Better to wonder if ten thousand angels

Could waltz on the head of a pin

And not feel crowded than to wonder if now’s the time

for the armies of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

To teach the Serbs a lesson they’ll never forget

For shooting Archduke Franz Ferdinand in SarajevoCarl Dennis, ‘World History’1

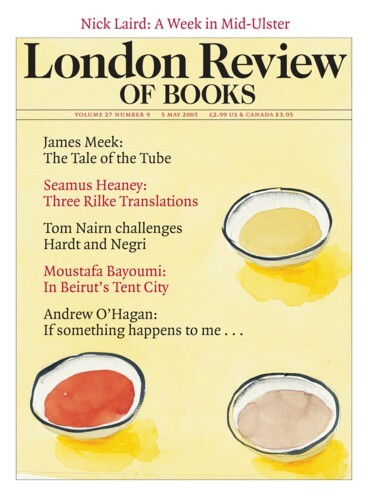

The cover of Multitude invites bookshop browsers not just to read it, but to ‘Join the many. Join the Empowered.’ The missionary tone is underlined by Naomi Klein’s blurb – ‘inspiring’ – and a frisson added by the book’s appearance: a brown paper wrapping like those used to discourage porn thieves and customs inspectors. Trembling fingers that go further are reminded that this book succeeds Empire (2000), by the same authors, which provided a picture of the global imperium supposed to have followed the Cold War – not the American Empire, but a wider settlement of which US supremacy was just one part. This imperium has generated global resistance, which all purchasers are now invited to approve, in the name of democracy.

Hardt and Negri’s multitude should not be confused with the working class, or any ethnic and national group. It seems to mean humanity in general – ‘The multitude is many-coloured, like Joseph’s magical coat,’ but the coat hides an increasingly common will, summed up by the authors as ‘democracy’. Readers are warned that the book’s argument may not be ‘immediately clear’ and are exhorted to be patient, for Multitude is ‘a mosaic from which the general design gradually emerges’. Before turning to that design, it’s important to stress how welcome this expansiveness is. In a venture like this, social anthropology and philosophy are as important as economics or conventional international relations. As Gopal Balakrishnan wrote in his review of Empire in New Left Review, it seems apposite to cite Virgil: ‘The final age that the oracle foretold has arrived; the great order of the centuries is born again.’

And yet, as in the previous book, this oracular tone is puzzling. If the outlook for global democratisation were as good as these prophets maintain, then surely a more empirical, matter-of-fact tone would suffice? Instead, an exalted and visionary tone prevails, right up to the high note of rapture on which they end: ‘Today time is split between a present that is already dead and a future that is already living … In time, an event will thrust us like an arrow into that living future. This will be the real political act of love.’ Hardt and Negri’s project is constantly undermined by an inebriate tendency towards the absolute. It is as if the authors find themselves transported by a philosophical elixir of oneness which, though invariably justified as ‘radicalism’, may in fact carry the reader towards an odd style of religiosity. Nor is this just a side effect: it is this that we are really being invited to ‘join’ – empowerment through faith, via spiritual transport.

You’ll have to tell them frankly you can’t explain

Why Nineveh is still standing though you hope to learn

At the feet of a prophet who for all you know

May be turning his donkey toward Nineveh even now.Carl Dennis, ‘Prophet’

While Empire made some readers think of Virgil and Rome, in Multitude the defining shift is more restricted: the postmodern has become the premodern. The philosophy of Spinoza has replaced both Marxism and capitalist neo-liberalism. While affected timelessness is inherent in the Hardt-Negri rhetoric – hence their over-easy references to antiquity or the Middle Ages – the centre of gravity in this book is firmly in the later 17th century. Once regarded as an important precursor of the Enlightenment and of Marxist materialism, the thought of Spinoza (1632-77) is redeemed in these pages, as a wisdom awaiting its vindication in a globalised epoch yet to come. In vital ways, Spinoza told the whole story: his apparently abstract pantheistic philosophy explained history itself, future as well as past, and the globalisation process simply favours a return to such understanding, after the mounting sorrows and delusions of modernity.

