Biographies of artists often tie the art too directly to the life, as though dramatic experiences were iconographic keys that unlock the work once and for all. Early accounts of artists were modelled on the legends of heroes and saints, and even today they tend towards the epic in scope and hagiographic in tone. Magritte mostly avoids these traps; it is deeply researched, stylishly written and unusually insightful about its subject. For Alex Danchev, whose academic field was international relations but whose many books include lives of Cézanne and Braque, this was a last labour of love; he died suddenly in 2016 before completing the final chapter.

There is no getting around certain events. Without warning one night in 1912, when Magritte was thirteen, his mother jumped into the River Sambre near the family home in Châtelet, south of Brussels; she was discovered seventeen days later, naked but for a nightdress covering her head. Like most origin stories, this one is too telling to be entirely true; it has a frisson, as the critic David Sylvester put it, ‘at once Oedipal and necrophilic’. Although Magritte wasn’t present at the scene, he alludes to it in a few paintings. In The Musings of the Solitary Walker (1926), a man in a bowler hat, a recurrent avatar of the artist, stands by a twilit river, his back turned to a female corpse floating horizontally across the canvas. ‘I don’t believe in psychology,’ Magritte remarked much later, no doubt to forestall facile interpretations. ‘There is only one mystery: the world. Psychology is concerned with false mysteries. No one can say whether the death of my mother had an influence or not.’ And of his favourite motifs he insisted: ‘They are objects (grelots, skies, trees etc) and not “symbols”.’

Magritte made exceptions to this rule, though. A hot-air balloon that once crashed near his home and a locked chest that sat mutely near his cot both figure in his work: ‘That chest was the first object that instilled in me the sense of mystery.’ Note the repeated emphasis on mystery rather than meaning, on what is present but unexplained; this play with a revealing-that-conceals is everywhere in Magritte. Of the apple that blocks the face of the bowler-hatted man in The Great War (1964), he commented: ‘Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see … The interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is apparent.’

Another source of fascination was the cinema, which Magritte discovered at the same important age of thirteen. Like other Surrealists-to-be, he was a particular fan of the Louis Feuillade films about the criminal Fantômas, a master of disguise who always hoodwinks the police. In these tales ‘surreal events unfold in banal settings,’ Danchev writes. ‘Fantômas is everywhere, but nowhere to be seen.’ This is true of other characters in the genre that intrigued the young Magritte (Mabuse, Zigomar, Nick Carter), and such inexplicable appearances and disappearances became the main device of his art. Above all it was the technical sleight of hand of early cinema that charmed him, its combination of photographic realism and fantastic effect, or what Walter Benjamin called the ‘blue flower’ of sensuous immediacy produced through intensive mediation. As a child, Magritte contrived plays and pranks with a gang that included his two younger brothers and assorted neighbourhood pals, and he made home movies for much of his life. Theatricality pervades his art: Magritte devised scenarios for his paintings, asking associates to do the same, and conceived pictorial space as a visionary stage where objects appear like props, illusionistically firm yet ontologically weak. His weird elisions transfer the abrupt montage of early cinema into the static medium of painting, but he built up his repertoire of devices from other childhood sources as well – colouring books, postcards, illustrated magazines – and later took many of his motifs ready-made from the Larousse encyclopedia. That this ‘second nature’ of found images could furnish his painting was a lesson learned in part from Max Ernst, whose often cited comment on Magritte – that his ‘pictures are collages entirely painted by hand’ – the younger Surrealist came to resent, probably because it was spot on.

