In Madrid the other week a literary journalist told me the following joke. A man goes into a pet shop and sees three parrots side by side, priced at $1000, $2000 and $3000. ‘Why does that parrot cost $1000?’ he asks the owner. ‘Because it can recite the whole of the Bible in Spanish,’ comes the reply. ‘And why does that one cost $2000?’ ‘Because it can recite the whole of the Bible in English and in Spanish.’ ‘And the one that costs $3000, what does he recite?’ ‘Oh, he doesn’t say a word,’ explains the pet shop owner: ‘but the other two call him Maestro.’

This made me think, naturally enough, of E.M. Forster; and then of the fact that we were about to undergo the annual garrulity of the Booker Prize for Fiction. Would Forster have won the Booker? In 1905, when he published Where angels fear to tread, he would have been up against Kipps, not to mention more populist contenders like The Scarlet Pimpernel and Mrs Humphry Ward’s The Marriage of William Ashe. In 1910 Howards End might have run into Clayhanger, and (Wells again) The History of Mr Polly; perhaps the Antipodean outsider Henry Handel Richardson would have scooped it with The Getting of Wisdom. In 1924 Forster’s publishers might have thought they had a chance with his block-buster, A Passage to India. For once, Wells wasn’t dogging him: but there was Maurice Baring’s C, Ford’s Some do not, Masefield’s Sard Harker, Mottram’s The Spanish Farm, plus various dangerous floaters like The Constant Nymph, The Inimitable Jeeves and even (if it was to be a year for the booksellers) Mary Webb’s Precious Bane.

Still, the mistake, then as now, is to look at the books themselves. When literary editors pen those overnight pieces on the Booker short-list and lament the omissions – where was McEwan? Where was Boyd? Where was Amis? And the other Amis? – they are examining the candidates (not all of whom they can possibly have read) rather than the judges. If I were Mr Ron Pollard of Ladbrokes (whose odds have got a great deal meaner since the days when some of us cleaned up on Salman Rushdie at 14-1), I would give only cursory attention to the books on the short-list: instead I would study the psychology and qualifications of the judges. And it does take all sorts. Three years ago, when I was short-listed for my novel Flaubert’s Parrot, I was introduced after the ceremony to one of the judges, who said to me: ‘I hadn’t even heard of this fellow Flaubert before I read your book. But afterwards I sent out for all his novels in paperback.’ This comment provoked mixed feelings. Still, perhaps there are judges of the Turner Prize who have never heard of – let alone seen a painting by – Ingres.

So how did the judges do this year? Well, let us begin by congratulating them: for having chosen a serious book by a serious novelist; for behaving, mostly, with propriety; and for having turned up to the dinner. These seem pale compliments? They aren’t in Booker terms. Previously, some notably minor and incompetent novels have gained the prize; judges, inflated by their brief celebrity, have competed like kiss-and-tell memoirists to spill all to the radio and newspapers; while two years ago one of the judges didn’t even make it to the judicial retiring-room. Joanna Lumley, already burdened with the annual ‘non-reader’ tag, understandably maintained her sense of priorities by playing a South Coast matinée rather than wrangle with literati over the competing merits of Iris Murdoch, Jan Morris and Keri Hulme.

