John Reed, witness to the October Revolution and author of Ten Days that Shook the World, seems to have turned against the Bolshevik leaders just before he died in Moscow in 1920. His apostasy was not publicly known, however, and a decade later the American Communist Party, eager to exploit his fame, encouraged the formation of John Reed Clubs in New York and other cities ‘to bring closer all creative workers’. The first issue of Partisan Review, which appeared in February 1934, was produced by the New York branch of the JRC. ‘Through our specific literary medium,’ the editors wrote,

we shall participate in the struggle of the workers and sincere intellectuals against imperialist war, fascism, national and racial oppression, and for the abolition of the system which breeds these evils. The defence of the Soviet Union is one of our principal tasks. We shall combat not only the decadent culture of the exploiting classes but also the debilitating liberalism which at times seeps into our writers through the pressure of class-alien forces. Nor shall we forget to keep our own house in order. We shall resist every attempt to cripple our literature by narrow-minded sectarian theories and practices.

The first issue of Partisan Review included a section from James T. Farrell’s once famous Studs Lonigan trilogy, which relates the young manhood and eventual destruction of a Catholic boy from Chicago, as well as improving tales written in would-be proletarian style. There was an attack on bourgeois literary critics and a sample of Depression poetry (‘Tonight, like every night, you see me here/Drinking my coffee slowly, absorbed, alone’). The second issue included a story called ‘The Iron Throat’, on the miseries of a Wyoming mining family. It was written by Tillie Lerner, ‘a 21-year-old Nebraska girl’, ‘who took a leave of absence from the Young Communist League to produce a future citizen of Soviet America’.

After twelve issues, two of the young editors, Philip Rahv and William Phillips, appalled by the Moscow show trials of 1936 and 1937, wrested the magazine from party control. The new PR emerged in December 1937. F.W. Dupee, Dwight Macdonald and Mary McCarthy were also on the masthead, as was George L.K. Morris, artist, art critic and moneybags for the new venture. Despite Morris’s largesse, most of the editors and all of the contributors were at first unpaid. For a young writer, however, appearing in the magazine offered recognition and social compensation – endless hard-drinking, hard-fighting parties.

The editors offered a fresh statement of purpose, doused in scorn:

The old movement [the party doctrine in literature] will continue and, to judge by present indications, it will be reinforced more and more by academicians from the universities, by yesterday’s celebrities and today’s philistines. Armed to the teeth with slogans of revolutionary prudence, its official critics will revive the petty-bourgeois tradition of gentility, and with each new tragedy on the historic level they will call the louder for a literature of good cheer.

This was a demand for intellectual toughness, for originality and force, for an end to rote position-taking and inane redemption narratives.

The lead piece in the new magazine was Delmore Schwartz’s story ‘In Dreams Begin Responsibilities’, a bitter fantasia that is about as far from socialist realism as one could imagine. It was followed by another lonely-coffee-cup lyric, but in a quite different key – Wallace Stevens’s poem ‘The Dwarf’:

Neither as mask nor as garment but as a being,

Torn from insipid summer, for the mirror of cold,

Sitting beside your lamp, there citron to nibble

And coffee dribble … Frost is in the stubble.

Then came Edmund Wilson’s essay ‘Flaubert’s Politics’, which ends with this sentence: ‘As the first big cracks begin to show in the structure of the 19th century, [Flaubert] shifts his complaint to the shortcomings of humanity, for he is unable to believe in, or even to conceive, any non-bourgeois way out.’ This was a splash of cold water in the face of PR’s communist and socialist readers – and a premonition of the young editors’ political fate. Finally, there were some barbed Picasso etchings from the series The Dream and Lie of Franco (Guernica was first shown earlier that year); and some roughhouse banter from Macdonald about the passionless ease of the old New Yorker: ‘Its editors would have considered Mark Twain too crude and Heine too highbrow for their purposes … Its inhibitions stretch from sex to the class struggle. It can be read aloud in mixed company without calling a blush to the cheek of the most virtuous banker.’

