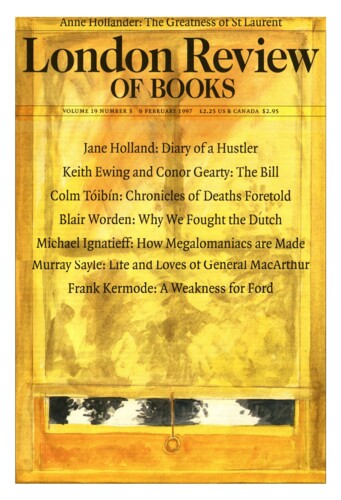

At the age of 23, never having seen a snooker table before, I picked up a cue and started practising for the Women’s World Championship. Five years later, ranked 24th in the world, I was banned for lift for bringing the game into disrepute. From start to finish, my snooker career was sheer bloody-mindedness. I had left university early to get married, had my first child and then realised I had backed myself into a corner. One night, sick of watching my husband and his friends play pool, I challenged them to a game. I beat them all, one after another. A friend took me to a local snooker club. The green baize stretched away under the hanging lamps like the pitch at Wembley, full of strange promise. The competitive edge I thought I’d lost in the haze of motherhood came back. Someone mentioned money. I picked up a cue and played as though my life depended on it.

In snooker, only two things matter: technique and bottle. The first I picked up fairly quickly, the second still escapes me, the quality that means you can pot the last black without it rattling, and keep the cue arm steady even when the wrist is weak. It is un-learnable, you either have it or you don’t. Technique can make up for it: hit the ball often enough and it will go down even under pressure. So each day, for five years, I went to the club: six hours a day at the table seemed a small price to pay for that last glorious black.

The ‘line-up’ is the most useful routine for a new player: line the balls up as in a shooting-gallery and pot them – red, colour, red, colour. If you move another ball, or fail to pot the next ball on, you start again from scratch. It sounds easy enough, but frustration makes it hard to master. In those early days, I had no coach, and no top players to watch. I spent every evening of the Embassy World Championship glued to the telly. I ransacked bookshops for manuals on technique, read them until they fell apart.

What separates professionals from amateurs is the way they hit the white. Most club players can get spin on it, to control its movement, but few can use it successfully every time. ‘Spinning’ the ball means exactly that: after the white makes contact with the object ball, it spins backwards, forwards or sideways. ‘Screwing’ the ball means putting backwards spin on it; ‘top-spin’ sends it further forward than it would naturally go; while left and right-hand ‘side’ alter its direction after contact with the object ball or a cushion rail. Side-spin becomes complicated when you are playing against the nap of the cloth: left-hand spin will send the white to the right, and vice versa. You can use any of these spin shots on their own, or in combination, or simply play without spin. But when spin is used, the cue must be parallel to the cloth at all times, even when screwing the white backwards, which is the most demanding of the spin shots. Imagine the ball as a clock-face: top spin is 12 o’clock, top and left is ten o’clock, left-hand spin is nine o’clock, ‘stun’ and left is eight o’clock, screw and left is seven o’clock. Screw-back (or ‘bottom’) is six o’clock. You reverse this for right-hand spin. But the cue must come at the ball on a straight line, and for this, your stance must be correct. Approach the table head-on, holding the cue like a club. If you are right-handed, the right leg will take the strain as you bend. The left foot should point in the direction of your shot. Keeping as low as possible reduces the possibility of movement. The cue arm should glide freely back and forth, rather like a pendulum, but only the forearm should move; the bridge-hand is spread rigid on the cloth like a starfish; your eyes should be on the white ball at all times. These techniques involve hours of back-breaking practice. Matchsticks placed on the table in ladder formation teach you to gauge the length of a screw-back; deliberately putting the white in-off develops control of top spin and side.

The first club I went to was a judo and squash club, with a few second-hand snooker tables out the back. In return for my afternoon stint, I came in each morning to brush and iron the tables. The nap of the cloth is like the fur on a cat’s neck: brush it the wrong way, and the balls skitter all over the place; brush it correctly and the table speed improves. The table iron is square and weighs a ton – my arms ached for hours afterwards. You test the iron with a wet finger before letting it touch the cloth, or you end up scorching long dark lines into the baize which make the table look like a mown bowling-green. Once I’d washed the green pelt off my hands, I could settle down to several hours of solo practice. Although the cloths were reasonable at that club, the cushion rubbers were dead, but I gradually learnt to adjust to the bad bounce. ‘Reading’ the table – knowing where the cloth is worn down to such a fine sheen that the ball skids over it like a runaway, or where a middle pocket has been cut against the bias so that a slow ball hovers over it but never drops – is a skill that takes years to perfect. Even top players come across match cloths which either run like racehorses or drag all the spin out of a ball. It’s a fine line, the perfect cloth, the perfect table.

The squash-club owner probably thought I was mad. She would watch me through the glass door, shaking her head as I set the same shot up again and again. But it worked. I rose from 90th to 50th on the ladies’ world circuit in only six months, although I had yet to be accepted by the local men as a bona fide player, not just a freak. Some all-male clubs refused me entry. Even when I found a league team willing to take me on, they would make me wait outside, like a naughty schoolgirl, while the team reserve took my place at the table. I could have stayed at home those nights, but I didn’t want to give them the satisfaction of thinking I could be got rid of. So most Tuesday nights that winter, I struggled out to some small backstreet club, to play for my team. I don’t know who was the more scared, myself or the men I played against. Every time I potted a ball my opponent went to pieces, not helped by the taunts of his own team mates. I won most of my games simply by being the first female in the league.

