified since?

Of its nature, the introduction of a single currency, adopted simultaneously by 11 out of 15 member states of the EU on the first day of 1999, was the most punctual and systematic transformation of the three. It was always reasonable to suppose its effects would be the soonest visible, and most clear-cut. Yet this has proved so only in the most limited technical sense, that the substitution of a dozen monies by one (Greece joined in 2002) was handled extremely smoothly, without glitch or mishap: an administrative tour de force. Otherwise, contrary to general expectations, the net upshot of the monetary union that came into force in the Eurozone eight years ago remains undecidable. The stated purpose of the single currency was to lower transaction costs and increase predictability of returns for business, so unleashing higher investment and faster growth of productivity and output.

But to date the causes have failed to generate the results. The dynamic effects of the Single European Act of 1986, held by most orthodox economists to be an initiative of greater significance than EMU, had already been wildly oversold: the official Cecchini Report estimated it would add between 4.3 and 6.4 per cent to the GDP of the Community where in reality it yielded gains of little over 1 per cent. So far, the pay-off for EMU has been even more disappointing. Far from picking up, growth in the Eurozone initially slowed down, from an average of 2.4 per cent in the five years before monetary union, to 2.1 in the first five years after it. Even with the modest acceleration of the last three years, it remains below the level of the 1980s. In 2000, on the heels of the single currency, the Lisbon summit promised to create within ten years ‘the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world’. In the event, the EU has so far recorded a growth rate well below that of the US, and has lagged far behind China. Caught between the scientific and technological magnetism of America, where two-fifths of all scientists – some 400,000 – are now EU-born, and the cheap labour of the PRC, where average wages are well over twenty times lower, Europe has not had much to show for its bombast.

Not only has the performance of the single-currency bloc been well below America’s. More pointedly, the Eurozone has been outstripped by those countries within the EU which declined to scrap their own currencies, Sweden, Britain and Denmark all posting higher rates of growth over the same period. Casting a further shadow over the legacy of Maastricht, the Stability Pact which was supposed to ensure that fiscal indiscipline at national level would not undermine monetary rigour at supranational level has been breached repeatedly and with impunity by both Germany and France, the two leading economies of the Eurozone. Had its deflationary impact been enforced, as it was on Portugal, which was in less of a position to resist, overall growth would have been yet lower.

Still, it would be premature to think that any unequivocal verdict on monetary union had been reached. The advocates of EMU point to Ireland and Spain as success stories within the Eurozone, and look to the general economic upturn of the past year, led by Germany, as a sign that monetary union may at last be coming into its own. Above all, they can vaunt the strength of the euro itself. Not only are long-term interest rates in the Eurozone below those in the US. More strikingly, the euro has overtaken the dollar as the world’s premier currency in the international bond market. One result has been to power a wave of cross-border mergers and acquisitions in Euroland itself, evidence of the kind of capital deepening the architects of monetary union envisaged. Given the volatility of relative regional or national standings in the world economy – Japan’s is only the most spectacular reversal of fortune since the 1980s – might not the Eurozone, after somewhat over seven lean years, now be poised for their biblical opposite?

Here, clearly, much depends on the degree of European interconnection with, or insulation from, the US economy, which dominates global demand. The mediocrity of Eurozone performance since 1999, attributable in the eyes of economic liberals to statist inertias and labour-market rigidities that it has taken time to overcome, but that are now giving way, has unfolded against the background of a global conjuncture, driven principally by American consumption, which for the last five years has been highly favourable – world economic growth averaging over 4.5 per cent, a rate not seen since the 1960s. A large part of this boom has come from rocketing house prices. That holds above all for the US, but also for much of the OECD: not least such once peripheral economies as Spain and Ireland, where construction has been the linchpin of recent growth. In the major Eurozone economies, on the other hand, where mortgages are not so central to financial markets, such effects have been more subdued. But, as the exposure of European banks to the collapse of sub-prime markets in the US is currently showing, the lines of repackaged credit are now so diffused and entangled across financial markets that the Eurozone is unlikely to be sheltered from a transatlantic recession.

The role of Germany in the new Europe remains no less ambiguous. Absorption of the DDR has restored the country to its standing at the beginning of the 20th century as the strategically central land of the continent, the most populous nation and the largest economy. But the longer-term consequences of reunification have still to unfold. Internationally, the Berlin republic has unquestionably become more assertive, shedding a range of postwar inhibitions. In the past decade the Luftwaffe has returned to the Balkans, Einsatztruppen are fighting in West Asia, the Deutsche Marine patrols the Eastern Mediterranean. But these have been subcontracted enterprises, in Nato or UN operations governed by the United States, not independent initiatives. Diplomatic postures have been more significant than military. Under Schröder, close ties were developed with Russia, in an entente that became the most distinctive feature of his foreign policy. But this was not a second Rapallo Pact, at the expense of western neighbours. Under Chirac and Berlusconi, France and Italy courted Putin scarcely less, but with fewer economic trumps in hand. Within Europe itself, the Red-Green government in Berlin, for all its well-advertised generational lack of complexes, never rocked the boat in the way its Christian Democrat predecessor in Bonn had done. Since 1991, in fact, there has been no action to compare with Kohl’s unilateral recognition of Slovenia, precipitating the disintegration of Yugoslavia. Merkel has moved successfully to circumvent the will of French and Dutch voters, but was in no position to accomplish this on her own: for that, governments in Paris and the Hague were necessary. The prospects of any informal German hegemony in Europe, classically considered, seem at present remote.

Part of the reason for the relatively subdued profile of the new Germany has been the cost of reunification itself, for which the bill to date has come to more than a trillion dollars, saddling the country for years with stagnation, high unemployment and mounting public debt. France, though no greyhound itself, consistently outpaced Germany, posting faster rates of growth for a full decade from 1994 to 2004, with more than double its increase in GDP in the first five years of the new century. In 2006, substantial German recovery finally arrived, and the tables have been turned. Currently the world’s leading exporter, Germany now looks as if it might be about to exercise once again something like the economic dominance of Europe it enjoyed in the days of Schmidt and the early Kohl. Then it was the tight money policies of the Bundesbank that held its neighbours by the throat. With the euro, that form of pressure has gone. What threatens to replace it is the remarkable wage repression on which German recovery has been based. Between 1998 and 2006, unit labour costs in Germany actually fell – a staggering feat: real wages declined for seven straight years – while they rose some 15 per cent in France and Britain, and between 25 and 35 per cent in Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece. With devaluation now barred, the Mediterranean countries are suffering a drastic loss of competitiveness that augurs ill for the whole southern tier of the EU. Harsher forms of German power, pulsing through the market rather than issuing from the high command or central bank, may lie in store. It is too soon to write off a regional Grossmacht.