Some of the new magazine’s contributors were middle class, but an extremely ambitious cohort of undergraduates at City College, a campus of the public City University of New York, soon forced their way in. Many of them made the long subway ride from ghettoes in the Lower East Side, the Bronx or Brooklyn to the 137th Street stop on the IRT in Harlem. City College, with its marzipan-draped gothic architecture, sat at the top of a small hill above Broadway on Convent Avenue. The college was free, and open to any qualified male student; it has been estimated that its Jewish undergraduate population in the 1930s was 80 per cent (women went to Hunter, another part of CUNY). Most of the teachers were nothing special. Irving Howe remembered them as dull and overworked; they were ‘old dodos’, according to the sociologist Daniel Bell. The real action took place in the alcoves next to the cafeteria. Irving Kristol, who would move far to the right, wrote in Memoirs of a Trotskyist (1977) that there were several alcoves, ‘but the only alcoves that mattered to me were No. 1 and No. 2, the alcoves of the anti-Stalinist left and pro-Stalinist left respectively.’ Alcove No.1 ‘soon became most of what City College meant to me’.

The alcoves had the heavy, dark-stained oak tables and chairs used everywhere in the New York public school system. The young men lounged there with their feet up, but were properly dressed in jacket and tie. The consciously louche bohemian style of Greenwich Village wasn’t something they aspired to. They brought in sandwiches from home (hard-boiled egg, cream cheese, peanut butter or occasionally chicken, according to Kristol) because they couldn’t afford the cafeteria. In Alcove No. 1, the Trotskyites, Shachtmanites (a faction within the Socialist Workers Party), Social Democrats and apologetic New Deal liberals gathered, united only by their newfound loathing of Stalin and the Soviet Union. Arguments that began early in the day were sometimes still raging in the afternoon (Howe remembers leaving, going to class and returning to the same debate). The conversation was in the anxious, hammering style of students trying to master difficult texts. The point was to pull out the rug from under your opponent, to convince him that his premises were wrong.

Most of the Stalinist students in Alcove No. 2 observed party discipline and refused to speak to their neighbours. The bravest went off to fight in Spain; some of them died there. Although the majority of the students in both alcoves disappeared into middle-class American life, some were hauled out of anonymity in the McCarthy era and pilloried for such crimes as signing a petition in favour of Republican Spain or marching alongside communist union members at a rally.

Not all were so innocent. According to Kristol, one of the regulars at Alcove No. 2 was Julius Rosenberg. In the 1930s and 1940s, these students thought they were the future – not an irrational belief given the influence of the Communist Party in New York, in the unions, in publishing, in theatre and journalism, in the art world, even in broadcasting. ‘The only place where the conflict between Stalin and Trotsky could be debated freely was in New York City,’ Howe said, referring not just to the alcoves but to the city’s social scene, whose allegiances, manipulations and treacheries Mary McCarthy described with satirical (and self-satirising) play in her essay ‘My Confession’, published in Encounter in 1954.

City College’s young men were determined to escape naivety and provincialism. They did not recognise the authority of Christian tradition and had little interest in Jewish tradition, though the incomparably dramatic but morally unaccountable Hebrew Bible probably shaped their temperament more than they liked to admit. They wanted to stop sounding like their relatives; they wanted an end to softness and Yiddishkeit. They were propelled, however, by their immigrant parents’ almost maniacal faith in education. The way out of provincialism, they determined, was to absorb everything that might matter in the creation of a modern intellectual: Marx, Engels, Mill, Tolstoy, Flaubert, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Dostoevsky; Austen, Dickens, Conrad and James; Eliot, Proust, Joyce, Lawrence, Mann; Freud and the newly translated Kafka. The books might feed a sense of alienation which was rescued by arrogance. Living in an exuberant, crudely philistine business culture, they managed to create, for the first time since the Emerson circle, a critique that was neither provincial nor sentimental.

They were serious in a way that only young men and women who feel they have been tasked with determining the future could be serious. The Depression and the oft-predicted, half-longed-for collapse of capitalism in America, the rise of fascism in Europe and the convolutions of the Soviet state were an alarming and exhilarating challenge. Socialism opened the world to them, but rapture was followed by bitter disappointment. Most of the working class in America did not long for revolution; Stalinism in its American iteration was poisoning liberal thought; the fellow-travellers in the Popular Front couldn’t be trusted. The New York group dedicated itself (at least in spirit) to democratic socialism or a benevolent version of Trotskyism. In some ways they never got over their anger at the Stalinist betrayal.

The house style of the early Partisan Review was hard-headed, truculent, dismissive of religiosity (‘mystification’), academicism and ‘folk culture’, sceptical of the American weakness for self-serving sincerity and sanctimony. McCarthy’s theatre reviews could be witty and amusing, but the magazine was mostly indifferent to the frivolous. With the exception of an occasional movie (both Lionel Trilling and Norman Podhoretz engaged in cinematic cinq-à-sept), mass culture’s pleasures were hard to admit. Clement Greenberg argued in a 1939 PR essay that kitsch drew on ‘simulacra of genuine culture’. Apart from drinking a lot, the PR writers were American Jewish puritans.