Spinoza was an asylum seeker fortunate to find refuge in the Netherlands. Under the more stable conditions following the Thirty Years War and the Treaties of Westphalia, his family settled in one of Europe’s most open and prosperous societies. This fascinating world has been brought to life by Jonathan Israel’s great study, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity (2001). But Israel isn’t mentioned in Multitude’s extensive notes. Hardt and Negri’s concern is with rebirth, not historiography. It is the great seer who appeals to them: ‘the spiritual saboteur, a subverter of things lawfully established, and an apologist for the Devil’, as Roger Scruton has put it, who ‘after his death was regarded as the greatest heretic of the 17th century’.

Reviled both by orthodox Hebraism and many Netherlands Calvinists, Spinoza insisted that intuitive prophecy was the basis of true faith, and that ‘the prophet creates his own people.’ In Radical Enlightenment Israel claims that Spinoza’s system ‘imparted shape, order and unity to the entire tradition of radical thought, both retrospectively and in its subsequent development’, and Spinoza’s Ethics concluded in terms significantly like those of Multitude: ‘The intellectual love of God … is eternal,’ and ‘there is nothing in nature which is contrary to this intellectual love, or which can take it away.’ It has taken a while for ‘the people’ to show up as global everybody or multitude; but this is good luck for our authors, as they do not hesitate to remind readers. Thanks to the Western victory in the Cold War and to information technology, can it be that globalisation is putting the whole world into the hands of today’s radical heretics?

Spinoza was a republican democrat and a supporter of the politician Johan De Witt (1625-72), an opponent of the House of Orange. After De Witt’s death, the aristocratic Orange faction took power and restored a more conventional social order (which was subsequently imposed on Britain when one of them acquired the English throne in 1689). By that time ‘Spinozism’ was already a thriving underground cult with ardent supporters in many countries: ‘The battle was on to fix the image of the dying Spinoza in the perceptions and imagination of posterity,’ Israel writes, since ‘the final hours of a thinker who seeks to transform the spiritual foundations of the society around him become heavily charged with symbolic significance in the eyes of both disciples and adversaries.’ Plainly, this battle still continues. It is not to disregard or minimise such a striking lineage to observe that Spinozism had limitations associated with the society it came from, in which countries were struggling to emerge from absolutism and theocratic tyranny. Today, Spinoza’s greatness has to be defended against the delusions of a belated progeny, rather as Marx had to be in the later 19th and 20th centuries.

Among this progeny, as in the 17th century, heresy underwrites faith. Disowning an orthodoxy makes for a purer belief, rather than its demolition. The heretic normally believes self-consciously that he has some new access to the secrets of the universal essence – as revealed in a Da Vinci code, for example, or in significant recent happenings, or both. In this case, the people being fostered by prophecy are a ‘network’, contemporary academese for those ‘born again’: souls meshed together not just by experience but by a cultural sensibility which is by definition universal (or cosmopolitan) in its direction and meaning. It would be old hat to speak of ‘spirit’; but Spinoza’s system proves useful at this point. His pantheism identified matter and mind, and the Deity, with the Universe itself; and, in similar vein, secularism can now be merged with spiritualism. Dreary old historical materialism can thus be retrieved and re-wardrobed as an idealised globalisation, an object of belief requiring no denominations, sects, rituals or oaths (only £20 over the bookshop counter).

Readers of Empire were puzzled about just whose empire was at stake. The dawning Oneness was emphatically dissociated from the most obvious candidate, victorious American imperialism. Indeed, as Balakrishnan observed in his review, the authors repeatedly cited American revolutionary and constitutional precedents for the style of global liberation they were preaching. This pattern is continued in Multitude. But while in 2000 the notion of the multinational US as flawed staging-post towards the Absolute remained merely difficult, in 2005 it has become absurd. Between book launches, a war launched by super-heated American nationalism has lurched onto the scene with a distinct message of its own.