Germany has now been reunited for 16 years. A single currency has circulated for eight years. The enlargement of the EU is just over three years old: it would be strange if its outcomes were already clearer. In practice the expansion of the EU to the East was set in motion in 1993, and completed – for the moment – only this year, with the accession of Romania and Bulgaria. At one level it is plain why it should be perhaps the principal source of satisfaction in today’s chorus of European self-congratulation. All nine former ‘captive nations’ of the Soviet bloc have been integrated without a hitch into the Union. Only the lands of a once independent Communism, in the time of Tito and Hoxha, wait to join the fold, and even there a start has been made with Slovenia. Capitalism has been restored smoothly and speedily, without vexing delays or derogations. Indeed, as the director-general of the EU Commission for Enlargement recently observed, ‘Nowadays the level of privatisation and liberalisation of the market is often higher in new member states than old ones.’ In this newly freed zone, rates of growth have also been considerably higher than in the larger economies to the west.

No less impressive has been the virtually frictionless implantation of political systems matching liberal norms – representative democracies complete with civil rights, elected parliaments, separation of powers, alternation of governments. Under the benevolent but watchful eye of the Commission, seeing to it that criteria laid down at the Copenhagen Summit of 1993 were properly met, Eastern Europe has been shepherded into the comity of free nations. There was no backsliding. The elites of the region were in most cases only too anxious to oblige. For their populations, constitutional niceties were less important than higher standards of living once the late Communist yoke was thrown off, although few if any citizens were indifferent to the humbler liberties of speech, occupation or travel. When the time for accession came, there was assent, but little enthusiasm. Only in two countries out of ten – Lithuania and Slovenia – did a majority of the electorate turn out to vote for it, in referenda which most of the population elsewhere ignored, no doubt in part because they regarded it as a fait accompli by their leaders.

Still, however technocratic or top-down the mechanics of enlargement may have been, the formal unification of the two halves of Europe is a historical achievement of the first order. This is not because it has restored the countries of the East to an age-long common home, from which only a malign fate – the totalitarian grip of Russia – wrested them after the Second World War, as the ideologues of Central Europe, Kundera and others, have argued. The division of the continent has deeper roots, and goes back much further, than the pact at Yalta. In a well-received book, the American historian Larry Wolff charged travellers and thinkers of the Enlightenment with ‘the invention of Eastern Europe’ as a supercilious myth of the 18th century.4 The reality is that from the time of the Roman Empire onwards, the lands now covered by the new member states of the Union were nearly always poorer, less literate and less urbanised than most of their counterparts to the west: prey to nomadic invasions from Asia; subjected to a second serfdom that spared neither the German lands beyond the Elbe nor even relatively advanced Bohemia; annexed by Habsburg, Romanov, Hohenzollern or Ottoman conquerors. Their fate in the Second World War and its aftermath was not an unhappy exception in their history, but – catastrophically speaking – par for the course.

It is this millennial record, of repeated humiliation and oppression, that entry into the Union offers a chance, finally, to leave behind. Who, with any sense of the history of the continent, could fail to be moved by the prospect of a cancellation in the inequality of its nations’ destinies? The original design for EU expansion to the East, a joint product of German strategy under Kohl and interested local elites, seconded by assorted Anglo-American publicists, was to fast-track Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic into the Union, as the most congenial states of the region, with the staunchest records of resistance to Communism and the most Westernised political classes, leaving less favoured societies to kick their heels in the rear. Happily, this invidious redivision of the East was avoided. Credit for preventing it must go in the first instance to France, which from the beginning advocated a ‘regatta’ approach, insisting on the inclusion of Romania, which made it difficult to exclude Bulgaria; to Sweden, which championed Estonia, with the same effect on Latvia and Lithuania; and to the Prodi Commission, which eventually rallied to comprehensive rather than selective enlargement. The result was a far more generous settlement than originally envisaged.

What of the economic upshot of expansion for the Union itself? Thanks to the modesty of the regional funds allocated to the East, the financial cost of enlargement has been significantly less than once estimated, and the balance of trade has favoured the more powerful economies of the West. This, however, is small change. The real takings – or bill, depending on who is looking at it – lie elsewhere. Core European capital now has a major pool of cheap labour at its disposal, conveniently located on its doorstep, not only dramatically lowering its production costs in plants to the East, but capable of exercising pressure on wages and conditions in the West. The archetypal case is Slovakia, where wages in the auto industry are one eighth of those in Germany, and more cars per capita are shortly going to be produced – Volkswagen and Peugeot in the lead – than in any other country in the world. It is the fear of such relocation, with the closure of factories at home, that has cowed so many German workers into accepting longer hours and less pay. Race-to-the bottom pressures are not confined to wages. The ex-Communist states have pioneered flat taxes to woo investment, and now compete with each other for the lowest possible rate: Estonia started with 26 per cent, Slovakia offers 19 per cent, Romania advertises 16 per cent, while Poland is now mooting a best-buy of 15 per cent.

The role configured by the new East in the EU, in other words, promises to be something like that played by the new South in the American economy since the 1970s: a zone of business-friendly fiscal regimes, weak or non-existent labour movements, low wages and – therefore – high investment, registering faster growth than in the older core regions of continent-wide capital. Like the US South, too, the region seems likely to fall somewhat short of the standards of political respectability expected in the rest of the Union. Already, now that they are safely inside the EU and there is no longer the same need to be on their best behaviour, the elites of the region show signs of kicking over the traces. In Poland, the ruling twins defy every norm of ideological correctness as understood in Strasbourg or Brussels. In Hungary, riot police stand on guard around a ruler unabashed at vaunting his lies to voters. In the Czech Republic, months pass without parliament being able to form a government. In Romania, the president insults the prime minister in a phone-in call to a television talk-show. But, as in Kentucky or Alabama, such provincial quirks add a touch of folkloric colour to the drab metropolitan scene more than they disturb it.

All analogies have their limits. The distinctive role of the new South in the political economy of the US has depended in part on immigration attracted by the region’s climate, which has given it rates of demographic growth well above the national average. Eastern Europe is much more likely to suffer out-migration, as the recent tide of Poles arriving in Britain, and similar numbers from the Baltics and elsewhere in Ireland and Sweden, suggest. But labour mobility in any direction is – and, for obvious linguistic and cultural reasons, will remain – far lower in the EU than in the US. Local welfare systems, inherited from the Communist past, and not yet greatly dismantled, are also potential constraints on a Southern path. Nor does the East, with less than a quarter of the population of the Union, have anything like the relative weight of the South in the United States, not to speak of the political leverage of the region at federal level. For the moment, the effect of enlargement has essentially been much what the Foreign Office and the employers’ lobbies in Brussels always hoped it would be: the distension of the EU into a vast free-trade zone, with a newly acquired periphery of cheap labour.

The integration of the East into the Union is the major achievement to which admirers of the new Europe can legitimately point. Of course, as with the standard encomia of the record of EU as a whole, there is a gap between ideology and reality in the claims made for it. The Community that became a Union was never responsible for the ‘fifty years of peace’ conventionally ascribed to it, a piety attributing to Brussels what in any strict sense belonged to Washington. When actual wars threatened in Yugoslavia, far from preventing their outbreak, the Union if anything helped to trigger them. In not dissimilar fashion, publicists for the EU often imply that without enlargement Eastern Europe would never have reached the safe harbour of democracy, foundering in new forms of totalitarianism or barbarism. There is somewhat more substance to this argument, since the EU has supervised stabilisation of the political systems of the region. But this claim too exaggerates dangers in the service of vanities. The EU played no role in the overthrow of the regimes installed by Stalin, and there is little sign that any of the countries in which they fell were at risk of lapsing into new dictatorships, were it not for the saving hand of the Commission. Enlargement has been a sufficient historical annealment, and so far economic success, not to require claims that it has also been, counter-factually, a political deliverance. The standard hype demeans rather than elevates what has been achieved.