After a decade, Rahv and Phillips put together an anthology called The Partisan Reader. The magazine had started with eight hundred subscribers in 1937; by 1946, it had six thousand. The cover style would last for decades: a solid box of colour enclosing the letters ‘PR’ in the upper right corner and a larger vertical rectangle of the same colour on the lower left, enclosing articles listed in order; no decoration, no emphasis, the general aspect of an old insurance company office door with its employees plainly listed. ‘Our principal interest, editorially,’ they wrote in the afterword to the anthology, ‘was in bringing about a rapprochement between the radical tradition on the one hand and the tradition of modern literature on the other – a rapprochement that virtually all left-wing magazines had in the past done their utmost to prevent.’ Their insistence on advanced new literature as part of radicalism’s strength was centrally influenced by Trotsky, whose intellectual independence and literary brilliance they admired without adhering to his programme of world revolution. In 1938 Trotsky had contributed an article from exile in Mexico. ‘Art, like science, not only does not seek orders, but by its very essence, cannot tolerate them … Truly intellectual creation is incompatible with lies, hypocrisy and the spirit of conformity.’

The joining of advanced politics and advanced art was for forty years PR’s justification and its boast. But in the early days, for all their bravado, the editors weren’t always sure what they wanted. They began with a rueful acknowledgment: the battle for acceptance of the great modern writers had been won by the previous literary generation. ‘They came late,’ Howe wrote of the PR editors in 1969. Their notion that journalistic criticism was the highest and most vital calling for a non-fiction writer wasn’t new either. At first, they struggled to find their own enthusiasms. They were tired of Hemingway, very slow to warm up to Faulkner and conventionally dismissive of Virginia Woolf. Rahv, 1943: ‘There is a crucial fault even in Mrs Woolf’s grasp of [the tradition of English poetry and of the poetic sensibility], for she comprehends it one-sidedly, and perhaps in much too feminine a fashion, not as a complete order but first and foremost as an order of sentiments.’

Rahv and his fellow editors were casually and often comprehensively chauvinist. Yet when it came to turning out a good magazine, they had to relent. Some women attracted to the magazine wrote so well that they crashed through the boys’ club indifference and scepticism. McCarthy was there at the beginning. Elizabeth Hardwick, a Southerner who moved to New York in 1939, aspiring ‘to be a Jewish New York intellectual’, began writing for the magazine in 1945. The umbrageous Diana Trilling, wife of Lionel and often at war with the others, started writing book reviews for the Nation after 1941 and lengthy moralising essays for PR in 1950. Hannah Arendt first wrote for PR in 1944, after arriving in 1941 on the Upper West Side.

Some of PR’s contributors, such as Lionel Trilling and the art historian Meyer Schapiro, were academics (they were both at Columbia); after the war, many of the others took teaching jobs. But the ideal was always the life of the freelancer – to be precise, the ideal was Edmund Wilson, fifteen or so years older, a man who lived by his wits, travelled widely, and wrote fiction, journalism, criticism. In the 1940s, an independent writing life in New York was not entirely a fantasy. If they were unmarried and indifferent to comfort, writers could live on a few thousand dollars a year. They worked in factories, taught night-school classes, took jobs in journalism; they ate in coffee shops and red-sauce Italian restaurants in the Village, drank terrible liquor at cigarette-hazed parties. In the summers, they rented a cottage in Long Island, Connecticut or on Cape Cod. The city around them, in the expanding postwar economy (GDP grew by 8.7 per cent in 1950), was awash with money. Amid the new skyscrapers many things were happening: Abstract Impressionism, bebop, George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet, Leonard Bernstein.

The PR writers were in a kind of paradise, though no one would have said so at the time. A compact group (no more than fifty over the decades), they were competitive, rude, maniacally obsessed with one another – ‘the family’, as the journalist Murray Kempton called them. They fought over the continuing relevance of ‘the left’, over their own situation as outsiders and critics, over Freud and post-Freudians, the value of Malraux and Camus and Maritain. Norman Mailer, who was both praised and roughed up by the group, described them (in PR) as ‘that peculiar colony, aviary and zoo of the most ferocious, idealistic, egotistic, narcissistic, cultivated, constipated, brilliant, sensitive, brutally insensitive, half-productive and near-sterile gang of the best and worst literary court ever to rise right out of the immigrant ranks of a nation’. The moniker ‘New York Intellectuals’ did not appear until the 1960s. To my ears it always sounded like a circus act. But it has stuck.

