Goodbye, Circumflex

Jeremy Harding

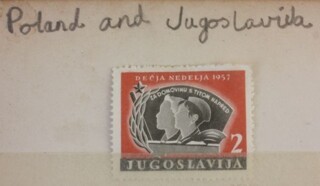

The diacritical mark, that puzzling addition to a recognisable letter, arrived in my life at about the age of six, like an insect lighting on the page of a school textbook. Only it happened out of school, in the world of foreign stamps, where I first encountered ‘accents’. My arbitrary collection included a stamp from Hungary commemorating the ‘technical and transport museum’ – Közlekedési Múzeum – and another from Yugoslavia commemorating what I think is a children’s day: ‘Decja Nedelja’ (1957), with a wingless creature fixed to the lid of the ‘c’. French stamps were easy to obtain: on these you could see your first cedilla, even if you didn’t know it. All these marks were mysterious, but mystery gets irritating before long, and mostly I wanted to swat them away.

The French have done just that: for school children of the future the circumflex accent will be a rarity. It’s part of a 25-year-old plan to rationalise spelling, and it means that kids are likelier to encounter this once-familiar mark (hyphenation is also under attack) in Tolkien (Nazgûl, or Nâzgul, who cares post-Pêter Jacksôn?) than they are in their textbooks. If they go on to read Joyce they’ll find it in Finnegans Wake – ‘Yard inquiries pointed out... that they ad bîn “provoked”’ – and if they ever do Greek, they’ll discover it’s been around for a long time: versions of the New Testament had diacritical marks in the fifth century.

The circumflex came into use in France much later, in the 16th century, and the Academie Francaise – let’s dump the acute and the cedilla – haven’t fought to the death to hang on to this trifling novelty. Diacritical marks are now ironic, as they were for Joyce. Anglo-Saxon bands use them as a design feature, even if they privilege the umlaut, a rare mark in French: Mötley Crüe, Maxïmo Park, Motörhead etc. Amon Düül is dying proof that no one should listen to a band with more than one umlaut.

The new edict will make teachers’ lives much easier. It also hints at a return to the age of pre-regulated spelling, enjoyed by most scholars and poets up through the Renaissance. When one set of rules is cast aside, another can join it later in the same obscurity. If we’ve really set our hearts on spelling bees, Göögle will be a far more powerful consensual institution than the Academie Francaise.

I used to toil through Villon – sent there, like most British poetry readers, by Basil Bunting – trying to figure out where the circumflex would have applied in modern French. ‘Ou gist, il n’entre escler ne tourbillon.’ Roughly, in modernised French: ‘Là où il gît, ni éclair ni tourbillon n’entre.’ No lightning or whirlwind can bring ‘le povre Villon’ back from the grave.

‘Gist’ is a nostalgic’s lullaby. The circumflex on gît keeps the cradle rocking, and reminds us that an ‘s’ has gone missing over centuries of usage. Châtelet for chastelet, prêtre for prestre (as in Prester John), plâtre for plaster, abîme for some early French equivalent of abyss. From côte to côte, the circumflex tells us how closely French was related to other languages, often via Latin. But according to the Academie Francaise even educated people (‘les personnes instruites’) have trouble with the circumflex, and there’s no need to build a diacritical cult around a consonant that’s disappeared from any given part of speech. Nos ancêtres les Gaulois would have agreed.

Comments

-

7 February 2016

at

12:16am

Alex Drace-Francis

says:

Közlekedési Múzeum means just Transport Museum - the 'Technical and' (Műszaki és) was added later, in 2008.

-

7 February 2016

at

10:16pm

UncleShoutingSmut

says:

Unfortunately this post is likely to leave readers with a very partial idea of what is going on. Firstly, there is no "edict": all that has happened is that publishers of educational textbooks have decided collectively to apply the "recommandations" of 1990, where previously only one or two (at least one to my knowledge: Hatier) did so.

-

8 February 2016

at

2:04pm

Alan Benfield

says:

Hmm, but where does your hatred of diacritics leave the Western and Southern Slavic languages?

-

9 February 2016

at

8:09am

David Gordon

says:

@

Alan Benfield

The "r" with a haček is not so difficult to pronounce, because many of us learn to say Dvořák's name, and there it is, the sound you need to make.