There remains the largest question of all. What has been the impact of expansion to the East on the institutional framework of the EU itself? Here the glass darkens. For if enlargement has been the principal achievement of the recent period, the constitution that was supposed to renovate the Union has been its most signal failure, and the potential interactions between the two remain a matter of obscurity. The Convention on the Future of Europe met in early 2002, and in mid-2003 delivered a draft European Constitution that was agreed by the European Council in the summer of 2004. Delegates from candidate countries were nominally included in the Convention, but since the Convention itself amounted to little more than window-dressing for the labours of its president, Giscard d’Estaing, assisted by a British factotum, John Kerr, the two real authors of the draft, their presence was of no consequence. The future charter of Europe was written for the establishments of the West, the governments of the existing 15 member states who had to approve it, relegating the countries of the East to onlookers. In effect, the logic of a constituent will was inverted: instead of enlargement becoming the common basis of a new framework, the framework was erected before enlargement.

The ensuing debacle came as a brief thunderclap to the Western elites. The Constitution – more than 500 pages long, comprising 446 articles and 36 supplementary protocols, a bureaucratic elephantiasis without precedent – increased the power of the four largest states in the Union, Germany, France, Britain and Italy; topped the inter-governmental complex in which they would have greater sway with a five-year presidency, unelected by the European Parliament, let alone the citizens of the Union; and inscribed the imperatives of a ‘highly competitive’ market, ‘free of distortions’, as a foundational principle of political law, beyond the reach of popular choice. The founders of the American Republic would have rubbed their eyes in disbelief at such a ponderous and rickety construction. But so overwhelming was the consensus of the continent’s media and political class behind it, that few doubted it would come into force. To the astonishment of their rulers, however, voters made short work of it. In France, where the government was unwise enough to dispatch copies of the document to every voter (Giscard complained of this folly with his handiwork), little was left of it at the end of a referendum campaign in which a spirited popular opposition – without the support of a single mainstream party, newspaper, magazine, let alone radio or television programme – routed an establishment united in endorsing it. Rarely, even in recent French history, was a pensée quite so unique upended so spectacularly.

In the last days of the campaign, as polls showed increasing rejection of the Constitution among voters, panic gripped the French media. But no local hysterics, though there were many, rivalled those in Germany. ‘Europe Demands Courage,’ admonished Günter Grass, Jürgen Habermas and a cohort of like-minded German intellectuals, in an open letter dispatched to Le Monde. Warning their neighbours that ‘France … would isolate itself fatally if it were to vote “No”,’ they went on: ‘The consequences of a rejection would be catastrophic,’ indeed ‘an invitation to suicide’, for ‘without courage there is no survival.’ In member states new and old ‘the Constitution fulfils a dream of centuries,’ and to vote for it was not just a duty to the living, but to the dead: ‘we owe this to the millions upon millions of victims of our lunatic wars and criminal dictatorships.’ This from a country where no risk was taken of any democratic consultation of the elector -ate, and pro forma ratification of the Constitution was stage-managed in the Bundesrat to impress French voters a few days before their referendum, with Giscard as guest of honour at the podium. As for French isolation, three days later the Dutch – told, still more bluntly, that Auschwitz awaited Europe if they failed to vote yes – threw out the Constitution by an even wider margin.

Such popular repudiation of the charter for a new Europe, not because it was too federalist, but because it seemed to be little more than an impenetrable scheme for the redistribution of oligarchic power, embodying everything most distrusted in the arrogant, opaque system the EU appeared to have become, was not in reality a bolt from the blue. Virtually every time – there have not been many – that voters have been allowed to express an opinion about the direction the Union was taking, they have rejected it. The Norwegians refused the EC tout court; the Danes declined Maastricht; the Irish, the Treaty of Nice; the Swedes, the euro. Each time, the political class promptly sent them back to the polls to correct their mistake, or waited for the occasion to reverse the verdict. The operative maxim of the EU has become Brecht’s dictum: in case of setback, the government should dissolve the people and elect a new one.

Predictably, amid the celebrations of the 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome that gave birth to the EEC, European heads of state were soon discussing how to cashier the popular will once again, and reimpose the Constitution with cosmetic alterations but without exposing it this time to the risks of a democratic decision. At the Brussels summit this June, the requisite adjustment – now renamed a simple treaty – was agreed. To let it disavow a referendum, Britain was exempted from the Charter of Fundamental Rights to which all other member states subscribed. To throw a sop to French opinion, references to unfettered competition were tucked away in a protocol, rather than appearing in the main document. To square the conscience of the Dutch, ‘promotion of European values’ was made a test of membership. To save the face of Poland’s rulers, the demotion of their country to second rank in the Council was deferred for a decade, leaving their successors to come to terms with it.

The principal novelty at this gathering to resuscitate what French and Dutch voters had buried was the determination of Germany to ensure its primacy in the electoral structure of the Council. Polish objections to a formula doubling Germany’s weight, and drastically reducing Poland’s, had – for reasons that voting theory in international organisations has long made clear, as experts in such matters pointed out – every technical consideration of fairness on their side. But issues of equity were of no more relevance to the outcome than issues of democracy. After blustering that demographic losses in the Second World War entitled Poland to proportionate compensation in the design of the Union, the Kaczynski twins crumpled as quickly as the country’s prewar colonels before the German blitz. Brave talk forgotten, it was all over in a phone call. For the region where Poland accounts for nearly half the population and GDP, the episode is a lesson in the tacit hierarchy of states it has entered. The East is welcome, but should not get above itself.

Not that crumbs are unavailable. As the British, Dutch and French rulers, so the Polish too received, with their postponed demotion, the fig-leaf needed to dispense them from submitting the reanimated Constitution to the opinion of their voters. It was left to Ireland’s Premier Ahern – along with Blair, another of the conference’s recent escapees from a cloud of corruption – to exclaim, in a moment of unguarded delight: ‘90 per cent of it is still there!’ Even loyal commentators have found it difficult to suppress all disgust at the cynicism of this latest exercise in the ‘Community method’. The contrast between such realities and the placards of the touts for the new Europe could scarcely be starker. The truth is that the light of the world, role model for humanity at large, cannot even count on the consent of its populations at home.