Magritte studied painting, intermittently, with local artists and then, during the First World War and after, at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Like other artists of his generation, he passed through versions of Futurism and Cubism; his distinctive style was sparked only in late 1923 when he saw a black and white reproduction of a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, a recent discovery of André Breton and the Surrealists. From outside the main line of medium-specific modernism, de Chirico demonstrated, for Magritte, ‘the primacy of poetry over painting’: ‘My eyes saw thought for the first time.’ Magritte’s aesthetic language of enigma and surprise was also derived from de Chirico, in whom he found ‘a new vision through which the spectator recognises his own isolation and hears the silence of the world’. De Chirico put into pictorial form the direct juxtaposition of disparate images espoused by the mid-19th-century writer Lautréamont and turned it into the central operation of Surrealist image-making – the now clichéd ‘chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on an operating table’. According to Magritte, de Chirico ‘made space “live” by peopling it with extraordinary objects which gave “perspective” a new face’. In the early 1920s, Ernst adapted this de Chirican space by way of Dadaist collage in order to produce the basic template of the Surrealist picture. In the mid-1920s, Magritte added a cinematic illusionism to this mise-en-scène.

By autumn 1926, Magritte had attracted a Belgian circle of Surrealist aspirants, including the writers Paul Nougé, André Souris, Louis Scutenaire and E.L.T. Mesens. They all suggested themes as well as titles to Magritte, as did later associates such as Marcel Mariën, but Danchev considers Nougé ‘his most important interlocutor and expositor’. Supported by his Belgian allies, Magritte decided to try his luck with the French Surrealists, so in September 1927 he moved with his wife, Georgette, to Paris, where they lived in Le Perreux-sur-Marne, at a protective distance from the volatile Breton. Magritte began his ‘word paintings’ immediately, and more than forty followed during his three-year stay. The first, The Interpretation of Dreams, is characteristic of the group; it presents four images on dark grounds in a two-by-two array of panels separated by painted frames that hesitate between mullions and bars. With one exception each image bears a cursive caption that contradicts it: ‘le ciel’ appears under a leather bag, ‘l’oiseau’ under an open corkscrew, ‘la table’ under a green leaf. Only a sponge is properly named (but then the sponge resembles other things too). Despite the psychoanalytic title – La Clef des songes in the (slightly different) original French – this word painting points less to Freud than to Saussure; it isn’t a dream-rebus so much as a picture-essay on the conventionality of the word-object relationship – on the vaunted arbitrariness of the signifier. Nougé provides an evocative gloss on these paintings: ‘The word can never do justice to the object; it is foreign to it, as if indifferent. But the unknown name may also hurl us into a world of ideas and images … where we encounter things wondrous and strange and come back full of them.’

In November 1927, Magritte went a step further with his ‘metamorphosis’ paintings, which show ‘an object merging into an object other than itself’. An early example, Discovery, presents a voluptuous nude whose flesh has begun to harden into wood grain, but this modern Daphne doesn’t look especially alarmed at turning into a tree. Unlike Marxists such as György Lukács, the marxisant Surrealists searched for ‘the marvellous’ in the effects of reification, though the most famous painting in this group, The Red Model (1935), is horrific enough: it depicts two bare feet becoming leather boots (or is it vice versa?). In the early 1930s Magritte invented other pictorial types, such as the ‘cut-up’ canvases, the best-known of which divides the nude Georgette into five panels that together make a life-size figure. As when a magician saws his assistant in half, these works are too close to tricks – a frequent drawback in an artist who found it hard to resist a gag.

The ‘problem’ paintings are more serious: Magritte believed that some objects evoke others in non-obvious ways; rather than place the usual bird in a cage, why not a massive egg? The result is Elective Affinities (1933), a title that can stand for the series as a whole, for these pictures surprise us by way of an unexpected sympathy between things rather than an obvious disparity. By this time Magritte had begun to read Henri Bergson, whom Danchev quotes here: ‘Our memory runs from the perception to previous images which resemble it and which our impulses have already sketched. Thus it creates afresh a current perception.’ Typically, Magritte came up with a formula for the problem paintings, each of which has ‘three given points of reference: the object, the thing associated with it in the shadow of my consciousness, and the light in which this thing should appear’.