Were they an ‘intelligentsia’? In a Partisan Review article from 1944, Arthur Koestler attempted a general definition:

The intelligentsia in the modern sense thus first appears as that part of the nation which by its social situation not so much ‘aspires’ but is driven to independent thought, that is to a type of group behaviour which debunks the existing hierarchy of values (from which it is excluded) and at the same time tries to replace it with new values of its own.

The New York group were driven all right, but their characterisation of themselves as radical social critics now seems slightly comical. In the beginning, they had no interest in political power (that came after the war, as some of them moved far to the right). In their prime, they were a vanguard group whose most significant revolution was in American taste. In the decade after its founding, PR published poetry by T.S. Eliot (‘East Coker’ and ‘The Dry Salvages’), W.H. Auden, Wallace Stevens, Randall Jarrell, William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore and Elizabeth Bishop; fiction by Kafka (‘In the Penal Colony’), Jean Stafford and Saul Bellow; criticism by Wilson, Rahv, Trilling, Phillips, Kazin and McCarthy. As the group acknowledged, far from embracing radicalism, or even liberalism, many admired modern writers were either indifferent to political life (Joyce) or attracted to fantasies of ‘blood consciousness’ (Lawrence), Christian order (Eliot), a never-never land of Irish aristocrats and peasants (Yeats), traditional Southern society (Faulkner) or antisemitic fascist nonsense (Pound). With relief, PR published intellectuals and novelists from the European left who had lived through the beliefs and treacheries of communism – Koestler, Ignazio Silone, Czesław Miłosz; also George Orwell, never a communist, who contributed fifteen ‘London Letters’ during the war and whose memoir of his bedwetting schooldays, ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’, appeared in Partisan Review after his death.

As Howe and Trilling later admitted, the New York intellectuals did not produce a great writer from within their ranks. Lowell was the poet of Boston, Bellow a Chicago man, though he did write a short masterpiece, Seize the Day (1956), set in the refugee-haunted Upper West Side. Bernard Malamud was surpassed by Isaac Bashevis Singer, a great figure in Yiddish literature but not one of the gang. Gazing through their fingers, the group regarded Mailer warily. His friendship with Diana Trilling began well (his opening sally, which she loved: ‘And how about you, smart cunt?’), but he lost their faith with his head-butting at parties; his assault on his second wife; his fascination with boxers, murderers and spies; and his overheated sex-and-violence-Nevada-desert pop fantasia, An American Dream (1965). It was only partly restored by his later remarkable journalistic work.

They did produce great critics. The PR writers cast their literary judgments in historical terms. In his essays on Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Gogol and Chekhov (reprinted in Essays on Literature and Politics 1932-72), Rahv describes these writers not just as products of a particular historical situation but as actors in the history of consciousness. Born in Ukraine, Rahv lived in Palestine with his family for a few years, moved to the US in 1922 when he was fourteen. He never went to college but taught himself languages and literature in public libraries. After a short period as a communist, he left behind ‘the metaphysics of dialectical materialism and the messianic role assigned to the working class’, but not Marxism itself. His habits of mind remained dialectical, as when he describes the Jamesian heroine, ‘the heiress of all the ages’, who, riding the crest of American industrial power, sets herself to absorb (and to buy) the riches of Europe:

Where she excels is her capacity to plunge into experience without paying the usual Jamesian penalty for such daring – the penalty being either the loss of one’s moral balance or the recoil into a state of aggrieved innocence. She responds ‘magnificently’ to the beauty of the old-world scene even while keeping a tight hold on her native virtue: the ethical stamina, good will and inwardness of her own provincial background … In the long run she cannot escape the irony – the inner ambiguity – of her status. For her wealth is at once the primary source of her so lavishly pictured ‘greatness’ and ‘liberty’ and the source of the evil she evokes in others.

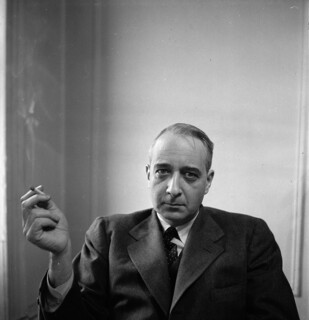

A large, burly man with a gravelly voice, Rahv was the organisational and spiritual leader of the PR writers and the dominant editor at the magazine (Phillips, quieter, kept the ship on course), an authority despite the pastrami sandwich often in his hand – no, especially with the pastrami sandwich in his hand. Academic writing on American literature around 1940 was stuffy, easy to push aside, and Rahv and Kazin, in On Native Grounds (1942), his panoramic literary and moral history of American literature from the 1890s to 1940, leaped at the opportunity.

