Negative Typecasting

Louis Mackay

‘Gothic’ or ‘Black Letter’ script was used by monastic scribes in many parts of Europe from the 12th century. Early printer-typefounders, including Gutenberg and Caxton, imitated handwritten Black Letter in the first moveable type. In Italy, Gothic typefaces were soon challenged by Roman or 'Antiqua' letters (which owed their forms to classical Latin inscriptions) and Italics; and in much of Northern Europe, too, Black Letter forms were largely obsolete by the mid-17th century. In Britain, the ‘Old English’ variant survived in the ceremonial ‘Whereases’ of indentures and statutory preambles. It lingers on in ‘Ye Olde Tea Shoppe’ signs, Heavy Metal rock graphics, neo-Nazi tattoos and the mastheads of the dailies Telegraph and Mail.

In Germany, however, the local ‘Fraktur’ and ‘Schwabacher’ variants of Black Letter resisted displacement. As cultural tensions developed in the German-speaking world between classicism and the liberal enlightenment on one side, and romanticism and conservative nationalism on the other, the rival letter-forms became embroiled in the dispute. Nationalists, invoking philological studies of proto-Germanic languages, claimed an essentially Germanic character for Fraktur, and thought it had a role in defending the German language against corruption. ‘German books in Latin letters,’ Bismarck once said, ‘I don’t read!’

Bismarck's remark was amplified by Adolf Reinecke, a proto-Nazi Aryan supremacist of the Wilhelmian epoch, who advocated German colonisation of Eastern Europe and ‘liberation from the Jewish plague’ under the sign of the swastika. His 1910 treatise Die Deutschen Buchstabenschrift (‘The German Alphabet’) was a manifesto for Fraktur’s Germanness. It also claimed that it was more readable, more compact in printing, healthier for the eyes and destined for supremacy through the irresistible rise of the Germanic-Anglo-Saxon world.

German conservative and nationalist circles were largely sympathetic to such views. Hitler was not. He disliked Fraktur. ‘Your supposedly Gothic internalisation ill-suits this age of steel andiron, glass and concrete,’ he declared in 1934. Even so, Fraktur and a simplified derivative, Gebrochene-Grotesk, continued to be used as the standard public letter-form in much of Nazi Germany’spublishing, advertising and signage – some of which survives today – and Jewish publishers were expressly forbidden from using Fraktur because the regime considered its Germanic essence inadmissible to them.

Like Reinecke, Hitler expected that German ‘in a hundred years will be the language of Europe’. Unlike Reinecke, he thought that Fraktur – and its stablemate, the ‘Sütterlin’ handwriting taught inschools – were not aids but hindrances to achieving linguistic dominance. In early 1941, with much of Europe under Nazi control and high expectations of conquest in the East, Hitler banned the useof Fraktur and Sütterlin in favour of Roman type and standard handwriting.

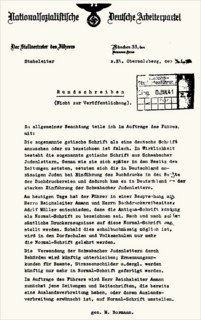

How could immediate compliance with such a volte-face be ensured, and discussion of its implications suppressed? There was a simple answer to that. As Carlos Fraenkel writes, paraphrasing David Nirenberg’s Anti-Judaism: The History of a Way of Thinking, ‘when Westerners find fault with some aspect of society or culture... they always disparage it as a Jewish aberration.’ On 9 January 1941, Martin Bormann issued a confidential circular on behalf of the Führer to party officials:

To regard or describe the so-called Gothic script as a German script is false. In reality the so-called Gothic script consists of Schwabacher Jewish letters. Just as they later took over possession of newspapers, Jews resident in Germany when the printing of books was introduced took over book-printers, and thus the strong influence of Schwabacher Jewish letters came into Germany.

In other words, according to Bormann, since the time of Luther, generations of enthusiasts for the essential Germanness of Fraktur – Bismarck, Reinecke, most Nazis, though not Hitler – had beenduped by a centuries-old Jewish typographic plot.

Bormann evidently missed that the party letterhead on his circular was printed in Fraktur.

Comments

-

27 May 2015

at

10:16pm

Phil Edwards

says:

Why "Fraktur" (and "Gebrochene"), I wonder.