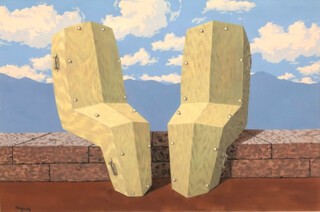

These pictures engaged Magritte for the rest of his life, but he tried out other types in subsequent decades, too, such as the ‘perspective’ paintings, which redo famous canvases by David, Manet and others, substituting wooden coffins for human figures. Perspective was invented, Willem de Kooning once said, so that painters could depict dead bodies; Magritte suggests something similar here, entombing a few exalted French predecessors along the way. This series replays the ‘metamorphosis’ pictures in a mortifying key; a final group called the ‘petrification’ paintings does much the same with the traditional genres of portrait, landscape and still life, which Magritte paints in a stony grisaille. Once again he follows de Chirico, whose later work also showed signs of petrification, not to mention repetition (both de Chirico and Magritte made multiple versions of their most acclaimed pictures). Magritte dabbled in forgery, too, not only of Old Masters (Titian, Hobbema) but also near contemporaries (Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Gris, Ernst, Arp, Klee); on occasion he tried his hand at new banknotes. He was often strapped for cash, so necessity was the spur to trickery.

In the December 1929 issue of La Révolution surréaliste, the house organ of Breton’s group, Magritte published a text entitled ‘Words and Images’, which Danchev describes, with a touch of hyperbole, as ‘one of the seminal documents of 20th-century artistic creation’. Accompanied by little drawings, it essays eighteen possible relationships between word, image and object, among them:

There is little connection between an object and what represents it.

No object is so tied to its name that we cannot find another that suits it better.

Some objects do without a name.

Images and words are seen differently in a picture.

An object encounters its image, an object encounters its name. The object’s image and name happen to meet.

These hypotheses bear primarily on the word paintings, but in 1934, in an essay published in Documents, the journal of the ‘dissident Surrealists’ around Georges Bataille, Magritte made a statement that also applies to many other works: ‘With few exceptions, it is a question of mises-en-scène, which give the illusion of contact with the real, but merely encounter the void.’ This thought leads to his fullest account of his art, in a lecture from 1938 titled ‘Life Line’, where Magritte comes close to relating the devices of his picture-making to the operations of the unconscious – the ways in which dreams and symptoms condense and combine different images and ideas. With specific paintings in mind, he writes of

creating new objects; transforming ordinary objects; changing the substance of some objects: a sky made of wood, for example; using words with images; calling an image by the wrong name … I found the cracks we see in our houses and on our faces more eloquent in the sky; turned wooden table legs lost their innocence if they suddenly appeared to dominate a forest; a woman’s body floating above a city was a fair exchange for the angels which have never appeared to me.

(So much for his mother’s suicide not haunting his work.) In these two texts Magritte envisions painting sometimes as an impediment (like a wall) with everything to discover behind it, and sometimes as an aperture (like a window or a door) that opens onto nothing at all.

Magritte produced some 280 paintings during his time in Paris, almost a quarter of his total output, but his principal gallery failed after the 1929 crash, and most of his work went unsold at the time. Close to broke, he and Georgette quit Paris for Belgium in July 1930. Although Breton owned seven of his paintings, and Magritte gave other works to Louis Aragon and Paul Éluard, his relationship with the key Surrealists was an uneasy one. Danchev interprets this as a matter of French condescension to the Belgian and the Belgian chafing under the French, but he notes real differences in aesthetic views as well. Breton called Magritte the ‘cuckoo’s egg’ of Surrealism, and though his work did eventually hatch in the Surrealist nest, he had little interest, as a very calculated painter, in Surrealist practices of automatist drawing and symbolic object-making; he preferred his picture puzzles reasoned out. The break with Breton came at a party at his house: Georgette wore a cross and Breton insisted she remove it; she refused, Magritte sided with his wife, and they left. As Breton added another notch to his belt, maybe Magritte took solace in the fact that the excommunicator-in-chief had earlier repudiated de Chirico.

