To the left of the entrance to The Spanish Civil War: Dreams + Nightmares (the exhibition runs until 28 April) is the Sargent Room. At the moment it contains three big World War One pictures: Sargent’s own Gassed, Stanley Spencer’s picture of wounded men on stretchers in Mesopotamia and Nevinson’s of troops crossing a desolate, shell-pocked battlefield. To the right of the entrance are galleries with pictures from World War Two: Eric Ravilious’s paintings of empty rooms in pale stippled watercolour, Laura Knight’s group of women setting up a barrage balloon, emphatically modest and determined to be unheroic. The emotional tone of British war art goes down many notches from the First War to the Second and its manner becomes almost prim in its discretion.

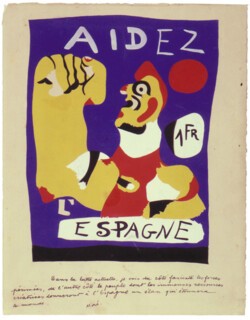

Between those wars a fair proportion of the forces of international Modernism attached themselves to the Republican cause. A little of what they produced is shown here, together with a fair sample of the material culture of the war: clumsy-looking weapons, tattered uniforms, books, posters, manuscripts, letters and film clips. This was the war of Picasso’s Guernica (there is a preparatory drawing); in Belgium the rumble of aerial warfare inspired Magritte’s picture of sinister flying machines against a night sky; in Britain poets tried for words adequate to its hopes and miseries – there are manuscripts of work by Auden, Spender and others. Modernism’s sympathies were egalitarian and with the Left, but in its demands and practices it was individualistic and elitist. The Republican defeat engendered a mood summed up in the accompanying booklet* by a quotation from Camus: ‘It was in Spain that men learned that one can be right and still be beaten, that force can vanquish spirit, that there are times when courage is not its own reward. It is this, without doubt, which explains why so many men throughout the world regard the Spanish drama as a personal tragedy.’

Modernism attached itself to the Left in part at least because words like ‘progressive’ seemed to point to a natural affinity. In Spain defeat came too soon for this to be tested, and Modernism never got a chance to show that it was essential to a general idea of progress – of things getting better.

But what would ‘getting better’ mean? It is from the letters that you get a rough idea of some of the hoped-for improvements which sent forty thousand or so foreign volunteers to fight in Spain. George Green, who went with his wife, wrote to his mother explaining why they were there just a few weeks before he was killed on the Ebro:

We came to war because we love peace and hate war . . . Fascism can be decisively beaten in Spain & if it is beaten in Spain then it is beaten for ever as a world force . . . For us we will be glad when it is all over. My idea of a good time is not being shot at, but is connected with growing lettuce & spring onions, & drinking beer in a country pub & playing quartets with friends.

A pub-and-allotment vision of the good life was closer to the modest utopias implicit in the Home Front war-artists’ paintings of the 1940s, and in the plans for a New Britain being thought out at the end of the war, than to tougher Continental versions of how things might be. It wasn’t just isolation that had made British art turn during World War Two to Neo-Romanticism, to tasteful, controlled abstraction, and to bleached, pretty things – lustre jugs and faded fabrics, the popular taste of the century before. It was also a desire for ordinariness and conviviality, a belief in common sense above theory, notions already evident in Green’s letter and in Orwell too. A quotation from Homage to Catalonia – a description of the working-class takeover of administrative buildings in Barcelona – ends: ‘There was much in it that I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognised it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for.’

Sometimes merely to put objects side by side makes a moral point. Here, in one case, is Franco’s flashy gold-mounted commander’s baton and in another a conductor’s baton – made of plain wood, slightly curved and tapered – that belonged to Pablo Casals. A photograph of Franco plump with the arrogance of autocracy standing in front of a row of bishops with sagging faces and black frocks straight from one of Goya’s anti-clerical drawings asks to be compared with a photograph of Casals in self-imposed exile writing what might be a letter asking for funds (this was many years after the war) for ageing Spanish exiles.

It was a war in which style could be matched to event. Picasso’s games with anatomy – at once dangerous and playful – had reached the point where he could make them a vehicle for tragedy: an appropriate response to a new kind of inhumanity. Erotic distortion and agonised screams could draw on the same topologies. Roland Penrose, who persuaded Picasso that Guernica should tour Britain raising funds for the Republican cause, owned his Weeping Woman. It is included here – not strictly a war picture, but, like Guernica, a painting which both hurts and demands to be looked at.

Art can make agony interesting, beautiful even, and ugliness striking. But utilitarian information – passport photographs, telegraphed despatches and official reports, things which have no interest in being eloquent – can make even great art seem untrustworthy as evidence. Capa’s photographs and an extract from a report by Hemingway of being attacked from the air as he was being driven along a road lined with almond blossom bring you not so much knowledge of how it was, as of what an artist could make of it. Capa and Hemingway are transforming agents as much as observers.

Capa’s cheering Republican fighters waving from a truck in Madrid and the dying soldier whose end is signalled by a rag-doll tumble – somehow more disjointed than a living fall would be – have an immediate power which makes their value as evidence almost insignificant. In fact (it has been doubted in the past) the dying man is now reckoned to be just that: he has a name, and a story which matches the account Capa gave of taking the picture. He is a known unknown soldier – his individuality co-opted to speak for all who fell.

Everything in this exhibition is shadowed by unresolved questions about what was, what was not, and what might have been. The objects by themselves can explain very little. But the mixture of memorabilia (relics in the religious sense) and paintings and sculpture (altarpieces, as it were) shows that there is profit in unresolved narratives. Photographs can fit into both categories: a snapshot is more like a relic, a studio photograph more like a picture. Capa’s reportage inhabits a no-man’s-land of multiple interpretations. The falling man was always an effective image; now that the death is known to be ‘real’ it evokes a deeper shudder. But all Capa’s pictures have the potential to make icons out of individuals.

By the style you know the man – well, sometimes anyway. A print of Franco with his ‘The war is over’ declaration illuminated in one corner manages to combine quasi-religious kitsch with a huckster’s commercial sincerity. But some of the posters show that while Modernism fought on only one side, modernistic graphics could serve Left or Right. Untroubled simplifications of image and message – generalised but not distorted beyond reason – seemed to suggest a better future in which style, not politics, publicity not art, would be the measure. This was commercial democratisation – the beginning of what has made ‘good design’ universal, the museum indistinguishable in its style from the shopping mall – and was quite distinct from the symbolic egalitarianism of the boiler suit (Lorca wore one) and the abandonment of formal syles of address (a letter home from Jack Jones begins ‘Dear Comrade’). The hopes of those who went to Spain are still there to rebuke us.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.