A year ago, made tame by viral invasion, I wandered listlessly through the arctic wilderness of the Stonebridge Estate in Haggerston, in the company of a strategically-bearded photographer sent by this journal He had recently returned from a sharp-eyed raid on Eastern Europe and was enjoying the sense of recognition, the familiar after-images, triggered by these survivals. In a dream, the cancelled estates of Hackney were seamlessly twinned with some Stalinist wonderland. He couldn’t miss. He could point his Leica in any direction. A rough, snot-ice cladding had transformed the tenement hulks into a Gaudi cathedral: Pentonville draped in a septic wedding dress. It was the last of times. Elegantly patterned prints from the soles of our boots would soon be eradicated by the caterpillar tracks of bulldozers. Rivulets from burst pipes, clinking lianas, muted the defiant calligraphy that defaced these walls. Monster slogans in braille aimed at the wilfully blind. Demands. Complaints. Curses. This was not the work of a coven of Class War anarchists but the frantic message-in-a-bottle charter of humans at the end of their tether: marooned exiles who had nothing left beyond a collaboration with the masonry that held them prisoner. The message the dwellings tapped out was simple: ‘tear us down.’ The white lettering was a suicide note.

The photographer found a window slit in which to execute my ringing head in a cage of stalactites. I perched on tiptoe above the shifting slithering carpet of a flooded khazi that some trainee heritage pirate had tried to chisel free of its moorings. Then got the hell out. Home. Past the squatted shell of the Black Bull with its ‘No Evictions’ banner, through the Blank Generation extras waiting for nothing in the boarded-up shopping precinct, ducking into Muggers’ Alley alongside the decommissioned post office. To my Mid-Victorian terrace, an enclave of class criminals: infant teachers, retired delivery men, art historians and other assorted chancers who had invaded the borough over the last quarter of a century. And who were now clearly in a state of pre-traumatic shock as they waited for an unnecessary valentine from the local Class War cadre. ‘Unnecessary’ because many of these twitchy fly-by-nights were already desperate to get out. If only that were possible. The street was a Dunsinane of estate agents’ placards. Domestic tranquillity ravished by the repeated tithes of crack raiders with a bad video habit. We had listened obediently to divisive ‘them and us’ diatribes so many times before. ‘I work my arse off every day, because of ... scum like them. The sooner we make these bastards fuck off out of our area the better.’ The tired phrases playback in loops of hate. Once they were given an apocalyptic spin by Enoch Powell, and now they are smoothed by the in-flight rhetoric of hatchet-headed Essex men. The original keyholders of these terraces parroted the same sentiments, word for word, before decamping to the fringes of Epping Forest. An incoming tide of ‘coloureds’, group-purchasing multiple occupiers, was making it impossible for genuine white pie ‘n’ mash Hackney folk to acquire property.

It was on the Stonebridge Estate, six years ago, that a woman was discovered keeping company with the skeleton of her brother, who had been, in the words of Russ Lawrence of the Hackney Gazette, ‘propped up in an armchair’. She had conducted her life with the decaying corpse for six months, transfixed in a ghastly conversation piece, unremarked by the mundane world that surrounded her. Now, in December 1991, the woman, Hilda Kietel, made her second front-page appearance in the neighbourhood fright-sheet. She was found lying naked, except for a shawl tugged about her shoulders, under a kitchen table. She had been there for about a month. An inspection of the premises revealed no carpet, no linoleum, no cooker, no cup, no plate, no spoon. The cupboards were bare. She had been without heat or light for nearly three years. The gas supply had been disconnected at her own request. She made no reply to numerous letters form the Electricity Board. Circulars offering easy-payment schemes and coloured brochures touting the latest hi-tech innovations were messages from an alien universe.

The solitary death of Hilda Kietel could command enough bleak pathos to earn 350 words in a quiet week bereft of shotgun minuets, serial dismemberments, child-devouring canines: a week with no rival fillers beyond the defacement of the memorial to a murdered policeman in Pownall Road. An incident to delight the sub-editors of Class War who can never find enough ‘battered bobby’ pinups for their alternative page three. These vignettes of poverty, madness and despair flicker disconcertingly through the centuries. Quaker brewmasters, muscular Christians from the universities, predatory novelists trawling for copy have compiled almanacs of horror in which the same gothic motifs recur: burnt floorboards, rat-gnawed remains, guttering candles. A gloomy thunderhead of undirected blame hangs accusingly over certain districts of East London like a perpetual peasouper of melancholy statistics. The Nemesis of Neglect drifts through the courtyards with an upraised dagger. It’s all the fault of the rich, the Jews, the Masons, property speculators, some nominated other. The challenge for the authors of Class War: A Decade of Disorder, as self-appointed bailiffs of a vanishing tribe, is to publish something more meaningful than a cover version of the rancid tabloids they so obviously model themselves upon.