My game improved with my visits to world-ranking events. I became calmer at the table, playing tactically instead of smashing in absurd long pots. Most league-players just hit and hoped: I needed to go beyond that if I was to win every time. Eventually I was awarded a travelling grant from the Isle of Man Sports Council. Thanks to that I could play in world events more often, and I could stop cleaning the tables in return for my practice-time. I graduated to a bigger club, and started playing against the men in open competition. Things have changed over the past five years, but at that time a woman player in a snooker club had the same effect as a visit from the bailiffs: men ran for cover.

This particular club opened at midday. I would drift over at lunch-time. Around teatime the working men clocked off and would come into the club for a game. It was here that I first learnt to hustle. Being a woman makes it ten times harder to be convincing, but when you win, it’s twenty times worse for the victim. Soon, the regulars refused to play me. But whenever someone new walked in, which they did quite often, they would pull themselves up like John Wayne at the sight of my cue, saying: ‘I’ll show you how it’s done, sweetheart!’ Fatal last words. The trick is to appeal to their protective nature. Respot the colours wrongly, snooker yourself, even miss the ball altogether: they get all misty-eyed and pat you on the head, which is when you move in and take them for every penny. As Paul Newman said, ‘money won is twice as sweet as money earned.’

Winning a game of snooker is not particularly straightforward, especially if you’re afraid of your opponent. A difficult draw can be costly in the opening rounds, when you’re still nervous and the cue arm refuses to function smoothly. It’s vital to block out fear and focus your attention on the baize. One trick is to look at a distant light for a few seconds before looking back at the table. This concentrates the mind. An opponent who thinks you’re totally un-bothered by the error you’ve just made is likely to hand the advantage straight back to you. In one quarter-final, I left the last black over a pocket three times before potting it. My opponent was fazed by the fact that I kept looking at my watch, as if bored that I had not yet taken the match.

Snooker is a highly competitive sport; before long, even my friends were my rivals on the table. I won every local ladies’ tournament for four years and continued to beat the men regularly. For that reason alone, I was not popular. I started to suffer very badly from nerves – not during matches, but when practising alone at the club. The shadows in die club thickened. When you get a reputation for being unbeatable, even at a local level, suddenly everyone’s gunning for you. To survive, you have to keep improving. I entered every ladies’ world-ranking event and battled my way into the top 40, then the top 30, determined to get a place in the top ten. The first time I played Allison Fisher, now seven-times world champion, I was heavily pregnant with my second child. My feet were aching, and she suggested I slip my shoes off for the rest of the match. It was in the early rounds, and none of the referees seemed to notice, so barefoot and pregnant I played the World Champion. Needless to say, she won. The camaraderie of the world circuit was a relief after the hostility of my home club. Between matches, competitors play cards or nip off to other local clubs, putting in vital last-minute practice. And with all the tension, practical jokes abound. Lisa Quick (now a top-five player) bet me I wouldn’t turn up at a tournament wearing a wig. I got the most outrageous one I could find and played the entire tournament wearing it. Dress-code on the circuit is extremely strict: you can be disqualified for wearing anything other than dress trousers and a smart blouse; bow-ties are encouraged but not obligatory. There’s nothing in the rules about wigs: I won the bet but received a warning from the Tournament Controller.

Unfortunately, my politics were not as strong as my snooker. In 1990, when I realised how few women played snooker locally, I founded a Ladies’ Association to encourage more of them into the game. We ran it as a break-away group from the local governing body, which had never been interested in promoting the ladies’ game. By 1994, we were a small but thriving association with reasonable sponsorship. The governing body suddenly decided that we should come under their jurisdiction. There were rumours that they intended to persuade our committee to hand over the reins, and allegations that threats had been made to withdraw the ladies’ teams from future international events. In spite of my advice to sit tight and investigate these allegations, the ladies’ committee voted to approach the governing body with a view to affiliation. I could see our hard-won independence crumbling. I resigned as president of the Ladies’ Association and the local papers took up the story. My allegations of misconduct on the part of the governing body made the front page for several weeks; and the long and the short of it was a brief disciplinary hearing by the governing body, and another by the ladies’ committee, after which both our Secretary and I were banned indefinitely.

This was only a local ban. I could have moved to England to play, and did in fact continue playing on the world circuit for another year. But with the ban, I also lost my grant. It became almost impossible to play. I ended up practising on a table in an isolated country hotel. Without regular games against the top players, I found myself slipping. I started losing matches I should have won, and making mistakes under pressure. In 1995, I decided to retire. For five years, snooker had been my life. Suddenly, all that stopped. I rarely play now. Occasionally, when travelling, I knock the balls around on a hotel table, but that’s as far as it goes. It troubles me to miss an easy black and find myself remembering the player I used to be.

I started to write poetry instead. Playing snooker had given me a disciplined approach to routine. I write for eight hours a day, read other poets voraciously, study their technique and relate it to my own. It may seem a bizarre career change, but to my mind it’s simply a matter of getting on a different bicycle and finishing the same race.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.