In the pages of Multitude, however, all this is curiously sidelined. As some suspected from the start, the empire turns out to be God’s own: a permanent if ethereal ascription, not threatened but rendered more evident by the valley of shadows we have been dragged through since 2003. All conflicts are now redefined as ‘civil wars’ within this overmastering Totality, an end-time so final that all detours appear futile. President Bush’s descent on Iraq is just one of these: not an aberration or a relapse into old-fashioned imperialism, but characteristic of the new age. That is, of a globe that has become truly One, though still awaiting the signal-flares of true redemption.

And in this dark meantime, Satan has taken over.

You try to imagine highways to all men

But your heart has always loved boundaries,

The heavy fields in back of your house, the visible streets of America.Carl Dennis, ‘Native Son’

Hence the vale of sorrows recounted by ‘Simplicissimus’ in the first section of the book. In the absence of love, war has overwhelmed creation. Globalisation’s first step has been a Fall, a descent into an abyss: ‘War is becoming a general phenomenon, global and interminable.’ Postmodernity so far is doom; golems have taken over the globe and bathed their enemies in blood, while clerics and footling liberals either egg them on or mutter futilely about peace. The golem-world is not a passing phase but a ‘new ontology’, demanding some equivalently total, all-encompassing answer. Le Monde diplomatique’s current atlas of conflicts lists about 65 wars or agitations; but Hardt and Negri discern ‘almost two thousand sustained armed conflicts on the face of the earth at the beginning of the new millennium, and the number is growing’. No list is attempted, and the three examples cited are Rwanda, the Croat-Serb wars and ‘Hindu and Muslim violence in South Asia’ (presumably in Kashmir). Anyone can add significantly to this list – Aceh, East Timor, Eritrea, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Tibet, Darfur, Chechnya, Kurdistan etc – but it is difficult to approach anything like the apocalyptic vision unveiled for readers of Multitude.

We are being told of an endless 9/11, a climacteric of world history, but there is little doubt that warfare is now less of a universal threat than it was between the 1950s and the 1980s. Some years back Donald MacKenzie argued in the LRB that – contrary to so many earlier previsions – nuclear weapons had been in effect ‘disinvented’ by the closure of the Cold War, and the colossal, escalating investment in both material and human resources needed to make them work was bound to diminish.2 Now, in spite of 9/11, Iraq and the proposed US Defense Shield, Armageddon has retreated further. In The Globalisation of World Politics (2001) Michael Cox pointed out that today ‘nuclear war is far less likely to happen,’ even though there has been an increase in the number of wars. Later in the same volume Andrew Linklater maintained that ‘there is no doubt that globalisation and fragmentation have reduced the modern state’s willingness and capacity to wage the kinds of war which typified the last century.’ America, Britain and some cronies may have lapsed into this sort of war in 2003: but that’s what it was – a throwback, not some new ontology.

The point is not just that Multitude uncannily echoes the feigned panic of Washington anti-terrorists. This is a philosophical argument that ordains extremes. An unremitting Vale of Despond is required, because the coming vision of transfiguration must be equivalently comprehensive – a view expounded in Negri’s Subversive Spinoza: (Un)contemporary Variations.3 Hardt and Negri are in the Redemption business, door-steppers rather than private eyes. Nor should it be thought such metaphysical transports are confined to their two books, or to small coteries of addicts. Plenty of others were on the trail in the 1980s and 1990s, especially in France. They included Jacques Lacan, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, as well as a Duke University elite in the US. In a survey of the trend in the journal Anthropoetics in 1997, Douglas Collins wrote that back in 1984 Julia Kristeva had noted that ‘we’re in the middle of a regression which is present in the form of a return to the religious … a rehabilitation of spiritualism.’ Spinozism was part of this: ‘the latest example of French totalism, a product of the nostalgia for the universalising vocation of the French intelligentsia, seeking new grounds to assert the prerogatives of its historical role, refusing to allow itself to be consigned to Pareto’s “graveyard of aristocracies”’.