The falling out didn’t last long. In fact Magritte is no less an exemplar of Surrealist painting than Ernst; at their best each elicits the conflict ‘between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is apparent’. Using different techniques, the two artists evoke memories or fantasies in a way that is seductive or traumatic or both at once; for Magritte ‘charm and menace combined can reinforce each other.’ Ernst sometimes riffs directly on the ‘primal scenes’ in which, according to Freud, we tease out fundamental questions of personal origin and sexual identity, while Magritte often touches on more philosophical mysteries: ‘Our gaze always wants to travel further, to see at last the object of our existence, the reason for our existence.’ Magritte is ‘the master of the prying eye, the keyhole, the door, the threshold and the terra incognita beyond’, Danchev writes, and then unexpectedly quotes Kafka: ‘The world will offer itself to you for unmasking; it can’t help it; it will writhe before you in ecstasy.’

Back in Belgium, Magritte made ends meet with work in design and publicity. In the 1920s he had produced wallpaper as well as posters for the likes of Couture Norine. Now, in a garden shed that became known as ‘Studio Dongo’, assisted by Georgette, his brother Paul and Nougé, he did spreads for magazine and fashion catalogues and covers for books and sheet music as well as adverts for ‘everything from fast cars to fur coats, toffees to cigarettes, Pot-au-feu Derbaix to Persan Bitter de marque’. ‘The designs,’ Danchev writes, ‘migrated into his art.’ This is true, but so is the reverse: it isn’t a case of fine art appropriating commercial culture so much as a relay between the two. In both registers Magritte knew how to play on what Benjamin called, around this time, ‘the sex appeal of the inorganic’. In his documentary The Century of the Self (2002), Adam Curtis argues that advertising co-opted psychoanalysis, and the same could be said of Surrealism – that advertising exploited its art of subliminal suggestion for the purposes of commercial persuasion. For Danchev this is no bad thing. He begins his book by remarking that Magritte ‘is the single most significant purveyor of images to the modern world’. He even sees Magritte as the distant source of the logos of both CBS and Apple, which makes him ‘the dream merchant of our time’ as well. But this argument may be better suited to other Surrealists, such as Man Ray and Salvador Dalí, who were happy to use their art to promote any and every campaign. Magritte began with colouring books, postcards and illustrated magazines, so for him the lines between low and high culture were blurred from the start. What’s more, his art often elicits a feeling of unease that advertising can’t really abide.

Magritte had an influence on other artists, but the effect was mostly delayed. For more than twenty years, Danchev tells us, his famous painting The Treachery of Images (1929) ‘languished unknown and unregarded’. Magritte had his first retrospective in Brussels in 1954; that same year a show titled ‘Word v. Image’ at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York exposed his work to young American artists like Jasper Johns, who purchased a Magritte (a third version of The Interpretation of Dreams) as soon as he could afford it. Further retrospectives followed in Dallas and Minneapolis and then, as Pop exploded, at the Museum of Modern Art in 1965. The Pop-adjacent artists Ed Ruscha and Vija Celmins learned from Magritte how to render mundane objects mysterious, but his greatest legatee was his countryman, Marcel Broodthaers, who turned a Magrittean appropriation of images and objects into an allegorical questioning of the operations of art world and culture industry alike. More recently, the American artist Robert Gober has taken up Magritte’s way with simulacra – that is, objects that look eerily real but aren’t – in order to explore fantasies that are both private and public.