What kind of political order, then, is taking shape in Europe, 15 years after Maastricht? The pioneers of European integration – Monnet and his fellow spirits – envisaged the eventual creation of a federal union that would one day be the supranational equivalent of the nation-states out of which it emerged, anchored in an expanded popular sovereignty, based on universal suffrage, its executive answerable to an elected legislature, and its economy subject to requirements of social responsibility. In short, a democracy magnified to semi-continental scale (they had only Western Europe in mind). But there was always another way of looking at European unification, which saw it more as a limited pooling of powers by member governments for certain – principally economic – ends, that did not imply any fundamental derogation of national sovereignty as traditionally understood, but rather the creation of a novel institutional framework for a specified range of transactions. De Gaulle famously represented one version of this outlook; Thatcher another. Between these federalist and inter-governmentalist visions of Europe, there has been a continual tension down to the present.

What has come into being, however, corresponds to neither. Constitutionally, the EU is a caricature of a democratic federation, since its Parliament lacks powers of initiative, contains no parties with any existence at European level, and wants even a modicum of popular credibility. Modest increments in its rights have not only failed to increase public interest in this body, but have been accompanied by a further decline in it. Participation in European elections has sunk steadily, to below 50 per cent, and the newest voters are the most indifferent of all. In the East, the regional figure in 2004 was scarcely more than 30 per cent; in Slovakia less than 17 per cent of voters cast a ballot for their delegates to Strasbourg. Such ennui is not irrational. The European Parliament is a Merovingian legislature. The mayor in the palace is the Council of Ministers, where real law-making decisions are taken, topped by the European Council of the heads of state, meeting every three months. Yet this complex in turn fails the opposite logic of an inter-governmental authority, since it is the Commission – the EU’s unelected executive – alone that can propose the laws on which the Council and (more notionally) the Parliament deliberate. The violation of a constitutional separation of powers in this dual authority – a bureaucracy vested with a monopoly of legislative initiative – is flagrant. Alongside this hybrid executive, moreover, is an independent judiciary, the European Court, capable of rulings discomfiting any national government.

At the centre of this maze lies the impenetrable zone in which the rival law-making instances of the Council and the Commission interlock, more obscure than any other feature of the Union: the nexus of ‘Coreper’ committees in Brussels,5 where emissaries of the former confer behind closed doors with functionaries of the latter, to generate the avalanche of legally binding directives that form the main output of the EU – close on 100,000 pages to date. Here is the effective point of concentration of everything summed up in the phrase – smacking, characteristically, of the counting-house rather than the forum – ‘democratic deficit’, one ritually deplored by EU officials themselves. In fact, what the trinity of Council, Coreper and Commission figures is not just an absence of democracy – it is certainly also that – but an attenuation of politics of any kind, as ordinarily understood. The effect of this axis is to short-circuit – above all at the critical Coreper level – national legislatures that are continually confronted with a mass of decisions over which they lack any oversight, without affording any supranational accountability in compensation, given the shadow-play of the Parliament. The farce of popular consultations that are regularly ignored is only the most dramatic expression of this oligarchic structure, which sums up the rest.

Alongside their negation of democratic principles, two further and less familiar features of these arrangements stand out. The vast majority of the decisions of the Council, Commission and Coreper concern domestic issues that were traditionally debated in national legislatures. But in the conclaves at Brussels these become the object of diplomatic negotiations: that is, of the kind of treatment classically reserved for foreign or military affairs, where parliamentary controls are usually weak to non-existent, and executive discretion more or less untrammelled. Since the Renaissance, secrecy has always been the other name of diplomacy. What the core structures of the EU effectively do is convert the open agenda of parliaments into the closed world of chancelleries. But even this is not all of it. Traditional diplomacy typically required stealth and surprise for success. But it did not preclude discord or rupture. Classically, it involved a war of manoeuvre between parties capable of breaking as well as making alliances; sudden shifts in the terrain of negotiations; alterations of means and objectives: in short, politics conducted between states, as distinct from within them, but politics nonetheless. In the disinfected universe of the EU, this all but disappears, as unanimity becomes virtually de rigueur on all significant occasions, any public disagreement, let alone refusal to accept a prefabricated consensus, increasingly being treated as if it were an unthinkable breach of etiquette. The deadly conformism of EU summits, smugly celebrated by theorists of ‘consociational democracy’, as if this were anything other than a cartel of self-protective elites, closes the coffin of even real diplomacy, covering it with wreaths of bureaucratic piety. Nothing is left to move the popular will, as democratic participation and political imagination are each snuffed out.

These structures have been some time in the making. Unreformed, they could not but be reinforced by enlargement. The distance between rulers and ruled, already wide enough in a Community of nine or 12 countries, can only widen much further in a Union of 27 or more, where economic and social circumstances differ so vastly that the Gini coefficient in the EU is now higher than in the US, the fabled land of inequality itself. It was always the calculation of adversaries of European federalism, successive British governments at their head, that the more extended the Community became, the less chance there was of any deepening of its institutions in a democratic direction, for the more impractical any conception of popular sovereignty in a supranational union would become. Their intentions have come to pass. Stretched to nearly 500 million citizens, the EU of today is in no position to recall the dreams of Monnet.

So what? There is no shortage of apologists prepared to explain that it is not just wrong to complain of a lack of democracy in the Union, conventionally understood, but that this is actually its greatest virtue. The standard argument, to be found in journals such as Prospect, goes like this. The EU deals essentially with the technical and administrative issues – market competition, product specification, consumer protection and the like – posed by the aim of the Treaty of Rome to assure the free movement of goods, persons and capital within its borders. These are matters in which voters have little interest, rightly taking the view that they are best handled by appropriate experts, rather than incompetent parliamentarians. Just as the police, fire brigade or officer corps are not elected, but enjoy the widest public trust, so it is – at any rate tacitly – with the functionaries in Brussels. The democratic deficit is a myth, because matters which voters do care strongly about – pre-eminently taxes and social services, the real stuff of politics – continue to be decided, not at Union but at national level, by traditional electoral mechanisms. So long as the separation between the two arenas and their respective types of decision is respected, and we are spared demagogic exercises in populism – putting issues that the masses cannot understand, and that should never be on a ballot in the first place, to referenda – democracy remains intact, indeed enhanced. Considered soberly, all is for the best in the best of all possible Europes.

In an unreflective sense, this case might seem to appeal to a common immediate experience of the Union. If asked in what ways they have personally been affected by the EU, most of its citizens – at least those who live in the Eurozone and Schengen belt – would certainly not mention its technical directives; they would probably answer that travel has been simplified by the disappearance of border controls and the need to change currencies. Beyond such conveniences, a narrow stratum of professionals and executives, and a somewhat broader flow of migrant workers and craftsmen, have benefited from occupational mobility across borders, though this is still quite limited: less than 2 per cent of the population of the Union lives outside its country of origin. In some ways more significant may be the programmes that take growing numbers of students to courses in other societies of the EU. Journeys, studies, a scattering of jobs: agreeable changes all, not vital issues. It is this expanse of mild amenities that no doubt explains the passivity of voters towards rulers who ignore their expressions of opinion. For nearly as striking as the repeated popular rejection of official schemes for the Union is the lack of reaction to subsequent flouting of the popular decision. The elites do not persuade the masses; but, to all appearances, they have little to fear from them.

