Sir Roger Tichborne is my name,

I’m seeking now for wealth and fame,

They say that I was lost at sea,

But I tell them ‘Oh dear, no, not me.’

This ballad, sung in procession when the Tichborne Claimant appeared at the Grand Amalgamated Demonstration of Foresters at Loughborough in August 1872, neatly compresses the story of the most celebrated of all late Victorian causes. In the spring of 1854, Roger Tichborne, a roving, hard-drinking ex-dragoon, took ship on the Bella bound for Kingston, Jamaica, out of Rio, the only passenger alongside a cargo of coffee. Neither Roger nor the ship was ever seen again. His mother, Henriette, refused to believe that he was dead. An old sailor turned up at Tichborne House begging for cash and, when asked whether he had ever heard of the Bella, said he had heard that the crew ended up in Australia. A few years later, Henriette placed advertisements in newspapers all over the world. In due course, a bankrupt butcher in Wagga Wagga, originally called Arthur Orton though at the time going by the name of Tomas Castro, slyly admitted that he was indeed Roger Tichborne, who would by now have been a baronet and the owner of the large Tichborne estate in Hampshire. And on Christmas Day 1866 he arrived in London to claim his inheritance.

It is hard to think of any respect in which the Claimant resembled Roger. He was already 13 and a half stone, in contrast to the wraithlike Roger, and was to reach massive proportions, 28 stone 4 lbs, by 1871. Though Roger was half-French and had grown up in France, the Claimant couldn’t speak a word of the language. Roger later attended Stonyhurst College; the Claimant was barely literate. The best that could be said for him was that he waggled his eyebrows in a way that reminded his supporters of Roger. Nor was his original identity much obscured: when he recklessly visited Wapping on arriving in London, he was immediately identified as the long-lost Arthur Orton.

Yet in no time he became a national hero. When his waxwork went on view at Madame Tussauds, the queues had stretched out into the street. A demonstration in his support in the London docklands drew a bigger crowd than the one that welcomed Garibaldi. On his West Country tour, up to four thousand people crowded into Bristol Temple Meads station to catch a glimpse of him. The funambulist Blondin offered to carry him across Niagara Falls, though the Claimant declined, protesting in his characteristic deadpan style: ‘I think I am a little bit too heavy.’ His cause was coupled with that of Magna Carta and fair play for every Englishman. Between 1874 and 1886 no fewer than 251 Tichborne and Magna Carta organisations came into being, not to mention dozens of newspapers devoted to his cause, such as the Tichborne and People’s Ventilator.

Other causes became attached to Tichbornism: among them, the campaigns against compulsory vaccination and wrongful imprisonment in lunatic asylums. He attracted supporters from every age and class, particularly those who felt that life had given them a raw deal. He was the toast of the racecourse and the music halls. The diminutive Harry Relph began his career in blackface, as ‘Young Tichborne, the Claimant’s Bootlace’, soon to be abbreviated and immortalised as Little Tich, whence ‘tich’ and ‘tichy’ – a delicious way to remember the gargantuan Claimant. Those who took a class-based view of things were bewildered and infuriated by the whole business. Shaw, in the preface to Androcles and the Lion, mocked the contradiction involved in the case of ‘the Tichborne Claimant, whose attempt to pass himself off as a baronet was supported by an association of labourers on the ground that the Tichborne family, in resisting it, were trying to do a labourer out of his rights’. Ruskin deplored ‘the flood of human idiotism’ and ‘the loathsome thoughts and vulgar inquisitiveness’ provoked by the case.

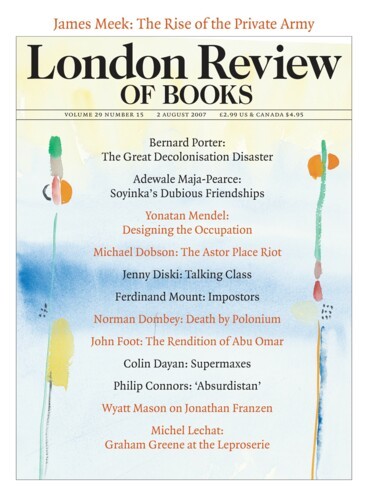

In this new study, Rohan McWilliam argues that ‘the Tichborne cause reveals a mosaic of mentalities and attitudes that we still do not fully understand.’ He tells the story with a lucid command of narrative and an understated wit, but here and there we catch a whiff of the PhD out of which the book arose. McWilliam devotes much of the second half of the book not so much to the case itself as to the proposition that ‘the Claimant forces us to view the development of modern mass politics and the movement towards democracy in new ways.’ I’m not sure that he works this line out to his own satisfaction. Yes, the Tichborne agitations did coincide and overlap with progressive organisations and causes, such as votes for women, but he also notes that Tichbornism had in it a strong element of popular Toryism and nostalgia for the days before the Norman Yoke. Rather despairingly, McWilliam concludes that ‘the best way to think of it is as a form of pastiche.’ Pastiche of what exactly, and who is doing the pastiching?