-

27 May 2015

at

11:24pm

Louis Mackay

says:

In German, varieties of of Black Letter that have sharp angles like a snapped branch in the letter form, are known as "gebrochene Schrift" (broken script), by contrast with those that have curves, like a bent twig, which are called "Rundgotisch" (round Gothic) or "Rotunda". The word 'Fraktur" suggesting "fracture" in English, reflects the same meaning. Typical Fraktur and Schwabacher letters in fact combine elements of both the broken and the round, but it is the broken character that classifies them. - LM

-

28 May 2015

at

10:35am

Bolbol

says:

A fascinating story. Could we have it brought up to the present day? Not so long ago I studied German using a US textbook published in 1941 (i.e. clearly meant to help Americans joining the war effort in Europe). After the first 7 chapters, which were in Latin script, the entire thing was in Fraktur, with the result that my classmates and I learned German in a script that hadn't been widely used for decades. When I asked our teacher why Germans had stopped using Fraktur (and related 'broken' or 'Gothic' typefaces), he said that the German publishing industry had been concentrated in Leipzig and most of the presses were destroyed in bombing raids. New presses were purchased after the war from countries using Latin typefaces. I suspect there is more to the story, however - perhaps something to do with a reaction to the Nazis, despite their volte-face described here? And what about Austria?

-

28 May 2015

at

3:26pm

Louis Mackay

says:

Austria would have been subject to the 1941 diktat as part of the same Reich. The Leipzig headquarters of one of the biggest German literary publishers, Insel Verlag, was completely destroyed by an air raid in December 1943. But the destruction of presses would not have affected which typefaces were used once the machines were running again. "Hot metal" typesetting machines were the norm at the time and all they needed were a set of easily replaceable "matrices" or moulds for each typeface.

-

2 June 2015

at

11:39pm

Stephen Games

says:

@

Louis Mackay

But to get back to Louis Mackay's article, the key issue is the consistency of anti-Semitic accusation in the spite of meandering illogicality. First, Fraktur could not be used by Jews because it was too German; then, Fraktur could not be used by Germans because it was too Jewish. This theme - the construction of foul, "pure", self-contradictory ideologies based on Jew hatred - ought to ring alarm bells with us, for our too ready use of it to explain the various narratives of victimisation and sectarian horror in and beyond the Middle East. It ought to, but it won't, because we're too sure that we're right. We'll just see it as a Nazi aberration, divorced from the present day.

-

28 May 2015

at

4:42pm

Timothy Rogers

says:

The arguments about the “ideological baggage” of these two different kinds of German typeface are heavily influenced by various historical anachronisms. Mr. Mackay’s note on typography in the GDR supports the idea that selection of typefaces depended more on the internal aesthetic standards of publishing houses. As a high-school student of German back in 1960-62, my first exposure to the printed language was through a reprint of a very old Fraktur instructional book. Our teacher insisted on this, as he did on us learning to write in traditional script, which we had to use on all tests and exams. The second-year textbooks were in Latin typeface and had been published only recently. Because the teacher was authoritarian and a strict disciplinarian, some of my classmates would refer to him as a Nazi or crypto-Nazi (discussions of recent German history were off-limits in our class, so how could we know what his opinions were?) When we started our lessons his only pronouncement about the typefaces was that we would learn to read and write in “real German”. Maybe he was just a sentimentalist.

-

28 May 2015

at

6:30pm

David Gordon

says:

A fascinating article. My lessons in German, in 1961 - 1962 used a textbook printed in Fraktur, "Heute Abend", designed for use in evening classes: does anyone else remember it?

-

28 May 2015

at

8:04pm

Timothy Rogers

says:

@

David Gordon

I remember this aspect of choosing among three or four languages offered during my high-school days. Some of the older teachers advised those who were likely to go to college/university to take German if they had any intention of pursuing careers in science or technology - "the relevant literature is all in German," was their argument. But I think they were recalling the situation as it was during their time as students twenty or thirty years earlier. The English displacement of German in all kinds of academic journals was already well under way by the 1960s. Except for a few "superstars" in physics (e.g,. Heisenberg) German science had been compromised and intellectually gutted during the 1933-45 years. German technical knowledge and research and development continued at a high level, but the newest theories in physics -- seemingly astonishing and implausible on their face - were being resisted and disparaged as "Jewish" or spurious science. Almost anyone of value was gobbled up by the West or the USSR during 1945-46, so, in addition to the ideology-based retardations of the Nazi years, Germany also underwent a scientific brain drain. By the time any significant recovery had been made, the funding and sponsorship of advanced science in the West was mostly in American and British hands, as were the major journals. Very good "hard science" was being carried out elsewhere (Russia, France and numerous European countries, India, etc.), but the "deomographic reach" of English, as well as its use as a post-war lingua Franca for all kinds of practical purposes, also contributed to this dominance.