Why then is there such persistent distrust of Brussels, if so little of what it does impinges on ordinary life, and that quite pleasantly? Subjectively, the answer is clear. There are few citizens who are not banally alienated from the way they are governed at home – virtually every poll shows how little they believe in what their rulers say, and how powerless they feel to alter what they do. Yet these are still societies in which elections are regularly held, and governments that become too disliked can be evicted. No one doubts that democracy, in this minimal sense, obtains. At European level, however, there is all too obviously not even this vestige of accountability: the grounds for alienation are cubed. If the EU really had zero impact on what voters care about, their distrust could be dismissed as a mere abstract prejudice. But in fact the intuition behind it is accurate. Since the Treaty of Maastricht, the Union has not by any means been confined to regulatory issues of scant interest to the population at large. It now has a Central Bank, without even the commitment of the Federal Reserve to sustain employment, let alone its duties to report to Congress, that sets interest rates for the whole Eurozone, backed by a Stability Pact that requires national governments to meet hard budgetary targets. In other words, determination of macroeconomic policy at the highest level has shifted upwards from national capitals to Frankfurt and Brussels. What this means is that just those issues that voters usually feel most strongly about – jobs, taxes and social services – fall squarely under the guillotines of the Bank and the Commission. The history of the past years has shown that this is not an academic matter. It was pressure from Brussels to cut public spending which led Juppé’s government to introduce the fiscal package that detonated the great French strike-wave of the winter of 1995, and brought him down. It was the corset of the Stability Pact that forced Portugal into slashing social benefits and plunging the country into a steep recession in 2003. The government in Lisbon did not survive either. The notion that today’s EU comprises little more than a set of innocuous technical rules, as value-neutral as traffic lights, is a fatuity.

There was from the beginning a third vision of what European integration should mean, distinct from either federalist or inter-governmentalist conceptions of the Community. Its far-sighted theorist was Hayek, who even before the Second World War had envisaged a constitutional structure raised sufficiently high above the nations composing it to exclude the danger of any popular sovereignty below impinging on it. In the nation-state, electorates were perpetually subject to dirigiste and redistributive temptations, encroaching on the rights of property in the name of democracy. But once heterogeneous populations were assembled in an inter-state federation, as he called it, they would not be able to re-create the united will that was prone to such ruinous interventions. Under an impartial authority, beyond the reach of political ignorance or envy, the spontaneous order of a market economy could finally unfold without interference.

By 1950, when Monnet was devising the Schuman Plan that yielded the initial European Coal and Steel Community, Hayek himself was in America, and played little part in shaping arguments for integration. Later, rejecting the idea of a single currency as statist (he favoured competing private issues), he would come to the conclusion that the Community itself remained all too dirigiste. But in Germany there was a school of theorists that saw the possibilities of European unity in much the same terms as he had originally envisaged, the Ordo-liberals of Freiburg, whose leading thinkers were Walter Eucken, Wilhelm Röpke and Alfred Müller-Armack. Lacking Hayek’s intransigent radicalism, they were close to Ludwig Erhard, the reputed architect of the postwar German miracle, and thereby had more real influence in the early days of the Common Market. But for thirty years, this was still a recessive strain in the make-up of the Community, latent but never the most salient in its development.

With the abrupt deterioration in the global economic climate in the 1970s, and the general neo-liberal turn that followed in the 1980s, Hayekian doctrine was rediscovered throughout the West. The leading edge of the change came in the UK and US, with the arrival of Thatcher and Reagan. Continental Europe never produced comparably radical regimes, but the ideological atmosphere shifted steadily in the same direction. The collapse of the Soviet bloc sealed the transformation of working assumptions. By the 1990s, the Commission was openly committed to privatisation as a principle, pressed without embarrassment on candidate countries along with other democratic niceties. Its most powerful arm had become the Competition Directorate, striking out at public sector monopolies in Western and Eastern Europe alike. In Frankfurt the Central Bank conformed perfectly with Hayek’s prewar prescriptions. What was originally the least prominent strand in the weave of European integration had become the dominant pattern. Federalism stymied, inter-governmentalism corroded, what had emerged was neither the rudiments of a European democracy controlled by its citizens, nor the formation of a European directory guided by its powers, but a vast zone of increasingly unbound market exchange, much closer to a European ‘catallaxy’ as Hayek had conceived it.

The mutation is by no means complete. The European Parliament is still there, as a memento of federal hopes foregone. Agricultural and regional subsidies, legacies of a cameralist past, continue to absorb most of the EU budget. Services, over two-thirds of Union GDP, have yet to be fully liberalised. But of a ‘social Europe’, in the sense intended by either Monnet or Delors, there is as little left as a democratic Europe. At national level, welfare regimes that distinguish the Old World from the New persist. With the exception of Ireland, the share of state expenditure in GDP remains higher in Western Europe than in the United States, and the larger part of an academic industry – the ‘varieties of capitalism literature’ – is dedicated to showing how much more caring ours, above all the Scandinavian versions, are than theirs. The claim is valid enough; the self-satisfaction less so. For as the numbers of long-term jobless and pensioners have risen, the drift of the age has been away from earlier norms of provision, not beyond them. The very term ‘reform’ now means, virtually always, the opposite of what it denoted fifty years ago: not the creation but the contraction of welfare arrangements once prized by their recipients. The only two structural advances beyond the postwar gains of social democracy – the Meidner plan for pension funds in Sweden, and the 35-hour week in France – have both been rolled back. The tide is moving in the other direction.

Today’s EU, with its pinched spending (just over 1 per cent of Union GDP), minuscule bureaucracy (around 16,000 officials, excluding translators), absence of independent taxation, and lack of any means of administrative enforcement, could in many ways be regarded as a ne plus ultra of the minimal state, beyond the most drastic imaginings of classical liberalism: less even than the dream of a nightwatchman. Its structure not only rules out a transfer, of the sort once envisaged by Delors, of social functions from national to supranational level, to counterbalance the strain these have come under from high rates of unemployment and growing numbers of pensioners. Its effect is to increase, rather than compensate for, pressure on national systems of social provision, as so many impediments to the free movement of factors of production. As a leading authority, Andrew Moravcsik, explains, ‘the neo-liberal bias of the EU, if it exists, is justified by the social welfare bias of current national policies,’ which ‘no responsible analyst believes can be maintained’ – ‘European social policy exists only in the dreams of disgruntled socialists.’ The salutary truth is that ‘the EU is overwhelmingly about the promotion of free markets. Its primary interest group support comes from multinational firms, not least US ones.’ In short: regnant in this Union is not democracy, and not welfare, but capital. ‘The EU is basically about business.’

That may be so, enthusiasts might reply, but why should it detract from the larger good that the EU represents in the world, a political community that stands alone in its respect for human rights, international law, aid to the poor of the earth, and protection of the environment? Could the Union not be described as the realisation of the Enlightenment vision of the virtues of le doux commerce, that ‘cure for the most destructive prejudices’, as Montesquieu described it, pacifying relations between states in a spirit of mutual benefit and the rule of law?