Many readers will sense something odd about such reliance on a vision predating not only David Hume and Adam Smith, but Darwin, Freud, Marx and Durkheim, from an age when genes and the structure of human DNA were undreamt of. Can philosophy really be so timeless? The answer is plainly yes, provided a sufficiently passionate sermon can be extracted out of it, for delivery to a sufficiently huge and eager congregation of the disoriented, looking for omens of a new century. Naturally, those disenchanted with neo-liberal progress are thirsty for portents of a fairer dawn. And some will prefer it in secular rather than theological garb, however surprising or unfamiliar the source.

Another striking expression of this trend is Etienne Balibar’s Spinoza and Politics (1998), the preface of which stresses its connections with Negri’s work in the 1970s. Balibar, too, ends with pages of rapturous merging, showing how the Spinozan framework identifies everything with everything else, including politics, and thus restores a universalist vocation to the intelligentsia: ‘Politics is the touchstone of historical knowledge. So if we know politics rationally – as rationally as we know mathematics – then we know God, for God conceived adequately is identical with the multiplicity of natural powers.’

So how come He/They wrecked things with George W. Bush? Why did the highways to all men give way to those heavy fields in back of home? Christian Pentecostalists and Wahhabite Muslims alike think they know God, and that their particular boundaries are imbued with universal spirit and meaning. These boundaries must be fought for, plainly, rather than relying on mathematical reason for an answer. And such combat continues to demand mobilisation of the inhabitants of the nations within these boundaries. Only as a staging-post towards the conversion of everybody, everywhere, of course. But this is notoriously clearer to missionaries than to the denizens of know-nothing darkness. Thus the touchstone of actual political history would appear still to be somewhere specific – this or that goddam backyard or visible street – rather than up in the ether of universal being and implication. And somewhere always implies somewhere else: recalcitrant, differing elsewheres, beyond this or that boundary – or possibly (one suspects) beyond every one of the frontiers and diverse identities that have, so far, structured a necessarily disruptive and nomadic species. Undismayed by the post-2001 setback, Hardt and Negri turn nonetheless to look for signs of coming redemption through the smog of their fallen world.

Be like those angels said to enjoy the earth

As a summer retreat before man entered the picture,

Staggering under his sack of boundary stones.

They didn’t mutter curses as they fastened their wings

And rose in widening farewell circles.

They grieved for the garden growing smaller below them,

Soon to exist only as a story

That every day grows harder to believe.Carl Dennis, ‘Loss’

‘Multitude’ is defined in Webster’s as ‘the state of being many’, with an implication of formlessness or indeterminacy: ‘a multitude of sins’ is probably its most common use. The same dictionary goes to Claud Cockburn for its adjectival example: ‘The mosquitoes were multitudinous and fierce.’ Hardt and Negri attempt a more positive definition, laying emphasis on signs of grace, and attendant democratic virtues. But this turns out to be curiously like the bus tours found in all big cities. Sightseers impatient for the general design get whisked at speed past famous landmarks, as the guide intones a suitable (often rather similar) judgment on each one, with too few dodgy jokes. The guides in this case are invariably erudite: their references take up 45 pages, and great efforts are made with innovative concepts such as network struggles, ‘swarm intelligence’, ‘biopower’ (‘engaging social life in its entirety’), immaterial labour, and the multitudinous spirit as carnival (‘a theory of organisation based on the freedom of singularities that converge in the production of the common: Long live movement! Long live carnival! Long live the common!’). The ‘monstrosity of the flesh’ gets a look-in as well, though rendered decent as Man, ‘the animal … that is changing its own species’.