-

28 May 2015

at

8:22pm

David Gordon

says:

@

Timothy Rogers

I think you are completely right. Ironically, my teacher was a German Jewish refugee, an excellent teacher and an excellent player of the double bass. I blush to think what he would say to my mistake earlier, in the correct capitalisation of "Pflügers Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie”. I can hear him now, "Nein, nein, nein...."

-

29 May 2015

at

7:46am

Alan Benfield

says:

@

Timothy Rogers

When I was at a grammar school in London from 1966-69, everyone was required to do French, but as a second language the choice was between a living language (German) and a dead one (Latin). I chose German, which, while denying me access to the classics in the original has arguably been much more useful in later life, as my job requires the use of English, French and German. I also recall reading scientific papers at college in both French and German.

-

29 May 2015

at

1:44pm

Timothy Rogers

says:

@

Alan Benfield

At the time that I was in school no one in either (American) public or Catholic schools had exposure to any foreign languages before high-school (which started with grades 8, 9 or 10, depending on how the local school district organized their “middle schools"). I don’t know if this was also true of expensive non-denominational private schools (called “prep schools” over here). I attended a large, all-boys Catholic high school, where students in the “top tier” (also called “the academic track”, with the other two tiers being labeled “business track” and “vocational track”) had mandatory Latin for the first two years of four. As a third- or fourth-year student you could continue with Latin as an elective subject, but you had to take a living language too. We were offered French, German, and Spanish (in the prior decade Italian had been offered due to the presence of a couple of Italian speakers on the faculty). My choice of German depended on an interest in twentieth century history rather than an inclination toward science, but a lot of us were influenced in our choice by the reputations of the teachers. My older brother and several of his friends discouraged me and my friends from taking French by characterizing the French teacher as crazy as a loon, but we soon enough found out that our German teacher was equally dotty. One interesting new element of foreign language instruction had just appeared on the scene – this was the so-called language lab, where, for two or three hours each week we sat in individual booths with a headset connected to a central tape-drive; we listened to German speakers giving the instruction, with a brief test at the end of each session. No English was used on the tapes. The program was the result of the American government’s panic over Sputnik and other well-publicized achievements of “Soviet science”. Washington basically funded the expense of setting up the labs and paying for the instructional materials, and, for Catholic schools like mine, a legal ruling was made that this did not violate separation of church and state regulations because no religious material was being conveyed by the course of instruction. The emphasis on this aspect of instruction was on accent, while it was assumed that vocabulary and grammar would still be learned the old-fashioned way.

-

29 May 2015

at

6:03pm

Alan Benfield

says:

@

Timothy Rogers

Ah, yes, the old language lab: that was introduced into my grammar school (high school) in 1967, initially for French only, because the German teachers were old school and didn't go for it. My teacher was a guy called Carl Hermus, a French-speaking Belgian. We actually used his text-books. He used to tear his hair out at the way we mangled his language, but the lab was arguably good for those who actually listened and tried to copy what they heard.

-

5 June 2015

at

1:24pm

rustiguzzi

says:

@

David Gordon

You are not alone. I, too, learned - or at least, started to learn - German using "Heute Abend", at school in about 1969. After a term or so we stopped, something to do with the Timetable or the teacher leaving, I forget now. Fortunately for us, the edition we used had the normal alphabet and not Fraktur.

-

8 June 2015

at

8:59am

OldScrounger

says:

@

rustiguzzi

The correct title is "Heute Abend!" mysteriously suggestive of nocturnal pleasures to come. Somehow Volume One was enough to get me through O-level as a VI Form extra subject. I, too, found both volumes in second-hand shops.

-

1 June 2015

at

9:18am

flannob

says:

At a state school in Austin TX in 1963 I took German, as there was a large German- (and Czech-) descended presence in the state, reflected in town names like "New Braunfelds". In 1964-7 at a prestigious private school in Dallas we were offered Spanish, French and Russian, the latter for its convenience in accessing scientific publications. No German, rumoured to be due to the sensitivities of an English headmaster.