I like the idea of Magritte as much as his art. David Sylvester, who oversaw the catalogue raisonné of the work, felt similarly, and I imagine Michel Foucault did too. In 1968, in the midst of the Magritte revival, Foucault published an extraordinary meditation on his work, focusing on The Treachery of Images, which depicts a large pipe with the cursive caption ‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’ (there is an English version as well). Foucault calls it a calligram – a picture of words arranged in the shape of the object they describe – which Magritte has ‘carefully unravelled’ in a way that makes it impossible to say that ‘the assertion [‘this is not a pipe’] is true, false, contradictory, necessary’. In the process Magritte disturbs the two principles that have dominated Western painting since the Renaissance: not only the ‘rigorous separation between linguistic signs and plastic elements’, but, more important, the ‘equivalence of similitude and affirmation’. By this Foucault simply means that the likeness of a representational image ‘affirms’ the reality of the object it depicts. Abstract painters such as Kandinsky and Malevich did away with similitude, but they affirmed reality nonetheless; it’s just that they relocated it beyond the phenomenal world in a noumenal one, understood to be spiritual, Platonic or otherwise transcendental. (In Hegelian terms, abstraction ‘sublates’ representation – at once cancels and preserves it.) Magritte did the opposite: he maintained similitude but broke its ‘representative link’ to any reality. In his paintings there is no referent, nothing beneath or beyond the image; the real is undercut from within the realm of likeness, which arguably makes such simulation more radical than any abstraction. ‘Henceforth, similitude is restored to itself,’ Foucault writes. ‘It inaugurates a play of analogies which run, proliferate, propagate … without affirming or representing anything.’ Magritte phrases it this way: ‘Visible things always hide other visible things, but a visible image hides nothing.’ Or again: ‘It is a question of mises-en-scène, which give the illusion of contact with the real, but merely encounter the void.’ In this respect his art might be the ‘cuckoo’s egg’ not only of Surrealism but of painting at large. Gerhard Richter once suggested this very epithet for his own pictures, and it is no accident that Foucault developed his simulacral reading of Magritte soon after Pop first appeared (Pop influenced Richter profoundly). Certainly Foucault saw Warhol’s silkscreens as simulacra, as did Gilles Deleuze, Roland Barthes and Jean Baudrillard, and some of us approached a good deal of postmodernist art in this way too.

How does the play with simulacra relate to the left politics that Magritte supported? ‘In life as in my painting, I am also traditionalist, even reactionary,’ he once said. ‘In politics, on the other hand, I am resolutely revolutionary.’ This overstates the case on both fronts. Although Magritte joined the Communist Party, he did so late, in September 1945, and it was an unhappy experience: ‘Conformism was as blatant in this milieu as in the most narrow-minded sections of the bourgeoisie.’ Nougé is our best guide here. A man of contradictory parts – biochemist, talented writer, incisive theorist, relentless alcoholic – Nougé was also, in 1919, a founding member of the Communist Party in Belgium. ‘Our dealings with our fellow men, and with ourselves, are deeply tainted by the social conditions now imposed on us,’ he wrote. ‘This perversion extends to our relationship with familiar objects, those objects that we believe to be our faithful servants, and that slyly, dangerously, rule us.’ On this score, he added, The Red Model, the nasty painting of the feet-turned-boots, ‘shrieks a warning’. Clearly, Nougé wasn’t seduced by the sex appeal of the inorganic; he saw more alienation than marvel in the world of capitalist production and consumption, and he thought that Magritte captured this sense of estrangement effectively. Magritte came to agree: the typical object in his pictures ‘has lost precisely that “social character”; it has become an object of useless luxury, which may leave the spectator “feeling helpless” … or even make him ill.’ This is close to nausea à la Sartre, but Magritte was referring less to a general existential condition than to a particular socio-economic order, which for him was no order at all.

Nougé was also alert to the simulacral nature of this art. ‘It has to be admitted,’ he wrote in a letter to Magritte from November 1927, that the ‘inexplicable object’ in these pictures ‘conceals nothing’. ‘You have constructed an infernal machine. You are a good engineer, a conscientious engineer. You have left nothing undone in order to blow up the wall … Whatever is behind it, you will discover with us.’ What both men hoped to find, anticipated by ‘the sight of the new order’ in the paintings, was ‘a change in the order of things’ altogether. With a note of desperate optimism, Nougé asked: ‘Who suspects that this thin canvas rectangle contains something that can change for ever the meaning of justice and love, the meaning, the style and the tension of existence? … The doors swing. GO THROUGH OR DIE.’ The last word goes to Magritte. ‘We are the subjects of this incoherent and absurd world,’ he said in a lecture given in Antwerp in November 1938. ‘It still holds up, this world, for better or worse; but aren’t the signs of its future ruin already visible in the night sky?’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.