Tintin in China

Louis Mackay

In his recent piece on Hergé in the LRB, Christopher Tayler notes the influence on Tintin’s creator of a Chinese artist, Zhang Chongren, whom he met in 1934, as he was starting work on The Blue Lotus. In the story, Tintin saves a Chinese boy called Chang Chong-Chen from a flood and the two become inseparable allies. Set in and around Shanghai in the early 1930s, the plot is loosely based on the Mukden Incident and the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. As well as scheming Japanese officers, the villains include an American businessman and a venal British police chief.

The book is sympathetic to the Chinese and, as Tayler says, ‘consciously satirical towards European notions of cultural superiority’. Zhang is generally credited with bringing about this change in Hergé’s attitudes, as well as with helping him develop a sense of pictorial composition that owes something to Chinese aesthetics. But Zhang also made a more direct contribution to The Blue Lotus.

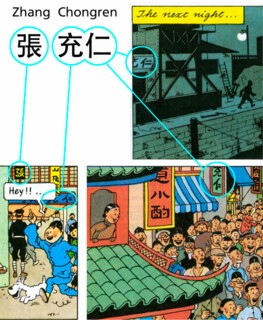

When I first read the story, I was interested by the profusion of Chinese writing in signs, wall-hangings, posters, graffiti, and occasionally speech bubbles. What did they say? Or were they merely random characters included for atmospheric effect? I later learned some Chinese, and found that they were intelligible. Some characters in the larger banners may have been copied by Hergé or a studio assistant, but the smaller texts are written with such assurance that the hand must be Zhang’s. In three places his personal name 充仁 (Chongren) appears as a cryptic signature, partly obscured, on signs in the background, once next to the character 張, Zhang, his family name.

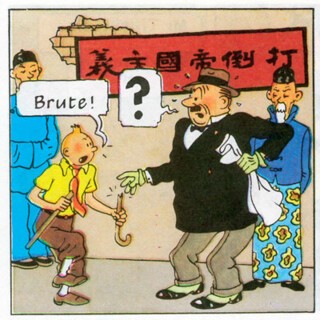

One prevalent poster is an advertisement for Siemens (西門子, ‘Xi-men-zi’), which had run factories in China since 1899. Indoors there are proverbs and shanshui poems. Political slogans aredaubed on outside walls. Some are incomplete but all would have been instantly understood by a Chinese reader. A truncated line of graffiti refers to 三民主義, the ‘Three Principles of the People’adopted by the Chinese Republic under Sun Yat-sen (national self-determination, democracy and the welfare of the people). A torn poster reads: 取消不平等... (‘Abrogate the unequal...’). Any Chinese reader would know that the final missing characters were 條約, ‘treaties’. The ‘agreements’ imposed by force after the Opium Wars, which established Western and Japanese commercial dominance in the treaty ports, with extraterritorial rights giving foreigners immunity from Chinese law, were deeply resented.

In a pivotal scene, Tintin goes to the aid of a rickshaw puller who is being beaten and abused as a ‘dirty little Chinaman’ by the villainous American businessman. A prominent poster spanning the frame carries the slogan 打倒帝國主義: ‘Smash imperialism.’

When The Blue Lotus was first published, Japan complained formally to the Belgian government. Chiang Kai-shek liked it so much, he invited Hergé to visit China. A redrawn edition was published after the war but then suppressed by the Communists. In 1984 the Beijing authorities permitted a new edition, but only after some further changes were made – not to the story, but to the Chinese background detail. Deng Xiaoping’s plans for China’s development depended on encouraging Japanese and other foreign investment. A poster that had originally said 抵制日貨 (‘Boycott Japanese goods’) became a street sign: 大吉路 (‘Great Auspiciousness Street’).

Tintin’s friend Chang reappears in Tintin in Tibet (1958), but Hergé lost touch with Zhang Chongren in the late 1930s. They finally met again in 1981. Zhang, who had become a menial labourer during the Cultural Revolution, regained his reputation as an artist in China, but spent his last years in France, where he died in 1998.

Comments

Whilst learning Chinese to decipher the inscriptions in the book is truly admirable, for those without the time or the inclination, there is a complete guide to the Chinese text on our Tintinologist.org web-site:

http://www.tintinologist.org/guides/books/05bluelotus.html