The art critics whose work appeared in PR were also genuine powers. Meyer Schapiro’s field was Romanesque art, but he wrote with sympathy about the Impressionists, Cézanne, Seurat, as well as non-figurative artists such as Malevich and Kandinsky. Consciously or not, he became, in such essays as ‘The Nature of Abstract Art’, published in 1937 in Marxist Quarterly, the herald of a revolutionary aesthetic about to spring brilliantly to life in New York. In the 20th century, repelled by bourgeois society and industrialism, artists were retreating from representation into greater and greater abstraction. In contemptuous response to the morally fervent art of the 1930s, Greenberg insisted that subject matter or ‘content’ in art ‘should be avoided like the plague’. Art should not be bound by ideology. In a Shapiro-influenced PR piece called ‘Towards a Newer Laocoön’, published in 1940, Greenberg used Lessing’s notions about the distinctive properties of each art form to call for the proscription from painting of any element that wasn’t intrinsic to painting itself. The tone was almost jeering. ‘The history of avant-garde painting is that of a progressive surrender to the resistance of its medium; which resistance consists chiefly in the flat picture plane’s denial of efforts to “hole through” it for realistic perspectival space.’ ‘The picture plane itself grows shallower and shallower,’ he went on,

flattening out and pressing together the fictive planes of depth until they meet as one upon the real and material plane which is the actual surface of the canvas; where they lie side by side or interlocked or transparently imposed upon each other. Where the painter still tries to indicate real objects their shapes flatten and spread in the dense, two-dimensional atmosphere. A vibrating tension is set up as the objects struggle to maintain their volume against the tendency of the real picture plane to re-assert its material flatness and crush them to silhouettes.

This was written in 1940, three years before Jackson Pollock’s Mural and seven years before his drip paintings.

In 1952, Harold Rosenberg, distinguishing the New York Abstract Expressionists from other abstract artists, wrote that ‘at a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act – rather than as a space in which to reproduce, redesign, analyse or “express” an object, actual or imagined. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.’ Rosenberg’s words captured what many were trying to say. The New York critics seized on the distinctly modern element in new work: the element that not only broke with convention but moved art forwards in ways that were emotionally overpowering. This could lead to a celebration of personal mystique and then to exhaustion – Pollock’s fate. ‘Satisfied with wonders that remain safely inside the canvas,’ Rosenberg wrote, ‘the artist accepts the permanence of the commonplace and decorates it with his own daily annihilation. The result is an apocalyptic wallpaper.’ All these critics had their favourites – Rosenberg was more interested in the work of Hans Hofmann and Willem de Kooning than in Pollock – whom they tried to promote in the hard world of art galleries.

Trilling, eager to dispel liberal simplicities and right-mindedness, obsessively praised such qualities as complexity, ambiguity, nuance, contradictoriness. Those descriptive qualities adduced as values became standards of judgment for many other writers. Macdonald insisted on a classification of highbrow, middlebrow and lowbrow, a handy tool adopted not just by the New York writers, but more widely – until Susan Sontag, a bastard child of the group, torpedoed such distinctions in the 1960s.

Many people resented the New York group, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, when their influence was obvious. Several publishing houses (Farrar, Straus, Simon & Schuster, Knopf) were run by Jews and talk of conspiracy became commonplace. In The Literary Mafia: Jews, Publishing and Postwar American Literature (2022), Josh Lambert reports that Jack Kerouac, who managed to publish thirteen books in his short life, complained that ‘the Jewish literary mafia’ was holding him back. Mario Puzo also spoke of a Jewish mafia controlling award grants; perhaps, but Puzo did rather well without them. Truman Capote told Playboy in 1968 that ‘a clique of New York-oriented writers and critics … control much of the literary scene through the influence of the quarterlies and intellectual magazines. All these publications are Jewish-dominated and this particular coterie employs them to make or break writers by advancing or withholding attention.’ Some of the young writers in New York were depressed by their elders. ‘No one could have read as many books as they claim to have read,’ a friend of mine wailed fifty years ago. As far as Mailer was concerned, the fabulous literacy was a put-on. ‘No one knew as much as they claimed to know, no one could have passed through the galaxies of experience they were ready to judge.’