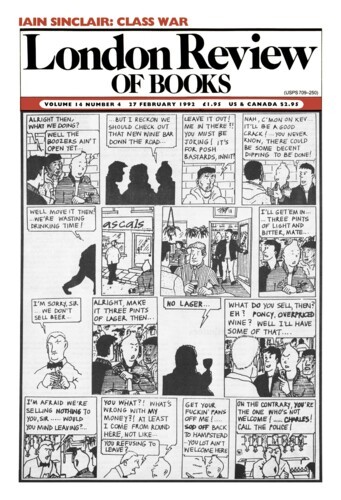

It is perhaps worth making it clear that Class War came into being as a loose federation of urban counter-terrorists, exegetes of riot, at about the time when the class whose anguish they unilaterally exploited was busy voting Margaret Thatcher, madonna of bother, into everlasting power. In brisk response to market forces, the movement began to publish and distribute a paper under the same Class War label. These propaganda sheets, as is the way of the world, were then collected in more durable form, as a book to delight the middle-class readership they so stridently denounced. The problem with such rapid knock-on success is the need to formulate a viable political programme. Could they offer anything more enlightened than a boot in the ribs, a brick through the window? Or should the exhausted city, as depicted on the wrapper of this book, be razed to the ground behind the heroic salute of the last bare-chested poll tax samurai?

Fire-watchers. Flame freaks. Black air groupies. ‘Burn, baby, burn.’ The dialectic is of secondary interest to the class warrior, who is, before anything else, an arsonist, a connoisseur of incendiary icons. These pages are so much kindling. They stink of siphoned gasoline. Upturned panda cars blaze. Office windows explode, releasing angry fists of smoke. In degraded photo-reproduction jagged white spurts of petrol-bombs orgasm among the pebbled bone helmets of snatch-squads. The mob awaits its impresario. Some shockheaded Struwwelpeter. A Malcolm McLaren whispering of historical precedents: Tyburn, the Gordon riots, Newgate ablaze, ‘Dickensian’ revengers pouring out of the slums and rookeries. It could catch on. It could be the next buzz.

What was being declared here was not so much a class war as a style war. The era of the mob was announced by bursts of pastiched lettrism, situationist raps cooked in metholated spirits, and collages of ransom demands hacked from outdated headlines. The emblems of defiance – nooses, rubber masks, pirate flags – could have been translated directly from the pages of Richmal Crompton’s Williams the Lawless, hinting at safe nursery havens lurking in the undisclosed backgrounds of some of these class warriors.

Verso have performed a dubious service by packaging these petulant yelps like the latest punk revival pressing. They have granted an unrequired status to texts whose only virtue lies in an ephemeral throwaway vitality. Something smells bad about tarting up dedications to ‘ram-raiders and rioters’ for a promotional pyramid in the window of Waterstones, Charing Cross Road. There is a very peculiar generosity in sponsoring writers who consistently jeer at the weary political pretensions of the hand that feeds them – and who blasphemously reverse the captions on side-by-side portraits of Mickey Mouse and Leon Trotsky. Class War deservedly takes its place as the Poverty Row riposte to Greil Marcus’s Lipstick Traces and Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming. This is Verso’s shot at becoming style pundits, culture brokers after the debased fashion of Faber.