-

2 June 2015

at

4:13pm

bertzpoet

says:

The Hakenkreuz itself seems fractured.

-

2 June 2015

at

8:31pm

dcuprichard

says:

My mother was born in Hansestadt Kolberg on the Baltic, in what then was Hinterpommern and is now Poland. She met my father, a Scottish army captain in '45, married in Scotland in '47, where she lived the rest of her long life. She must have been one of the last generation of girls to learn "Sütterlin" handwriting. She was a great letter writer, but nobody in the family (Scottish or German) or the schools in Scotland where she taught history and German, could read her handwriting. I treasure her letters as a variety of cuneiform.

-

3 June 2015

at

12:31am

karhu

says:

Finnish has also used fraktur. I have a Marxist book from 1911 published in Hancock, Michigan (US) (Köyhäliston Nuija)in which the chapter headings are all in fraktur, though the text itself is entirely in roman.

-

3 June 2015

at

11:10am

A.J. Sutter

says:

According to one theory, the Jewish connection resulted from a sort of Freudian free association.

-

3 June 2015

at

5:58pm

Louis Mackay

says:

Thanks to A. J. Sutter for that interesting note. S H Steinberg was a distinguished historian of Germany (whence he came to Britain in 1936) as well as of typography. His classic, Five Hundred Years of Printing (1955), has some comment on the Antiqua-Fraktur dispute, including the two-mindeness of the Nazis in this respect, and records that, according to Hitler, Fraktur was "invented by a Jew called Schwabach". According to Steinberg. "Schwabacher" Black Letter first appeared in Nürnberg, Mainz and Ulm about 1480, and "certainly did not originate in the little Franconian town of Schwabach". The style now known as Fraktur was refined in the 1520s in Nürnberg, by the writing master Johann Neudörffer and the punch-cutter Hieronymous Andreae. However, says Steinberg, the terms "Schwabacher" and "Fraktur", were both "fanciful inventions of later writers".

-

3 June 2015

at

6:24pm

Philip Welch

says:

Before attending the archetypal English public school (Lancing College 1966-70) I had been given the choice of German or Ancient Greek at age 12. I chose Greek. (French had been compulsory since age 7 and Latin since 8 so no choices there.) I did not regret the choice: Lancing was as High Church as you could get without being R. Catholic, so I was obliged to take "Divinity" O-Level. I found that with the "Divinity with Greek Text" option, one could get 50% of the marks translating a chapter of St. Mark and some of the Acts, without having to regurgitate any adolescent theological remarks on various gobbits or quotes. This suited my atheist tendencies: you only had to learn "eye of a needle", "camel" etc. and you were away. The English of course was repetitively rammed down our throats on Sundays + 3 further Evensong services per week.

-

4 June 2015

at

1:02am

Timothy Rogers

says:

To the eye of non-German speakers whose languages have been printed in some version of Roman font for hundreds of years, Fraktur may strike them as cluttered. On the other, some folks have found it to be “fancy” or ornate and therefore have selected it for specific, limited uses, as in the masthead of The New York Times. Other have pointed out similar uses above, including the "Ye Olde Whatever” trope, and there is many a beer label that uses it as well. I’ve also seen it on “fancy” Christmas cards. However, besides German and some of the other German-family languages, have any other European languages used it for printing whole books?

-

28 June 2015

at

6:51pm

cizinka

says:

Old Czech bibles were regularly printed in Fraktur. It's not entirely uncommon to come across printed books from before 1918 in 'Czech Fraktur'. It looks singularly difficult to read.

Read moreAlong with wine and beer labels, and Inn signs, where the use of "Broken Script" remained uncontroversial, and certain logos and signs, including the standard German sign for a pharmacy, some limited use of Fraktur has been made in German publishing since 1945. Herman Hesse, whose works were banned by the Nazis, is said to have insisted on Fraktur for his own books. But generally there was little enthusiasm for it in postwar West Germany – no doubt because of discomfort at the nationalistic flavour it was widely perceived to have (notwithstanding Bormann's conspiracy theory), which was at odds with the Federal Republic's aspirations as a partner in a modern Europe. The attitude of occupying powers in 1945 seems to have been inconsistent. Some Allied-authorised newspaper licences are reported to have prohibited the use of "Gothic type", but the Occupation authorities also issued postage stamps in Fraktur to replace Third Reich stamps, and sometimes had notices printed in Fraktur. By contrast with West Germany, In the GDR, even in the publicity of the State, Fraktur continued to be used - along with other letter forms - without inhibition. In the reported words of Martin Z Schröder, a typographer trained in the GDR, "The ideological associations in West Germany were unfamiliar to us. We distinguished between beautiful and ugly typefaces, not between good and evil ones." – LM