Yet this erudite tour leads only to an inconclusive emptiness, where the signs portend some somersault to come, via an unprecedented agency that may be everywhere, and potentially omnipotent, yet remains without a local habitation and a name. In Chapter 2, religions, nations, classes and existing transnational bodies are indeed acknowledged as contributing to the moment of advent – that is, to a process of ‘making common’ whose pattern will be quite different from anything previously experienced. All sorts of omens are read as indicating the way forward out of modernity’s blood-drenched darkness. But how?

Take the case of anthropology. The great lurch forward into market-driven unification – suggesting a world in some ways akin to one nation and state – was bound to reawaken concern about human nature, the grander parameters of the species now so brusquely confined to ‘one boat’. And indeed it is noted that anthropologists are moving towards a new paradigm by ‘developing a new conception of difference, which we will return to later’. Yet when this conception subsequently materialises, it is as follows: ‘We are a multiplicity of singular forms of life and at the same time share a common global existence. The anthropology of the multitude is an anthropology of singularity and commonality.’ This disappointingly bland aperçu is supported by a footnote referring readers not to Barth, Gellner or Geertz, and certainly not to such historical revisions as Hugh Brody’s The Other Side of Eden (2001), or Stephen Oppenheimer’s Out of Eden (2003), let alone to such disturbing stuff as Chris Knight’s Blood Relations (1995), or remarkable surveys like Jonathan Xavier Inda and Renato Rosaldo’s The Anthropology of Globalisation (2001). No, on this crucial aspect of prehistory, the reader is referred instead to Deleuze’s Expressionism in Philosophy: Spinoza (1990).

Thus (again) speaks Spinoza, sufficient for the multitude. His ism can still embrace everything, including things and ideas born long after him (and which could not have existed in the later 17th century). In fact, the authenticity of the multitude represents an apotheosis of the ism: that is, of a specific way of processing ideas that emerged in the mid-19th century, and has remained a distinctive feature of modernity. An ism ceased to denote just a system of general ideas (like Platonism or Thomism), and evolved into a proclaimed cause or movement – no longer a mere school but a party or societal trend. Ideas acquired banner headlines and ‘stood for’ an aim or tendency, and eventually for a civilisational choice: individuals could in turn stand for this choice, and be ‘conscripted’ on one side or another. Social development linked to industrialisation, urbanisation and the formation of nations was bearing formerly voiceless masses into the political picture. These had to be formed into appropriate groups, whether Italians, Liberals, Conservatives, socialists (or whatever).

Identity in a more than bureaucratic sense had arrived. Its artificers were new too: the intellectuals. As Gramsci wrote in the Prison Notebooks, the function of modern intellectuals is inseparable from being torn between past and future. Their task is to reconcile the ‘tradition’ of established rulers with the inescapable appeal of the new, whether by compromise or through rejection. The formation and reformation of ‘philosophies’ now meant something dangerous, or reassuring, and that was their stock-in-trade.

Spinozism is a last-ditch salvationist movement, aimed at redeeming the status of isms. It stands for ‘ismhood’, a necessarily total secular faith fusing conceptual satisfaction and moral-political guidance. The aim is redemption, guaranteeing the future of the intelligentsia in this postmodern, and post-everything sense. Entrancing the globe by multitude-speak, the role of intellectuals is to fuse the coat of many colours into a consummate internationalism. And what can the warp and woof of this fabric be, but politically correct love?

And if it’s hard to believe that spirit

Is anything more than a word when defined

As something separate from what is mortal,

It’s easy to recognise the spirit of the recruit

Not convinced his honour has been offended

Who decides it’s time to step from the line

And catch a train back to his cottage, where his wife and daughter

Are waiting to serve him supper and hear the

news.Carl Dennis, ‘World History’

In the last third of the 19th century, one ism became far more successful than all its competitors: nationalism. Staggering with the sacks of precious boundary-stones, it was the peasants, the petty bourgeoisies and the emergent working classes who won the race. That was what drove the angels off. Because the first duty of essences (once established) is to be essential, it came to be believed this victory must have been foreordained, was irresistible and – if not eternal – then at least very long-range in its effects. ‘Realism’ dictated a dominance of the foreseeable by the ism that had shown it worked. So universality was postponed until this had worked itself out, either by means of warfare, monotheist religious conversion, or ultra-strenuous moral preaching and example.