Stranger fates are on the horizon. Dodge the bemused convoy of Euro-trippers clogging up the pavement, ignore the cut-price leather jacket sales, and slip into one of the satellite hotels that shelter around Russell Square. You will encounter two of the least happily married words in the English language: Book Fair. If you have the bottle, you can penetrate embattled stacks of used books, where you may be effortlessly insulted by a sodality of even more used bookdealers, none of whom will lift their eyes from their chessboards or cadged newspapers. These places have become the clearing house for exhausted libertarian and ‘counterculture’ dreck. Soft porn psychedelia has been teased into prophylactic envelopes to tempt over-stimulated gentlemen of a certain age: terminal nostalgics with interesting waistcoats and an anachronistic taste for roll-ups. They are the foot soldiers from the Sixties, the ones who were there and do remember it. Now, as trembling-fingered decadents of the Nineties, they are briskly elbowed aside by a fiercer sisterhood who prey upon Rupert the Bear, Felix the Cat and a whole wretched menagerie of juvenile fetishes. And this inevitably will be the final stand for the Class War papers. It takes 20 years for stapled samizdat effusions that everybody has and nobody wants to become prized rarities that nobody has and everybody wants. Time enough for the original prophets and gladiators to die. Commodity capitalists will already be stuffing first editions of these tattered hate sheets into storage jars as cheap futures, no-risk investments. Verso’s gathering will provide a useful sourcebook for bibliographers and nervous collectors. Bounty-hunting runners are combing the jumbles for copies of Sniffin Glue, and it will not be long before Class War becomes the thing that it most despises – a middle-class item of exchange, a document framed for display alongside concrete poems and Debord pamphlets. It’s always sad to swop a prison record for an auction record, but the law states: whenever a movement from the streets makes it into the London Review of Books, it is over. It has announced its own dissolution.

Perhaps I exaggerate. Things may not turn out to be as grim as that. The propensities of the Class War leader writers lean more towards the Beano or Dandy than the tiresome headbutting of French art guerrillas. ‘Bash the Toffs.’ ‘Let your goat into their prize rose garden.’ ‘Kidnap their snotty kids.’ The stratagems are familiar to anyone brought up on the antics of Lord Snooty and his pals, while the topics under discussion rarely deviate from the profoundly conservative programme established by the other tabloids: The Queen Mum (‘God Bless You ... Your Husband Rots In Hell’), the Duchess of York (‘Fergie Foals Again ... I Only Hope That Both Mother And Baby Die In Childbirth’), horoscopes, Vinny ‘Nutsgrabber’ Jones. Even the infamous ‘GOTCHA!’ is dusted down to celebrate the sinking of the poll tax flagship.

However subversive their aims, however extreme their sentiments, the copywriters of Class War, committed to the task of selling mob violence as the solution to ‘a decade of disorder’, were forced to compete with the more potent brand offered by Lady Thatcher and her acolytes. Punch-ups with council officials in London Fields, however satisfying, could hardly match government-sanctioned political assassinations in Gibraltar, or aerial ram-raids over Libya. They could never go far enough. They could only react, posthumously, to the radical dismemberment of the class they claimed to represent: a working class denied work and offered instead a mess of worthless shares. A working class that was fast becoming a disenfranchised underclass, the visible consequences of a return to Victorian values. They were amateurs of apocalypse, spitting in outrage at all the wrong targets. Estate agents and wine-bars were a sideshow. Attacking yuppies was like blaming sheep for the existence of slaughterhouses. Whole orders of people vanished from the agenda. Council-house tenants became temporary property dealers, manoeuvrable statistics, manoeuvring themselves into overcrowded bed-and-breakfast joints. The bloodiest battles were cynically provoked from above. And the class warriors obliged, scapegoats, innocent as scarecrows. Chaos was not the child of anarchists, but the secret state’s way of crushing both the mob and the concept of society, opening the gates to unmuzzled greed. Looking back on that mercifully remote decade, the Eighties, with its mabinogion of paranoid fantasies, it is difficult not to interpret Class War as a classic Thatcherite phenomenon. Surely these customised scruffs had to be the invention of some pinstripe think tank, a black propaganda scam?

This ‘evil bunch of foul-mouthed rebels’, as the Sunday People characterises them in a quote featured on the cover of the Verso anthology, are such convenient hobgoblins, They are identikit aliens cooked up to put the frighteners on virgin Tory voters, about to take their first punt on the stock exchange. You can almost see the strings. Watch their lips and guess at the composition of the steering committee of advertising men and control freaks who doctored the script. The pages of Class War have been planted with a very weird agenda that elbows the boring stuff about schools and hospitals, to engage with the eternal English verities – like Henley (‘knock their boaters off’), yuppies on the village green (‘get the local morris dancers to practise outside their house every Sunday morning’), and the architect’s friend, Charles, the future ex-monarch, talking to ‘loony philosophers and plants’. These jeremiads read suspiciously as if they were cobbled together by a late-night cabal of junk journalists ghosting a ‘worst case’ scenario for a passed-over Indian Army major. And yet, even in times so pinched that the supergrasses are all tax exiles, Class War must be worth more than the sweeteners with which the CIA used to keep Encounter afloat.