McWilliam repeatedly tries to anchor the affair to a unique set of historical circumstances and to integrate it with emerging political processes. We are told, for example, that ‘Tichbornism was undoubtedly part of a new world of mass communications characterised by the culture of sensation,’ for ‘Victorians were in thrall to sensation of all kinds.’ They were especially interested in doubles, because ‘the Victorians lived double lives, divided between public and private.’ But you can substitute for ‘Victorians’ in these assertions (and there are quite a few more of them) almost any epoch-dwellers you fancy – Edwardians, Georgians, Tudors – and sound no more and no less plausible. McWilliam himself is reminded of the popular enthusiasm for Queen Caroline after the Prince Regent had been so horrible to her. We are more likely to think of Princess Diana, who, allowing for weight and age, triggers many of the same responses. Reading about the huge crowds that sang the Claimant to Newgate and greeted him on his release and crowded into Paddington Cemetery for his pauper’s funeral, one cannot help thinking of that eerie wail that ran along the waiting crowds as Diana’s funeral cortège set off from Kensington Palace.

Here and there McWilliam does catch a glimpse of the Claimant as a more timeless figure: a modern lord of misrule, the ultimate inappropriate person. His childlike greed, his knee-jerk lusts, his refusal to be cast down, make him irresistible in a ghastly sort of way, and it is hard not to sympathise with him through all the ordeals he brought on himself. The two trials he went through, one civil and the other criminal, were two of the longest in British legal history until the McLibel trial. The presiding judge at the criminal trial, Lord Chief Justice Cockburn, said, in sentencing the Claimant to 14 years in jail for perjury (because of the lies he had told in the civil suit to gain possession of the Tichborne estate): ‘Never was there a trial in England, I believe, since that memorable trial of Charles I, which has excited more the attention of Englishmen and the world than this.’

It is as though the establishment of someone’s identity was the most difficult and most crucial task that a court could undertake. McWilliam has fun with the overblown oratory and melodramatic courtroom tactics of the barristers in the Tichborne case, but what strikes one more is the painstaking gathering of evidence from all over the world, investigators being despatched to Australia and South America and a flock of witnesses brought to London at huge expense. No one who had had the slightest acquaintance with Arthur Orton or Roger Tichborne was overlooked.

Similarly, Anna Anderson’s equally unsuccessful battle to be recognised as the Grand Duchess Anastasia was the longest-running 20th-century German court case. The trial brought on stage every surviving member of the Russian court who could be found, as well as all Anna Anderson’s childhood friends and relations. The whole affair further exemplifies the strange atmosphere that surrounds every impostor craze, the way in which identity becomes fluid, provisional, various. Even Gleb Botkin, the son of the last tsar’s doctor and the most loyal of the false Anastasia supporters, acknowledged that Siberia was swarming with Romanov impostors. By 1920, there were four purported Grand Duchess Tatianas. The lawyer hired by the opposition claimed to have interviewed 14 other Grand Duchess Anastasias. By the end of Anna Anderson’s life, no fewer than 30 women had come forward claiming to be the daughter she herself had given away for adoption.

The Claimant had at least two earlier aliases before he settled on ‘Roger Tichborne’, and Anna had several months as a putative Tatiana before she settled on Anastasia. Anna was originally a Polish peasant called Franziska Schanzkowska. She was hauled out of the Landwehr Canal in Berlin on 18 February 1920. The police found no identification on her and she refused to say a word. She was taken to the Dalldorf asylum and registered as Fräulein Unbekannt. It was here that a fellow inmate, Clara Peuthert, said to her: ‘Your face is familiar to me, you do not come from ordinary circles.’ Anna refused to answer. Later, a copy of the Berliner Illustrierte Zeitung was brought into the asylum with an article about the tsar’s murder captioned ‘Is one of the daughters alive?’, and Clara said to Miss Unknown: ‘I know who you are. You are Grand Duchess Tatiana.’ Again Anna refused to speak, then went along with the identification, then changed her mind after a former lady-in-waiting to the tsarina visited the asylum and said that Anna was too short to be Tatiana. But her supporters refused to give up on the idea of her being one of the grand duchesses. Because she wouldn’t speak, they gave her a list of the girls’ names, asking her to cross out the ones that were not hers. She crossed out all except Anastasia.

