Wallace v. the Terrible Master

Alex Abramovich · David Foster Wallace

When my friends and I were young and awed by David Foster Wallace (whose papers were recently acquired by the ultra-acquisitive Harry Ransom Center) we saw the author's ever-present head scarf as a sort of tourniquet: it keeps his brains in, we thought. We were joking, of course. We didn't know how tortured he really was.

Wallace's terminal self-consciousness seemed to us to be symptomatic of the times. If anyone had the intelligence and stamina to point the way out of our post-postmodern labyrinth, it was him. And, for a while at least, Wallace seemed willing and able to shoulder the burden.

'For me, the past few years of the postmodern era have seemed a bit like the way you feel when you're in high school and your parents go on a trip, and you throw a party,' he said in 1993, in a long interview with the Review of Contemporary Fiction:

For a while it’s great, free and freeing, parental authority gone and overthrown, a cat’s-away-let’s-play Dionysian revel. But then time passes and the party gets louder and louder, and you run out of drugs, and nobody’s got any money for more drugs, and things get broken and spilled, and there’s a cigarette burn on the couch, and you’re the host and it’s your house too, and you gradually start wishing your parents would come back and restore some fucking order in your house... And of course we’re uneasy about the fact that we wish they’d come back – I mean, what’s wrong with us? Are we total pussies? Is there something about authority and limits we actually need? And then the uneasiest feeling of all, as we start gradually to realise that parents in fact aren’t ever coming back – which means 'we’re' going to have to be the parents.

It's difficult now to think about Wallace's eventual unravelling as a thing apart from his outsized ambitions. The bar was impossibly high, and his final story collection, Oblivion (2004), was especially problematic. The best stories were feverish; the weaker ones read like fuck-yous to the reader. Even the footnotes – more of a trademark than the head scarves had ever been – seemed off: not dialectical devices, but drainpipes, which barely contained the informational overflow. (Was it entirely coincidental that Wallace seemed to have given up on the head scarves?) 'Think of the old cliché about the mind being an excellent servant but a terrible master,' Wallace said a few years later:

This, like many clichés, so lame and unexciting on the surface, actually expresses a great and terrible truth. It is not the least bit coincidental that adults who commit suicide with firearms almost always shoot themselves in: the head. They shoot the terrible master.

In the event, Wallace chose another cliché for himself; nailed his belt to a patio rafter, stood on a lawn chair, and kicked. But one thing sticks in the mind: according to the autopsy report (parts of which read like passages from Wallace's books), he had bound his own wrists with duct-tape. I can't stop thinking of that detail, which seems so sadly novelistic, and so typical of Wallace's self-consciously self-complicating relationship with his own terrible master.

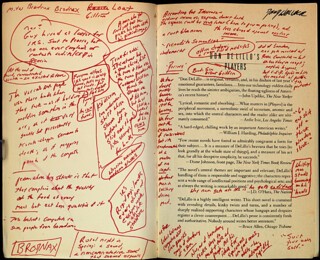

We're left with detritus: The endnotes and effluvia now at the Harry Ransom Center; the undergraduate thesis, which will be published this year; the unfinished novel due out in 2011. And two full-length biographies, forthcoming from the authors of posthumous profiles in Rolling Stone and The New Yorker. I read both profiles again this weekend: they describe a terrible struggle, but they also left me feeling simple gratitude that Wallace – who turns out to have had a history of suicide attempts, electroshock treatments, and stints in mental hospitals and rehab facilities – should have held on for so long, and have written so much.

Comments

Perhaps they present themselves with so many problems they find deplorable solutions thuis creating the genious. perhaps those who commit suicide decide they simply just, have too much to give.

Alex, your writing is delicious.