This belief was natural, and occasionally heroic; it was also mistaken. ‘Internationalism’, in the old sense creakily replayed by Empire and Multitude, was a part of the 1870-1989 nationalist world, not an answer to it. Like New Imperialism and Social Darwinism, it was a response to the force of circumstances. The ism of nationality was not rooted in nations or societal diversity, but had been grafted onto them from the 1860s onwards, had led to two world wars, and was congealed in place for a further generation by the Cold War. What it really expressed was fratricidal great-nation hegemony and competition.

The term ‘nationalism’ did not appear in what everyone still views as the 19th century’s outstanding denunciation of politicised nationhood, Lord Acton’s On Nationality (1862). But it was in use by 1872, and by 1882 it had infiltrated every major language. Soon it would become the nature of a new century: as Ernest Gellner liked to put it, the ‘second nature’ of modernity itself. He meant that as long as the conditions of modernity endured, there would be no escaping from it. Even small and would-be countries – liberal, Mazzini-inspired, peace-inclined populations without imperial ambitions – had to tool up accordingly.

What began in 1989 was the real deconstruction of this phase. Both the wealth and the meaning of nations began to struggle out from the chrysalis of the ism. In The Globalisation of World Politics Fred Halliday points out that nationalism has been ‘promoted by processes of globalisation’, and its paradox is to ‘stress the distinct character of states and peoples’ while itself being manifestly a global phenomenon. The phenomenon originated mainly in the 18th century, but its aggressive or ‘closed’ definition appeared only spasmodically until the 1870s, when the social revolt of the communards had a critical impact on the national downfall of imperial France, forcing a more militant and rigid ideology into being. Napoleon III and Bismarck between them inflicted ‘nationalism’ on the globe (and it’s appropriate that the French and Germans should now be jointly undoing it, inside the new constitutional structures of the European Union). More surprisingly, Halliday argues that nationalism ‘was only fully recognised as relevant by International Relations in the past two decades’.

Hardt and Negri’s blueprint for democracy is revealed in the long final chapter of Multitude. Having regained the invigorating wholeness of Spinoza’s 17th century, we are poised to move on. What postmodernity must now do is to move on to the 18th century, the century of revolutions. But of course today’s replay will be quite different, since the multitude will be able to discard the failures that ensued last time: ‘Back then the concept of democracy was not corrupted as it is now.’ It had not yet been diluted or betrayed by representative or parliamentary nonsense, or by notions of ‘vanguard parties’. Unlike the liberal bourgeoisie and the proletariat, globalised network-humankind will be capable of authenticity. That is, of ‘a radical, absolute proposition that requires the rule of everyone by everyone’.

The revolutionaries of 1688, 1776 and 1789 went wrong in believing that the city-states of antiquity were a suitable model for modern nations. Today’s analogous error is to think that modern nation-states are relevant to democracy on a global scale, when ‘what is necessary is an audacious act of political imagination to break with the past, like the one accomplished in the 18th century,’ but avoiding its snares. All that counts now is ‘becoming common’, the formation of comparable lifestyles and ideas the world over. This is the ‘biopolitical’, the very gist of the postmodern – the species-speak that Foucault described as ‘genealogies’, or ‘more precisely anti-sciences’. Biopolitics has no particular role for nations. It is striking that the countries on Hardt and Negri’s list of trouble-spots are largely sites of national emancipation struggles – ‘old-fashioned’ wars of liberation for which there can no longer be any justification, at least according to such peremptory and ideological views of globalisation.