Anna Anderson was five years older than the real Anastasia and, like the Claimant, bore little physical resemblance to the person she was impersonating, being square-jawed and hawk-nosed, where Anastasia had a longer, softer face. Nor could Anna speak Russian or French, as any Russian princess would have been able to. Like the Claimant, she was taciturn and brusque in manner, usually refusing to offer details of her past life, having had several bosh shots to start with. She had claimed that on the night of the shootings the tsarina had been ‘half-fainting with fear and … almost unconscious – she perhaps took in least of the appalling things that were happening to us all.’ Unluckily for Anna, members of the execution squad who saw the imperial family passing by on their way to the cellar recalled them looking remarkably relaxed and cheerful – and why not, as they thought they were merely being taken down to be photographed? Safer, therefore, to say instead, as Anna did later: ‘I remember nothing of these things.’

The impostor’s hidden weapon is the belief of conventional society that to keep up a false personality must be impossibly difficult. Dr Hans Willige, in declaring Anna sane, asserted that ‘to be able to impersonate another would require a surpassing intelligence, an extraordinary degree of self-control and an ever-alert discipline – all qualities Frau Tschaikovsky in no way possesses.’ (Frau Tschaikovsky was Anna’s official name at the time.) But in reality no such qualities are required, only a mulish determination to keep it up and a certain opacity and bad temper to keep doubters at bay. The willing suspension of disbelief by others does the rest. Frances Welch takes as the epigraph to her entrancing account of Anna’s story the maxim from Ship of Fools: ‘The World wants to be deceived.’ Welch has no thesis to grind out beyond the demonstration of this truth, which emerges all the more clearly as a result.

An impostor’s howlers will be put down to the trauma he or she has suffered, and the slightest evidence of similarity will be seized on with relief, such as the news that when the Claimant took up country pursuits he chose the same fishing flies that Roger had favoured. Science of a sort was wheeled on in support of one thesis or another. An anthropologist told the court in Hamburg that the resemblance between Anna and Anastasia was so close that they must be either the same person or identical twins. Another expert detected 17 points of identity between their right ears. A graphologist found 137 identical characteristics in their handwriting. By contrast, the graphologist in the Tichborne trial said that the Claimant’s handwriting matched Orton’s and was nothing like Roger Tichborne’s. On the other hand, Guildford Onslow MP, the Claimant’s most dogged supporter among the upper classes, issued a pamphlet listing 200 facts proving the Claimant to be Roger.

Serious science finally made its debut in 1994, when the DNA from a piece of Anna’s intestine was compared with samples taken from Prince Philip and the Romanovs on the one hand, and with a blood sample from a relative of Franziska Schanzkowska on the other. The test proved emphatically that Anna was related to the Schanzkowskis and not to the Romanovs. This of course did not prevent her supporters claiming that there had been a mix-up or tampering of some kind. Even the most principled rationalists are reluctant to abandon a crusade in which they have invested so much. After a lifetime’s campaigning to prove James Hanratty’s innocence, the incorruptible Paul Foot refused to accept the DNA evidence that after all Hanratty had raped Valerie Storie and therefore must have been guilty of the A6 murder.

Ultimately, we are not dealing with rival scientific theories. We are dealing with acts of faith. It is no coincidence that the most passionate supporters of the Claimant and Anna Anderson went on to found religious sects of their own. E.V. Kenealy, a QC and briefly MP for Stoke, defended the Claimant with bravura at the criminal trial. A lapsed Catholic, he saw himself in a line of messianic teachers, stretching from Adam and Jesus by way of Muhammad and Genghis Khan. He claimed to be the Twelfth Messenger to whom the truth about the Apocalypse had been revealed. Gleb Botkin also took the leading part in the church he founded, the Church of Aphrodite, a fun-loving religion which had a concept of heaven but no hell and no negative commandments. On his altar, Botkin had a five-foot plaster copy of the Venus de Medici. His makeshift chapel seated only ten, so, as Frances Welch points out, it was just as well that the congregation ranged from three to seven.

Of course some supporters (and opponents) of any imposture will have material and mercenary motives. The motley band of German princelings and American millionairesses who backed Anna dreamed of replacing the Bolsheviks. Both Anna and the Romanovs who ganged up against her had their eye on the tsarist millions supposedly lying dormant in foreign bank accounts. But they were piggy-backing on the genuine faith of masses of people who believed they had undergone a recognition experience.

Most fascinating of all, I think, is the way in which claimants themselves understand that they cannot bluntly assert their identity. They must be recognised. There must first be a process of suggestion and search undertaken by others: Henriette’s advertising campaign; the article raising the possibility of survivors from the tsar’s murder. Then the impostor must lead on the potential recogniser. It was Clara Peuthert who first said that Anna was someone extraordinary. Anna herself said nothing but raised her finger theatrically to her lips, allowing Clara to come in her own time to the conclusion that she was one of the grand duchesses. Arthur Orton/Tomas Castro casually mentioned to the lawyer in Wagga Wagga that he had been involved in a shipwreck and was entitled to some property in England. But it was the lawyer who came up to him and said: ‘I know your real name.’ Even then Castro acted coy, although he let the lawyer see that his pipe had the initials R.C.T. scratched on it. The pigeon was soon fluttering in the trap.