-

9 February 2016

at

11:03am

Alan Benfield

says:

@

David Gordon

It's not always so easy, David, imho: try pronouncing Pařižská (street off the Old Town Square in Prague). In my experience, even some Czechs tend to elide the ř because it's too hard to say followed by the iž (although they always claim not to). Czechs seem to place pronunciation of the ř as a mark of whether a foreigner really cuts the mustard or not (In my adopted country The Netherlands, Hollanders take correct pronunciation of the guttural 'ch' (as in, e.g. Scheveningen) in the same way. However hard I try, I never seem to get it right (according to my Dutch wife, anyway)).

-

10 February 2016

at

8:49am

David Gordon

says:

@

Alan Benfield

Well I agree Alan, it is indeed fun, and also very interesting. Why is it that a Dane, or German from Lower Saxony, can have a near-perfect English accent, but Bavarians always sound like ... Bavarians?

-

10 February 2016

at

11:01am

Alan Benfield

says:

@

David Gordon

True, being a copycat is essential when trying to speak another's language well, a lesson I learnt from the head of modern languages at my secondary school (who spoke French, German, Russian, Spanish and Italian fluently). He had, in English, a very plummy patrician accent, but when he slipped into another language he changed completely - gestures and facial expressions included - and became, as close as I could discern, a native. He insisted that nobody could become a truly fluent speaker without acting, consciously or not. This, I think, is only partly true: I have colleagues here in The Hague who speak several languages fluently, but betray themselves as Brits as soon as they open their mouths. But, as Dr. Johnson remarked about something else, like a horse walking on its hind legs, it is not done well, but you are surprised to find it done at all.

-

9 February 2016

at

8:14am

David Gordon

says:

Oh dear - can't spell "pronunciation". If it had been in Czech the sound would have told me about my error.....

-

6 March 2016

at

2:38am

Timothy Rogers

says:

In case anyone on the board comes back to this, which is fascinating, a few remarks and reminiscences. It was, I think, the image of a dog walking on its hind legs (more remarkable in horses, but Lippinzaners are trained to do it) that Samuel Johnson found remarkable, but his point of comparison was to a "woman preacher", which truly astonished him.

Read moreAnd Nedelja means 'week' here, not 'day' (although it also means Sunday).

Second problem: the circumflex isn't about to become a "rarity", or less common than in Tolkien, since a great many were entirely unaffected by the proposals of 1990. The only circumflexes to be made optional were in fact those on i and u, whose removal can have no impact on pronunciation. Whether you write "connaît" or "connait", "goût" or "gout", the word will sound exactly the same. This is not true of circumflexed a, e, and o, which carry a phonetic value, indisputably for ê and ô, more marginally for â (the back pronunciation of â is now a regionalism). So, to take Harding's examples, gît and abîme do have alternatives without the diacritic, while prêtre, plâtre, and côte do not. Châtelet would not have been affected anyway, since it is a proper noun.

Concerning English, one place where diacritical marks are not "ironic" is the New Yorker magazine: it has always held to an idiosyncratic use of the "umlaut" (some would say dieresis, but what the hell) to mark repeated, as opposed to lengthened, vowels: "Mirren's goal is not to reënact but to interpret", "rival conceptions of how the two countries should exert and coördinate their respective national powers" are examples from recent issues.

Czech, Slovak and all the dialects written in Latin script that used to be grouped under 'Serbo-Croat' all use what the Czechs and Slovaks call the haček (which you will see on the c of the word 'haček'). This makes a c into a ch, an s into a sh, a z into a zh and an r into a rzh (hard to pronounce, that). In Czech and Slovak these are treated as letters in their own right and have their own chapters in the dictionary for words which begin with them.

True, the Poles have avoided this by using the compound consonants cz, rz, sz and zh, but Polish is also hardly lacking in other modifiers.

Obviously St. Cyril got it right: have a letter for every noise you need to transcribe - which is why Russian has 33 letters. Oops! Wait a minute, there are actually two with diacritic marks: Ё and Й.

Rats! Pesky foreign orthography!

There is a great deal to be said for a language like Czech, where each letter is pronounced according to pretty exact rules. If a Czech person is asked about the spelling of a Czech word, he or she will normally just say the word again, with exact pronounciation. The spelling is then all there to be heard.