In the current repertoire of tributes to Europe, it is this claim – the unique role and prestige of the EU on the world’s stage – that now has pride of place. What it rests on, ubiquitously, is a contrast with the United States. America figures as the increasingly ominous, violent, swaggering Other of a humane continent of peace and progress: a society that is a law to itself, where Europe strives for a legal order binding on all. The values of the two, Habermas and many fellow thinkers explain, have diverged: widespread gun culture, extreme economic inequality, fundamentalist religion and capital punishment, not to speak of national bravado, divide the US from the EU and foster a more regressive conception of international relations. Reversing Goethe’s dictum, we have it better here.

The crystallisation of these images came with the invasion of Iraq. The mass demonstrations against the war of 15 February 2003, Habermas thought, might go down in history as ‘a signal for the birth of a European public’. Even such an unlikely figure as Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the probable incoming director of the IMF, announced that they marked the birth of a European nation. But if this was a Declaration of Independence, was the term ‘nation’ appropriate for what was being born? While divergence with America over the Middle East could serve as a negative definition of the emergent Europe, there was a positive side that pointed in another conceptual direction. Enlargement was the great new achievement of the Union. How should it be theorised? In late 1991, a few months after the collapse of the Soviet Union and a few days after the summit at Maastricht, J.G.A. Pocock published a prophetic essay in these pages.6 A trenchant critic of the EU, which he has always seen as involving a surrender of sovereignty and identity – and with them the conditions also of democracy – to the market, though a surrender never yet completed, Pocock observed that Europe now faced the problem of determining its frontiers, as ‘once again an empire in the sense of a civilised and stabilised zone which must decide whether to extend or refuse its political power over violent and unstable cultures along its borders’.

At the time, this was not a formulation welcome in official discourse on Europe. A decade later, the term it loosed with irony has become a common coin of complacency. As the countdown to Iraq proceeded, the British diplomat Robert Cooper, special adviser on security to Blair, and later to Prodi as head of the Commission, explained the merits of empire to readers of Prospect. ‘A system in which the strong protect the weak, in which the efficient and well-governed export stability and liberty, in which the world is open for investment and growth – all of these seem eminently desirable.’ Of course, ‘in a world of human rights and bourgeois values, a new imperialism will … have to be very different from the old.’ It would be a ‘voluntary imperialism’, of the sort admirably displayed by the EU in the Balkans. Enlargement ahead, he concluded, the Union was en route to the ‘noble dream’ of a ‘co-operative empire’. Enlargement in the bag, the Polish theorist Jan Zielonka, now at Oxford, exults in his book Europe as Empire that its ‘design was truly imperialist’: ‘power politics at its best, even though the term “power” was never mentioned in the official enlargement discourse’ – this was a ‘benign empire in action’.7

In more tough-minded style, the German strategist Herfried Münkler, holder of the chair of political theory at Humboldt University in Berlin, has expounded the world-historical logic of empires in an ambitious comparative work, Imperien, whose ideas were first presented as an aide-mémoire to a conference of ambassadors called by his country’s Foreign Ministry.8 Its theme is that, from ancient to modern times, imperial power has been required to stabilise adjacent power vacuums or turbulent border zones, holding barbarians or terrorists at bay. While naturally loyal to the West, Münkler disavows normative considerations. Human rights messianism is a moral luxury even the American empire can ill-afford. Europe, for its part, should take the measure of its emergent role as a ‘sub-imperial system’, with its own marches to control, matching its tasks to its capabilities without excessive professions of uplifting intent.

The prefix poses the question that is the crux of the new identity Europe has awarded itself. How independent of the United States is it? The answer is cruel, as even a cursory glance at the record shows. Perhaps at no time since 1950 has it been less so. The history of enlargement, the Union’s major achievement – extending the frontiers of freedom, or ascending to the rank of empire, or both at once, as the claim may be – is an index. Expansion to the East was piloted by Washington: in every case, the former Soviet satellites were incorporated into Nato, under US command, before they were admitted to the EU. Poland and the Czech Republic had joined Nato in 1999, five years before entry into the Union; Bulgaria and Romania in 2004, three years before entry; even Slovakia, Slovenia and the Baltics, a gratuitous month – just to rub in the symbolic point? – before entry (planning for the Baltics started in 1998). Croatia, Macedonia and Albania are next in line.

The expansion of Nato to former Soviet borders, casting aside undertakings given to Gorbachev at the end of the Cold War, was the work of the Clinton administration. Twelve days after the first levy of Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic had joined the Alliance, the Balkan War was launched – the first full-scale military offensive in Nato’s history. The successful blitz was an American operation, with token auxiliaries from Europe, and virtually no dissent in public opinion. These were harmonious days in Euro-American relations. There was no race between the EU and Nato in the East. Brussels deferred to the priority of Washington, which encouraged and prompted the advance of Brussels. So natural has this asymmetrical symbiosis now become that the United States can openly specify what further states should join the Union. When Bush told European leaders in Ankara, at a gathering of Nato, that Turkey must be admitted into the EU, Chirac was heard to grumble that the US would not like being instructed by Europeans to welcome Mexico into the federation; but when the European Council met to decide whether to open accession negotiations with Turkey, Rice telephoned the assembled leaders from Washington to ensure the right outcome, without hearing any inappropriate complaints from them about sovereignty. At this level, friction between Europe and America remains minimal.

Why then has there been that sense of a general crisis in transatlantic relations, which has given rise to such an extensive literature? In the EU, media and public opinion are at one in holding the conduct of the Republican administration outside Nato to be essentially responsible. Scanting the Kyoto protocols and the International Criminal Court, sidelining the UN, trampling on the Geneva Conventions, and stampeding into the Middle East, the Bush regime has on this view exposed a darker side of the United States, that has understandably been met with near universal abhorrence in Europe, even if etiquette has restrained expressions of it at diplomatic level. Above all, revulsion at the war in Iraq has, more than any other single episode since 1945, led to the rift recorded in the painful title of Habermas’s latest work, The Divided West.9

In this vision, there is a sharp contrast between the Clinton and Bush presidencies, and it is the break in the continuity of American foreign policy – the jettisoning of consensual leadership for an arrogant unilateralism – that has alienated Europeans. There is no question of the intensity of this perception. But in the orchestrations of America’s Weltpolitik, style is easily mistaken for substance. The brusque manners of the Bush administration, its impatience with the euphemisms of the ‘international community’ and blunt rejection of Kyoto and the ICC, offended European sensibilities from the start. Clinton’s emollient gestures were more tactful, if in practice their upshot – neither Kyoto nor the ICC ever risked passage into law while he was in office – was often much the same. More fundamentally, as political operations, a straight line led from the war in the Balkans to the war in Mesopotamia. In both, a casus belli – imminent genocide, imminent nuclear weapons – was trumped up; the Security Council ignored; international law set aside; and an assault unleashed.