This year the judges did make one interesting – and perhaps influential – early decision. Publishers have hitherto been allowed to nominate four books for the prize, but also submit a ‘B’ list which the judges can call in if tempted. This year the ‘A’-list allowance was reduced from four to three, thus putting greater pressure on those publishers (not many, it has to be said) who issue more than three worthwhile novels a year. Some of these publishers – most notably Mr Tom Maschler of Cape – have for a few years legitimately exploited the two-list process by occasionally putting solidly established novelists on their ‘B’ list (knowing there was a high chance of such books being called in) while risking more left-field items in the ‘A’. This year – to take one interpretation of events – the judges decided to call the publishers’ bluff. No ‘B’-list books at all were considered, and devious publishers were thus outwitted. There is, however, another interpretation: that the judges hoofed the ball into their own net. What they were in effect saying was this: we’ll go along with what the publishers propose, we’re sure they can judge a novel just as well if not better than us. So let’s dutifully plough through these three bodice-rippers from Rudland and Stubbs, but call in Anita Brookner or Nadine Gordimer? No, no, we won’t do that, even if they have won the prize before. More than an abnegation of responsibility, this displayed a singular lack of curiosity. And while the judges annually complain about the great burden of reading placed upon them, it must be the case that most of the hundred or so novels submitted can be discarded pretty quickly. I was going to say after twenty pages, until I remembered the case of a Booker judge a few years ago who was doing some early winnowing on a train and lofted one contender out into the passing prairie after no more than twenty pages. A couple of months later the judge wryly stuck to the doctrine of collective responsibility as the cow-fed fiction hoisted the big cheque.

The Booker, after 19 years, is beginning to drive people mad. It drives publishers mad with hope, booksellers mad with greed, judges mad with power, winners mad with pride, and losers (the unsuccessful short-listees plus every other novelist in the country) mad with envy and disappointment. The dinner itself is a painful experience for five out of the six writers, made worse by the fact that four weeks’ expectation (during which no regular work can be done) usually produces some psychosomatic malady – a throbbing boil, a burning wire of neuralgia, the prod of gout. The only tip I can give future short-listed candidates is how to work out just in time that you haven’t won. While the writers themselves never know the winner’s identity in advance, various people in the hall do, including the TV technicians. You could ask them directly, of course (or bribe the judges’ chauffeur, who is always a good source): but you will find out surely enough whether you have landed the big pot by following the movements of the hand-held camera on the Guildhall floor. Ten or fifteen seconds before the announcement is made it will head towards you – or, more probably, head towards someone else. This will give you time in which to prepare a generous smile, a quietly amused eyebrow or a scornful nostril.

How should novelists get the whole event in some sane perspective? They cannot retreat into a grand carelessness until they are John le Carré or John Fowles. They might begin, however, by running through the list of previous winners and working out how many of the last 19 would feature in any ‘true’ list of Top 19 Novels 1969-87. They might observe that ‘Booker’ – a jaunty if hardly necessary shortening – is increasingly an affair of the book trade rather than a pointer to the state of fiction: thus a ‘good’ winner, in Booker parlance, is a novel that the bookshops can shift. They can further reflect that whereas in 1972 the three judges were Cyril Connolly, George Steiner and Elizabeth Bowen, in 1987 a television newscaster, by virtue of having written a biography of Viv Richards, was at least more ‘literary’ than one of the other judges. And then the novelists had better conclude that the only sensible attitude to the Booker is to treat it as posh bingo. It is El Gordo, the Fat One, the sudden jackpot that enriches some plodding Andalusian muleteer.

The Booker Prize is worthy in that it normally goes to a serious novel, seriously intended and seriously judged, and that the money helps a usually underfunded novelist. It’s dubious because it now has an unwarranted influence on public perception of the novel; because if it continues to increase in power it may well end up Thatcherishly producing two nations of novelists; and because it distracts novelists from their novels (it’s hard to realise, after the caravan has passed, that your book is just as good or just as bad as it was before it made the baggage-camel or not). At least so far, there’s been no evidence of novelists ‘Bookerising’ their work to please the judges. Have there been certain items of fiction in recent years which seemed to have been using steroids? Yes indeed: but long before the Booker Prize existed writers were trying, as Ron Pickering has it, to pull out the big one.

In any case, pulling out the big one might not necessarily work. Sometimes the judges prefer you to pull out the small one. In France, on the other hand, prize novels are more likely to be successfully written to a formula. Over there, members of literary juries continue remorselessly in power until their ink dries; some judges double as literary advisers in publishing houses; and there exists an almost openly cynical attitude of ‘Whose turn is it this year?’ (the turn being the publisher’s rather than the writer’s). Nothing astonishes French journalists more than to be told that on the major British literary prizes the judges are replaced regularly, if not annually. C’est le fair-play anglais, they comment admiringly.