Is it not reasonable to think that such struggles may, after the disappearance of Cold War shackles, result in attempts at new kinds of democracy, better forms of representation, closer links between societies and states? And that the smaller scale of such resolutions may be more favourable to experiments than the mastodons of earlier times? Or that armour-plated nationalism might, in these circumstances, give way to a more sustainable, outward-looking version? The new ontology thinks not. It seeks ‘a democracy without qualifiers’, unconstrained by conservative ‘ifs or buts’. There’s no use looking at boring comparative stories like Arend Lijphart’s Patterns of Democracy (1999) for clues to a way ahead. The US is bad enough, the authors concede, and has recently made ‘a mockery of representation’, but ‘no other nations have electoral systems that are much more representative.’ This bewildering judgment is rubbed in when they turn to Europe, an area where a growing number of observers have recently been detecting shy symptoms of progress. Forget it: ‘The European constitutional model … does not really address the issue of representation,’ and may even be making things worse.

All that counts is the Spinoza-viable: democratic absolution investing ‘all of life, reason, the passions, and the very becoming divine of humanity’. Every other strategy is bound to appear conservative, ‘non-radical’, when set against such a spiritual assault course, prescribed for the networked multitude of humanity. The authors actually use the phrase ‘May the Force Be with You’ in a subheading, as a prelude to their closing exhortations on ‘the insistent mechanism of desire’, as displayed in the multitude’s readiness for the advent of rupture/rapture, or at any rate of some event manifesting the latent power of universal love.

In ‘World History’ Carl Dennis says that no silence can compare to that of ‘bristling nations standing toe to toe in a field … given the need of great nations to be ready for great encounters’. This is what prompts the recruit to step from the line, and make for the boondocks. I suspect that reading Multitude may affect many in the same way. It summons the great, multitudinous nation of mankind to join in an even greater encounter with the Absolute, a Last Day of loving Judgment where all will be redeemed. Globalisation is merely the wave bearing everyone towards this end. It’s the vindication of old mystical intuitions of oneness and reconciliation with heaven, brought to fruition unexpectedly by capitalism’s post-1989 world reach. There is no shame in feeling like the recruit at this point, or in suspecting that globalisation may have (or also have) opposite effects to those extolled here. May not the boondocks and those multitudinous elsewheres perceive it as an opportunity to be more themselves than previously – to build on so many painfully assembled boundary stones, rather than witnessing them swept away by storms of love, as once by storms of war?

But, however misguided it is, some may still feel Empire and Multitude to be on their side, allied to democracy and the left. Susan Sontag wrote that ‘an idea which is a distortion may have a greater intellectual thrust than the truth; it may serve the needs of the spirit.’ But unfortunately, spiritual needs are served here by adventures onto a terrain already occupied by fundamentalists of varying hues, all ready with their own formulae for rapture and ecstasy. Each one has its own multitudes of the faithful, armed and ready for great encounters still to come. Norman Cohn, the historian of millennial thought, traces the idea back to Zoroaster (Zarathustra), who added the idea of a happy ending to previous visions of disaster: ‘a glorious consummation of order over disorder, known as “the making wonderful”, in which “all things would be made perfect, once and for all”’. Later the notion was transmitted via Hebraism to Christianity. In When Time Shall Be No More (1992), Paul Boyer gave a graphic account of how strong this belief remains among born-again Americans, and more recently still Anatol Lieven has underlined the rapport between such apocalyptic convictions and US political identity in America Right or Wrong (2004). Unfortunately, being on our side has in this wider context the sense of carrying our side over to their terrain: we too have our apocalypse, better than the rest.

No we don’t. Globalisation must be about burying such delusions, not reviving them. It’s for the boondocks and the bearers of boundary stones, not for intellectuals avoiding the graveyard of their kind of aristocracy through a rehabilitation of spiritualism.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.