United over Yugoslavia, Europe split over Iraq, where the strategic risks were higher. But the extent of European opposition to the march on Baghdad was always something of an illusion. On the streets, in Italy, Spain, Germany, Britain, huge numbers of people demonstrated against the invasion. Opinion polls showed majorities against it everywhere. But once it had occurred, there was little protest against the occupation, let alone support for the resistance to it. Most European governments – Britain, Spain, Italy, Netherlands, Denmark, Portugal in the West; all in the East – backed the invasion, and sent troops to bulk up the US forces holding the country down. Out of the 12 member states of the EU in 2003, just three – France, Germany and Belgium – came out against the prospect of war before the event. None condemned the attack when it was launched. But the declared opposition of Paris and Berlin to the plans of Washington and London gave popular sentiment across Europe a point of concentration, confirming and amplifying its sense of distance from power and opinion in America. The notion of an incipient Declaration of Independence by the Old World was born here.

Realities were rather different. Chirac and Schröder had a domestic interest in countering the invasion. Each judged his electorate well, and gained substantially – Schröder securing re-election – from his stance. On the other hand, American will was not to be trifled with. So each compensated in deeds for what he proclaimed in words, opposing the war in public, while colluding with it sub rosa. Behind closed doors in Washington, France’s ambassador Jean-David Levitte – currently Sarkozy’s diplomatic adviser – gave the White House a green light for the war, provided it was on the basis of the first generic UN Resolution 1441, as Cheney wanted, without returning to the Security Council for the second explicit authorisation to attack that Blair wanted, which would force France to veto it. In ciphers from Baghdad, German intelligence agents provided the Pentagon with targets and co-ordinates for the first US missiles to hit the city, in the downpour of Shock and Awe. Once the ground war began, France provided airspace for USAF missions to Iraq (which Chirac had denied Reagan’s bombing of Libya), and Germany a key transport hub for the campaign. Both countries voted for the UN resolution ratifying the US occupation of Iraq, and lost no time recognising the client regime patched together by Washington.

As for the EU, its choice of a new president of the Commission in 2004 could not have been more symbolic: the Portuguese ruler who hosted Bush, Blair and Aznar at the summit in the Azores on 16 March 2003 that issued the ultimatum for the assault on Iraq. Barroso is in good company. France now has a foreign minister, Bernard Kouchner, who had no time for even the modest duplicities of his country about America’s war, welcoming it as another example of the droit d’ingérence he had always championed. Sweden, where once a prime minister could take a sharper distance from the war in Vietnam than De Gaulle himself, has a new minister for foreign affairs to match his colleague in Paris: Carl Bildt, a founder member of the Committee for the Liberation of Iraq, along with Richard Perle, William Kristol, Newt Gingrich and others. In the UK, the local counterpart has proudly restated his support for the war, though here, no doubt, the corpses were stepped over in pursuit of preferment rather than principle. Spaniards and Italians may have withdrawn their troops from Iraq, but no European government has any policy towards a society America has destroyed that is distinct from the outlook in Washington.

For the rest, Europe remains engaged to the hilt in the war in Afghanistan, where a contemporary version of the expeditionary force dispatched to crush the Boxer Rebellion has killed more civilians this year than the guerrillas it seeks to root out. The Pentagon did not require the services of Nato for its lightning overthrow of the Taliban, though British and French jets put in a nominal appearance. Occupation of the country, which has a larger population and more forbidding terrain than Iraq, was another matter, and a Nato force of five thousand was assembled to hold the fort around Kabul, while US forces finished off Mullah Omar and Bin Laden. Five years later, Omar and Osama remain at large; the West’s puppet ruler, Karzai, cannot move without a squad of mercenaries from DynCorp International to protect him; production of opium has increased tenfold; the Afghan resistance has become steadily more effective; and Nato-led forces – now comprising contingents from 37 nations, from Britain, Germany, France, Italy, Turkey, Poland down to such minnows as Iceland – have swollen to 35,000, alongside 25,000 US troops. Indiscriminate bombing, random shooting and ‘human rights abuses’, in the polite phrase, have become commonplaces of the counter-insurgency.

In the wider Middle East, the scene is the same. Europe is joined at the hip with the US, wherever the legacies of imperial control or settler zeal are at stake. Britain and France, original suppliers of heavy water and uranium for the large Israeli nuclear arsenal, which they pretend does not exist, demand along with America that Iran abandon programmes it is allowed even by the Non-Proliferation Treaty, under menace of sanctions and war. In Lebanon, the EU and the US prop up a cabinet that would not last a day if a census were called, while German, French and Italian troops provide border guards for Israel. As for Palestine, the EU showed no more hesitation than the US in plunging the population into misery, cutting off all aid when voters elected the wrong government, on the pretext that it must first recognise the Israeli state, as if Israel had ever recognised a Palestinian state, and renounce terrorism (read: any armed resistance to a military occupation that has lasted forty years without Europe lifting a finger against it). Funds now flow again, to protect a remnant valet in the West Bank.

Lovers of Europe might reply that some of this record may be questionable, but these are external issues that can scarcely be said to affect the example Europe sets the world of respect for human rights and the rule of law within its own borders. The performance of the EU or its member states may not be irreproachable in the Middle East, but isn’t the moral leadership represented by its standards at home what really counts, internationally? So good a conscience comes too easily. The war on terror knows no frontiers and the crimes committed in its name have stalked freely across the continent, in the full cognisance of its rulers. Originally, the subcontracting of torture – ‘rendition’, or the handing over of a victim to the attentions of the secret police in client states – was, like so much else, an invention of the Clinton administration, which introduced the practice in the mid-1990s. Asked about it a decade later, the CIA official in charge of the programme, Michael Scheuer, simply said: ‘I check my moral qualms at the door.’ As one would expect, it was Britain that collaborated with the first renditions, in the company of Croatia and Albania.

Under the Bush administration, the programme expanded. Three weeks after 9/11, Nato declared that Article V of its charter, mandating collective defence in the event of an attack on one of its members, was activated. By then American plans for the descent on Afghanistan were well advanced, but they did not include European participation in Operation Enduring Freedom; the US high command had found the need for consultation in a joint campaign cumbersome in the Balkan War, and did not want to repeat the experience. Instead, at a meeting in Brussels on 4 October 2001, the allies were called on for other services. The specification of these remains secret, but as the second report to the Council of Europe – released in June this year – by the courageous Swiss investigator Dick Marty, has shown, a stepped-up programme of renditions must have been high on the list. Once Afghanistan was taken, Baghram airbase outside Kabul became both interrogation centre for the CIA and loading-bay for prisoners to Guantánamo. The traffic was soon two-way, and its pivot was Europe. In one direction, captives were transported from Afghan or Pakistani dungeons to Europe, either to be held there in secret CIA jails, or shipped onwards to Cuba. In the other direction, captives were flown from secret locations in Europe for requisite treatment in Afghanistan.