This hostility is understandable enough, but Ronnie Grinberg’s book, Write like a Man: Jewish Masculinity and the New York Intellectuals, has a single line of analysis – really, a single line of attack. She argues that the New York intellectuals were macho bully boys who strove to overcome their outsider status as Jews by consciously imitating the most conventionally aggressive forms of American masculine behaviour – the manner of gangsters, of Theodore Roosevelt and the denizens of WASP athletic clubs. Chest-thumping and chest-bumping all the way, they used ‘secular Jewish masculinity’ to get published in the right magazines and to impress America and one another.

There is an element of truth in this – the description fits Mailer to some extent. As Grinberg shows, Podhoretz, bursting with ambition and then chagrin, has behaved like an angry teenager all his life. But the others? Grinberg characterises ‘secular Jewish masculinity’ not as a style of behaviour but as a constructed ideology that governed the New York group’s conduct. Their radicalism in the 1930s was a way of attaining virility. After the war, when many in the group adopted the attitudes of Cold War liberalism, the transformation was produced not by the realities of Soviet power or changes in American life but by the desire of Jewish intellectuals to seem tough. Grinberg similarly sees the neoconservatism that some of the New York intellectuals pursued all the way to the dining room of the Reagan White House as the desire to express masculine strength.

McCarthy apparently ‘performed secular Jewish masculinity in her writing’ – quite a stunt for a boastfully promiscuous young Catholic. Grinberg appears to think that satire – McCarthy’s favoured mode – is a male form of composition. Hardwick, whose writing about literature was emotionally candid, also ‘performed secular masculinity’. Here is Hardwick on Emily Brontë:

Wuthering Heights is a virgin’s story. The peculiarity of it lies in the harshness of the characters. Cathy is as hard, careless and destructive as Heathcliff. She too has a sadistic nature. The love the two feel for each other is a longing for an impossible completion … Emily Brontë appears in every way indifferent to the need for love and companionship that tortured the lives of her sisters. We do not, in her biography, even look for a lover as we do with Emily Dickinson because it is impossible to join her with a man.

This is hardly Rahv’s manner of writing about a woman. Yet Grinberg, relentless in her insistence on ‘male’ characteristics, notes that Hardwick was ‘sharp’.

Arendt, meanwhile, was accepted in the 1940s because she ‘already wrote like a man’. Reading The Origins of Totalitarianism as a student, I was startled by a sentence in the preface in which she mocked the helplessness so many felt in the face of Nazism and Stalinism. ‘To yield to the mere process of disintegration has become an irresistible temptation, not only because it has assumed the spurious grandeur of “historical necessity”, but also because everything outside it has begun to appear lifeless, bloodless, meaningless and unreal.’ Is that sentence male or female? Does it matter?

Grinberg is quite right to say that the men were combative, especially Rahv, the art critics Greenberg and Rosenberg, and Howe (in his political pieces). The New York group lived on the edge of their nerves. But Grinberg slights the consequential content of their disputes and ignores what could be seen as the group’s ancestors, the Russian political intelligentsia before and after the revolution, whose habits of derision were a way of facing down opponents. The Russians, including Trotsky, could act and speak in lethal ways. But in America why shouldn’t a pugnacious style in intellectual argument be seen as cleansing, revivifying, generative?

Grinberg’s handling of Lionel Trilling is representative. In a New Yorker essay in 2008, Louis Menand made an accounting of Trilling’s discomfort with himself. He hated the placid professional role of liberal humanist that he had so carefully put together in his decades at Columbia. ‘He was depressive, he had writer’s block, and he drank too much. He did not even like his first name. He wished that he had been called John or Jack.’ Most of all, he wanted to be a novelist who enjoyed the rampaging id in the way that he imagined Hemingway enjoyed it. But Hemingway was depressive, alcoholic, suicidal, often mean in petty ways, compulsive more than free. Trilling’s Hemingway was his own self-negating fantasy.

As Grinberg admits, Trilling was mild, with a gracious manner shadowed by the task of retaining a civil exterior when he was raging inside. He certainly looked burdened, his eyes heavily pouched, his shoulders sagging, a cigarette (two cigarettes in David Levine’s caricatures) always in his hand, a man wearied by liberalism’s failures, American literature’s failures. Grinberg recounts a fine moment early in his career. In 1936, Trilling was informed by the English Department that as a Marxist, a Freudian and a Jew, he would be ‘uncomfortable’ staying on at Columbia. But he stood up to his colleagues, telling them he was better than anyone else they could get, and they relented. It was an uncharacteristic act of aggression, which freed him to finish his stalled dissertation on Matthew Arnold. ‘Lionel was writing like a man,’ Grinberg concludes. But this attempt at male self-possession didn’t last. In 1947, Trilling published The Middle of the Journey, an interesting but excessively mild novel about an ex-communist (based on Trilling’s garrulous undergraduate friend Whittaker Chambers) and the milieu of the Popular Front years. It got mixed reviews and sold poorly, a failure Grinberg describes as ‘emasculating’. She notes that he never completed another novel.