A year or so after missing out on El Gordo, I managed to land le tiercé in Paris: the Prix Médicis. The ceremony proves a little different from the affair at Guildhall. There is an announcement – at which the winner is not present; followed by a lunch – which the winner does not eat. Instead, you wait in a bar across the road from the bulging Beaux-Arts building where the judges are assembled, and try to pretend you don’t already know you’ve won; a runner comes from your publisher to break the ‘news’; you cross the road into a swirl of journalists who have heard the announcement you have missed; then you search for your jury to thank them. My publisher and I tentatively entered a large dining-room where a dozen literati were all well into their lunch. C’est Monsieur Barnes, she announced, but not a single fork paused on its way to a single mouth. Oh dear, I thought, I was obviously some terrible compromise candidate; I shall be the Keri Hulme of the Prix Médicis. But no, we’d disturbed the jurors of the Prix Fémina by mistake. So on to another dining-room, and another dozen lunchers: C’est Monsieur Barnes. This time forks paused, and chairs were scraped back: though not even a congratulatory glass of Badoit came my way. A day or so later, the President of the jury asked how I wanted my prize (humble by Booker standards – about £450). I took his personal cheque. My bank refused it; I sent it back to them; again they returned it; I sent it back to them again. Finally, they explained: ‘Not only can we not honour this cheque, but we suspect that the person who wrote it might be trying to evade exchange-control regulations.’

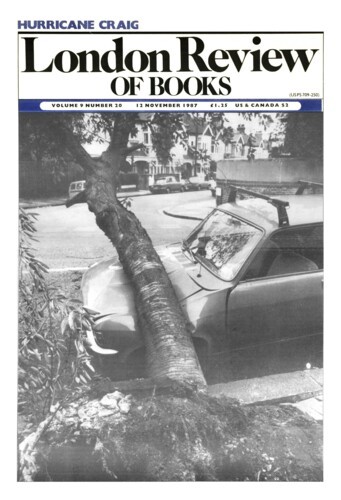

The couple of weeks before this year’s Booker announcement contained some violent distractions for fretting shortlistees: the pseudo-Crash, which gave those uncharmed by the Tell-Sid society some quiet schadenfreude; plus the far fiercer and more melancholy events of the Hurricane. When a great storm ravaged Normandy in 1853, destroying gardens and greenhouses, Flaubert took stony pleasure in this reminder that Nature was not there for our convenience: ‘People believe a little too easily that the function of the sun is to help the cabbages along.’ But for us there was little comfort along these lines: the nation was too busy roasting poor Mr Fish the weatherman (when did we believe him anyway?) to learn wider lessons; and besides, the damage, as moral instruction, was way into overkill.

At least the Hurricane didn’t have one of those cosy Christian names attached to it, as it would have done in the States. We were spared the notion of Hurricane Kevin or Hurricane Sabrina, with people first-naming disaster. ‘Did you see what that Craig did to the back fence?’ One thought it provoked rather adventitiously was about the Booker Prize. Perhaps, after getting down to the short-list, the organisers should admit the bingo aspect of the whole event and decide the winner on some random yet practical basis. This year, for instance, it might have been awarded to whoever suffered most in the Hurricane. Did Iris Murdoch lose some elms? Does Peter Ackroyd’s cottage need re-thatching? The expatriate Brian Moore might not seem to qualify for Hurricane Relief: but he lives beside the San Andreas Fault, and might soon need underpinning. In the end, of course, the judges relied on the more established but just as frivolous system of polite compromise and Moore lost out to Penelope Lively. Trevor McDonald, writing in the next morning’s Independent, revealed that ‘what decided the issue in the end was the fact that their feeling against Moore was stronger than their views about Penelope Lively.’ I’m thinking of calling my next novel The Compromise.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.