Though Nato initiated this system, the abductions it involved were not confined to members of the North Atlantic Council. Europe was eager to help America, whether or not fine print obliged it to do so. North, south, east and west: no part of the continent failed to join in. New Labour’s contribution occasions no surprise: with up to 650,000 civilians dead from the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq, it would have been unreasonable for the Straws, Becketts, Milibands to lose any sleep over the torture of the living. More striking is the role of the neutrals. Under Ahern, Ireland furnished Shannon to the CIA for so many westbound flights that locals dubbed it Guantánamo Express. Social-democratic Sweden, under its portly boss Göran Persson, now a corporate lobbyist, handed over two Egyptians seeking asylum to the CIA, who took them straight to torturers in Cairo. Under Berlusconi, Italy helped a large CIA team to kidnap another Egyptian in Milan, who was flown from the US airbase in Aviano, via Ramstein in Germany, for the same treatment in Cairo.10 Under Prodi, a government of Catholics and ex-Communists has sought to frustrate the judicial investigation of this kidnapping, while presiding over the expansion of Aviano. Switzerland proffered the overflight that took the victim to Ramstein, and protected the head of the CIA gang that seized him from arrest by the Italian judicial authorities – he now basks in Florida.

Further east, Poland did not transmit captives to their fate in the Middle East, but incarcerated them for treatment on the spot, in torture chambers constructed for ‘high-value detainees’ by the CIA at the Stare Kiejkuty intelligence base, Europe’s own Baghram – facilities unknown in the time of Jaruzelski’s martial law. In Romania, a military base north of Constanza performed the same services, under the superintendence of the country’s current president, the staunchly pro-Western Traian Basescu. In Bosnia, six Algerians were illegally seized at American behest, and flown from Tuzla – beatings in the aircraft en route – to the US base at Incirlik in Turkey, and thence to Guantánamo, where they still crouch in their cages. In Macedonia, scene of Blair’s moving encounters with refugees from Kosovo, there was a combination of the two procedures, as a German of Lebanese descent was kidnapped at the border; held, interrogated and beaten by the CIA in Skopje; then drugged and shipped to Kabul for more extended treatment. Eventually, when it became clear, after he went on hunger-strike, that his identity had been mistaken, he was flown blindfold to a Nato-upgraded airbase in Albania, and deposited back in Germany.

There the Red-Green government had been well aware of what happened to him, one of its agents interrogating him in his oubliette in Kabul – Otto Schily, the minister of the interior, was in the Afghan capital at the time – and accompanying his flight back to Albania. But it was no more concerned about his fate than about that of another of its residents, a Turk born in Germany, seized by the CIA in Pakistan and dispatched to the gulag in Guantánamo, where he too was interrogated by German agents. Both operations were under the control of today’s Social Democratic foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, then in charge of the secret services, who not only covered for the torturing of the victim in Cuba, but even declined an American offer to release him. In a letter to the man’s mother, Joschka Fischer, Green foreign minister at the time, explained that the government could do nothing for him. In ‘such a good land’, as a leading admirer has recently described it, Fischer and Steinmeier remain the most popular of politicians. The new interior minister, Wolfgang Schäuble, is more robust, publicly calling for assassination rather than rendition in dealing with deadly enemies of the state, in the Israeli manner.

Such is the record set out in the two detailed reports by Marty to the Council of Europe (nothing to do with the EU), each an exemplary document of meticulous detective work and moral passion. If this Swiss prosecutor from Ticino were representative of the continent, rather than a voice crying in the wilderness, there would be reason to be proud of it. He ends his second report by expressing the hope that his work will bring home ‘the legal and moral quagmire into which we have collectively sunk as a result of the US-led “war on terror”. Almost six years in, we seem no closer to pulling ourselves out of this quagmire.’ Indeed. Not a single European government has conceded any guilt, while all continue imperturbably to hold forth on human rights. We are in the world of Ibsen – Consul Bernick, Judge Brack and their like – updated for postmoderns. Pillars of society, pimping for torture.

What has been delivered in these practices are not just the hooded or chained bodies, but the deliverers themselves: Europe surrendered to the United States. This rendition is the most taboo of all to mention. A rough approximation to it can be found in what remains in many ways the best account of the relationship between the two, Robert Kagan’s Paradise and Power, the benevolent contempt of whose imagery of Mars and Venus – the Old World, relieved of military duties by the New, cultivating the arts and pleasures of a borrowed peace – predictably riled Europeans.11 But even Kagan grants them too much, as if they really lived according to the precepts of Kant, while Americans were obliged to act on the truths of Hobbes. If a philosophical reference were wanted, more appropriate would have been La Boétie, whose Discours de la servitude volontaire could furnish a motto for the Union. But these are arcana. The one contemporary text to have captured the full flavour of the transatlantic relationship is, perhaps inevitably, a satire, Régis Debray’s plea for a United States of the West that would absorb Europe completely into the American imperium.12

Did it have to come to this? The paradox is that when Europe was less united, it was in many ways more independent. The leaders who ruled in the early stages of integration had all been formed in a world before the global hegemony of the United States, when the major European states were themselves imperial powers, whose foreign policies were self-determined. These were people who had lived through the disasters of the Second World War, but were not crushed by them. This was true not just of a figure like De Gaulle, but of Adenauer and Mollet, of Eden and Heath, all of whom were quite prepared to ignore or defy America if their ambitions demanded it. Monnet, who did not accept their national assumptions, and never clashed with the US, still shared their sense of a future in which Europeans could settle their own affairs, in another fashion. Down into the 1970s, something of this spirit lived on even in Giscard and Schmidt, as Carter discovered. But with the neo-liberal turn of the 1980s, and the arrival in power in the 1990s of a postwar generation, it faded. The new economic doctrines cast doubt on the state as a political agent, and the new leaders had never known anything except the Pax Americana. The traditional springs of autonomy were gone.

By this time, on the other hand, the Community had doubled in size, acquired an international currency, and boasted a GDP exceeding that of the United States itself. Statistically, the conditions for an independent Europe existed as never before. But politically, they had been reversed. With the decay of federalism and the deflation of inter-governmentalism, the Union had weakened national, without creating a supranational, sovereignty, leaving rulers adrift in an ill-defined limbo between the two. With the eclipse of significant distinctions between left and right, other motives of an earlier independence have also waned. In the syrup of la pensée unique, little separates the market-friendly wisdom of one side of the Atlantic from the other, though as befits the derivative, the recipe is still blander in Europe than America, where political differences are less extinct. In such conditions, an enthusiast can find no higher praise for the Union than to compare it to ‘one of the most successful companies in global history’. Which firm confers this honour on Brussels? Why, the one in your wallet. The EU ‘is already closer to Visa than it is to a state’, declares New Labour’s Mark Leonard, exalting Europe to the rank of a credit card.

Transcendence of the nation-state, Marx believed, would be a task not for capital but for labour. A century later, as the Cold War set in, Kojève held that whichever camp achieved it would emerge the victor from the conflict. The foundation of the European Community settled the issue for him. The West would win, and its triumph would bring history, understood categorically – not chronologically – as the realisation of human freedom, to an end. Kojève’s prediction was accurate. His extrapolation, and its irony, remain in the balance. They have certainly not been disproved: he would have smiled at the image of a chit of plastic. The emergence of the Union may be regarded as the last great world-historical achievement of the bourgeoisie, proof that its creative powers were not exhausted by the fratricide of two world wars, and what has happened to it as a strange declension from what was hoped from it. Yet the long-run outcome of integration remains unforeseeable to all parties. Even without shocks, many a zigzag has marked its path. With them, who knows what further mutations might occur.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.