After Trilling’s death, Diana vented her grievances in interviews, claiming that he had thrown away the early drafts which revealed how much her editing had improved his published work. In 1993, she issued a biography of their marriage, The Beginning of the Journey, which, despite many passages of fondness for her husband and much arresting intellectual and social history, is marred by her many gripes and feuds, her chagrin over her delayed recognition as a writer – and her husband’s ineptitude around the house, on the tennis court, in financial matters. One reviewer concluded: ‘The complaint is basically the same from start to finish: Lionel wasn’t much of a man,’ a judgment Grinberg quotes. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

Trilling’s ambivalence and occasional bursts of passionate emotion made him the most fascinating of the group’s literary critics. In the preface to his first collection, The Liberal Imagination (1950), he states that ‘in the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition,’ though he complains, in many essays in the book, and in later books too, that in its great task of reducing suffering and enhancing justice, liberalism was lacking in every way, functional and unimaginative as a system of administration, crudely self-congratulatory in its literary forms.

His collection Beyond Culture (1965) was a response to the decade’s dream of escaping social bonds into a realm of pure freedom. In an earlier essay, from 1954, on Mansfield Park, he claimed that Jane Austen knew that ‘spirit is not free, that it is conditioned, that it is limited by circumstance’. Yet her fictions demonstrate that ‘only by reason of this anomaly does spirit have virtue and meaning.’ By finely gauging ‘virtue and meaning’, Austen initiated the modern habits of close personal observation and judgment:

She is the first novelist to represent society, the general culture, as playing a part in the normal life, generating the concepts of ‘sincerity’ and ‘vulgarity’ which no earlier time would have understood the meaning of, and which for us are so subtle that they defy definition, and so powerful that none can escape their sovereignty. She is the first to be aware of the Terror which rules our moral situation, the ubiquitous anonymous judgment to which we respond, the necessity we feel to demonstrate the purity of our secular spirituality, whose dark and dubious places are more numerous and obscure than those of religious spirituality.

Terror seems an extreme way of describing a regimen of self-observation. Menand reports that Trilling had violent dreams, which frightened him badly. He was locating his own wretched restraints in the moral realism of Austen’s fiction. In life, he remained a tightly buttoned, Freudian man paying for civilisation with outsized discontent.

His hesitations and doubts in the 1950s and after were annoying to many in the group; they took such quirks as a sign of increasing conservatism, a withdrawal from radical criticism of American society. The Trillings were never party members, but many of their friends had been and they had participated in cultural events organised by party members. After the war, Trilling could not have been mistaken for a radical. But the annoyance directed at him was a hidden acknowledgment: the New York group, with the notable exception of the democratic socialist Howe, was moving to the right. They were still liberals (most of them), but they had shed any pretence of radicalism. During the war, they had been intellectually inert. At first, they were mostly isolationist, worried that US participation would lead to fascism at home. They repeated the old Leninist analysis of the new war as a battle between competing imperial powers. They underestimated Hitler and Stalin (Arendt straightened them out on this). Except for Kazin, who was sure of it early in 1942, they didn’t register the extent of the Jewish slaughter. Kazin remained bitter about this for the rest of his life.

The wartime numbness was succeeded by a half-embarrassed, half-relieved acceptance of their unequal, philistine, dishevelled but vibrant country. America had lost 400,000 men in the war, but had not been invaded; the rudiments of democracy had held, the rudiments of a welfare state had been established, racism was now openly discussed as a national scandal. And, as the US became the bulwark against Soviet expansion in Europe, the Marshall Plan was a masterstroke. Most seriously, American capitalism, as the New York group reluctantly acknowledged, was more flexible and adaptable than anyone had imagined, absorbing and selling back any form of rebellion as an exciting new lifestyle. Modernism, they thought, was dissolving into parody and spectacle.

Trilling’s abandonment of radical critique was necessary to his own equilibrium, but some of the others insisted they were merely confronting reality. Alienation, the fallback state of American artists and intellectuals for decades, began to seem smug or irrelevant (Bellow mocked it), an ersatz version of the French intellectuals’ war against the bourgeoisie. The abandonment of critique was accompanied by increasing individual security: jobs and sometimes tenure in the universities (Bell at Columbia, then Harvard; the sociologist Nathan Glazer at Berkeley, then Harvard; Rahv at Brandeis; Howe at CUNY). They had decent book contracts, well-paying articles in the New Yorker or Esquire, vacations in Europe rather than in the Berkshires. Zionism didn’t take hold among them: America was Zion enough.