The successful impostor seems to possess an instinctive understanding of the rules of anagnorisis, which thinkers since Aristotle have made such a fuss about. The audience must be allowed their moment of truth in which their eyes are at last opened. The whole process exposes how precious and fragile is our command of identity, and how rough and physical are our methods of establishing it. The word identity derives from idem, ‘the same’, by way of identidem, meaning ‘repeatedly’. To identify, literally and originally ‘to make the same as’, involves a repeated pointing at a thing or person to confirm that it remains the same through space and time. That is how we assure ourselves of the reality of everything, including ourselves. It is a reassurance, but also a constraint. There is a dizzy delight to be had from breaking free and declaring that we can be whoever we want to be. A bankrupt butcher can be a baronet; a no-hoper fished out of a canal can be a grand duchess. The greater the improbability, the more marvellous the translation – as Borges reminds us in ‘The Improbable Impostor Tom Castro’. Borges is only one of the many writers who were drawn to use the story in one way or another, among them Trollope, Patrick White, Robin Maugham and Julian Symons, just as Dumas, and Boublil and Schönberg, have pounced on the story of Martin Guerre, and Verlaine, Georg Trakl and Peter Handke, not to mention a dozen playwrights and film-makers, have taken up the tale of Kaspar Hauser.

These days the celebrity machine has taken over the translation business: Bottom’s dream is acted out on Big Brother. But the allure of the old style lingers on. As I was beginning this review, I saw a story on the front page of the Daily Telegraph (25 May) headlined ‘Prince in the Tower “died a bricklayer”.’ The report, later taken up by other papers, was based on a book by David Baldwin, who asserts that the elder prince, the deposed Edward V, died of natural causes and that, after Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth, the younger, Richard of York, was taken to St John’s Abbey in Colchester, where he worked as a bricklayer. The book is almost as extraordinary a production as the story it tells. It is garnished with the usual scholarly apparatus of notes and bibliography, and much of the time pursues apparently rational sequences of argument. Baldwin even makes amiable concessions to the sceptics before shooting off again into the wildest flights of fancy. ‘The potential stumbling block,’ he tells us with apparent humility, ‘is the absence of anything that a modern court of law would accept as proof.’ No, it isn’t. The very real stumbling block is the absence of any evidence at all, either that Richard survived, or that he ever went near Colchester. Why bricklaying anyway? Well, Baldwin tells us, bricklaying was a growth industry in late 15th-century Essex. So what? If Richard was alive, he might just as well have been a rope-maker in Bridport or a cobbler in Northampton.

Baldwin also lets us know about ‘another, more controversial, source that must be included in any impartial survey of the problem’. This is a book published in 1996 by a retired Anglican priest, the Rev. John Dening, who describes a number of contacts he had with Richard III and also Edward IV, effected through a spiritualist medium called Bryan Gibson. During these long-range interviews, Richard apparently told Dening via Gibson that the princes had indeed been smothered in the Tower, though this had not been his intention. Although this news from the Other Side would seem to explode Baldwin’s own theory, he is inclined to give it house-room because, like a good Ricardian, he seizes on anything showing no-longer-Crookback Dick in a faintly positive light. There is, we are told, no evidence that Richard meant the princes any harm: he was under terrible pressure from the forces supporting Edward IV’s widow and really the only solution for the poor stressed-out fellow was to become king himself.

By now one’s head is reeling. But there is a further twist. When the monasteries are dissolved, the bricklayer-prince wanders the Home Counties and fetches up in Eastwell, in Kent, where he attracts attention because he can speak Latin and, when pressed, reveals that he is, no, not Richard of York but an illegitimate son of Richard III, also called Richard, who was taken to see his father on the eve of Bosworth. Quite why he would spin this story at a time under the early Tudors when Richard III was hardly a popular figure seems bizarre. Nor is there the slightest scintilla of evidence to link this Richard of Eastwell (if he ever existed – the first mention of the story is in an 18th-century anecdote) with Richard of York. The book concludes with a photograph of the Richard III Society paying a visit to the supposed grave of Richard Plantagenet at Eastwell in 1964. They are a very respectable bunch, the gentlemen in suits, ties and raincoats, the ladies with hats and handbags. One stumbles out of the pages of The Lost Prince marvelling at the infinite playfulness of the human mind.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.