This is much easier than a language like Danish, where othography has little relationship to pronounciation. One exercise that is often used in early Danish language lessons is to be given a printed passage in Danish, and the pupil has to go through crossing out every letter that does not sound. Often, more letters are crossed out then letters remaining.

But true, Czech is utterly phonetic: I remember a friend once saying that I should try using gel in my hair: she pronounced the word with a hard g. When I pointed out that the word was a French one and should be pronounced with a soft g, she demurred, saying that in Czech g was always hard: if it needed a soft sound, it would have to be spelt 'děl' (as in anděl (angel)). Such are the iron rules of Czech orthography.

And talking of languages 'where orthography has little relationship to pronunciation', what about ours? I am sure Danish (or at least Old Norse') had a hand in our cockeyed spelling, as did Norman French, bits of Celtic languages, vowel and consonant shifts and all the rest.

Which makes it fun for the non-native speaker...

Denis Healey had a phrase about the ability of the parrot being an important help in getting the pronunciation right, but I think my parrot is highly selective. I actually find words even as tongue-tying as "Pařižská" not too bad, and my accent gets me mistaken for a native in Prague until my grammar and vocabulary let me down, after a few seconds. I can even last for minutes in French in France. But my Portuguese friends fall about laughing as I try and pronounce their names, and as for Dutch. after a long lesson from a Dutch friend trying to get me to say "van Gogh" he gave up and I decided to stick to my one phrase, which is "dank u wel" to the KLM cabin crew.

Undoubtedly, doing it well requires making the effort to force yourself to make the right noises, which often requires retraining your mouth, tongue, throat and face to behave in a new and often difficult way. This can often be a tall order: U Řezáčů řinčel řetěz při řezání řezanky (Czech tongue twister - "At the Rezaces you could hear chains while they were cutting grass").

But then, weirdly, Slavs have a problem with something as simple as the 'au' diphthong (or its homophones), hence 'avto' for car and 'kovboi' for cowboy.

A footnote on Dutch: while the Flemish version is pronounced phonetically (at least unless you are listening to dialects, in which case all bets are off), in Holland (I mean the provinces of North and South Holland) people often attempt to anglicise certain words they see as English, particularly those with an 'a' somewhere. A classic example is tram, which Hollanders invariably pronounce 'trem', giving it a certain Afrikaner twang.

Unfortunately, this means my name often gets mispronounced as 'Ellen' - which does not please me a lot. But mastering the numerous ways to pronounce 'a' in English is a tough one.

There's a short saying in Czech that translates as "stick a finger in the (or your) eye". They like to use it to mess with the minds of foreigners who complain about what they think are difficult consonant combinations and a paucity of vowels - it has no vowels in it. A Czech friend of mine wrote this out and explained it to me, but, when I pointed out to him that in fact many of the words included short-vowel sounds (either "ih" or "eh" or "uh" between sets of consonants) he wouldn't accept that. I had a similar discussion with a hotel desk clerk in Zagreb, a friendly guy who taught me some short useful phrases. I asked him about where the "short vowel" sound should be made in the common word "trg" (meaning square or plaza). He said, "no vowel", but he pronounced it "trig" rather than "tirg" - the vowel is certainly fleeting, but it's there.

I try to get the accent right in these short phrases, and, when making up simple combinations of them, I don't worry about grammar, of which I know nothing in the Slavic languages. This can lead to funny results. My wife and I were walking along a side-street in a run-down residential neighborhood in Bratislava (always Pozsony to the Hungarians and formerly Pressburg to the German Austrians) and we passed a middle-aged woman sitting on her front steps, smoking a cigarette and accompanied by a large, dirty dog. I said, "dobry den" (good-day, hello), and she laughed and said, "dobry den, turisti". Feigning indignation, I threw everything I knew into the sink, as it were, and said, "je nesem turisti, nesem svaty, nesem pes jiste nesem maduros", which is, "I'm no tourist, I'm no saint, I'm not a dog and I'm definitely not a Hungarian." She laughed, and assuming I knew Czech or Slovak well, she chattered away in her native tongue (presumably Slovak). When she paused to look at me for a response, I gave her a silly smile with a shoulder shrug and out-turned palms to indicate that I was as dumb as her dog, which made her laugh more. I gave her a cigarette and we parted friends. My wife, looking at me doubtfully, asked me what had just happened. I told her, and she said, "You're an idiot". Now that would have been a useful phrase to learn.