Idon’t mean to imply that there was an intellectual falling off after the war. On the contrary, there was marvellous writing not only in PR but in the new magazines in which the New York group became involved: Macdonald’s pacifist and satirical politics (between 1944 and 1949); the initially eloquent, then increasingly reductive and hawkish Commentary (founded in 1945); Howe’s earnest social-democratic Dissent (1954); the New York Review of Books (1963), which, after its early years drawing on the energies of the New York group, became almost as much Anglo as American; and the Public Interest (1965), Kristol and Bell’s neoconservative policy quarterly in which the alleged failures of Lyndon B. Johnson’s ‘Great Society’ legislation were picked apart.

What political passion remained was anti-communist, but the New York writers found themselves in an odd quandary, as their long-held obsession was exaggerated and vulgarised in the McCarthy era. They had suddenly to fight a two-front war, against the remnants of cultural Stalinism on one front and McCarthyism on the other. Many were so contemptuous of the old party members and fellow-travellers, and so impressed by their own virtue, that they remained silent as the civil liberties of McCarthy’s victims were systematically violated.

In the 1960s, freshly born right-wingers like Kristol and Podhoretz campaigned against what they took to be any signs of ‘weakness’ in the prosecution of the Vietnam War. Most of the New York intellectuals remained liberals, but what did that mean? Bell, who drifted into neoconservatism, then out again, refused to be crowded into a single category. He defined himself as a socialist in economics (redistribution, universal satisfaction of basic needs), a liberal in politics (individual rights and rewards according to merit) and a conservative in culture (the Western canon, the centrality of judgment in the arts). Whether or not the others subscribed to Bell’s tripartite identity, many of them embodied it.

PR nearly split apart over Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem, published in 1963, which suggested that the European ghetto leaders who furnished the Nazis with the names of Jews in their communities had made the task of extermination considerably easier. Intellectual honesty, Mary McCarthy said in an impassioned defence of Arendt, had fallen victim to ethnic partisanship. A few years later, Howe hinted that the fury of the Jewish response may have been caused by residual guilt over how little American Jews had done, or even known, during the Holocaust. It was a brutal moment.

The Arendt dispute was illuminating, but it also suggested an infusion of guilt into PR’s consideration of large social issues. During the next decade, the magazine wrestled with Black Power and was baffled by the student protesters at Columbia and elsewhere who turned their anti-war, anti-racist outrage against the universities. The new styles of radicalism left most of the group cold. Howe in particular hated the New Left’s tolerance of Mao, its celebration of Che. In turn, he suffered the rejection of young men like Tom Hayden, who said, in effect: we are out there getting our heads cracked while you are sitting in armchairs talking to us of Stalinism.

In the 1964 issue where McCarthy defended Arendt there was a disturbing new voice: Susan Sontag. Later that year she dropped her bombshell, ‘Notes on “Camp”’, which offended every piety the New York intellectuals held dear. ‘The distinction between “high” and “low” culture seems less and less meaningful,’ she wrote. ‘For such a distinction – inseparable from the Matthew Arnold apparatus – simply does not make sense for a creative community of artists and scientists engaged in programming sensations, uninterested in art as a species of moral journalism.’ The PR elders, she implied, were out of touch: modernism was very much alive in the cinema, the Nouveau Roman and New York’s radical theatre.

‘We can’t be the avant-garde,’ Phillips noted wanly, but he did try his best to keep up. Bell and Howe worried that not only the hierarchies of culture and criticism but the entire structure of moral distinction had been dissolved in tides of sensory excitement. Rahv, disgruntled, muttered to friends about ‘swingers’, split with Phillips in 1969, moved to Boston and started his own magazine, Modern Occasions. Bitterness gathered in the chill of separation. In 1971, Rahv published a piece by Saul Bellow in Modern Occasions, in the course of which Bellow, speaking of Phillips, said: ‘One of the nice things about Hamlet is that Polonius gets stabbed.’ Modern Occasions lasted only six issues. Rahv, out of place on Back Bay’s elegant Beacon Street and in poor health, died in 1973. Partisan Review continued to appear, with increasing irrelevance, until April 2003, the last issue appearing a few months after Phillips’s death.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.