What is lacking in the itemised hit-list of Class War targets – BMWs, wine-bars, ‘posh housing developments’ – is any sense of an inhabited geography. The poverty that is so remorselessly exposed is the poverty of the imagination. The moral universe laid before us is as unreal as a Monopoly board. Top hats, toy cars and silver shoes are reflections of multiple images glimpsed on silent television-sets in shop windows. Nothing is observed at first hand. Nothing is touched or tasted.

It is a salutary lesson to run ‘Why We Hate Yuppies: Hackney’ against the scrupulous accuracy, the wonderfully precise physical movement, in Alexander Baron’s novel from 1963, The Lowlife. Baron, with a sense of possession earned by experience, re-creates the boarding-houses, bus routes, dog tracks, and streets down which it is still possible to navigate. He was here. He remains here. Pieces of his story feed back to us from the shop signs, the markets, the path across Hackney Downs. His eruptions of violence are scored like mechanical ballets. His argument commands respect: every shift can be tried and tested. The eradicated landscape of Hackney and Whitechapel does not need to be built again, like Joyce’s Dublin, with these novels as a blueprint. As long as the novels survive, the past survives. We brush against it, breathe it, inhabit it as a vital constituent of the present. The Class War manifestos would gain, in urgency and wit, from being left where they belong on the railway-bridges and sweatshop walls. An honourable treaty with place might then be struck.

You cannot bring down an invented city, populated by cut-out symbols of oppression. Where are these phantom wine-bars? As Patrick Wright points out in A Journey through Ruins, it is a brutal ‘half-hour hike’ from the Bow Quarter fortress for anyone thirsty enough to trade life and shoulder-bag for a lime meniscus in their Mexican beer. Wine-bars in the neighbourhood of Kingsland Waste, even as blatantly conspicuous fronts for the laundering of funny money, have an unmatched record of failure. A few notably surreal evenings were on offer before they were drowned in a slurry of breakfast-bars, burger palaces and multi-ethnic speed-cuisine bikers.

Now is the hour to grant a truce to the derided yuppies, to see them plain as social visionaries, the premature colonists of a brave new world. How bravely they broke the ground, pushing, like the wagon-trains of old, into an unconquered wilderness. They risked everything, only to find themselves trapped for the duration. The unthinkable happened. The market died. Promises of ‘Little Apple’ loft-living were revealed as life-sentences in the South Bronx. Gluttony devoured its own entrails, vomiting up blood, bile and water. Under-subscribed architectural follies on the Isle of Dogs were obliged to meet their survival quotas by enrolling ‘problem’ families, outpatients, and dismissed legions of the mad. Empty palazzi, dazzling in reproduction, had to be leased to Baltic trade missions until they could claim their place in the order of things as the new Hong Kong, dukedom of the swamps.

History is movement. But Class War is determined to enforce perpetual stagnation by insisting that certain districts belong only to certain classes. This Monopoly-board mapping is even-handed: it patronises everybody. It refuses to recognise that the yuppies are immigrants. The retrieved remnants, the odd hank of ruched curtain, or shattered cellphone, of these Stock Exchange Romanies will be featured in the Princelet Street Heritage Centre with artifacts left by the Huguenots, Bengalis and Jews. The filofax will lie in peace alongside the weaver’s bobbin.

Class War describes that inevitable arc from rage to retaliation: it mutated into a political party. A conference was summoned in Shoreditch Town Hall. It was well attended by the usual skulking crush of close-cropped, booted outlaws in leather jackets and tacky parkas: the press get everywhere. Their numbers were swollen for this gig by Special Branch snappers intent on clogging the files with useless mugshots. Shoreditch became an underground Maastricht, brought to life by delegates eager to debate the federalist implications of a ‘European-wide revolution’. Preparatory reading for the conference included papers on ‘Bashing the burglars’, ‘Using sisterhood like the Masons use brotherhood’, and the iniquitous price of Virago paperbacks. In the evening, as at Blackpool or Brighton, delegates let their hair down with an Elvis Presley karaoke singalong in a Green Lanes pub.

‘Where there is no future, there cannot be sin,’ screamed Johnny Rotten. The prophets of the Class War movement have seen ‘No Future’ all about them, and have been drawn irresistibly into its force-field as into a black hole. They have built their doctrine upon nothing, horizontal dereliction, year zero ruins. Perhaps we are at the end of things, incapable of imagining a better way. If the coming decades deliver nothing more potent than revenge, riot and convulsion, Class War will be hailed as the most perceptive analysis of what is on offer. Then God help us.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.