Hitler’s remarks are far from surprising, given his fondness for classical and neo-classical architecture and his disparagement of historic old city centers as full of dark, dirty, gothic structures. In his “table-talk” he made fun of Himmler’s “ancient-Aryan” cult fetishes and remarked that while “our Teutonic ancestors” were primitives, the Greeks and Romans were building civilizations with majestic architecture to match, leaving monuments for the ages. Of course what impressed Hitler was the military success and organized state power of Greece and Rome.

The Jewish-typography conspiracy theory is, of course, totally without historical foundation and just one more example of Nazi zaniness in general. I have a fair number of German books published during the pre-WWI and the interwar eras, and most of them use Latin typeface, including books put out by Erich Reiss Verlag, a Jewish publishing house in Berlin (Reiss being Jewish and publishing a fair number of talented German-Jewish writers – Germans, Austrians, and Czechs); but many of the books from these two periods continued to use Fraktur. Bismarck et al. seem to have been experiencing some kind of Germanic chest-thumping combined with anxiety about the cultural attainments (even superiority) of non-German peoples and cultures. They knew little about the actual history of typefaces and calligraphic styles, which have fairly simple explanations, but ignorance never stopped anyone from expressing ill-founded opinions.

I’m glad I learned gothic typeface, because it gives me access to older printed documents, but my ability to decipher handwritten gothic script has deteriorated to the point that it’s not worth the effort.

I was required to learn German by my school, because all pupils going to university to read a science subject would need the language to read the journals because, after all, German was one of the main languages of science.

The world has changed. If you now submit an article in German to "Pflügers archiv für die gesamte physiologie" it will be rejected: it must be in English.

So my German is little use for the journals, but still very useful for real life.

When, in 1969, my family moved to South Suffolk, I found myself at a private school as a state-sponsored pupil (as were about 25% of the boys - Tory Suffolk County Council being too mean to spend money on building a grammar school in South Suffolk, the closest to my home being 30 miles away in Stowmarket). Here, again, everyone studied French but only the elite (well, theoretically the upper half of the ability range) studied Latin and either Ancient Greek (for the real elite) or German, a rather bizarre choice, imho.

The structure of the school timetables almost meant that my lack of Latin might have precluded me from continuing with German. Fortunately, by fiddling around with which classes I attended at what time, I was able to carry on to O-level.

Ironically, I later learned to speak French in Belgium and for a while (according to French French-speakers) had a Belgian accent.

Dr. Hermus would, hopefully, have been proud of me.

The book originally came out in 1938 but was revised in the Fifties, which was problably when the typeface changed. I only know these dates because, many years later, I found both volumes in a secondhand book shop and bought them, intending to resume my studies but never did (one of my many regrets in life).

So some sort of mis-match as to which scientific publications would be useful, and whether it was Nazism or Germany that had been defeated.

The curiously interpreted notion of "free speech" meant that a silent vigil against the war in Vietnam was greeted with uniformed. swastika be-decked American Nazi Party members proffering a large banner:"Death to Red Scum". There may have been some Gothic script in the accompanying racist propaganda.

On a trip to Munich about 10 years ago I happened to pick up a slim book called » Die Schwabacher « (Augsburg: MaroVerlag 2003), by typography scholar Philipp Luidl. The book points out that the reasons for associating the city of Schwabach with the typeface of that name remain very obscure. The type first appeared in the 1470s in Augsburg, and then spread to Ulm and Nuremberg. At that time, the city of Schwabach had neither any printer shop nor any type foundry. (Nor were Jews allowed to be in the book business.) Nonetheless, the city’s name stuck.

Luidl mentions the 1957 proposal of one S.H. Steinberg that Hitler was erroneously connecting the name of the typeface to that of the banker Paul (von) Schwabach (1867-1938), who was born Jewish but converted to Protestantism and was raised to the nobility in 1907. Von Schwabach succeeded Gerson von Bleichröder, Bismarck's leading banker and also a Jew, as head of the Bleichröder Bank, one of the most prominent financial institutions in early 20th Century Berlin — certainly well-known to Hitler.

According to Luidl, Bleichröder had moreover been the father-in-law of Bernhard Wolff, the Jewish owner of a liberal newspaper and the founder of WTB, one of the three major European wire services (the others being Reuters and Havas). WTB had been “Arianized” in 1934 under the supervision of Max Amann, one of Hitler’s early followers, the publisher of » Mein Kampf «, and his man for all matters press-related. Amann is mentioned in Bormann’s letter as one of those involved in the decision to abandon Schwabacher. Given that both WTB and Paul von Schwabach had deceased in the 1930s, it’s not clear why the typeface lasted until 1941, but apparently this loose tangle of Jewish names and family connections may have morphed into the “Schwabacher Judenletter.”

Steinberg attributes the greater use of Black Letter in Germany (and to some degree in Scandinavia and the Slavonic-language regions of central Europe) to the preponderance of religious over humanistic texts in the publishing of those countries in the 16th centuries. Others have pointed to the religious divisions in Germany after the Reformation as a root both of the typographic dispute, and of later nationalism. Lutherans and other Protestants went against Catholic tradition in elevating the German vernacular above Latin, and in using printing to make scripture directly accessible to the German-speaking faithful. From a Protestant viewpoint, "Roman" types might not only be associated with an incomprehensible and alien language (Latin), but might also be seen as being tainted by the equation of "Rome" with the antichrist and worldly corruption. Large areas of Germany, of course, remained strongly Roman Catholic, and not necessarily any more receptive to the dawning international spirit of Science and Enlightenment that favoured Antiqua, so there is no simple polarity to be drawn here. Perhaps the German preference for the term "Antiqua" rather than the "Roman" used by English speakers was deliberately intended to shift associations from Papal to Classical Rome.

Steinberg illustrates a mid-19th-centrury attempt to resolve the dispute – "a ridiculous attempt to fuse Fraktur and Antiqua" – a typeface called "Centralschrift" issued by the Berlin foundry of C. G. Schoppe in 1853. Steinberg calls this "the most remarkable example of typographical folly ever thought of". A glance at any online collection of fonts today would surely qualify this as an overstatement, but Centralschrift – much more Fraktur than Antiqua – is culpably overdressed in showy pseudo-medieval mannerisms.

Steinberg is openly on the side of Antiqua, but claims that, even when using Antiqua types, a book produced by German compositors and printers "simply does not look like an English, French or Italian book, but rather gives the impression of a translation that has not quite caught the spirit of the original" – owing to subtleties of leading spacing, indenting and other "first principles of typography" that they had supposedly failed to replicate. Even if that were ever true of some individual books, it was surely an unfair appraisal of German typography as a whole, even in 1955, and it might even be taken to lend weight to the notion, which Steinberg himself opposes, that a national essence can be contained in typography: " … the idea of a "national" type," he says, " ran counter to the whole development of printing as a vehicle of international understanding."

Curiously I had my arm twisted to take Russian A-Level - on the grounds other blogs have mentioned: "Scientific articles were being written in Russian". I resisted.

German speakers themselves have mixed the two different fonts together on public paper such as currency and postage stamps. I just took a look at a stamp collection of pre-1871 German states, Germany, and Austria that my father and I put together back in the 1960s. I haven’t looked at in ages, but this discussion prompted me to do just that. The large number of regular issue stamps featuring portraits of Franz Josef are in Roman typeface. But throughout the interwar years there is a division, with some commemorative issues of the Austrian Republic being in Roman, others in Fraktur. Some of the pre-unifications states (Baden, Bavaria, Wurrtemberg) used Roman, others used Fraktur. The standard Wilhelmine era regular stamp (“Germania”) uses Fraktur, while stamps issued during the Weimar Republic years use both. As did stamps put out by the Third Reich. Two iconic examples: the “Hitler head” stamps (regular issues, not special issues) used Roman font, while the “official” stamps used by various government agencies featured a swastika encircled by a wreath, with the lettering in Fraktur. There are even overprint issues where the overprint is Fraktur and the underlying stamp Roman. It seems like typographers focused on design qualities rather than some hidden content were calling the shots here.